полная версия

полная версияThe Lancashire Witches: A Romance of Pendle Forest

CHAPTER VII.—THE RUINED CONVENTUAL CHURCH

Beneath a wild cherry-tree, planted by chance in the Abbey gardens, and of such remarkable size that it almost rivalled the elms and lime trees surrounding it, and when in bloom resembled an enormous garland, stood two young maidens, both of rare beauty, though in totally different styles;—the one being fair-haired and blue-eyed, with a snowy skin tinged with delicate bloom, like that of roses seen through milk, to borrow a simile from old Anacreon; while the other far eclipsed her in the brilliancy of her complexion, the dark splendour of her eyes, and the luxuriance of her jetty tresses, which, unbound and knotted with ribands, flowed down almost to the ground. In age, there was little disparity between them, though perhaps the dark-haired girl might be a year nearer twenty than the other, and somewhat more of seriousness, though not much, sat upon her lovely countenance than on the other's laughing features. Different were they too, in degree, and here social position was infinitely in favour of the fairer girl, but no one would have judged it so if not previously acquainted with their history. Indeed, it was rather the one having least title to be proud (if any one has such title) who now seemed to look up to her companion with mingled admiration and regard; the latter being enthralled at the moment by the rich notes of a thrush poured from a neighbouring lime-tree.

Pleasant was the garden where the two girls stood, shaded by great trees, laid out in exquisite parterres, with knots and figures, quaint flower-beds, shorn trees and hedges, covered alleys and arbours, terraces and mounds, in the taste of the time, and above all an admirably kept bowling-green. It was bounded on the one hand by the ruined chapter-house and vestry of the old monastic structure, and on the other by the stately pile of buildings formerly making part of the Abbot's lodging, in which the long gallery was situated, some of its windows looking upon the bowling-green, and then kept in excellent condition, but now roofless and desolate. Behind them, on the right, half hidden by trees, lay the desecrated and despoiled conventual church. Reared at such cost, and with so much magnificence, by thirteen abbots—the great work having been commenced, as heretofore stated, by Robert de Topcliffe, in 1330, and only completed in all its details by John Paslew; this splendid structure, surpassing, according to Whitaker, "many cathedrals in extent," was now abandoned to the slow ravages of decay. Would it had never encountered worse enemy! But some half century later, the hand of man was called in to accelerate its destruction, and it was then almost entirely rased to the ground. At the period in question though partially unroofed, and with some of the walls destroyed, it was still beautiful and picturesque—more picturesque, indeed than in the days of its pride and splendour. The tower with its lofty crocketed spire was still standing, though the latter was cracked and tottering, and the jackdaws roosted within its windows and belfry. Two ranges of broken columns told of the bygone glories of the aisles; and the beautiful side chapels having escaped injury better than other parts of the fabric, remained in tolerable preservation. But the choir and high altar were stripped of all their rich carving and ornaments, and the rain descended through the open rood-loft upon the now grass-grown graves of the abbots in the presbytery. Here and there the ramified mullions still retained their wealth of painted glass, and the grand eastern window shone gorgeously as of yore. All else was neglect and ruin. Briers and turf usurped the place of the marble pavement; many of the pillars were festooned with ivy; and, in some places, the shattered walls were covered with creepers, and trees had taken root in the crevices of the masonry. Beautiful at all times were these magnificent ruins; but never so beautiful as when seen by the witching light of the moon—the hour, according to the best authority, when all ruins should be viewed—when the long lines of broken pillars, the mouldering arches, and the still glowing panes over the altar, had a magical effect.

In front of the maidens stood a square tower, part of the defences of the religious establishment, erected by Abbot Lyndelay, in the reign of Edward III., but disused and decaying. It was sustained by high and richly groined arches, crossing the swift mill-race, and faced the river. A path led through the ruined chapter-house to the spacious cloister quadrangle, once used as a cemetery for the monks, but now converted into a kitchen garden, its broad area being planted out, and fruit-trees trained against the hoary walls. Little of the old refectory was left, except the dilapidated stairs once conducting to the gallery where the brethren were wont to take their meals, but the inner wall still served to enclose the garden on that side. Of the dormitory, formerly constituting the eastern angle of the cloisters, the shell was still left, and it was used partly as a grange, partly as a shed for cattle, the farm-yard and tenements lying on this side.

Thus it will be seen that the garden and grounds, filling up the ruins of Whalley Abbey, offered abundant points of picturesque attraction, all of which—with the exception of the ruined conventual church—had been visited by the two girls. They had tracked the labyrinths of passages, scaled the broken staircases, crept into the roofless and neglected chambers, peered timorously into the black and yawning vaults, and now, having finished their investigations, had paused for awhile, previous to extending their ramble to the church, beneath the wild cherry-tree to listen to the warbling of the birds.

"You should hear the nightingales at Middleton, Alizon," observed Dorothy Assheton, breaking silence; "they sing even more exquisitely than yon thrush. You must come and see me. I should like to show you the old house and gardens, though they are very different from these, and we have no ancient monastic ruins to ornament them. Still, they are very beautiful; and, as I find you are fond of flowers, I will show you some I have reared myself, for I am something of a gardener, Alizon. Promise you will come."

"I wish I dared promise it," replied Alizon.

"And why not, then?" cried Dorothy. "What should prevent you? Do you know, Alizon, what I should like better than all? You are so amiable, and so good, and so—so very pretty; nay, don't blush—there is no one by to hear me—you are so charming altogether, that I should like you to come and live with me. You shall be my handmaiden if you will."

"I should desire nothing better, sweet young lady," replied Alizon; "but—"

"But what?" cried Dorothy. "You have only your own consent to obtain."

"Alas! I have," replied Alizon.

"How can that be!" cried Dorothy, with a disappointed look. "It is not likely your mother will stand in the way of your advancement, and you have not, I suppose, any other tie? Nay, forgive me if I appear too inquisitive. My curiosity only proceeds from the interest I take in you."

"I know it—I feel it, dear, kind young lady," replied Alizon, with the colour again mounting her cheeks. "I have no tie in the world except my family. But I am persuaded my mother will never allow me to quit her, however great the advantage might be to me."

"Well, though sorry, I am scarcely surprised at it," said Dorothy. "She must love you too dearly to part with you."

"I wish I could think so," sighed Alizon. "Proud of me in some sort, though with little reason, she may be, but love me, most assuredly, she does not. Nay more, I am persuaded she would be glad to be freed from my presence, which is an evident restraint and annoyance to her, were it not for some motive stronger than natural affection that binds her to me."

"Now, in good sooth, you amaze me, Alizon!" cried Dorothy. "What possible motive can it be, if not of affection?"

"Of interest, I think," replied Alizon. "I speak to you without reserve, dear young lady, for the sympathy you have shown me deserves and demands confidence on my part, and there are none with whom I can freely converse, so that every emotion has been locked up in my own bosom. My mother fancies I shall one day be of use to her, and therefore keeps me with her. Hints to this effect she has thrown out, when indulging in the uncontrollable fits of passion to which she is liable. And yet I have no just reason to complain; for though she has shown me little maternal tenderness, and repelled all exhibition of affection on my part, she has treated me very differently from her other children, and with much greater consideration. I can make slight boast of education, but the best the village could afford has been given me; and I have derived much religious culture from good Doctor Ormerod. The kind ladies of the vicarage proposed, as you have done, that I should live with them, but my mother forbade it; enjoining me, on the peril of incurring her displeasure, not to leave her, and reminding me of all the benefits I have received from her, and of the necessity of making an adequate return. And, ungrateful indeed I should be, if I did not comply; for, though her manner is harsh and cold to me, she has never ill-used me, as she has done her favourite child, my little sister Jennet, but has always allowed me a separate chamber, where I can retire when I please, to read, or meditate, or pray. For, alas! dear young lady, I dare not pray before my mother. Be not shocked at what I tell you, but I cannot hide it. My poor mother denies herself the consolation of religion—never addresses herself to Heaven in prayer—never opens the book of Life and Truth—never enters church. In her own mistaken way she has brought up poor little Jennet, who has been taught to make a scoff at religious truths and ordinances, and has never been suffered to keep holy the Sabbath-day. Happy and thankful am I, that no such evil lessons have been taught me, but rather, that I have profited by the sad example. In my own secret chamber I have prayed, daily and nightly, for both—prayed that their hearts might be turned. Often have I besought my mother to let me take Jennet to church, but she never would consent. And in that poor misguided child, dear young lady, there is a strange mixture of good and ill. Afflicted with personal deformity, and delicate in health, the mind perhaps sympathising with the body, she is wayward and uncertain in temper, but sensitive and keenly alive to kindness, and with a shrewdness beyond her years. At the risk of offending my mother, for I felt confident I was acting rightly, I have endeavoured to instil religious principles into her heart, and to inspire her with a love of truth. Sometimes she has listened to me; and I have observed strange struggles in her nature, as if the good were obtaining mastery of the evil principle, and I have striven the more to convince her, and win her over, but never with entire success, for my efforts have been overcome by pernicious counsels, and sceptical sneers. Oh, dear young lady, what would I not do to be the instrument of her salvation!"

"You pain me much by this relation, Alizon," said Dorothy Assheton, who had listened with profound attention, "and I now wish more ardently than ever to take you from such a family."

"I cannot leave them, dear young lady," replied Alizon; "for I feel I may be of infinite service—especially to Jennet—by staying with them. Where there is a soul to be saved, especially the soul of one dear as a sister, no sacrifice can be too great to make—no price too heavy to pay. By the blessing of Heaven I hope to save her! And that is the great tie that binds me to a home, only so in name."

"I will not oppose your virtuous intentions, dear Alizon," replied Dorothy; "but I must now mention a circumstance in connexion with your mother, of which you are perhaps in ignorance, but which it is right you should know, and therefore no false delicacy on my part shall restrain me from mentioning it. Your grandmother, Old Demdike, is in very ill depute in Pendle, and is stigmatised by the common folk, and even by others, as a witch. Your mother, too, shares in the opprobrium attaching to her."

"I dreaded this," replied Alizon, turning deadly pale, and trembling violently, "I feared you had heard the terrible report. But oh, believe it not! My poor mother is erring enough, but she is not so bad as that. Oh, believe it not!"

"I will not believe it," said Dorothy, "since she is blessed with such a daughter as you. But what I fear is that you—you so kind, so good, so beautiful—may come under the same ban."

"I must run this risk also, in the good work I have appointed myself," replied Alizon. "If I am ill thought of by men, I shall have the approval of my own conscience to uphold me. Whatever betide, and whatever be said, do not you think ill of me, dear young lady."

"Fear it not," returned Dorothy, earnestly.

While thus conversing, they gradually strayed away from the cherry-tree, and taking a winding path leading in that direction, entered the conventual church, about the middle of the south aisle. After gazing with wonder and delight at the still majestic pillars, that, like ghosts of the departed brethren, seemed to protest against the desolation around them, they took their way along the nave, through broken arches, and over prostrate fragments of stone, to the eastern extremity of the fane, and having admired the light shafts and clerestory windows of the choir, as well as the magnificent painted glass over the altar, they stopped before an arched doorway on the right, with two Gothic niches, in one of which was a small stone statue of Saint Agnes with her lamb, and in the other a similar representation of Saint Margaret, crowned, and piercing the dragon with a cross. Both were sculptures of much merit, and it was wonderful they had escaped destruction. The door was closed, but it easily opened when tried by Dorothy, and they found themselves in a small but beautiful chapel. What struck them chiefly in it was a magnificent monument of white marble, enriched with numerous small shields, painted and gilt, supporting two recumbent figures, representing Henry de Lacy, one of the founders of the Abbey, and his consort. The knight was cased in plate armour, covered with a surcoat, emblazoned with his arms, and his feet resting upon a hound. This superb monument was wholly uninjured, the painting and gilding being still fresh and bright. Behind it a flag had been removed, discovering a flight of steep stone steps, leading to a vault, or other subterranean chamber.

After looking round this chapel, Dorothy remarked, "There is something else that has just occurred to me. When a child, a strange dark tale was told me, to the effect that the last ill-fated Abbot of Whalley laid his dying curse upon your grandmother, then an infant, predicting that she should be a witch, and the mother of witches."

"I have heard the dread tradition, too," rejoined Alizon; "but I cannot, will not, believe it. An all-benign Power will never sanction such terrible imprecations."

"Far be it from me to affirm the contrary," replied Dorothy; "but it is undoubted that some families have been, and are, under the influence of an inevitable fatality. In one respect, connected also with the same unfortunate prelate, I might instance our own family. Abbot Paslew is said to be unlucky to us even in his grave. If such a curse, as I have described, hangs over the head of your family, all your efforts to remove it will be ineffectual."

"I trust not," said Alizon. "Oh! dear young lady, you have now penetrated the secret of my heart. The mystery of my life is laid open to you. Disguise it as I may, I cannot but believe my mother to be under some baneful influence. Her unholy life, her strange actions, all impress me with the idea. And there is the same tendency in Jennet."

"You have a brother, have you not?" inquired Dorothy.

"I have," returned Alizon, slightly colouring; "but I see little of him, for he lives near my grandmother, in Pendle Forest, and always avoids me in his rare visits here. You will think it strange when I tell you I have never beheld my grandmother Demdike."

"I am glad to hear it," exclaimed Dorothy.

"I have never even been to Pendle," pursued Alizon, "though Jennet and my mother go there frequently. At one time I much wished to see my aged relative, and pressed my mother to take me with her; but she refused, and now I have no desire to go."

"Strange!" exclaimed Dorothy. "Every thing you tell me strengthens the idea I conceived, the moment I saw you, and which my brother also entertained, that you are not the daughter of Elizabeth Device."

"Did your brother think this?" cried Alizon, eagerly. But she immediately cast down her eyes.

"He did," replied Dorothy, not noticing her confusion. "'It is impossible,' he said, 'that that lovely girl can be sprung from'—but I will not wound you by adding the rest."

"I cannot disown my kindred," said Alizon. "Still, I must confess that some notions of the sort have crossed me, arising, probably, from my mother's extraordinary treatment, and from many other circumstances, which, though trifling in themselves, were not without weight in leading me to the conclusion. Hitherto I have treated it only as a passing fancy, but if you and Master Richard Assheton"—and her voice slightly faltered as she pronounced the name—"think so, it may warrant me in more seriously considering the matter."

"Do consider it most seriously, dear Alizon," cried Dorothy. "I have made up my mind, and Richard has made up his mind, too, that you are not Mother Demdike's grand-daughter, nor Elizabeth Device's daughter, nor Jennet's sister—nor any relation of theirs. We are sure of it, and we will have you of our mind."

The fair and animated speaker could not help noticing the blushes that mantled Alizon's cheeks as she spoke, but she attributed them to other than the true cause. Nor did she mend the matter as she proceeded.

"I am sure you are well born, Alizon," she said, "and so it will be found in the end. And Richard thinks so, too, for he said so to me; and Richard is my oracle, Alizon."

In spite of herself Alizon's eyes sparkled with pleasure; but she speedily checked the emotion.

"I must not indulge the dream," she said, with a sigh.

"Why not?" cried Dorothy. "I will have strict inquiries made as to your history."

"I cannot consent to it," replied Alizon. "I cannot leave one who, if she be not my parent, has stood to me in that relation. Neither can I have her brought into trouble on my account. What will she think of me, if she learns I have indulged such a notion? She will say, and with truth, that I am the most ungrateful of human beings, as well as the most unnatural of children. No, dear young lady, it must not be. These fancies are brilliant, but fallacious, and, like bubbles, burst as soon as formed."

"I admire your sentiments, though I do not admit the justice of your reasoning," rejoined Dorothy. "It is not on your own account merely, though that is much, that the secret of your birth—if there be one—ought to be cleared up; but, for the sake of those with whom you may be connected. There may be a mother, like mine, weeping for you as lost—a brother, like Richard, mourning you as dead. Think of the sad hearts your restoration will make joyful. As to Elizabeth Device, no consideration should be shown her. If she has stolen you from your parents, as I suspect, she deserves no pity."

"All this is mere surmise, dear young lady," replied Alizon.

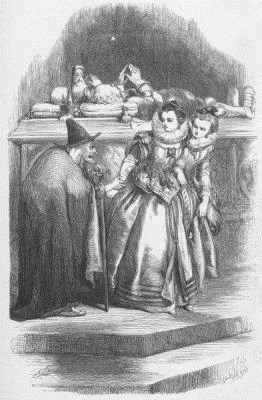

At this juncture they were startled, by seeing an old woman come from behind the monument and plant herself before them. Both uttered a cry, and would have fled, but a gesture from the crone detained them. Very old was she, and of strange and sinister aspect, almost blind, bent double, with frosted brows and chin, and shaking with palsy.

"Stay where you are," cried the hag, in an imperious tone. "I want to speak to you. Come nearer to me, my pretty wheans; nearer—nearer."

And as they complied, drawn towards her by an impulse they could not resist, the old woman caught hold of Alizon's arm, and said with a chuckle. "So you are the wench they call Alizon Device, eh!"

"Ay," replied Alizon, trembling like a dove in the talons of a hawk.

"Do you know who I am?" cried the hag, grasping her yet more tightly. "Do you know who I am, I say? If not, I will tell you. I am Mother Chattox of Pendle Forest, the rival of Mother Demdike, and the enemy of all her accursed brood. Now, do you know me, wench? Men call me witch. Whether I am so or not, I have some power, as they and you shall find. Mother Demdike has often defied me—often injured me, but I will have my revenge upon her—ha! ha!"

"Let me go," cried Alizon, greatly terrified.

"I will run and bring assistance," cried Dorothy. And she flew to the door, but it resisted her attempts to open it.

"Come back," screamed the hag. "You strive in vain. The door is fast shut—fast shut. Come back, I say. Who are you?" she added, as the maid drew near, ready to sink with terror. "Your voice is an Assheton's voice. I know you now. You are Dorothy Assheton—whey-skinned, blue-eyed Dorothy. Listen to me, Dorothy. I owe your family a grudge, and, if you provoke me, I will pay it off in part on you. Stir not, as you value your life."

The poor girl did not dare to move, and Alizon remained as if fascinated by the terrible old woman.

"I will tell you what has happened, Dorothy," pursued Mother Chattox. "I came hither to Whalley on business of my own; meddling with no one; harming no one. Tread upon the adder and it will bite; and, when molested, I bite like the adder. Your cousin, Nick Assheton, came in my way, called me 'witch,' and menaced me. I cursed him—ha! ha! And then your brother, Richard—"

Mother Chattox, Alizon, and Dorothy.

"What of him, in Heaven's name?" almost shrieked Alizon.

"How's this?" exclaimed Mother Chattox, placing her hand on the beating heart of the girl.

"What of Richard Assheton?" repeated Alizon.

"You love him, I feel you do, wench," cried the old crone with fierce exultation.

"Release me, wicked woman," cried Alizon.

"Wicked, am I? ha! ha!" rejoined Mother Chattox, chuckling maliciously, "because, forsooth, I read thy heart, and betray its secrets. Wicked, eh! I tell thee wench again, Richard Assheton is lord and master here. Every pulse in thy bosom beats for him—for him alone. But beware of his love. Beware of it, I say. It shall bring thee ruin and despair."

"For pity's sake, release me," implored Alizon.

"Not yet," replied the inexorable old woman, "not yet. My tale is not half told. My curse fell on Richard's head, as it did on Nicholas's. And then the hell-hounds thought to catch me; but they were at fault. I tricked them nicely—ha! ha! However, they took my Nance—my pretty Nance—they seized her, bound her, bore her to the Calder—and there swam her. Curses light on them all!—all!—but chief on him who did it!"

"Who was he?" inquired Alizon, tremblingly.

"Jem Device," replied the old woman—"it was he who bound her—he who plunged her in the river, he who swam her. But I will pinch and plague him for it, I will strew his couch with nettles, and all wholesome food shall be poison to him. His blood shall be as water, and his flesh shrink from his bones. He shall waste away slowly—slowly—slowly—till he drops like a skeleton into the grave ready digged for him. All connected with him shall feel my fury. I would kill thee now, if thou wert aught of his."

"Aught of his! What mean you, old woman?" demanded Alizon.

"Why, this," rejoined Mother Chattox, "and let the knowledge work in thee, to the confusion of Bess Device. Thou art not her daughter."

"It is as I thought," cried Dorothy Assheton, roused by the intelligence from her terror.

"I tell thee not this secret to pleasure thee," continued Mother Chattox, "but to confound Elizabeth Device. I have no other motive. She hath provoked my vengeance, and she shall feel it. Thou art not her child, I say. The secret of thy birth is known to me, but the time is not yet come for its disclosure. It shall out, one day, to the confusion of those who offend me. When thou goest home tell thy reputed mother what I have said, and mark how she takes the information. Ha! who comes here?"