Полная версия

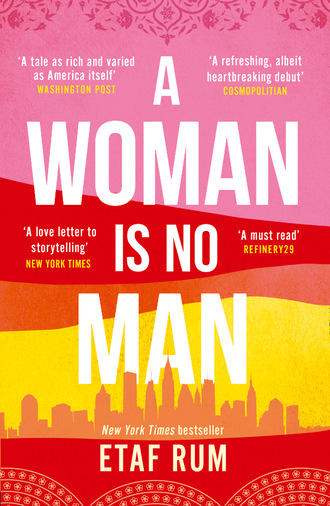

A Woman is No Man

Deya nodded as she stirred her soup. She wasn’t surprised Nasser knew what had happened to her parents. News traveled like wind in a community like theirs, where Arabs clung to each other like dough, afraid to get lost among the Irish, Italians, Greeks, and Hasidic Jews. It was as if all the Arabs in Brooklyn stood hand in hand, from Bay Ridge all the way up Atlantic Avenue, and shared everything, from one ear to the next. There were no secrets among them.

“What do you think is going to happen?” Layla asked.

“With what?”

“When you see him again. What will you talk about?”

“The fundamentals, I’m sure,” Deya said, one eyebrow cocked. “How many kids I want, where I want to live . . . you know, the basics.”

Her sisters laughed.

“But at least you’ll know what to expect if you decide to move forward,” Nora said. “Better than being taken off guard.”

“That’s true. He did seem very predictable.” Deya looked down into her soup. When she raised her eyes again, the corners crinkled. “You know what he said would make him happy?”

“Money?” said Layla.

“A good job?” added Nora.

Deya laughed. “Exactly. So typical.”

“What did you expect him to say?” said Nora. “Love? Romance?”

“No. But I hoped he’d at least pretend to have a more interesting answer.”

“Not everyone can pretend the way you do,” Nora said with a grin.

“Maybe he was nervous,” Layla said. “Did he ask what made you happy?”

“He did.”

“And what did you say?”

“I said nothing made me happy.”

“Why did you say that?” said Amal.

“Just to mess with him.”

“Sure,” Nora said, rolling her eyes. “That’s a good question, though. Let’s see. What would make me happy?” She stirred her soup. “Freedom,” she finally said. “Being able to do anything I wanted.”

“Success would make me happy,” Layla said. “Being a doctor or doing something great.”

“Good luck becoming a doctor in Fareeda’s house,” Nora said, laughing.

Layla rolled her eyes. “Says the girl who wants freedom.”

They all laughed at that.

Deya caught a glimpse of Amal, who was still chewing her fingers. She had yet to touch her soup. “What about you, habibti?” Deya asked, reaching out to squeeze her shoulder. “What would make you happy?”

Amal looked out the kitchen window. “Being with you three,” she said.

Deya sighed. Even though Amal was far too young to remember them—she’d been barely two years old when the car accident had happened—Deya knew she was thinking of their parents. But it was easier losing something you couldn’t quite remember, she thought. At least then there were no memories to look back on, nothing hurtful to relive. Deya envied her sisters that. She remembered too much, too often, though her memories were distorted and spotty, like half-remembered dreams. To make sense of them, she’d weave the scattered fragments together into a full narrative, with a beginning and an end, a purpose and a truth. Sometimes she would find herself mixing up memories, losing track of time, adding pieces here and there until her childhood felt complete, had a logical progression. And then she’d wonder: which pieces could she really remember, and which ones had she made up?

Deya felt cold as she sat at the kitchen table, despite the steam from her soup against her face. She could see Amal staring absently out the kitchen window, and she reached across the table and squeezed her hand.

“I just can’t imagine the house without you,” Amal whispered.

“Oh, come on,” Deya said. “It’s not like I’m going to a different country. I’ll be right around the corner. You can all come visit anytime.”

Nora and Layla smiled, but Amal just sighed. “I’m going to miss you.”

“I’m going to miss you, too.” Deya’s voice cracked as she said it.

Outside the window the light was getting duller, the wind settling. Deya watched a handful of birds gliding across the sky.

“I wish Mama and Baba were here,” Nora said.

Layla sighed. “I just wish I remembered them.”

“Me too,” Amal said.

“I don’t remember much either,” Nora said. “I was only six when they died.”

“But at least you were old enough to remember what they looked like,” said Layla. “Amal and I remember nothing.”

Nora turned to Deya. “Mama was beautiful, wasn’t she?”

Deya forced a smile. She could barely recall their mother’s face, just her eyes, how dark they were. Sometimes she wished she could peek inside Nora’s brain to see what she remembered about their parents, whether Nora’s memories resembled her own. But mostly she wished she would find nothing in Nora’s head, not a single memory. It would be easier that way.

“I remember being at the park once.” Nora’s voice was quieting now. “We were all having a picnic. Do you remember, Deya? Mama and Baba bought us Mister Softee cones. We sat in the shade and watched the ships drift beneath the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge like toy boats. And Mama and Baba stroked my hair and kissed me. I remember they were laughing.”

Deya said nothing. That day at the park was her last memory of her parents, but she recalled it differently. She remembered her parents sitting at opposite ends of the blanket, neither saying a word. In Deya’s memories, they rarely spoke to each other, and she couldn’t remember ever seeing them touch. She used to think they were being modest, that perhaps they loved each other when they were alone. But even when she watched them in secret, she never saw them show affection. Deya couldn’t remember why, but that day in the park, staring at her parents at opposite ends of the blanket, she’d felt as though she understood the meaning of the word sorrow for the first time.

The sisters spent the rest of their evening chatting about school until it was time for bed. Layla and Amal exchanged goodnight kisses with their older sisters before heading to their room. Nora sat on the bed beside Deya and twisted the blanket with her fingers. “Tell me something,” she said.

“Hm?”

“Did you mean what you told Nasser? That nothing can make you happy?”

Deya sat up and leaned against the headboard. “No, I . . . I don’t know.”

“Why do you think that? It worries me.”

When Deya said nothing, Nora leaned in close. “Tell me. What is it?”

“I don’t know, it’s just . . . Sometimes I think maybe happiness isn’t real, at least not for me. I know it sounds dramatic, but . . .” She paused, tried to find the right words. “Maybe if I keep everyone at arm’s length, if I don’t expect anything from the world, I won’t be disappointed.”

“But you know it’s not healthy, living with that mindset,” Nora said.

“Of course I know that, but I can’t help how I feel.”

“I don’t understand. When did you become so negative?”

Deya was silent.

“Is it because of Mama and Baba? Is that it? You always have this look in your eyes when we mention them, like you know something we don’t. What is it?”

“It’s nothing,” Deya said.

“Clearly it’s something. It must be. Something happened.”

Deya felt Nora’s words under her skin. Something had happened, everything had happened, nothing had happened. She remembered the days she’d sat outside Isra’s bedroom door, knocking and pounding, calling for her mother over and over. Mama. Open the door, Mama. Please, Mama. Can you hear me? Are you there? Are you coming, Mama? Please. But Isra never opened the door. Deya would lie there and wonder what she had done. What was wrong with her that her own mother couldn’t love her?

But Deya knew that no matter how clearly she could articulate this memory and countless others, Nora wouldn’t be able to understand how she felt, not really.

“Please don’t worry,” she said. “I’m okay.”

“Promise?”

“Promise.”

Nora yawned, stretching her arms in the air. “Tell me one of your stories, then,” she said. “So I can have good dreams. Tell me about Mama and Baba.”

Their bedtime story ritual had started when their parents died and continued throughout the years. Deya didn’t mind, but there was only so much she could remember, or wanted to. Telling a story wasn’t as simple as recalling memories. It was building on them and deciding which parts were best left unsaid.

Nora didn’t need to know about the nights Deya had waited for Adam to come home, pressing her nose against the window so hard it would still hurt by morning. How, on the rare nights he came home before bedtime, he’d scoop her into his arms, all while scanning the halls for Isra, waiting for her to come greet him, too. But Isra never greeted him. She never met his eyes when he entered the house, never even smiled. At best she’d stand in the corner of the hall, the color rushing out of her skin, the muscles in her jaw clenching

But other times it was worse: nights when Deya would lie in bed and hear Adam yelling on the other side of the wall, her mother weeping, then even more terrible sounds. A bang against the wall. A loud yelp. Adam screaming again. Deya would cover her ears, shut her eyes, curl up in a ball, and tell herself a story in her head until the noises faded in the background, until she could no longer hear her mother pleading, “Adam, please . . . Adam, stop . . .”

“What are you thinking about?” Nora asked, studying her sister’s face. “What are you remembering?”

“Nothing,” Deya said, though she could feel her face betray her. Sometimes Deya wondered if it was her mother’s sadness that made her sad, if perhaps when Isra died, all her sorrows had escaped and settled in Deya instead.

“Come on,” Nora said, sitting up. “I can see it on your face. Tell me.”

“It’s nothing. Besides, it’s getting late.”

“Pretty please. Soon you’ll be married, and then . . .” Her voice dwindled to a whisper. “Your memories are all I have left of them.”

“Fine.” Deya sighed. “I’ll tell you what I remember.” She straightened and cleared her throat. But she didn’t tell Nora the truth. She told her a story.

Isra

Spring 1990

Isra arrived in New York the day after her wedding ceremony, via a twelve-hour flight from Tel Aviv. Her first glimpse of the city was from the plane as they approached John F. Kennedy Airport. Her eyes widened and she pressed her nose against the window. She thought she had fallen in love. It was the city itself that captivated her first, immaculate buildings stories high—hundreds of them. From above, Manhattan looked so thin, like the buildings could just crack it in half, as though they were too heavy for that small sliver of land. As the plane neared the earth, Isra felt herself swell up. The Manhattan skyline turned from toylike to mountainous, its towers and citadels shooting upward like fireworks bursting into the sky, overwhelming in height and power, making Isra feel small, yet at the same time bewildered by their beauty, as if they were something out of a fairy tale. Even if she had read a thousand books, nothing could compare to the feeling she had now as she inhaled the view.

She could still see the skyline when the plane landed, though now it was a faint outline with a bluish hue on the far horizon. If Isra squinted, it almost seemed like she was looking at the mountains of Palestine, the buildings like dusty hills in the distance. She wondered what else she would see in the days to come.

“This is Queens,” Adam told her as they waited in line for a cab outside the airport. Once inside the minivan, Isra sat near a window in the back row, hoping Adam would sit beside her, but Sarah and Fareeda joined her instead. “It’s about a forty-five-minute ride to Brooklyn where we live,” Adam continued as he sat beside his brothers in the middle row. “If we’re not stuck in traffic, that is.”

Isra studied Queens through the taxicab window, eyes wide and watering in the March sunlight. She searched for the immaculate skyline she had seen from the plane, but it was nowhere in sight. All she could see were endless gray roads, curving and looping back in on themselves, with cars—hundreds of cars—zooming along them without stopping. Adam said they were two miles from the exit to Brooklyn, and Isra watched as the cabdriver merged to the left lane, following a sign that read BELT PARKWAY RAMP.

They sailed along a narrow highway so close to the water Isra thought the cab might slip and fall in. She didn’t know how to swim. “How are we driving so close to the water?” she managed to ask, eyeing a large ship in the distance, a cluster of birds soaring above it.

“Oh, this is nothing,” Adam said. “Wait until you see the bridge.”

And then it appeared, right in front of her, long and silver and elegant, like a bird spreading its wings over water. “That’s the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge,” Adam said, watching Isra’s eyes widen. “Isn’t it beautiful?”

“It is,” she said, panicking. “Are we driving on it?”

“No,” Adam said. “That bridge connects Brooklyn to Staten Island.”

“Has it ever fallen?” she whispered, eyes glued to the bridge as they neared it.

She could hear his smile in his reply. “Not that I know of.”

“But it’s so skinny! It looks like it could snap at any minute.”

Adam laughed. “Relax,” he said. “We’re in the greatest city on earth. Everything here is built by the best architects and engineers. Enjoy the view.”

Isra tried to relax. She could hear Khaled chuckle in the passenger seat. “Reminds me of the first time Fareeda saw the bridge.” He turned back to look at his wife. “I swear she almost cried in fear.”

“Sure I did,” Fareeda said, though Isra noticed that she still seemed nervous as they drove under the bridge. When they came out the other side, Isra exhaled hard, relieved it hadn’t collapsed on them.

It was only after they exited the parkway that Isra had her first glimpse of Brooklyn. It wasn’t what she had expected. Magnificent was a word you could put to Manhattan, but Brooklyn seemed plain in comparison, as though it didn’t belong alongside. All she saw were dull brick buildings covered in murals and graffiti, many of them dilapidated, and people pushing their way through the crowded streets with solemn looks on their faces. It puzzled her. Growing up, she had often wondered about the world outside Palestine, if it were as beautiful as the places she read about in books. She had been certain it would be, studying the Manhattan skyline, had been excited to call that world home. But now, eyeing Brooklyn through the window, seeing the graffiti scrawled on the walls and across the buildings, she wondered if her books had gotten it wrong, whether Mama had been right all along when she’d said the world would be disappointing regardless of where she stood.

“We live in Bay Ridge,” Adam said as the cabdriver stopped beside a row of old brick houses. Isra, Fareeda, and Sarah stood on the sidewalk while the men unloaded the suitcases. Adam held Isra’s suitcase in one hand and gestured around the block with the other. “Many of the Arabs in New York live in this neighborhood,” he said. “You’ll feel right at home.”

Isra surveyed the block. Adam’s family lived on a long, tree-lined street with row houses stacked against one another like books on a shelf. Most of the homes were made of red brick and curved in the front. They had two stories and a basement, with a short, narrow staircase leading to the front door on the first floor. Iron gates separated the houses from the sidewalk. It was a well-kept neighborhood—there were no open gutters or garbage littering the street, and the roads were paved, not dirt. But there was hardly any greenery—only a row of London planes lining the walk. No fruit to pick, no balcony, no front yard. She hoped there was at least a backyard.

“This is it,” Adam said when they reached the front gate of a house numbered 545.

Adam opened the front door and led her inside. “The houses here are quite cramped,” he said as they walked down the hall. Isra silently agreed. She could see the entire first floor from the hall. There was a sala to her left, and farther down, a kitchen. To her right was a stairway leading to the second floor, and behind it, almost hidden, a bedroom.

Isra looked around the living room. Though it was much smaller than her parents’ sala back home, it was decorated as though it were a mansion. The floor was covered with a Turkish rug, crimson with a gold pattern in the center. The same pattern was on the burgundy couches, the red throw pillows, and the long, thick curtains lining the windows. A worn leather sofa sat in the corner of the room, as though forgotten, with a shiny gold vase nestled beside it.

“Do you like it?” Adam asked.

“It’s beautiful.”

“I know it’s not bright and airy like the houses back home.” His eyes settled on the windows, which were hidden behind the curtains. “But this is how things are here, what can we do?”

There was something in his voice, and Isra found herself thinking of the day on the balcony, the way his eyes had chased the grapevines, taking in the open scenery. She wondered whether he longed to return to Palestine, whether he wanted to move back home one day.

“Do you miss home?” The sound of her voice startled her, and she dropped her eyes to the floor.

“Yes,” Adam said. “I do.”

Isra looked up to see that he was still staring at the curtains. “Would you ever move back?” she asked.

“Maybe one day,” he said. “If things got better.” He turned away and walked down the hall. Isra followed.

“My parents stay here on the first floor,” Adam said, pointing to the bedroom. “Sarah and my brothers sleep upstairs.”

“Where will we stay?” she asked, hoping her bedroom had a window.

He pointed to a closed door down the hallway. “Downstairs.”

Adam opened the door and signaled her to go down. She did, all the while wondering how they could live in a basement. If there was barely enough light upstairs, what would the basement be like? She peered down the shallow steps. At once, she was overwhelmed with darkness. She put both hands in front of her and descended, the light cast from the doorway fading with each step. She reached the bottom of the stairs and fumbled against the wall in search of a light switch. Cold crept through her fingertips until she found it and flicked it on.

A large, gold mirror hung on the wall directly in front of her. It seemed odd that anyone should place a mirror in such a dreary, uninhabited place. What good was a mirror in the middle of the dark with no light to reflect?

She entered the first room of the basement, surveying the dim space. The room was narrow and empty—four gray walls, bare with the exception of a window to her left and, in the center of the wall ahead, a closed door. Isra opened it to find another room, slightly larger than the first and furnished with a queen-size bed, a small dresser, and a large mirror. Beside the mirror was a small closet, and beside that, a doorway that led to a bathroom. This would be their bedroom, Isra knew. It didn’t have any windows.

She studied her reflection in the mirror. Her face looked dull and gray in the fluorescent light, and she stared at her small, weak frame. She saw a girl who should’ve kicked and screamed as her mother tightened her wedding gown, should’ve begged and hollered as her father secured her in the taxicab to the airport. But she was a coward. She turned away. This is the only familiar face I’ll ever see again, Isra thought. And she couldn’t stand the sight of it.

Upstairs, the earthy smell of sage filled the kitchen. Fareeda was brewing a kettle of chai. She stood over the stove, back hunched, staring absently at the steam. Watching her, Isra found herself thinking of the maramiya plant in her mother’s garden, how Mama would cut off a few leaves every morning to brew in their chai because it helped with Yacob’s indigestion. Isra wondered if Fareeda grew a maramiya plant, too, or if she used dried sage from the market instead.

“Can I help you with something, hamati?” Isra asked as she walked over to the stove. It was the first time she had called Fareeda mother-in-law.

“No, no, no,” Fareeda said, shaking her head. “Don’t call me hamati. Call me Fareeda.”

Growing up, Isra had never heard a married woman called by her first name. Her mother was always referred to as Umm Waleed, mother of her eldest son Waleed, and never Sawsan. Even her aunt Widad, who had never borne a son, was not called by her first name. People called her Mart Jamal, Jamal’s wife.

“I don’t like that word,” Fareeda said, reading the confusion on her face. “It makes me feel old.”

Isra smiled, resting her eyes on the boiling tea.

“Why don’t you set the sufra?” Fareeda said. “I’m making us something to eat.”

“Where’s Adam?”

“He left for work.”

“Oh.” Isra had expected him to stay home today, to take her for a walk around the neighborhood perhaps, introduce her to Brooklyn. Who went to work the day after his wedding?

“He had to run an errand for his father,” Fareeda said. “He’ll be home soon.”

Why couldn’t his brothers run the errand instead? Isra wanted to ask, but she was afraid of saying the wrong thing. She cleared her throat and said, “Did Omar and Ali go with him?”

“I have no idea where they went,” Fareeda said. “Boys are a handful, going and coming as they please. They’re not like girls. You can’t control them.” She handed Isra a stack of plates. “I’m sure you know—you have brothers.”

Isra smiled weakly. “I do.”

“Sarah!” Fareeda called out.

Sarah was upstairs in her bedroom. “Yes, Mama?” she called back.

“Come down here and help Isra set the sufra!” Fareeda said. She turned to Isra. “I don’t want her thinking she’s excused from her chores now that you’re here. That’s how trouble starts.”

“Does she have a lot of chores?” Isra asked.

“Of course,” Fareeda said, looking up to find Sarah at the doorway. “She’s eleven years old, practically a woman. Why, when I was her age, my mother didn’t even have to lift a finger. I was rolling pots of stuffed grape leaves and kneading dough for the entire family.”

“That’s because you didn’t go to school, Mama,” Sarah said. “You had time to do those things. I have homework to catch up on.”

“Your homework can wait,” Fareeda said, handing her the ibrik of chai. “Pour some tea and hurry.”

Sarah poured tea into four glass cups. Isra noticed that she didn’t hurry like Fareeda had asked.

“Is the chai ready?” A man’s voice.

Isra turned to find Khaled in the doorway. She took a good look at him. His hair was thick and silver, his yellow skin wrinkled. He wouldn’t meet her eyes, and she wondered if he was uncomfortable because she wasn’t wearing her hijab. But she didn’t have to wear it in front of him. He was her father-in-law, which, according to Islamic law, made him mahram, like her own father.

“How do you like the neighborhood, Isra?” Khaled said, scanning the sufra. Despite his faded features and the iron-colored hair across his jaw, it was easy to see he had been handsome as a young man.

“It’s beautiful, ami,” Isra said, wondering if perhaps calling him father-in-law would irritate him the way it had Fareeda.

Fareeda looked at her husband and grinned. “You’re ‘ami’ now, you old man!”

“You’re no young damsel yourself,” he said with a smile. “Come on.” He signaled them to sit down. “Let’s eat.”

Isra had never seen so much food on one sufra. Hummus topped with ground beef and pine nuts. Fried halloumi cheese. Scrambled eggs. Falafel. Green and black olives. Labne and za’atar. Fresh pita bread. Even during Ramadan, when Mama made all their favorite meals and Yacob splurged and bought them meat, the food was never this plentiful. The steam of each dish intertwined with the next until the room smelled like home.