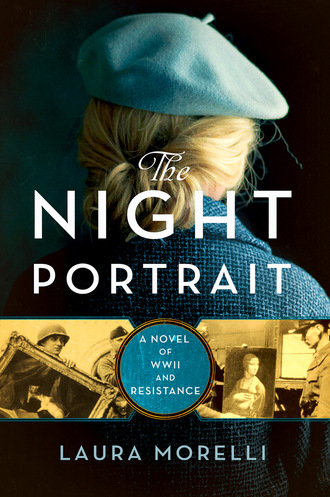

The Night Portrait

Cecilia reached for the next line of the song. She sensed the familiar feeling of emptying her chest of air at the same time that she filled the air in the room with her voice. She concentrated on the formation of the words. Surely they could hear the pounding in her chest as much as the bright sound from her lips?

If she had had more time to prepare, she could have accompanied herself on the lute or the lyre, Cecilia thought. She had spent many hours playing and picking out notes to her own ear. But this is not how things would be done at the court of Milan. Marco, the court musician, did his job. He played effortlessly, watching Cecilia with a warm expression, letting his fingers pluck the strings of his lute as if with little thought.

Buoyed by Marco’s calm assurance, Cecilia dared to look into the crowd now. Her eyes landed on her brother, with his rapt expression, his frank smile. She tried to avoid looking at her mother, whose eyes were cast to her fingers fidgeting in her lap. Cecilia continued to sing each line with greater precision and power.

She would never have such an audience in a convent, Cecilia thought, or anywhere else for that matter. This was her one opportunity to work her way into the life of this palace, into another life altogether. Her one chance to escape inevitable imprisonment, of unthinkable tedium, behind the walls of a convent. One chance to avoid spending the rest of her days with a needle and thread alongside her mother, who would only spend the rest of hers criticizing Cecilia’s stitches. One chance to win the heart of a man who might transform her life with a wave of his hand. As long as she kept him captivated, that is. But Cecilia knew how to talk to men, how to advocate for her desires. I have to make this work, Cecilia thought as she reached the last line of the song. This may be my last opportunity to make something substantial of my life.

In the long moment of dead silence that followed the last note, her brother nodded his quiet approval. Marco pressed his palm to the lute strings to quiet them, then smiled at Cecilia. Then, suddenly, a deafening roar of applause filled the chamber. One of the men cried, “Brava!” A few of the palace guests stood and called out more verbal bursts of approval.

Only then did Cecilia find the nerve to set her eyes on Ludovico il Moro, seated in the center of the group. His chin lifted high, his expression was nonetheless difficult to interpret. His jaw was set and squared, but his dark eyes did not leave Cecilia’s face. Then, she detected one corner of his mouth rise.

Cecilia felt something like intoxication, bliss, fill her now. The sound of applause began to quell but the feeling stayed. She took a small, unpracticed curtsy.

This is it, she thought to herself. I’ve done it. This is what I was meant to do. My family. They will see. This palace. This court. This man. All of it is within my reach.

Northern France

August 1944

IN DOMINIC’S DREAM, SALLY STOOPED OVER A BASKET, pulling out a damp sheet with the businesslike strength that Dominic still found astounding in her petite figure. Her hair was tucked neatly behind her ears as she shook out the sheet and swung it onto the long piece of twine they had tied between two trees.

“Hello, ma’am,” Dominic said, taking off his cap. He pulled her close, smudging sweat and coal dust down the front of her dress.

“You need a bath,” she said in her crisp Irish accent, a fake scowl on her freckled face. Then she pressed the length of her body against him to kiss him with a passion that set him on fire.

Waking was like having shards of ice pushed through his heart. Dominic stirred to the harsh reality of the bottom bunk, his thin body separated from the metal frame by what seemed like half an inch of dirty mattress. He lay there, rendered motionless by agony for a few moments, then gazed listlessly at his surroundings. All around him, his comrades were smoking, nibbling on rations, lying on their beds and staring at the gently moving canvas ceiling of the tent. The floor was already damp with rain. Had it only been a few hours since they had pitched it? Perhaps they’d have the luxury of staying in the same place for a few days this time. Dominic had lost track of where they were now. France, Belgium—some forsaken corner of wet and war-torn Europe. He was weary of it already, at the same time marveling that he was still alive, that he had survived the brutal landing on the beaches and the intense gun battles that had ensued.

None of the others were paying him attention. Judging by the soft snoring coming from the top bunk, Paul Blakeley, the lanky private from San Antonio who had been commissioned with Dominic in a Military Police unit at Camp Glenn and shipped off to Normandy, was asleep. Dominic rolled over to his little knapsack and pulled out a scrap of paper he’d scavenged from outside the officers’ tent. It had been crumpled up and tossed to the ground, but despite the fragments of a telegram printed on one side, to Dominic it was pure gold. He’d also scrounged a stick of what passed for charcoal from a smoldering forest they’d passed a few days ago. And now, finally, he could bring the two together.

There was no question of what he would draw. The charcoal stick was forming her familiar curves on the paper before he could even ask himself the question. He drew her the way he loved her best, curled on her side in bed, her loose hair a tangle against the back of her neck. Even in black and white, in his mind, he could see the burning color of Sally’s hair on the pillow.

Suddenly, a grubby hand came down and grasped roughly at the paper. Instinctively, he snatched his hand back, but a tiny tear appeared in one corner and he reflexively let it go.

“Well, have a look at this!” boomed a coarse voice. “Who is this sizzling lady?”

Dominic rose to his feet, face burning. Private Kellermann was a towering mass of a man, with the thick shoulders and manner of a rhino. He held the sketch up to the light and laughed, the sound rolling out of him on a tide of vulgar intentions. “She’s a beauty, Bonelli. Don’t you want to share?”

Dominic’s fingers curled into fists. The idea of Kellermann’s eyes on even a fleeting likeness of his wife set his blood on fire. “Give it back,” he said.

But the other soldiers were already gathering around; a sweaty, smelly horde of half-starved men who hadn’t seen a living woman in months, and Dominic’s lifelike portrayal of his wife was more than enough for them. Hooting and yelling, they passed the sketch between them, and with each grubby thumbprint that stained the page, Dominic’s blood rose. Wolf whistles pierced the air as Dominic rushed from one man to the other, snatching at the precious sketch, but his slight frame kept him just out of reach of it as they passed it back and forth above his head.

“Jump, Macaroni!” one man’s voice howled. “Jump for your lady!” Dominic brushed off the all-too-familiar slur.

Finally, Kellermann had the picture again, and he waved it easily and tauntingly above Dominic’s head, leaning back against his bunk. “You heard the man, Macaroni!” he cackled. “Jump!”

Before Dominic could respond, the motionless lump that had been lying in the top bunk sprang suddenly to life. Paul’s hand flashed out from under the blankets and swiped the paper clean out of Kellermann’s hand in one brisk movement. Turning indignantly, Kellermann opened his mouth to protest, but when Paul sat up, he thought better of it. While Dominic’s bunkmate spoke with a Texan twang, his great height and clear blue eyes spoke of some Scandinavian ancestor that had chewed on shields in a berserker rage on Viking longboats a thousand years ago. The expression in his face warned Kellermann that he’d think nothing of doing something similar right now.

“Enough.” Paul didn’t speak much, but when he did, men listened. The group of men dispersed in bits and pieces until only Dominic was left, arms folded, staring Kellermann in the eye even though he had to tip his head back to do so. “That’s his wife, man. Stop it.”

There was a moment of icy silence between them, then Kellermann let out a scathing belly laugh. “Enjoy your little art project, wop,” he growled. “We’ll be off fighting a war.” He slouched off, turning his broad back only to spit on the floor a few feet from Dominic’s boots.

Seething, Dominic turned back to his bunk. Paul held out the drawing to him. “Thanks,” Dominic said, taking it back, surprised at how much his voice was shaking. He smoothed the paper between his rough fingers.

The silence stood heavy and painful. Paul pushed it gently aside. “It’s a really good picture,” he said quietly, his Texas twang softening the thick air between them. Paul had been a stalwart comrade ever since they’d ended up as bunkmates in boot camp. He was one of the few of their platoon who had survived the decimation on those grim beaches of Normandy. Paul’s sturdy good humor had made their slow advance over the devastated landscape less impossible. For all his size and quietness, Paul had quick hands and a quicker mind; the speed with which he’d plucked the drawing from Kellermann’s hands was echoed in card games and tricks by candlelight. Those moments were few and far between, not because they didn’t have idle time but, Dominic figured, because their spirit for games had been crushed on those beaches, all those weeks ago.

“I never knew you could draw, Bonelli,” Paul said.

Dominic shrugged, one-shouldered, then stood and began tidying the thin blanket on his bunk. “I’ve drawn since I was a little kid. I would have loved to go to art school, to find a teacher, but what could I do? I had to start working in the mines just after ninth grade. Then there was Sally, and the wedding, and Cecilia … and the war.” He touched his neck where the Saint Christopher medal was so conspicuously missing. “I just draw here and there when I’ve got a little spare time. Helps me relax, you know?”

Dominic realized that for all the time he and Paul had spent together since boot camp, they had only shared snippets of their lives back home. And yet, Dominic marveled, their time together in the face of ever-present threats had bonded them as if they had been together their whole lives. War could do that, Dominic supposed.

Paul had not spoken much of his family. Dominic knew that he had had little time for his father. The old rancher had fought in the Great War and come back broken; he had spent more time looking at the bottom of a bottle than at his son, and his family had suffered for it. Paul’s mother had wrestled five boys through the years of the Depression on a cattle ranch that was falling apart. It had been all she could do to feed the boys, let alone give them affection. Paul barely mentioned them. But he often mentioned Francine. He never once described the girl he loved as beautiful; but the look she put on his face certainly was. The mention of her name had lit him up from the inside out. Dominic knew the feeling.

“You always draw your wife?” Paul asked, his pale legs now dangling from the bunk above.

“Usually,” Dominic admitted, a smile creeping onto his face despite himself. “It’s always one portrait or another, though. I’ve drawn most of youse guys and slipped the pictures into my letters to Sally so that she can see what you look like.” He grinned.

“Sneaky. I knew I had to look out for you!” Paul joked. “Who’s your favorite artist?”

Dominic shrugged again. “I used to go down to the library when I was a kid to look at paintings in books. The old masters—Rembrandt, Rubens, you know. But Leonardo da Vinci was always my favorite. I suppose he’d have to be, being Italian and everything.”

“Ever been to Italy?”

Dominic shook his head. “My parents couldn’t wait to get out of there and make a new life in America. I guess they’re more American than Italian, really—they’ve got a full-size photograph of me in my uniform with a giant American flag.” He huffed out a laugh, then smoothed his hand down the front of the stained and tattered remains of his uniform, now a ratty shadow of the splendor that had been photographed that day. “I’d love to visit there someday, though. It would be something to see those masterpieces in real life.”

The bunk creaked as Paul flipped onto his back again, his voice growing muffled. “Someday you will, I reckon.”

Dominic wished he could share Paul’s optimism. He couldn’t emulate it, but he was grateful for it. Moments of peaceful conversation about anything other than war had been few and far between. Dominic had lost count of how many skirmishes they’d been in; each time his survival seemed even more like a miracle. Had Dominic’s little unit made a dent in the war against the Nazis? Had they made any difference at all? Even after all these weeks of narrow misses, he wasn’t sure. He only knew he had to keep going, had to keep focused on their mission to win this war. His officers complimented him on his sharpshooting skills and dedication to protecting other soldiers, but he knew that the only reason he was still here was luck. And perhaps the prayers of his mother, all the way back home across the ocean.

“Attention!” A sharp word from the door of the tent brought every soldier to his feet as automatically as machine-gun fire. They stood neatly side by side, feet together, arms by their sides, bodies as straight as their exhausted muscles could make them. An officer walked into the tent, the glittering badges on his shoulders marking him as a major. There was utter silence but for the squish of his boots in the mud that had pooled on the floor of the tent.

The major strolled down the twin lines of men, examining the names embroidered on their uniforms.

“Blakely!” he cried.

Then, his eyes settled on Dominic.

“Bonelli!” he boomed.

“Sir!” Dominic saluted.

“I hear you’re a good cover.” The expression in the major’s dark eyes was unreadable. He quirked an eyebrow. “Come. We have a job for you. Don’t want to keep the commander waiting.”

Milan, Italy

January 1490

“COME. YOU MUST NOT KEEP HIS LORDSHIP WAITING.”

Cecilia’s underarms raged as if a dozen bees were stinging her skin at once. Reluctantly, she raised her arms in the air again. Wearing only her sleeveless linen chemise, Cecilia let Lucrezia Crivelli, the dressmaid, fan her underarms with fluttering hands. Around Cecilia’s bedchamber, a dozen gowns in silk, satin, and velvet lay across every surface.

“Aya! What’s in this?” Cecilia huffed out three strong breaths, staving off the pain.

“A little quicklime, some arsenic, pig lard. A few other secrets. A favorite recipe of His Lordship’s mother. Not much longer,” Lucrezia said. “You’re supposed to say two Our Fathers.”

“Our Father, who art in heaven …” Cecilia began, but her voice trembled. She shivered in the frigid air and squeezed her eyes shut against the stinging.

“Get used to it. His Lordship doesn’t like his women with hair on their bodies.”

Cecilia opened her eyes wide now and stared at Lucrezia, a girl about Cecilia’s age who was tasked with attending Cecilia and helping with her hair and dress. She examined the girl’s wide, brown eyes to see if she might be teasing her. “Really? Nowhere on the body?”

Lucrezia shook her head. “We’ll do your pòmm next. Keep going.”

Cecilia didn’t know any Milanese words, but she could guess which body part might be up for the next depilation. She squeezed her eyes closed again, pushing through the cold and the nearly unbearable stinging. She got through the prayers, spitting them out as quickly as she ever had. While she prayed, Lucrezia dabbed at Cecilia’s underarms with her fingertips.

When Cecilia completed her Our Fathers, Lucrezia went to the hearth, where a pot roiled over the fire. She dipped a cloth into the water with tongs, then wrung it out and placed the steaming fabric under Cecilia’s arm.

“Aya!” The cold was replaced with scalding heat. Lucrezia roughly wiped away the vile mixture from both underarms, taking the hair out with it from the roots. At last, Cecilia let her arms, nearly numb, fall to her sides. She grasped a brown velvet mantle from a nearby chair and slung it over her shoulders. She brought her fingertips to her underarms, where the bare, raw skin throbbed but was undeniably smooth and hairless. The stinging, lingering but more tolerable, continued as Cecilia walked to the bed. She ran her palms lightly over the pile of dresses. Green satin. Purple velvet. Red silk with black lace and gilded wire threaded through the neckline.

“They are so beautiful,” Cecilia said. In fact, the dresses were the most beautiful things Cecilia had ever seen.

“Castoffs. You’ll need them altered to fit you. You’re a scrawny thing,” Lucrezia said, pressing her hands into Cecilia’s waist so hard that Cecilia flinched. Lucrezia shrugged. “We just pulled these from the wardrobe of the last mistress.”

A long pause. “The last mistress?”

Lucrezia nodded.

“What happened to her?”

“Oh!” A nervous laugh. “She didn’t last long.”

“Why not?” Cecilia studied Lucrezia’s face again to see if she might be setting herself up to be the butt of a joke.

“His Lordship tired of her quickly,” Lucrezia said, her voice suddenly sad in a way that, to Cecilia, sounded anything but sincere. “If you want to know what I think, it’s that she talked too much. Whatever the case, His Lordship’s … diversions … are usually brief anyway. Only little Bianca stayed behind.”

“Bianca?”

“Poor little bastard child.” Lucrezia shook her head. “She is a beauty, though. Hair as black as midnight. Just like her father’s.”

Cecilia flopped into a chair next to her bed and pulled the mantle tightly around her shoulders. Had she stepped into waters that might close quickly over her head? She wondered how many other important things she did not know.

A knock at the door. Lucrezia ushered in a gray-haired woman in a chambermaid’s dress. The maid uttered something to Cecilia in Milanese dialect, then bowed her head and extended a folded parchment with a wax seal. Cecilia recognized her brother’s elegant handwriting on the parchment but she hesitated. It was the first time anyone had ever bowed to her, and besides, Cecilia had no idea what the maid had said. The old woman met Cecilia’s eyes and smiled. Lucrezia stepped in and took the letter from the maid’s hand, then gave it to Cecilia. “A letter for His Lordship’s flower.”

Munich, Germany

September 1939

EDITH BRACED HERSELF AGAINST A METAL DOORFRAME as the train whistle sounded and the wheels screeched. She pressed herself against the window and watched the twin onion domes of Munich’s Frauenkirche recede into the dusk.

For weeks, Edith had been preparing herself to watch Heinrich board a train for Poland. She had pictured their farewell a thousand times, Heinrich handsome, tall, and lean in his uniform. She imagined herself running along the platform, pressed into a crowd of women as the train pulled out of the station.

Never did Edith foresee that she would be the one fastening up the buttons on a starched field jacket that had been cursorily modified to fit a woman’s shape. That she would be the one boarding the huffing train for Kraków, watching from the window while Heinrich ran along the platform waving, growing smaller as the train pulled eastward from Hauptbahnhof Station. Now she was the one holding conscription papers. There was no refusing the call. Her orders were little more than a signed, stamped shred of paper, a single folio that had the power to change her entire life. Maybe even to take her life, if she were one of the unlucky ones.

Behind her back, Edith heard a low whistle, a catcall that made the hairs on the back of her neck rise.

“He! Klaus, they have skirts here!” the soldier yelled over his shoulder to someone in the line behind him.

“Excuse me, madam,” the man said mockingly as he squeezed past Edith standing by the train window, pressing himself against her back more closely than necessary as he pushed through the narrow train corridor.

She refused to honor his vulgarity with a reaction, but her nerves were ruffled. Edith moved away from the fresh air in the window. She opened the door to a passenger car and made her way down the center aisle. The train car was filled with men, most wearing the same field jacket as her own, others in civilian clothes. She glanced beyond them, struggling to keep her emotions in check. She knew her eyes had to be red, her cheeks puffy. She felt their gaze on her as she hurried down the aisle, managing her large bag.

In the stifling air of the sleeping car, Edith finally exhaled. It was tightly spaced with two stacks of bunks, empty. All the other cars like this were filled with five or six soldiers. Being a woman, they had assigned her one to herself. Edith pressed herself into one of the lower bunks and turned her thoughts again to Heinrich.

Please tell me that you are not already taken.

Edith smiled even now through the blur of tears, thinking of Heinrich’s first words to her, two years ago, at a Bavarian festival in a popular Munich beer garden.

“Pardon me?” she had said to the tall stranger who pushed through the crowd of revelers, the handsome man with the lock of blond hair over his brow who dared to be so forward.

“You’re a beautiful woman,” he had said. “I only hope that someone has not already stolen you away so that the rest of us might have a standing chance.”

She’d laughed at him, admiring his audacity. Edith had always considered herself as plain as a kitchen mouse and had come to accept that she may spend her days as a spinster at her father’s side. The mere thought of Heinrich still had the power to make her stomach flutter, even when she conjured images of their first few headlong days together.

It was a daring beginning, but even after getting to know each other over months, Heinrich had truly won her heart. And when he came to her father to ask for his daughter’s hand in marriage, Edith’s heart had been forever his. Heinrich knew that her father may not even remember his name, but all the same, he had treated him with respect and tenderness.

“Yes,” her father had said, and she knew that in that moment, there was not only clarity in his mind, but happiness in his heart.

A sliver of dim light remained outside the narrow window, but Edith was too filled with nervous energy to settle in her bunk. Instead, she stood again, turned her canvas bag on its side, and pulled out a small notebook. She stared at the blank page. Should she write a letter to her father? Would he understand where she had gone? Would he remember her at all?

Her neighbor, Frau Gerzheimer, had seemed more than willing to help. Edith held out hope that Frau Gerzheimer would have what it took to convince her father to cooperate. She trusted that Heinrich would stop by after working at his father’s store to make sure everything was all right, before he, too, had to board a train. And she prayed that the agency would send a relief nurse as soon as possible. The last thing she wanted was to see her father sent to a sanatorium where he might wither away.

Unable to find the words to say to her father, Edith put the pen to the paper and started a letter to Heinrich, but all she could think to write was how much she already missed him. Edith and Heinrich were heading separately to Poland, both pawns in a game that had grown larger than themselves. Names whispered to block leaders for the slightest suspicion. Jewish neighbors—men, women, even innocent children like the little Nusbaum boy—led from their homes in dark silence, amassed, corralled, and shifted like human game pieces on a great chessboard. And boys no older than fourteen, marching in uniform, their voices echoing in the streets.