Полная версия

Shouldn't You Be in School?

“What is the whole thing?”

“I told you, we shouldn’t say a word about it.”

“How can I say a word about something I don’t know about?”

She did not answer but got out of the car and slammed the door unnecessarily hard. I did the same. “Prestigious” is a word which here means “important or having great influence,” although the Department of Education didn’t look prestigious as we approached the door. It was a tall, thin building, sagging against another tall, thin building to its right, and being sagged on by a tall, thin building to its left. The tall, thin buildings kept going, saggy and shabby, all the way down the block, like grass curved over in the wind. Just over the door was a cardboard sign reading DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION that I wanted to remove, just so I could see the words ROE HOUSE that were probably carved into the stone beneath it.

Before we could get to the door, it opened and a man walked out, putting on his hat and taking out a cigarette. Theodora nodded to him as he held the door open, and he turned briefly to her and said something she had to ask him to repeat.

“Do you have any fire?” he repeated.

“We are in fact here to investigate a case of arson,” Theodora said, “but that is a secret I am not to reveal.”

The man frowned impatiently and pointed to his cigarette to show what he meant. The cigarette sat tucked in his mouth, hanging over his beard, unlit.

“Oh!” Theodora said. “No, I’m sorry, I don’t have any matches.”

The man turned his eyes to me and I shook my head. I did in fact have a box of matches in my pocket, but I don’t think adults should be encouraged to smoke. He frowned again and started to walk away before turning around and asking me a question.

It is not a question anyone enjoys hearing, especially people my age. It is the question printed on the cover of this book.

“I’m in a special program,” I said, as Theodora stepped inside the building.

“Are you indeed,” the man said. It didn’t sound like it was news to him, or perhaps he just didn’t care much. He reached up and took the cigarette out of his mouth and turned around and walked away. I watched him, but I didn’t know why. He looked like nothing to watch. He was just a man, moving quickly down the block. At the corner he tossed his cigarette into a dented trash can with a noise louder than it should have been. Most of Stain’d-by-the-Sea’s trash cans were as empty as its sidewalks. I stopped watching and followed Theodora in.

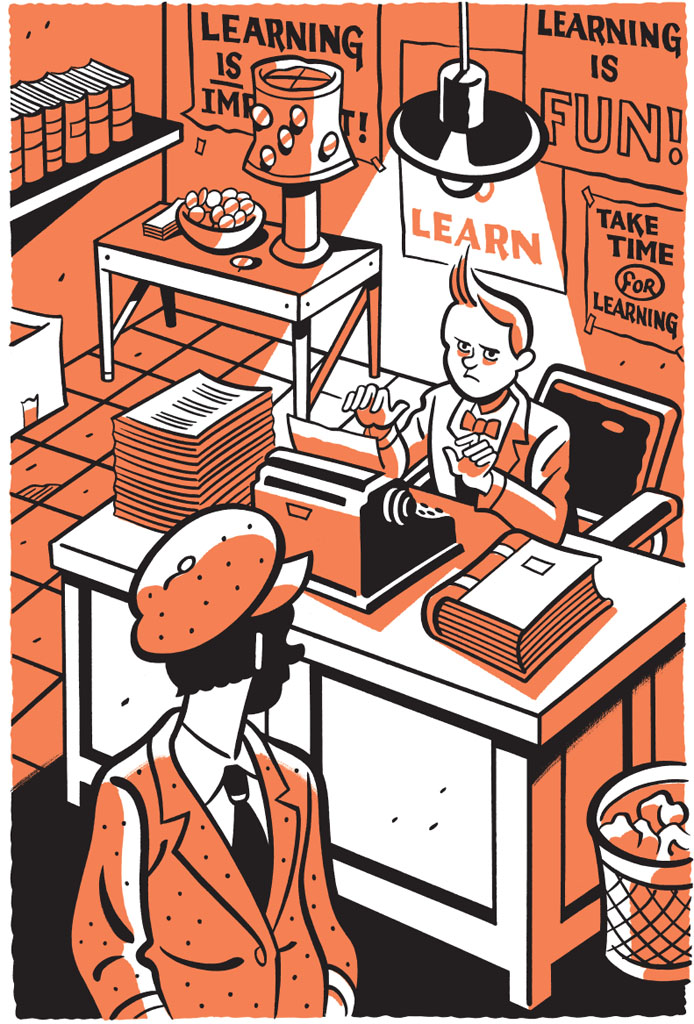

I’d expected to be in the large, empty room Moxie had shown me in the photograph. Instead I found myself in a small waiting area, separated from the large room by a wall that looked like it would fall over if you gave it one good push. In the middle of the wall was a swinging door, not swinging, and tacked to the door was a sign that said WELCOME TO THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, WHERE LEARNING IS FUN! LEARNING IS IMPORTANT! said another sign, on another wall. There was one that said BOOKS ARE FOR LEARNING! that hung over a bookshelf, and one that said TAKE TIME FOR LEARNING! hanging over a table. On a table were a stack of stickers reading LEARNING! that you could affix to the bumper of your car or boat, and a bowl of badges reading LEARNING! that you could pin to your shirt or jacket or lampshade. They’d pinned a few of them to the lamp’s lampshade, was how I knew, along with a small sign that read LEARNING! It seemed like a lot of learning.

There was a boy about my age going clickety-clack into a typewriter at a large wooden desk. His hair had been trimmed into a sort of tilted spike, like the fuse on a stick of dynamite, and his eyes were wide and not looking at us. When he was done typing the page, he took it out of the typewriter and put it on a large pile of other pages. Then he started up on another sheet of paper. He typed faster than I’d ever seen Moxie type, much faster. His hands hardly moved around the keyboard, as if he were typing the same thing over and over again. There had been a sign pasted onto the side of the desk, and the sign had probably said LEARNING!, but somebody had tried to unpeel it and now it was just a scratchy white mess, like a cloud you might stare at after a picnic. Through the flimsy wall I could hear more typewriters, plus the shuffle of papers and the other muttery noises of a busy office, but the boy behind the desk was the only person from the Department of Education to be seen.

“S. Theodora Markson,” announced S. Theodora Markson, “and her associate. We have an appointment.”

“Please wait,” the boy said, without looking up from his typing.

Theodora sat in one chair and I sat in another, near the bookshelf. I took down a book that had been recommended to me by several people I didn’t like.

The swinging door swung, and a tall, neatly dressed woman strode to the desk where the boy was typing and took a few papers from the tall pile. Pinned to her collar was a very shiny gold badge shaped like a lime, and pinned to her face was a smile that shone much less brightly. Theodora stood, but the woman did not look at us or say anything, just retreated back into the busy office. Theodora sat. I tried the book. A man gave his son Jody a pony, and Jody had to promise to take care of it. Then the pony got sick. I could see where this was going and put the book down. It was more pleasant to sit and think what the cloud looked like.

We waited awhile. The boy kept typing and typing and typing and then finally stopped but he was just scratching his elbow and then he was typing again. The tall woman made several trips through the swinging door and back again without looking at us. Theodora took up the book and seemed quite interested in it. I stood up. He might not talk to me, but I would talk to him, so I asked him if it would be much longer.

“I don’t know,” he said, and typed and typed and typed.

“You don’t have to look busy on my account,” I said.

Now he stopped. “I look busy because I am busy.”

“So you say,” I said.

“You don’t have to take my word for it,” the boy said, and pointed to the pile he was making. “Look at what I’m typing if you don’t believe me.”

“I’m not a math tutor,” I said. “I don’t feel the need to check your work.”

“The Department of Education is a very busy office. We’re in charge of every pedagogical institution in Stain’d-by-the-Sea. Read about us in the newspaper if you don’t believe me.”

“Why wouldn’t I believe you?”

“All right then, Snicket.”

I sat down and then stood up again. “You know my name, but I don’t know yours. That doesn’t seem fair.”

“It’s Kellar,” the boy said. “Kellar Haines.”

“Well, Kellar Haines,” I said, “shouldn’t you be in school?”

Kellar had been ready to start typing again, but now he blinked and looked down at his fingers. They were trembling a little bit. “Yes,” he said, and there was something about the way he said it, quiet and sad, that made me see the two of us a little differently.

The door swung open again, and the woman with the lime pin came out and looked at us at last. Then she looked at Kellar Haines. Then she looked behind her and then she smiled nervously and then she began to speak.

“Good morning” is what she said. “I’m Sharon Haines. I work here, which is the Department of Education. Yes, that is what it is.”

“I’m S. Theodora Markson,” said S. Theodora Markson, “and never mind who this is.”

“Lemony Snicket,” I said.

“This is my son Kellar,” Sharon said, “and never mind him, either.”

Sharon gave a little nod to indicate Kellar, and Theodora gave a little nod in my direction. Then they both smiled, Theodora first and Sharon after a few seconds, like a mirror running late.

“Perhaps we should talk in your office,” I said.

“Yes, of course,” Sharon said, leading us to the swinging door, and then she gave a sort of gasp. “No, let’s just sit here, shall we? The Department of Education is very busy today. Very busy. And my desk gives me some kind of medical condition. My tongue swells up if I sit there too long, and I end up talking like my mouth is full of baby mice.”

She sat down between us, and I watched Theodora nodding seriously at Sharon the way one adult has nodded at the nonsense of another adult since the first adult walked on the earth. “I think I have a medical condition, too,” Theodora said. “Lately when I’m driving my roadster I have the peculiar sensation of everything being quieter than it should be.”

“That could be because your helmet covers your ears,” I said.

The two women looked at me the way you look at a leaky pen. I looked down at the floor. There was an ugly rug with ugly triangles on it in an ugly pattern. Underneath, I thought, were the rectangular marks I’d seen in the photograph. I wondered what was covering the floor in the office, on the other side of the flimsy wall. Desks, chairs. Whatever all those muttering people kept in their office.

“Perhaps I’d better tell you about the case,” Sharon said, and she went to her son’s desk and took something out of a drawer. It was a photograph, but we couldn’t see it. It was facedown, and she left it that way in her lap when she sat back down. She sighed and looked behind her. Behind her was a wall. “There is a villain,” she said, “who is putting every schoolchild in town in terrible danger.”

I knew it, I thought.

Sharon gave us a long look. Kellar went type-type-type. “We have had some dealings with such a villain,” I said. “It would probably be best not to say his name.”

“It’s Hangfire,” Theodora explained.

Type-type-stop.

“Hangfire,” Sharon repeated with a frown. “What do you know about him?”

“Not much,” Theodora said. “He’s violent and treacherous. You know the kind of man I mean.”

“Yes, I do,” Sharon said, with a nervous smile. Kellar started typing again. “I had a boyfriend like that in eighth grade.”

“Me too!” Theodora was using a tone of voice I hadn’t heard from her before. I regret to say that I’d have to describe it as a squeal. “He was always saying impolite things about my hair.”

“Well,” Sharon said, “I think it looks nice.”

“Well,” Theodora said, “I think you’re nice.”

“Nevertheless,” I said, spoiling the party, “we’re here to talk about Hangfire.”

Sharon sighed again and rattled her fingers on the photograph. “Recently a local business was burned to the ground,” she said. “Birnbaum’s Sheep Barn caught fire in the middle of the night, and there was scarcely enough time to evacuate the sheep. The fire was not an accident. It was a crime.”

Theodora turned to me. “She means arson,” she explained, unnecessarily. You could not become an apprentice without knowing what arson is. You could not even start to study for an apprenticeship without knowing “arson.” I even knew the original Latin term from which the word “arson” was derived.

“We’ll assign this case extra-crucial status,” Theodora said to Sharon, using an expression that meant absolutely nothing.

“I appreciate that,” Sharon said. “As luck would have it, there was a witness to the fire, and I’m hoping you and your apprentice will go interview this man and see if he can tell you anything.”

“A witness!” Theodora cried. “Aha! ”

“For instance,” Sharon continued, “he might say the arsonist had an unusual jacket, so it would help you find him and capture him.”

“Unusual jacket! Aha! ”

Theodora looked at me triumphantly, but I saw nothing triumphant about an imaginary jacket mentioned by a witness we hadn’t met yet.

“Who is this witness?” I asked.

Sharon’s eyes widened and she moved her hands up and down, over and over, like she couldn’t decide whether or not to remove her ears. She looked over at her son and then down at her collar, and then she cleared her throat and answered my question at last. “Harold Limetta is his name.”

“Harold Limetta?”

“Yes, Harold Limetta. I believe his name is Italian, although he lives here in town at 421 Ballpoint Avenue, walking distance from the library.”

“We’ll take my car,” Theodora said. “Thank you for meeting with us, Ms. Haines.”

“Call me Sharon,” Sharon said, “and call me the minute you have an update.”

“Of course I will,” Theodora said. “After all, our progress is being evaluated.”

Kellar stopped typing for a second and shared a look with his mother I didn’t quite understand, but every family has a look they give each other that makes no sense to anybody else. “Yes,” Sharon agreed, when the look was over. “Our progress is being evaluated. Do you have any more questions?”

“Yes,” Theodora said. “How can I reach you outside of office hours?”

“I’ll give you my number,” Sharon promised. “I must say, I didn’t expect so much kindness and understanding from such a prestigious investigator.”

“It is you who are prestigious,” Theodora said. “Come along, Snicket. We’re done here. Let’s head on over to Harold Limetta’s house.”

I was still staring at the photograph turned upside down on the desk. “I have a question,” I said. “Why are schoolchildren in danger because a barn burned down?”

Sharon sat up in her chair and straightened the creases on the coat she was wearing. I didn’t like the coat and I didn’t like its creases. “The Department of Education takes its mission very seriously,” she said to me. “Even one schoolchild in danger is a terrible thing. Children are the future of the world, and we must keep them safe from harm. Every night I tremble thinking about how I’d feel if something terrible happened, even if it happened to somebody I did not know.”

I made myself nod. I’d heard every word the woman had said, but I didn’t mistake it for something that made sense. Her fingers slipped under the edge of the photograph, and she slowly began to turn it over. “If this jacketed villain burned down a barn,” she said, “it stands to reason that he’d burn down a school.” She leaned forward and looked very sternly at me. “I can guarantee you, young man, that it will probably happen. If you don’t believe me, take a good, long look at this!”

With a flick of her wrist, like a magician at a birthday party, she turned the photograph over and I took a look. It was not a good, long look because there was nothing much to look at. It was a photograph of a barn, or at least it had been a barn, before it burned down. Now it was a great deal of ashes and a few lonely sticks of burned wood. The remains of a fire are not a nice thing to look at, but they are not a great danger to schoolchildren. I looked at the photograph and then I looked around the room I was in. There was no sign of the fishing industry. There was none of the necessary equipment described in Caviar: Salty Jewel of the Tasty Sea. Still, there was something fishy about the whole place. You might as well play along, I said to myself. Hangfire might be involved, and you might find Ellington Feint again and be able to keep your promise, and in any case Theodora is in charge, so you don’t have much choice, do you, Snicket? No, Snicket, I don’t. I looked at the photograph again, and then I looked at Sharon and thanked her for answering my question. We all stood up and said the usual things and Sharon led Theodora and me out of the Department of Education. I let the adults go out ahead of me and then stepped quickly back to Kellar’s desk.

“You know that restaurant Hungry’s?” I said. “You can find me there, when I’m not at the library or the Lost Arms.”

Kellar looked up at me and spoke very, very carefully, as if he were walking through shattered glass. “I’ll look up the address,” he said, “just like you’ll look up Harold Limetta.”

“Your mother already told us Harold Limetta’s address,” I said, and then Sharon walked back in. Kellar went back to his typing and I went out. Theodora was already in the roadster, pushing her head into her helmet. I stood on the sidewalk for a moment, wondering about both of the people I had met inside. It was hard to figure them out, but that is true of almost everything when it is very hot outside.

“That went very well, Snicket,” Theodora said. “I’m glad Sharon gave me her phone number. I’m going to call her this evening and give her a full report.”

“I think it’s nice you’re making friends your own age,” I said.

Her smile faded and she started the motor. “You should have listened to what she said, Snicket. She said our progress is being evaluated.”

“You’re the one who said that.”

“Well, Sharon agreed with me, and it’s true. If you were a better apprentice, you’d remember I told you that someone from our organization was keeping an eye on us.”

I remembered. Theodora was quite nervous about this person, whoever it was. I didn’t think it was likely that it was Sharon Haines of the Department of Education. I had my own ideas. “I did listen to what she said,” I said. “She thinks all of Stain’d-by-the-Sea’s schoolchildren are in danger because someone burned down a sheep barn. That doesn’t make much sense to me.”

“Well, I’m sure Harold Limetta will be able to tell us more.”

I looked down the empty block. The man who had asked for matches was long gone, of course. The dented trash can sulked on the corner. “Why would the Department of Education know about a witness to a fire?”

“It wasn’t just a fire, Snicket. It was arson. Any apprentice of S. Theodora Markson should know what that means.”

“What does the S stand for?”

She opened the passenger door. “Slide in, Snicket.”

I slid in and squinted out the window of the roadster. The sun told me that it was about noon. It also told me that it was going to continue to beat down on Stain’d-by-the-Sea and make it blazing hot and that there was no point in arguing with it, because it was the sun and I was a boy of about thirteen. The sun was right. There was no point in arguing. The roadster puttered us through Stain’d-by-the-Sea, and I didn’t say anything more to Theodora. She called herself an intrepid personage and said that was an expression which there meant an excellent investigator, and I didn’t correct her. She called me ungrateful and I didn’t disagree. I just sat in the heat and wished for an ice cream cone. Nobody brought me one. Maybe Harold Limetta has a freezer full of the stuff, I told myself. Peppermint ice cream in particular would really hit the spot.

But there was no freezer at 421 Ballpoint Avenue. I could tell that in a minute, when Theodora brought her automobile to a stop. A freezer is almost always made of metal, so when a house has been burned to the ground it usually remains there in the ashes, along with the oven, the wall safe, and any anvils lying around, each item a blackened gravestone for the home that has been destroyed. At 421 Ballpoint Avenue I could see a metal bench, which looked like it might have been by the front door, for taking off your boots. I could see a large set of small metal rectangles, each one about the size of a book, stacked up in several rows and surrounded by broken glass. I could see a metal picture frame, which might have held photographs of the Limetta children or grandchildren. But the rest of the house was nothing but ashes and smoke—thick gray smoke that was rising into the sky. I didn’t know if it would block the sun and make it cooler. I didn’t know whose pictures had been in the frames. I didn’t know what it meant that Harold Limetta’s house had burned down, just when we’d been sent to it. Fires were of grave importance to the organization of which I was a part. It would be a black mark on my record, I knew, to have suspicious fires occur and go unsolved and unpunished right under my eyes. Hangfire, I thought, I will find you and stop you. But I didn’t know how to find him. I didn’t know how to stop him. I didn’t even know for certain that this fire was his handiwork.

Ardere is the Latin, I thought. That’s what they said in ancient Rome when they were talking about fire. But that was all I knew as I stood and waited for the smoke to clear.

When the smoke cleared, there was something to see in the rubble of 421 Ballpoint Avenue, but it was the Officers Mitchum. I preferred smoke. Harvey and Mimi Mitchum were the only police officers in Stain’d-by-the-Sea, but they spent less time enforcing the law and more time bickering over just about anything that struck their fancy.

“And let me tell you,” Harvey Mitchum was saying to his wife, “that it was Agnes who had the idea, and Harry just played along, so by the time Philip had him cornered the crime had already been committed.”

“You’re a half-wit,” Mimi Mitchum said. “Carmen is the mastermind behind the crime, and if you can’t figure that out for yourself you might as well toss your badge into the ashes.”

“Carmen’s no mastermind,” Harvey said. “She’s even more dimwitted than you are.”

“How dare you call me dimwitted?”

“How dare you call me a half-wit?”

“It’s crueler to say that wits are dim than that they’re chopped in half !”

“Mimi, you’re only proving yourself dimwitted when you say things like that.”

“If I’m so dimwitted, how did I manage to solve the crime?”

One of the first things I’d learned upon arriving in Stain’d-by-the-Sea was that the only way to get the Mitchums to stop arguing was to interrupt them. “Excuse me, Officers,” I said, and the officers turned to look at me the way they always did. It is the way you look at a squeaky door when you are trying to be quiet.

“What are you doing here, lad?” Harvey Mitchum asked me.

“Did I hear you say you’ve managed to solve this crime?” I asked. It is always better to ask a question than to answer one.

“Harvey was just arguing with me about a movie we saw,” Mimi said. Her eyes moved suspiciously through the smoke from me to Theodora and back again. “How is it you happen to be here?”

Theodora put a gloved hand on my shoulder. “My associate and I were going to talk to Harold Limetta, the owner of this house, as part of an investigation.”

Harvey frowned and kicked at the ashes on the ground. “And who, precisely, has asked you to investigate?”

“I’d rather not say,” Theodora said.

“Well, I’d rather not have you poking through the scene of a crime,” Mimi said.

“And I’d rather not have that kid around here either,” her husband added.

“I’d rather not have you call me a kid,” I said.

“I’d rather not have my apprentice talk like that to the police,” Theodora said.

“I’d rather not have to listen to you discipline a child,” Harvey Mitchum said.

“I’d rather not listen to my husband boss people around,” Mimi Mitchum said.

“Sorry,” I said, “is it my turn? I have a long list of things I’d rather not do.”

It is not pleasant to have a number of people glaring and sighing at you at the same time, even if you meant for them to do it. As I’d planned, once they were done glaring and sighing, the Mitchums forgot all about asking us why we were there or who had sent us, and so the four of us were soon picking through the wreckage together as if we had never argued at all.

In one of my favorite books, a sad young man stumbling around outside finds a tiny strange man with a sack of magic crystals that change his life. My hopes weren’t that high, but I kept my eyes open. Almost anything would do. Any kind of clue would be better than what I had now. What I had now was bupkes, a word which here means “The Department of Education told us to go interview someone about a sheep barn burning down, only to find that the man’s house had burned down.” The metal bench was still there, and the metal picture frame with the photographs burned out of it. The metal rectangles were still there too, stacked up like the books you were planning on reading next. My shoes crunched on the shattered glass. They’re tanks, I realized. Tanks for fish or small animals. They’re tanks and they’d probably be clues, I thought, if you knew what the mystery was.