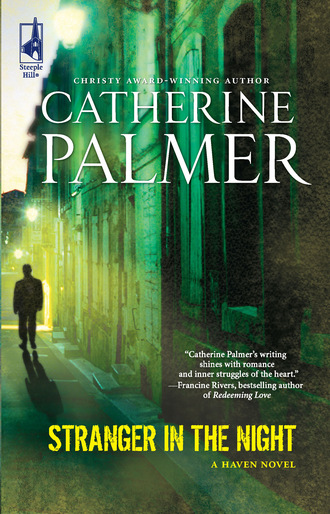

Полная версия

Stranger In The Night

“You told me you live in Texas,” she said.

“Texas can wait. I’ll stick around here for a while.” He set his large palm on Virtue’s round head. “We’ll go to the airport with you and meet family number twenty-four. You can explain your system to me on the way.”

Liz bent her head and rubbed her eyes. This was absolutely not the way her morning should go. She had files to sort. Forms to fill out. A plane to meet. Clothing and food to deliver. A refugee patient to visit in the hospital. She did not need a U. S. Marine and four Pagandans following her around like a flock of lost sheep.

Unable to bring herself to speak, she held up her hand. Instantly, Joshua’s fingers closed around hers. As she lifted her head, he tucked her hand under his arm, splaying her fingers against his biceps.

“I don’t want to hear your favorite word, Liz,” he murmured, leaning close. “ No isn’t good. Yes is much better. Say yes to the Rudi family, Liz. If you say it, I will, too. And then we’ll make a difference together.”

Everything inside Liz begged to differ. But how could she keep arguing? The man refused to hear any of her very plausible reasons why his scenario wouldn’t work.

“Fine,” she said, pulling her hand from the warm crook of his elbow. “Step one. Take the Rudi family back where you found them. Make sure they have a decent place to live with running water, flushing toilets and enough beds. Drive them to the grocery store and buy a week’s supply of staples and a few perishables. Then go to a thrift shop and see if you can find several outfits for each person. And look for coats. Winter’s coming.”

She picked up a couple of business cards and handed one to Joshua and the other to Pastor Stephen. “Here’s my number. Call me if you need me.”

Before either man could protest, Liz pushed past Joshua and headed for Molly’s cubicle, leaving the five wayfarers standing inside her own. If this was going to be a good day, she needed fortification. Her best friend would be happy to accompany her to the coffee shop down the street for a couple of lattes.

A few hours later, Joshua pulled his Cadillac into a parking space in front of the large brick edifice and switched off the engine. He knew he shouldn’t do this. If he were at all smart, right this moment he’d be on his way back to Amarillo. After a couple of easy days on the road, he would drive out to the ranch. As a matter of fact, nothing would feel better than to strip off his jeans and T-shirt, dive into the Texas-shaped pool and swim a few laps.

No doubt Magdalena would put on the dog for him—enchiladas, chile rellenos, carne adovada, homemade tortillas and a big serving of flan for dessert. The cook had been with the Duff family for years, almost a second mother to Joshua and his four brothers. During each of his deployments, she faithfully e-mailed him once a week to let him know the menu of every meal he had missed. Exquisite torture.

After Magdalena’s home-cooked dinner, he would sleep well in his big, clean, nonsandy bed. Then the following day…

As always, Joshua’s thoughts came to a screeching halt at the idea of driving into town and stepping into the Duff-Flannigan Oil building. He could almost hear his boots squeaking down the long waxed hallway. His voice would echo as he greeted his father. The large corner office would still be waiting—as it had all these years.

Business. The oil business. That’s what we do, son. It’s a Duff thing. Your daddy did it. Your grandpas did it—both sides. And your great-grandpas. That’s why we sent you off to college to get that petroleum engineering degree. You’d be doing it right now if 9/11 hadn’t happened and made you want to serve your country. We’re proud that you did, but now it’s time to take your place here. Your big brother will be CEO one day. You’re our president of field operations. Duff-Flannigan Oil is counting on you.

Hadn’t Joshua just been fighting a war some said was based on a gluttonous thirst for foreign oil? Or had it been about terrorists and the need to quash insurgent cells? Was it about politics—or changing people’s lives for the better? Things could get confusing up in the high arid desert of Afghanistan.

There.

The object of Joshua’s latest quest pushed open the door of Refugee Hope and stepped out onto the sidewalk. At the sight of Ms. Liz Wallace, something slid right down his spine and settled into the base of his stomach. And this was why he should be headed for Texas.

Sam was right about his friend. Joshua had been too long without a woman. He needed to get home, find a couple of pretty gals, and…

What? He hardly knew how to go on an old-fashioned date anymore. Did people even do that these days?

He was thirty. Thirty and battle weary. And Liz Wallace looked so good he had almost dropped to his knees the moment he laid eyes on her.

Instead, he had bullied his way into her office and annoyed her to the point that she ran him off. Worse, he had hog-tied himself to the Rudi family. Not only did he feel obligated to help the dignified Reverend Stephen and his traumatized little wife, but Joshua was positively smitten with Charity and Virtue.

Sighing, he unlatched his door and pushed it open. Liz glanced his way. Her face…for an unguarded moment…said exactly what he needed to know. She had felt it, too. That something. A palpable pull. The irresistible beckoning toward what was probably a huge mistake.

“Liz.” He called her name as she approached on the sidewalk. “Thought you’d take me up on my offer to drive you to the airport. Get a little more information from you about how to manage my new best friends.”

She swallowed. Her brown eyes went depthless for a moment as she met his gaze. Then she focused on his car. “Too small. I’m bringing back a family of five. Thanks, but I always take the agency van to the airport.”

“Good. Where’s it parked?”

“Listen, I appreciate your interest in refugees, Sergeant.”

“Joshua.”

“I don’t need your help picking up this family, and I can’t take the time to explain our system to you right now. It’s very complicated. I have a lot on my mind.”

“I’ll drive while you think.” He imitated her frown. “You’re not going to use your favorite word again are you, Liz?”

Letting out a breath, she shrugged. “Oh, come on, then. But I’ll do the driving. Agency policy.”

“You sure? You look tired.”

“Thanks.”

“Beautiful but tired.”

At the expression of surprise on her face, Joshua mentally chastised himself. Bad form, Duff. You don’t tell a woman she’s beautiful right off the bat.

On the other hand, Liz Wallace was gorgeous. Slim and not too tall, she had the sort of understated figure he liked. Nothing demure about that hair, though. Big, glossy brown curls crowned her head, settled onto her shoulders and trickled down her back. Her skin was pale, almost milky. Those melted-chocolate eyes stirred something deep inside him. But it was her lips that drew his focus every time she spoke.

“We have twenty minutes to make it to the airport.” She pushed back her hair as they approached a mammoth white van sprinkled with rust spots. “When we get there, we’ll be going to the area where international flights arrive.”

“Been through those gates a few times myself.” He smiled as yet another look of surprise crossed Liz’s face.

“I’ve seen the Army grunts at Lambert,” she said. “In and out of Fort Leonard Wood for basic training. I didn’t think the Marine Corps used the airport.”

“You might be surprised at what Marines do.”

She opened the van’s door and with some effort clambered into the driver’s seat. Joshua had all he could do to keep from picking her up and depositing her in place. But he knew better than to manhandle Liz Wallace. She might be small and delicate, but the woman had a razor-sharp streak he didn’t want to mess around with.

“I’ve flown out of Lambert, too,” she said as Joshua settled into the passenger’s seat. Starting the engine, she added, “I left the international area on my way to the DRC.”

At that, she glanced his way. The slightest smirk tilted those sumptuous lips. Clearly this was a test she hoped he would fail. A little global one-upmanship.

He fastened his seat belt and tried to relax. It wasn’t easy. Liz had on a khaki skirt that had seemed more than modest in the agency building. But in the van, it formed to the curve of her hip and revealed just enough leg to mesmerize him. He slipped his sunglasses from his pocket and put them on.

Concentrate on the conversation, Duff.

“So, did you land in Kinshasa?” he asked. “Or maybe you were headed for the eastern part of the country. A lot of people fly into Kampala and travel across the border from there, don’t they?”

She laughed easily. “Okay, you’ve been around. My group landed in Kinshasa. Have you ever visited Congo?”

“You mean the DRC?” He returned her smirk. “Nah. North Africa mostly. How’d you like it?”

“Interesting. It changed me. I’m planning to spend the rest of my life working with refugees in Africa.”

“Africa?” He frowned at the thought of settlements plagued with disease, hunger, violence. “You’re doing a good thing right here, Liz.”

“The people who make it to St. Louis are the lucky ones. All I do is mop up. Try to repair what’s already been broken. I’d prefer to go into the UN camps where I can really make a difference.”

“You’re making a difference now.”

The brown eyes slid his way for an instant. “How do you know?”

“I saw what you do.”

“Not what I want to do. My job is too much about lists and quotas. It’s all red tape and documents and files.”

“It’s people.”

“It was once. In the beginning, I thought I was really helping. But there are so many people, and the needs are overwhelming. I don’t speak anyone’s language well enough to communicate the important things I want to say.”

“What is it you want to say?”

Again she glanced at him. “Were you an interrogator?”

“Tracker.” That left out a lot, but he didn’t want to drag his military service into the open. “I did a little interviewing.”

She nodded, her attention on the traffic again. “What I want to say is…meaningful things. But I can’t. My Swahili is horrible. I’m doing well to meet my refugees’ basic needs. I don’t have time to follow through with schools to make sure the kids are adjusting. I can’t teach the mothers how to provide good nutrition. Most don’t know the simplest things about life here.”

“Like what?”

“That eggs and milk go in the refrigerator. How to use hangers in a closet. Where to put a lamp. How to microwave popcorn or make brownies from a mix. What to do with credit card offers that pour in through the mail. A lot of them don’t realize children need to wear shoes in America. Especially in the winter. But it goes beyond that.”

Joshua held his breath as she swung the van into four-lane traffic. Interstate 70 at midmorning was a free-flowing river of passenger cars and 18-wheelers. The van nestled in behind a semi, then darted out to take a spot vacated by a cab. Liz drove as he did, fearlessly. Maybe recklessly.

“I don’t know the subtext,” she was saying. “So many people groups come through Refugee Hope, and I’ve only learned a few things. Each culture is different. If I were to ask about your family in Texas, you’d give me the names of your closest relatives, right?”

“Maybe.”

“Of course you would. But a Somali would recite twenty generations back to the name of his clan father. In Somalia, men and women don’t touch each other in greeting. Elders—even total strangers—are addressed as aunt or uncle. And babies aren’t diapered. Now, that’s been interesting in St. Louis.”

“I’ll bet.”

“The Burmese—people from Myanmar—have complicated customs that involve naming a baby by the day of the week he’s born on, and his age and gender. And the name changes according to who’s talking to them. In Somalia, it’s polite to give gifts to a mother before her baby is born, like in the U. S. But you’d never do that in Burma. It would bring misfortune on the child. And you don’t give scissors or knives or anything black—to anyone. Trust and honesty are important to the Burmese. Inconsistency and vagueness are considered good manners in Somalia. It’s a positive thing to be crafty, even sly and devious.”

“The tip of the cultural iceberg.”

“A society’s rules are subtle. You were where? Afghanistan? I’m sure you learned their ways.”

“Oh, yeah.” He leaned back in the seat and verbally checked off some of the idiosyncrasies he’d been taught. “The people may seem to be standing too close, but don’t step back. It’s their way. Men walk arm in arm or hold hands—it means they’re friends and nothing more. Never point with one finger. Greet male friends with a handshake and a pat on the back. Belch in appreciation of a good meal. Never drink alcohol or eat pork in front of an Afghan. Don’t wink, blow your nose in public, eat with your left hand or sit with the soles of your feet showing.”

“Well done, Sergeant Duff,” she said. “Then you know that until you begin to understand people, you can’t help them much.”

“And you’re all about helping.”

She pulled the van into a space in the short-term parking area at Lambert. “So are you, Sergeant. We’ve just chosen different ways to go about it.”

Before he could unbuckle his seat belt, Liz hopped out of the van and started for the terminal. Joshua had never considered tracking insurgents a mercy mission. He was a huntsman. A sniper. A warrior who set out on a mission and didn’t stop until he’d accomplished it.

Watching Liz stride purposefully through the sliding-glass door, Joshua realized she might be right about him. Maybe they had more in common than he knew.

Chapter Three

L iz sat at her desk, staring. The stack of files blurred as her eyes lost focus. The sounds of people talking in cubicles nearby faded. Unnoticed, the hand on the clock ticked toward five. Even the candy bar in her desk drawer ceased its demand, its chocolate-caramel siren song ebbing.

“Wakey-wakey, Sleeping Beauty!” Molly breezed into the cubicle. “Time for your happy news report from the Fairy Godmother.”

Settling on the edge of a chair, her favorite perch, the reed-thin woman waved a sheaf of stapled pages. Molly’s exuberance and generally cheerful outlook belied the fact that she had battled an eating disorder most of her adult life. Only Liz knew, and the two made it a matter of prayer each evening before they left the office.

“More trouble in Africa,” Molly began, reading from their weekly headquarters update. “Sudanese refugees are still flooding south. Tribal tension continues to flare in Eastern and Central Africa. The Kenyan camps are full to overflowing. Really? Surprise me some more. Congo and Burundi are still unstable. Rwanda isn’t much better. And on to Asia! Hostility has increased toward the Karen people group in Burma/Myanmar. Refugees are heading for Thailand in record numbers. People are still fleeing Vietnam and North Korea. Yeah—when they can get out. Europe is pretty quiet, but the Middle East is tumultuous. This could’ve been last week’s report.”

Liz had closed her eyes and was trying to pull out any important information between Molly’s running commentary. Sarcasm bordering on outright derision was the woman’s stock in trade.

“Now for our weekly federal government refugee resettlement averages,” Molly continued. “Currently in St. Louis there are 2,500 Somalis, more than 1,000 Ethiopians, 700 from ex-Soviet states, 700 Liberians, 500 Sudanese, 300 each from Bosnia, Vietnam, Iran and Afghanistan. The Turks and Burmese are passing the 100 mark, and Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, Burundi and Eritrea are catching up fast.”

“Just give me next week’s airport list, Molly.” Liz held out a hand. “I can’t process this stuff right now.”

“What’s going on? Have you been staying awake all night again—plotting your own refugee flight into darkest Africa?”

“No, it’s not that. I’ve had a hard day.”

“The Marine.”

Liz looked up. “You remember him?”

“Who could forget? Every woman in the building—married and single—watched you drive off with the guy this morning, Liz. I’d have been in here sooner but I had to pick up some sardines and Spam to welcome my latest batch of Burmese.”

They laughed together at these favorite foods of the silent, polite and terribly modest people group. It was hard to know what would strike the fancy of a given batch of refugees. A few local stores had started carrying live bullfrogs and eels, packaged duck heads and various other items too pungent even for Liz—who considered herself brave compared to many in the agency.

Molly set her elbows on Liz’s desk and rested her chin on her palms. “What’s his name, where’s he from and how long do you get to keep him?”

“I don’t want him.” Liz let out a low growl. “Men like that should not exist. They complicate everything.”

“But they’re oh, so nice to look at.”

“I can’t argue there. You could drown in his eyes. Seriously, though, this guy is a pain. Very demanding. When he’s not chasing insurgents in Afghanistan, he lives in Texas. He’s visiting a friend here, and somehow he got tangled up with a family of Pagandans.”

“Ooh. Paganda is not a nice place.”

“No, and Joshua’s people have been through the wringer. Global Care brought them in from Kenya, but they’re on their own now. Except for Sergeant Duff, USMC. Their story won him over. The two children hid inside a metal drum while rebels massacred their mother and siblings. Their house burned down around them, but they survived.”

“Wow.” Molly fell silent—for once.

“Joshua met these people last night, and now he’s determined to help them through the entire resettlement process. I told him that was crazy. It’s too complicated and time-consuming for one person, but he wouldn’t budge.”

“Is he aware of the cost? Without an agency supporting the family, that could get expensive.”

Liz paused, weighing whether to tell Molly what she had learned about Joshua’s family. Finally, she spoke. “Okay, the guy is filthy rich.”

“Mmm. Even better. Let’s see. Joshua is rich. Joshua is handsome. Joshua is tenderhearted toward the poor and needy. What’s not to like about Joshua?”

“He doesn’t take no for an answer, he’s domineering, he’s forceful, he’s way too self-assured and…and…” Liz clenched her fists. “I don’t want to like him, Molly!”

“Why not?”

“Because I’m going to Africa. As soon as I become fluent in Swahili and get enough experience for the UN to want to hire me, I’m out of here. I don’t have time for complications. I can’t let myself think about Joshua Duff, and I hope I never see him again.”

Liz shook her head. “No, that’s not true. I can’t think about anything else, and it’s driving me nuts. You know what I went through with Taylor. It took me forever to figure out how wrong we were.”

“I could have told you in two seconds.”

“And you did.”

“Liz, you need a man with backbone. Taylor was idealistic and friendly and good-hearted, but what a pancake. Flat. Boring. Wimpy. Pass the syrup.”

“Molly, please. He wasn’t that bad.”

“Have I been married twice, Liz? Do I know the good ones from the bums?”

“Apparently not. Case in point—Joel.”

Molly stood. “Yes, but I’m not marrying Joel. He’s a friend.”

“You’re sleeping with your friend, Molly. That’s a dumb thing to do. Have I told you that before?”

“Two thousand times. It’s in my DNA to do dumb things with men.”

Liz stood and picked up her purse. “Molly, please stop living this way. You don’t need Joel. You don’t need men who are bad for you. Why do you do that to yourself?”

“For the same reason you dated Taylor. He was there, you were lonely and it felt good at the time.”

“I didn’t sleep with Taylor. When I figured out he wasn’t right for me, I got out pretty easily. You’re tangled up all over again, Molly.”

“And you can’t stop thinking about Sergeant Joshua Duff. We’re the same.” She tossed the refugee update on Liz’s desk. “Let’s hurry up and pray, because I need to get some time on my treadmill before Joel comes over.”

“All right, all right. I’ll start.”

The women had been friends for a couple of years. Liz had talked Molly into going to church not long after they’d met at the refugee agency. Now they prayed together at the end of every workday.

But Molly’s life didn’t change. She kept plunging from one mistake into another. As Liz took her friend’s hands and bowed her head, she had to wonder how different they really were.

“Gangs.” Sam Hawke tossed Joshua a white T-shirt from a stack on the desk in the front office. “Get used to it. This is the Haven uniform. We don’t allow gang colors in here.”

Joshua unfolded the cheap cotton garment. He had spent most of the afternoon under an oak tree in Forest Park, using his laptop to search out jobs and apartments for the Rudi family. It was high time to complete this assignment and move on to the next, he had decided.

The Marines had kept Joshua busy and in the thick of action for nearly a decade. Reflection and contemplation didn’t sit well with him—especially when his own thoughts were so troubling. The pitiful condition of the Somali family he and Liz Wallace had met at the airport disturbed him. Liz disturbed him more.

But Sam’s mention of gang activity piqued his interest. Maybe his military skills could be useful in St. Louis.

“Which gangs are causing you problems?” he asked, recalling the two he knew. “Crips and Bloods?”

“Around here, Crips are usually called Locs. Bloods are Dogs. We’ve got Murder Mob, Sets, Your Hood, Homies, Peoples, Cousins, Kinfolks, Dogs. Girls’ gangs are called Sole Survivers and Hood Rats. The Disciples and the 51 MOB are unique to St. Louis. Hispanics have ’em, too—mainly the Latin Kings, but Florencia 13 is making inroads.”

Joshua frowned. The St. Louis gangs sounded as complex as the factions he had encountered in Afghanistan and Iraq. Those sects had been founded on religious differences, but their current enmity went far beyond matters of faith.

“What’s the gangs’ focus?” he asked. “Territory? Violence?”

“Those are part of it. Arms and drugs play a big role. Just like everywhere, gangbangers worship the idols of the modern world—money, power and sex.”

Sam leaned against the edge of Terell’s old steel desk and studied the youngsters playing basketball on the large court just beyond the office window. “Our black gangs deal in crack and powder cocaine, marijuana, black tar heroin, powder heroin and heroin capsules. The Hispanics used to handle mostly commercial-grade marijuana. When Missouri clamped down on local methamphetamine producers, Mexican ice exploded. We’re doing all we can to keep tabs on what’s moving through the city.”

“Who’s we? ”

“Haven. But there are others.” He held up a hand and began ticking off the groups. “The St. Louis County Gang Task Force. The Metropolitan Police Department Gang/Drug Division’s gang unit. GREAT, the Gang Resistance Education and Training program set up by the mayor, works in elementary and middle schools. REJIS is an agency that notifies parents of a child’s gang affiliation. Cease Fire is a coalition of law enforcement, school and government officials, clergy and crime prevention specialists. We’ve got citizens’ groups, too—INTERACT, African-American Churches in Dialogue, the St. Louis Gang Outreach Program, you name it. But no one’s winning this war.”

Leaning one shoulder against a post, Joshua unfolded the T-shirt. “African-Americans, Latinos—sounds like the gangs run along racial lines.”

“Typically. A new gang showed up this summer, though. Hypes. They’re unusual—racially mixed.”

“So what binds them?”

“As near as we can figure, it’s their leader. Fellow goes by the name Mo Ded.”

“Sounds more like the definition of a cult to me—a group focused around a single charismatic person.”