полная версия

полная версияMemoir, Correspondence, And Miscellanies, From The Papers Of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 4

In this state of things, we are called on to add ninety millions more to the circulation. Proceeding in this career, it is infallible, that we must end where the revolutionary paper ended. Two hundred millions was the whole amount of all the emissions of the old Congress, at which point their bills ceased to circulate. We are now at that sum; but with treble the population, and of course a longer tether. Our depreciation is, as yet, but at about two for one. Owing to the support its credit receives from the small reservoirs of specie in the vaults of the banks, it is impossible to say at what point their notes will stop. Nothing is necessary to effect it but a general alarm; and that may take place whenever the public shall begin to reflect on, and perceive, the impossibility that the banks should repay this sum. At present, caution is inspired no farther than to keep prudent men from selling property on long payments. Let us suppose the panic to arise at three hundred millions, a point to which every session of the legislatures hastens us by long strides. Nobody dreams that they would have three hundred millions of specie to satisfy the holders of their notes. Were they even to stop now, no one supposes they have two hundred millions in cash, or even the sixty-six and two-thirds millions, to which amount alone the law obliges them to repay. One hundred and thirty-three and one-third millions of loss, then, is thrown on the public by law; and as to the sixty-six and two-thirds, which they are legally bound to pay, and ought to have in their vaults, every one knows there is no such amount of cash in the United States, and what would be the course with what they really have there? Their notes are refused. Cash is called for. The inhabitants of the banking towns will get what is in the vaults, until a few banks declare their insolvency; when, the general crush becoming evident, the others will withdraw even the cash they have, declare their bankruptcy at once, and leave an empty house and empty coffers for the holders of their notes. In this scramble of creditors, the country gets nothing, the towns but little. What are they to do? Bring suits? A million of creditors bring a million of suits against John Nokes and Robert Styles, wheresoever to be found? All nonsense. The loss is total. And a sum is thus swindled from our citizens, of seven times the amount of the real debt, and four times that of the factitious one of the United States, at the close of the war. All this they will justly charge on their legislatures; but this will be poor satisfaction for the two or three hundred millions they will have lost. It is time, then, for the public functionaries to look to this. Perhaps it may not be too late. Perhaps, by giving time to the banks, they may call in and pay off their paper by degrees. But no remedy is ever to be expected while it rests with the State legislatures. Personal motives can be excited through so many avenues to their will, that, in their hands, it will continue to go on from bad to worse, until the catastrophe overwhelms us. I still believe, however, that on proper representations of the subject, a great proportion of these legislatures would cede to Congress their power of establishing banks, saving the charter rights already granted. And this should be asked, not by way of amendment to the constitution, because until three fourths should consent, nothing could be done; but accepted from them one by one, singly, as their consent might be obtained. Any single State, even if no other should come into the measure, would find its interest in arresting foreign bank-paper immediately, and its own by degrees. Specie would flow in on them as paper disappeared. Their own banks would call in and pay off their notes gradually, and their constituents would thus be saved from the general wreck. Should the greater part of the States concede, as is expected, their power over banks to Congress, besides insuring their own safety, the paper of the non-conceding States might be so checked and circumscribed, by prohibiting its receipt in any of the conceding States, and even in the non-conceding as to duties, taxes, judgments, or other demands of the United States, or of the citizens of other States, that it would soon die of itself, and the medium of gold and silver be universally restored. This is what ought to be done. But it will not be done. Carthago non delebitur. The overbearing clamor of merchants, speculators, and projectors, will drive us before them with our eyes open, until, as in France, under the Mississippi bubble, our citizens will be overtaken by the crash of this baseless fabric, without other satisfaction than that of execrations on the heads of those functionaries, who, from ignorance, pusillanimity, or corruption, have betrayed the fruits of their industry into the hands of projectors and swindlers.

When I speak comparatively of the paper emissions of the old Congress and the present banks, let it not be imagined that I cover them under the same mantle. The object of the former was a holy one; for if ever there was a holy war, it was that which saved our liberties and gave us independence. The object of the latter, is to enrich swindlers at the expense of the honest and industrious part of the nation.

The sum of what has been said is, that pretermitting the constitutional question on the authority of Congress, and considering this application on the grounds of reason alone, it would be best that our medium should be so proportioned to our produce, as to be on a par with that of the countries with which we trade, and whose medium is in a sound state: that specie is the most perfect medium, because it will preserve its own level; because, having intrinsic and universal value, it can never die in our hands, and it is the surest resource of reliance in time of war: that the trifling economy of paper, as a cheaper medium, or its convenience for transmission, weighs nothing in opposition to the advantages of the precious metals: that it is liable to be abused, has been, is, and for ever will be abused, in every country in which it is permitted; that it is already at a term of abuse in these States, which has never been reached by any other nation, France excepted, whose dreadful catastrophe should be a warning against the instrument which produced it: that we are already at ten or twenty times the due quantity of medium; insomuch, that no man knows what his property is now worth, because it is bloating while he is calculating; and still less what it will be worth when the medium shall be relieved from its present dropsical state: and that it is a palpable falsehood to say we can have specie for our paper whenever demanded. Instead, then, of yielding to the cries of scarcity of medium set up by speculators, projectors, and commercial gamblers, no endeavors should be spared to begin the work of reducing it by such gradual means as may give time to private fortunes to preserve their poise, and settle down with the subsiding medium; and that, for this purpose, the States should be urged to concede to the General Government, with a saving of chartered rights, the exclusive power of establishing banks of discount for paper.

To the existence of banks of discount for cash, as on the continent of Europe, there can be no objection, because there can be no danger of abuse, and they are a convenience both to merchants and individuals. I think they should even be encouraged, by allowing them a larger than legal, interest on short discounts, and tapering thence, in proportion as the term of discount is lengthened, down to legal interest on those of a year or more. Even banks of deposite, where cash should be lodged, and a paper acknowledgment taken out as its representative, entitled to a return of the cash on demand, would be convenient for remittances, travelling persons, he. But, liable as its cash would be to be pilfered and robbed, and its paper to be fraudulently re-issued, or issued without deposite, it would require skilful and strict regulation. This would differ from the bank of Amsterdam, in the circumstance that the cash could be re-demanded on returning the note.

When I commenced this letter to you, my dear Sir, on Mr. Law’s memorial, I expected a short one would have answered that. But as I advanced, the subject branched itself before me into so many collateral questions, that even the rapid views I have taken of each have swelled the volume of my letter beyond my expectations, and, I fear, beyond your patience. Yet on a revisal of it, I find no part which has not so much bearing on the subject as to be worth merely the time of perusal. I leave it then as it is; and will add only the assurances of my constant and affectionate esteem and respect.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER CXIV.—TO JOHN ADAMS, October 13, 1813

TO JOHN ADAMS.

Monticello, October 13, 1813.

Dear Sir,

Since mine of August the 22nd, I have received your favors of August the 16th, September the 2nd, 14th, 15th, and, and Mrs. Adams’s, of September the 20th. I now send you, according to your request, a copy of the syllabus. To fill up this skeleton with arteries, with veins, with nerves, muscles, and flesh, is really beyond my time and information. Whoever could undertake it, would find great aid in Enfield’s judicious abridgment of Brucker’s History of Philosophy, in which he has reduced five or six quarto volumes, of one thousand pages each of Latin closely printed, to two moderate octavos of English open type.

To compare the morals of the Old, with those of the New Testament, would require an attentive study of the former, a search through all its books for its precepts, and through all its history for its practices, and the principles they prove. As commentaries, too, on these, the philosophy of the Hebrews must be inquired into, their Mishna, their Gemara, Cabbala, Jezirah, Sonar, Cosri, and their Talmud, must be examined and understood, in order to do them full justice. Brucker, it would seem, has gone deeply into these repositories of their ethics, and Enfield his epitomizer, concludes in these words. ‘Ethics were so little understood among the Jews, that, in their whole compilation called the Talmud, there is only one treatise on moral subjects. Their books of morals chiefly consisted in a minute enumeration of duties. From the law of Moses were deduced six hundred and thirteen precepts, which were divided into two classes, affirmative and negative, two hundred and forty-eight in the former, and three hundred and sixty-five in the latter. It may serve to give the reader some idea of the low state of moral philosophy among the Jews in the middle age, to add, that of the two hundred and forty-eight affirmative precepts, only three were considered as obligatory upon women; and that, in order to obtain salvation, it was judged sufficient to fulfil any one single law in the hour of death; the observance of the rest being deemed necessary, only to increase the felicity of the future life. What a wretched depravity of sentiment and manners must have prevailed, before such corrupt maxims could have obtained credit! It is impossible to collect from these writings a consistent series of moral doctrine. (Enfield, B. 4. chap. 3.) It was the reformation of this wretched depravity of morals which Jesus undertook. In extracting the pure principles which he taught, we should have to strip off the artificial vestments in which they have been muffled by priests who have travestied them into various forms, as instruments of riches and power to themselves. We must dismiss the Platonists and Plotinists, the Stagyrites and Gamalielites, the Eclectics, the Gnostics and Scholastics, their essences and emanations, their Logos and Demiurgos, Æons, and Daemons, male and female, with a long train of &c. &c. &c. or, shall I say at once, of nonsense. We must reduce our volume to the simple evangelists, select, even from them, the very words only of Jesus, paring off the amphiboligisms into which they have been led, by forgetting often, or not understanding, what had fallen from him, by giving their own misconceptions as his dicta, and expressing unintelligibly for others what they had not understood themselves. There will be found remaining the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man. I have performed this operation for my own use, by cutting verse by verse out of the printed book, and arranging the matter which is evidently his, and which is as easily distinguishable as diamonds, in a dunghill. The result is an octavo of forty-six pages, of pure and unsophisticated doctrines, such as were professed and acted on by the unlettered Apostles, the Apostolic Fathers, and the Christians, of the first century. Their Platonizing successors, indeed, in after times, in order to legitimate the corruptions which they had incorporated into the doctrines of Jesus, found it necessary to disavow the primitive Christians, who had taken their principles from the mouth of Jesus himself, of his Apostles, and the Fathers cotemporary with them. They excommunicated their followers as heretics, branding them with the opprobrious name of Ebionites and Beggars. For a comparison of the Grecian philosophy with that of Jesus, materials might be largely drawn from the same source. Enfield gives a history and detailed account of the opinions and principles of the different sects. These relate to the Gods, their natures, grades, places, and powers; the demi-Gods and Demons, and their agency with man; the universe, its structure, extent, and duration; the origin of things from the elements of fire, water, air, and earth; the human soul, its essence and derivation; the summum bonum, and finis bonorum; with a thousand idle dreams and fancies on these and other subjects, the knowledge of which is withheld from man; leaving but a short chapter for his moral duties, and the principal section of that given to what he owes himself, to precepts for rendering him impassible, and unassailable by the evils of life, and for preserving his mind in a state of constant serenity.

Such a canvass is too broad for the age of seventy, and especially of one whose chief occupations have been in the practical business of life. We must leave, therefore, to others, younger and more learned than we are, to prepare this euthanasia for Platonic Christianity, and its restoration to the primitive simplicity of its founder. I think you give a just outline of the theism of the three religions, when you say that the principle of the Hebrew was the fear, of the Gentile the honor, and of the Christian the love of God.

An expression in your letter of September the 14th, that ‘the human understanding is a revelation from its maker,’ gives the best solution that I believe can be given of the question, ‘What did Socrates mean by his Daemon?’ He was too wise to believe, and too honest to pretend, that he had real and familiar converse with a superior and invisible being. He probably considered the suggestions of his conscience, or reason, as revelations, or inspirations from the Supreme mind, bestowed, on important occasions, by a special superintending providence.

I acknowledge all the merit of the hymn of Cleanthes to Jupiter, which you ascribe to it. It is as highly sublime as a chaste and correct imagination can permit itself to go. Yet in the contemplation of a being so superlative, the hyperbolic flights of the Psalmist may often be followed with approbation, even with rapture; and I have no hesitation in giving him the palm over all the hymnists of every language, and of every time. Turn to the 148th psalm in Brady and Tate’s version. Have such conceptions been ever before expressed? Their version of the 15th psalm is more to be esteemed for its pithiness than its poetry. Even Sternhold, the leaden Sternhold, kindles, in a single instance, with the sublimity of his original, and expresses the majesty of God descending on the earth, in terms not unworthy of the subject.

The Latin versions of this passage by Buchanan and by Johnston, are but mediocres. But the Greek of Duport is worthy of quotation.

The best collection of these psalms is that of the Octagonian dissenters of Liverpool, in their printed form of prayer; but they are not always the best versions. Indeed, bad is the best of the English versions; not a ray of poetical genius having ever been employed on them. And how much depends on this, may be seen by comparing Brady and Tate’s 15th psalm with Blacklock’s Justum et tenacem propositi virum of Horace, quoted in Hume’s History, Car. 2. ch. 66. A translation of David in this style, or in that of Pompei’s Cleanthes, might give us some idea of the merit of the original. The character, too, of the poetry of these hymns is singular to us; written in monostichs, each divided into strophe and antistrophe, the sentiment of the first member responded with amplification or antithesis in the second.

On the subject of the Postscript of yours of August the 16th and of Mrs. Adams’s letter, I am silent. I know the depth of the affliction it has caused, and can sympathize with it the more sensibly, inasmuch as there is no degree of affliction, produced by the loss of those dear to us, which experience has not taught me to estimate. I have ever found time and silence the only medicine, and these but assuage, they never can suppress, the deep-drawn sigh which recollection for ever brings up, until recollection and life are extinguished together. Ever affectionately yours.

Th: Jefferson.

LETTER CXV.—TO JOHN ADAMS, October 28, 1813

TO JOHN ADAMS.

Monticello, October 28, 1813.

Dear Sir,

According to the reservation between us, of taking up one of the subjects of our correspondence at a time, I turn to your letters of August the 16th and September the 2nd.

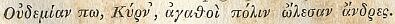

The passage you quote from Theognis, I think has an ethical rather than a political object. The whole piece is a moral exhortation,

and this passage particularly seems to be a reproof to man, who, while with his domestic animals he is curious to improve the race, by employing always the finest male, pays no attention to the improvement of his own race, but intermarries with the vicious, the ugly, or the old, for considerations of wealth or ambition. It is in conformity with the principle adopted afterwards by the Pythagoreans, and expressed by Ocellus in another form;

which, as literally as intelligibility will admit, may be thus translated; ‘Concerning the interprocreation of men, how, and of whom it shall be, in a perfect manner, and according to the laws of modesty and sanctity, conjointly, this is what I think right. First, to lay it down that we do not commix for the sake of pleasure, but of the procreation of children. For the powers, the organs, and desires for coition have not been given by God to man for the sake of pleasure, but for the procreation of the race. For as it were incongruous for a mortal born to partake of divine life, the immortality of the race being taken away, God fulfilled the purpose by making the generations uninterrupted and continuous. This, therefore, we are especially to lay down as a principle, that coition is not for the sake of pleasure.’ But nature, not trusting to this moral and abstract motive, seems to have provided more securely for the perpetuation of the species, by making it the effect of the oestrum implanted in the constitution of both sexes. And not only has the commerce of love been indulged on this unhallowed impulse, but made subservient also to wealth and ambition by marriages, without regard to the beauty, the healthiness, the understanding, or virtue of the subject from which we are to breed. The selecting the best male for a Haram of well chosen females, also, which Theognis seems to recommend from the example of our sheep and asses, would doubtless improve the human, as it does the brute animal, and produce a race of veritable

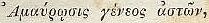

For experience proves, that the moral and physical qualities of man, whether good or evil, are transmissible in a certain degree from father to son. But I suspect that the equal rights of men will rise up against this privileged Solomon and his Haram, and oblige us to continue acquiescence under the

It is probable that our difference of opinion may, in some measure, be produced by a difference of character in those among whom we live. From what I have seen of Massachusetts and Connecticut myself, and still more from what I have heard, and the character given of the former by yourself, (Vol. I, page 111,) who know them so much better, there seems to be in those two States a traditionary reverence for certain families, which has rendered the offices of government nearly hereditary in those families. I presume that from an early period of your history, members of these families happening to possess virtue and talents, have honestly exercised them for the good of the people, and by their services have endeared their names to them. In coupling Connecticut with you, I mean it politically only, not morally. For having made the Bible the common law of their land, they seem to have modeled their morality on the story of Jacob and Laban. But although this hereditary succession to office with you may, in some degree, be founded in real family merit, yet in a much higher degree, it has proceeded from your strict alliance of Church and State. These families are canonized in the eyes of the people on the common principle, ‘You tickle me, and I will tickle you.’ In Virginia, we have nothing of this. Our clergy, before the revolution, having been secured against rivalship by fixed salaries, did not give themselves the trouble of acquiring influence over the people. Of wealth, there were great accumulations in particular families, handed down from generation to generation, under the English law of entails. But the only object of ambition for the wealthy was a seat in the King’s Council. All their court then was paid to the crown and its creatures; and they Philipized in all collisions between the King and the people. Hence they were unpopular; and that unpopularity continues attached to their names. A Randolph, a Carter, or a Burwell must have great personal superiority over a common competitor, to be elected by the people, even at this day. At the first session of our legislature after the Declaration of Independence, we passed a law abolishing entails. And this was followed by one abolishing the privilege of primogeniture, and dividing the lands of intestates equally among all their children, or other representatives. These laws, drawn by myself, laid the axe to the root of pseudo-aristocracy. And had another which I prepared been adopted by the legislature, our work would have been complete. It was a bill for the more general diffusion of learning. This proposed to divide every county into wards of five or six miles square, like your townships; to establish in each ward a free school for reading, writing, and common arithmetic; to provide for the annual selection of the best subjects from these schools, who might receive, at the public expense, a higher degree of education at a district school; and from these district schools to select a certain number of the most promising subjects, to be completed at an University, where all the useful sciences should be taught. Worth and genius would thus have been sought out from every condition of life, and completely prepared by education for defeating the competition of wealth and birth for public trusts. My proposition had, for a further object, to impart to these wards those portions of self-government for which they are best qualified, by confiding to them the care of their poor, their roads, police, elections, the nomination of jurors, administration of justice in small cases, elementary exercises of militia; in short, to have made them little republics, with a warden at the head of each, for all those concerns which, being under their eye, they would better manage than the larger republics of the county or State. A general call of ward-meetings by their wardens on the same day through the State, would at any time produce the genuine sense of the people on any required point, and would enable the State to act in mass, as your people have so often done, and with so much effect, by their town-meetings. The law for religious freedom, which made a part of this system, having put down the aristocracy of the clergy, and restored to the citizen the freedom of the mind, and those of entails and descents nurturing an equality of condition among them, this on education would have raised the mass of the people to the high ground of moral respectability necessary to their own safety, and to orderly government; and would have completed the great object of qualifying them to select the veritable aristoi, for the trusts of government, to the exclusion of the pseudalists: and the same Theognis, who has furnished the epigraphs of your two letters, assures us that