полная версия

полная версияGiotto and his works in Padua

XXI.

THE YOUNG CHRIST IN THE TEMPLE

This composition has suffered so grievously by time, that even the portions of it which remain are seen to the greatest disadvantage. Little more than various conditions of scar and stain can be now traced, where were once the draperies of the figures in the shade, and the suspended garland and arches on the right hand of the spectator; and in endeavouring not to represent more than there is authority for, the draughtsman and engraver have necessarily produced a less satisfactory plate than most others of the series. But Giotto has also himself fallen considerably below his usual standard. The faces appear to be cold and hard; and the attitudes are as little graceful as expressive either of attention or surprise. The Madonna's action, stretching her arms to embrace her Son, is pretty; but, on the whole, the picture has no value; and this is the more remarkable, as there were fewer precedents of treatment in this case than in any of the others; and it might have been anticipated that Giotto would have put himself to some pains when the field of thought was comparatively new. The subject of Christ teaching in the Temple rarely occurs in manuscripts; but all the others were perpetually repeated in the service-books of the period.

XXII.

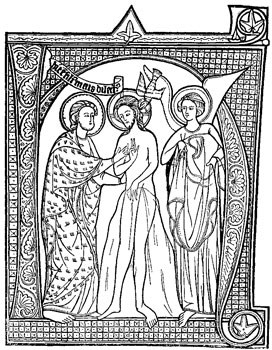

THE BAPTISM OF CHRIST

This is a more interesting work than the last; but it is also gravely and strangely deficient in power of entering into the subject; and this, I think, is common with nearly all efforts that have hitherto been made at its representation. I have never seen a picture of the Baptism, by any painter whatever, which was not below the average power of the painter; and in this conception of Giotto's, the humility of St. John is entirely unexpressed, and the gesture of Christ has hardly any meaning: it neither is in harmony with the words, "Suffer it to be so now," which must have been uttered before the moment of actual baptism, nor does it in the slightest degree indicate the sense in the Redeemer of now entering upon the great work of His ministry. In the earlier representations of the subject, the humility of St. John is never lost sight of; there will be seen, for instance, an effort at expressing it by the slightly stooping attitude and bent knee, even in the very rude design given in outline on the opposite page. I have thought it worth while to set before the reader in this outline one example of the sort of traditional representations which were current throughout Christendom before Giotto arose. This instance is taken from a large choir-book, probably of French, certainly of Northern execution, towards the close of the thirteenth century;22 and it is a very fair average example of the manner of design in the illuminated work of the period. The introduction of the scroll, with the legend, "This is My beloved Son," is both more true to the scriptural words, "Lo, a voice from heaven," and more reverent, than Giotto's introduction of the visible figure, as a type of the First Person of the Trinity. The boldness with which this type is introduced increases precisely as the religious sentiment of art decreases; in the fifteenth century it becomes utterly revolting.

I have given this woodcut for another reason also: to explain more clearly the mode in which Giotto deduced the strange form which he has given to the stream of the Jordan. In the earlier Northern works it is merely a green wave, rising to the Saviour's waist, as seen in the woodcut. Giotto, for the sake of getting standing-ground for his figures, gives shores to this wave, retaining its swelling form in the centre,—a very painful and unsuccessful attempt at reconciling typical drawing with laws of perspective. Or perhaps it is less to be regarded as an effort at progress, than as an awkward combination of the Eastern and Western types of the Jordan. In the difference between these types there is matter of some interest. Lord Lindsay, who merely characterises this work of Giotto's as "the Byzantine composition," thus describes the usual Byzantine manner of representing the Baptism:

"The Saviour stands immersed to the middle in Jordan (flowing between two deep and rocky banks), on one of which stands St. John, pouring the water on His head, and on the other two angels hold His robes. The Holy Spirit descends upon Him as a dove, in a stream of light, from God the Father, usually represented by a hand from Heaven. Two of John's disciples stand behind him as spectators. Frequently the river-god of Jordan reclines with his oars in the corner.... In the Baptistery at Ravenna, the rope is supported, not by an angel, but by the river-deity Jordann (Iordanes?), who holds in his left hand a reed as his sceptre."

Now in this mode of representing rivers there is something more than the mere Pagan tradition lingering through the wrecks of the Eastern Empire. A river, in the East and South, is necessarily recognised more distinctly as a beneficent power than in the West and North. The narrowest and feeblest stream is felt to have an influence on the life of mankind; and is counted among the possessions, or honoured among the deities, of the people who dwell beside it. Hence the importance given, in the Byzantine compositions, to the name and specialty of the Jordan stream. In the North such peculiar definiteness and importance can never be attached to the name of any single fountain. Water, in its various forms of streamlet, rain, or river, is felt as an universal gift of heaven, not as an inheritance of a particular spot of earth. Hence, with the Gothic artists generally, the personality of the Jordan is lost in the green and nameless wave; and the simple rite of the Baptism is dwelt upon, without endeavouring, as Giotto has done, to draw the attention to the rocky shores of Bethabara and Ænon, or to the fact that "there was much water there."

XXIII.

THE MARRIAGE IN CANA

It is strange that the sweet significance of this first of the miracles should have been lost sight of by nearly all artists after Giotto; and that no effort was made by them to conceive the circumstances of it in simplicity. The poverty of the family in which the marriage took place,—proved sufficiently by the fact that a carpenter's wife not only was asked as a chief guest, but even had authority over the servants,—is shown further to have been distressful, or at least embarrassed, poverty by their want of wine on such an occasion. It was not certainly to remedy an accident of careless provision, but to supply a need sorrowfully betraying the narrow circumstances of His hosts, that our Lord wrought the beginning of miracles. Many mystic meanings have been sought in the act, which, though there is no need to deny, there is little evidence to certify: but we may joyfully accept, as its first indisputable meaning, that of simple kindness; the wine being provided here, when needed, as the bread and fish were afterwards for the hungry multitudes. The whole value of the miracle, in its serviceable tenderness, is at once effaced when the marriage is supposed, as by Veronese and other artists of later times, to have taken place at the house of a rich man. For the rest, Giotto sufficiently implies, by the lifted hand of the Madonna, and the action of the fingers of the bridegroom, as if they held sacramental bread, that there lay a deeper meaning under the miracle for those who could accept it. How all miracle is accepted by common humanity, he has also shown in the figure of the ruler of the feast, drinking. This unregarding forgetfulness of present spiritual power is similarly marked by Veronese, by placing the figure of a fool with his bauble immediately underneath that of Christ, and by making a cat play with her shadow in one of the wine-vases.

It is to be remembered, however, in examining all pictures of this subject, that the miracle was not made manifest to all the guests;—to none indeed, seemingly, except Christ's own disciples: the ruler of the feast, and probably most of those present (except the servants who drew the water), knew or observed nothing of what was passing, and merely thought the good wine had been "kept until now."

XXIV.

THE RAISING OF LAZARUS

In consequence of the intermediate position which Giotto occupies between the Byzantine and Naturalist schools, two relations of treatment are to be generally noted in his work. As compared with the Byzantines, he is a realist, whose power consists in the introduction of living character and various incidents, modifying the formerly received Byzantine symbols. So far as he has to do this, he is a realist of the purest kind, endeavoring always to conceive events precisely as they were likely to have happened; not to idealise them into forms artfully impressive to the spectator. But in so far as he was compelled to retain, or did not wish to reject, the figurative character of the Byzantine symbols, he stands opposed to succeeding realists, in the quantity of meaning which probably lies hidden in any composition, as well as in the simplicity with which he will probably treat it, in order to enforce or guide to this meaning: the figures being often letters of a hieroglyphic, which he will not multiply, lest he should lose in force of suggestion what he gained in dramatic interest.

None of the compositions display more clearly this typical and reflective character than that of the Raising of Lazarus. Later designers dwell on vulgar conditions of wonder or horror, such as they could conceive likely to attend the resuscitation of a corpse; but with Giotto the physical reanimation is the type of a spiritual one, and, though shown to be miraculous, is yet in all its deeper aspects unperturbed, and calm in awfulness. It is also visibly gradual. "His face was bound about with a napkin." The nearest Apostle has withdrawn the covering from the face, and looks for the command which shall restore it from wasted corruption, and sealed blindness, to living power and light.

Nor is it, I believe, without meaning, that the two Apostles, if indeed they are intended for Apostles, who stand at Lazarus' side, wear a different dress from those who follow Christ. I suppose them to be intended for images of the Christian and Jewish Churches in their ministration to the dead soul: the one removing its bonds, but looking to Christ for the word and power of life; the other inactive and helpless—the veil upon its face—in dread; while the principal figure fulfils the order it receives in fearless simplicity.

XXV.

THE ENTRY INTO JERUSALEM

This design suffers much from loss of colour in translation. Its decorative effect depends on the deep blue ground, relieving the delicate foliage and the local colours of dresses and architecture. It is also one of those which are most directly opposed to modern feeling: the sympathy of the spectator with the passion of the crowd being somewhat rudely checked by the grotesque action of two of the foremost figures. We ought, however, rather to envy the deep seriousness which could not be moved from dwelling on the real power of the scene by any ungracefulness or familiarity of circumstance. Among men whose minds are rightly toned, nothing is ludicrous: it must, if an act, be either right or wrong, noble or base; if a thing seen, it must either be ugly or beautiful: and what is either wrong or deformed is not, among noble persons, in anywise subject for laughter; but, in the precise degree of its wrongness or deformity, a subject of horror. All perception of what, in the modern European mind, falls under the general head of the ludicrous, is either childish or profane; often healthy, as indicative of vigorous animal life, but always degraded in its relation to manly conditions of thought. It has a secondary use in its power of detecting vulgar imposture; but it only obtains this power by denying the highest truths.

XXVI.

THE EXPULSION FROM THE TEMPLE

More properly, the Expulsion from the outer Court of the Temple (Court of Gentiles), as Giotto has indicated by placing the porch of the Temple itself in the background.

The design shows, as clearly as that of the Massacre of the Innocents, Giotto's want of power, and partly of desire, to represent rapid or forceful action. The raising of the right hand, not holding any scourge, resembles the action afterwards adopted by Oreagna, and finally by Michael Angelo in his Last Judgment: and my belief is, that Giotto considered this act of Christ's as partly typical of the final judgment, the Pharisees being placed on the left hand, and the disciples on the right. From the faded remains of the fresco, the draughtsman could not determine what animals are intended by those on the left hand. But the most curious incident (so far as I know, found only in this design of the Expulsion, no subsequent painter repeating it), is the sheltering of the two children, one of them carrying a dove, under the arm and cloak of two disciples. Many meanings might easily be suggested in this; but I see no evidence for the adoption of any distinct one.

XXVII.

THE HIRING OF JUDAS

The only point of material interest presented by this design is the decrepit and distorted shadow of the demon, respecting which it may be well to remind the reader that all the great Italian thinkers concurred in assuming decrepitude or disease, as well as ugliness, to be a characteristic of all natures of evil. Whatever the extent of the power granted to evil spirits, it was always abominable and contemptible; no element of beauty or heroism was ever allowed to remain, however obscured, in the aspect of a fallen angel. Also, the demoniacal nature was shown in acts of betrayal, torture, or wanton hostility; never in valiancy or perseverance of contest. I recollect no mediæval demon who shows as much insulting, resisting, or contending power as Bunyan's Apollyon. They can only cheat, undermine, and mock; never overthrow. Judas, as we should naturally anticipate, has not in this scene the nimbus of an Apostle; yet we shall find it restored to him in the next design. We shall discover the reason of this only by a careful consideration of the meaning of that fresco.

XXVIII.

THE LAST SUPPER

I have not examined the original fresco with care enough to be able to say whether the uninteresting quietness of its design is redeemed by more than ordinary attention to expression; it is one of the least attractive subjects in the Arena Chapel, and always sure to be passed over in any general observation of the series: nevertheless, however unfavourably it may at first contrast with the designs of later masters, and especially with Leonardo's, the reader should not fail to observe that Giotto's aim, had it been successful, was the higher of the two, as giving truer rendering of the probable fact. There is no distinct evidence, in the sacred text, of the annunciation of coming treachery having produced among the disciples the violent surprise and agitation represented by Leonardo. Naturally, they would not at first understand what was meant. They knew nothing distinctly of the machinations of the priests; and so little of the character or purposes of Judas, that even after he had received the sop which was to point him out to the others as false;—and after they had heard the injunction, "That thou doest, do quickly,"—the other disciples had still no conception of the significance, either of the saying, or the act: they thought that Christ meant he was to buy something for the feast. Nay, Judas himself, so far from starting, as a convicted traitor, and thereby betraying himself, as in Leonardo's picture, had not, when Christ's first words were uttered, any immediately active intention formed. The devil had not entered into him until he received the sop. The passage in St. John's account is a curious one, and little noticed; but it marks very distinctly the paralysed state of the man's mind. He had talked with the priests, covenanted with them, and even sought opportunity to bring Jesus into their hands; but while such opportunity was wanting, the act had never presented itself fully to him for adoption or rejection. He had toyed with it, dreamed over it, hesitated, and procrastinated over it, as a stupid and cowardly person would, such as traitors are apt to be. But the way of retreat was yet open; the conquest of the temper not complete. Only after receiving the sop the idea finally presented itself clearly, and was accepted, "To-night, while He is in the garden, I can do it; and I will." And Giotto has indicated this distinctly by giving Judas still the Apostle's nimbus, both in this subject and in that of the Washing of the Feet; while it is taken away in the previous subject of the Hiring, and the following one of the Seizure: thus it fluctuates, expires, and reillumines itself, until his fall is consummated. This being the general state of the Apostles' knowledge, the words, "One of you shall betray me," would excite no feeling in their minds correspondent to that with which we now read the prophetic sentence. What this "giving up" of their Master meant became a question of bitter and self-searching thought with them,—gradually of intense sorrow and questioning. But had they understood it in the sense we now understand it, they would never have each asked, "Lord, is it I?" Peter believed himself incapable even of denying Christ; and of giving him up to death for money, every one of his true disciples knew themselves incapable; the thought never occurred to them. In slowly-increasing wonder and sorrow (ηρξαντο λυπεισθαι, Mark xiv. 19), not knowing what was meant, they asked one by one, with pauses between, "Is it I?" and another, "Is it I?" and this so quietly and timidly that the one who was lying on Christ's breast never stirred from his place; and Peter, afraid to speak, signed to him to ask who it was. One further circumstance, showing that this was the real state of their minds, we shall find Giotto take cognisance of in the next fresco.

XXIX.

THE WASHING OF THE FEET

In this design, it will be observed, there are still the twelve disciples, and the nimbus is yet given to Judas (though, as it were, setting, his face not being seen).

Considering the deep interest and importance of every circumstance of the Last Supper, I cannot understand how preachers and commentators pass by the difficulty of clearly understanding the periods indicated in St. John's account of it. It seems that Christ must have risen while they were still eating, must have washed their feet as they sate or reclined at the table, just as the Magdalen had washed His own feet in the Pharisee's house; that, this done, He returned to the table, and the disciples continuing to eat, presently gave the sop to Judas. For St. John says, that he having received the sop, went immediately out; yet that Christ had washed his feet is certain, from the words, "Ye are clean, but not all." Whatever view the reader may, on deliberation, choose to accept, Giotto's is clear, namely, that though not cleansed by the baptism, Judas was yet capable of being cleansed. The devil had not entered into him at the time of the washing of the feet, and he retains the sign of an Apostle.

The composition is one of the most beautiful of the series, especially owing to the submissive grace of the two standing figures.

XXX.

THE KISS OF JUDAS

For the first time we have Giotto's idea of the face of the traitor clearly shown. It is not, I think, traceable through any of the previous series; and it has often surprised me to observe how impossible it was in the works of almost any of the sacred painters to determine by the mere cast of feature which was meant for the false Apostle. Here, however, Giotto's theory of physiognomy, and together with it his idea of the character of Judas, are perceivable enough. It is evident that he looks upon Judas mainly as a sensual dullard, and foul-brained fool; a man in no respect exalted in bad eminence of treachery above the mass of common traitors, but merely a distinct type of the eternal treachery to good, in vulgar men, which stoops beneath, and opposes in its appointed measure, the life and efforts of all noble persons, their natural enemies in this world; as the slime lies under a clear stream running through an earthy meadow. Our careless and thoughtless English use of the word into which the Greek "Diabolos" has been shortened, blinds us in general to the meaning of "Deviltry," which, in its essence, is nothing else than slander, or traitorhood;—the accusing and giving up of good. In particular it has blinded us to the meaning of Christ's words, "Have not I chosen you twelve, and one of you is a traitor and accuser?" and led us to think that the "one of you is a devil" indicated some greater than human wickedness in Judas; whereas the practical meaning of the entire fact of Judas' ministry and fall is, that out of any twelve men chosen for the forwarding of any purpose,—or, much more, out of any twelve men we meet,—one, probably, is or will be a Judas.

The modern German renderings of all the scenes of Christ's life in which the traitor is conspicuous are very curious in their vulgar misunderstanding of the history, and their consequent endeavours to represent Judas as more diabolic than selfish, treacherous, and stupid men are in all their generations. They paint him usually projected against strong effects of light, in lurid chiaroscuro;—enlarging the whites of his eyes, and making him frown, grin, and gnash his teeth on all occasions, so as to appear among the other Apostles invariably in the aspect of a Gorgon.

How much more deeply Giotto has fathomed the fact, I believe all men will admit who have sufficient purity and abhorrence of falsehood to recognise it in its daily presence, and who know how the devil's strongest work is done for him by men who are too bestial to understand what they betray.

XXXI.

CHRIST BEFORE CAIAPHAS

Little is to be observed in this design of any distinctive merit; it is only a somewhat completer version of the ordinary representation given in illuminated missals and other conventual work, suggesting, as if they had happened at the same moment, the answer, "If I have spoken evil, bear witness of the evil," and the accusation of blasphemy which causes the high-priest to rend his clothes.

Apparently distrustful of his power of obtaining interest of a higher kind, Giotto has treated the enrichments more carefully than usual, down even to the steps of the high-priest's seat. The torch and barred shutters conspicuously indicate its being now dead of night. That the torch is darker than the chamber, if not an error in the drawing, is probably the consequence of a darkening alteration in the yellow colours used for the flame.

XXXII.

THE SCOURGING OF CHRIST

It is characteristic of Giotto's rational and human view of all subjects admitting such aspect, that he has insisted here chiefly on the dejection and humiliation of Christ, making no attempt to suggest to the spectator any other divinity than that of patience made perfect through suffering. Angelico's conception of the same subject is higher and more mystical. He takes the moment when Christ is blindfolded, and exaggerates almost into monstrosity the vileness of feature and bitterness of sneer in the questioners, "Prophesy unto us, who is he that smote thee;" but the bearing of the person of Christ is entirely calm and unmoved; and his eyes, open, are seen through the binding veil, indicating the ceaseless omniscience.

This mystical rendering is, again, rejected by the later realistic painters; but while the earlier designers, with Giotto at their head, dwelt chiefly on the humiliation and the mockery, later painters dwelt on the physical pain. In Titian's great picture of this subject in the Louvre, one of the executioners is thrusting the thorn-crown down upon the brow with his rod, and the action of Christ is that of a person suffering extreme physical agony.

No representations of the scene exist, to my knowledge, in which the mockery is either sustained with indifference, or rebuked by any stern or appealing expression of feature; yet one of these two forms of endurance would appear, to a modern habit of thought, the most natural and probable.