полная версия

полная версияThe Mystery of the Yellow Room

“When I returned to the great gallery,” continued Rouletabille, “I saw no more of Monsieur Robert Darzac, and I was not to see him again until after the tragedy at the Glandier. Mademoiselle was near Mr. Rance, who was talking with much animation, his eyes, during the conversation, glowing with a singular brightness. Mademoiselle Stangerson, I thought, was not even listening to what he was saying, her face expressing perfect indifference. His face was the red face of a drunkard. When Monsieur and Mademoiselle Stangerson left, he went to the bar and remained there. I joined him, and rendered him some little service in the midst of the pressing crowd. He thanked me and told me he was returning to America three days later, that is to say, on the 26th (the day after the crime). I talked with him about Philadelphia; he told me he had lived there for five-and-twenty years, and that it was there he had met the illustrious Professor Stangerson and his daughter. He drank a great deal of champagne, and when I left him he was very nearly drunk.

“Such were my experiences on that evening, and I leave you to imagine what effect the news of the attempted murder of Mademoiselle Stangerson produced on me,—with what force those words pronounced by Monsieur Robert Darzac, ‘Must I commit a crime, then, to win you?’ recurred to me. It was not this phrase, however, that I repeated to him, when we met here at Glandier. The sentence of the presbytery and the bright garden sufficed to open the gate of the chateau. If you ask me if I believe now that Monsieur Darzac is the murderer, I must say I do not. I do not think I ever quite thought that. At the time I could not really think seriously of anything. I had so little evidence to go on. But I needed to have at once the proof that he had not been wounded in the hand.

“When we were alone together, I told him how I had chanced to overhear a part of his conversation with Mademoiselle Stangerson in the garden of the Elysee; and when I repeated to him the words, ‘Must I commit a crime, then, to win you?’ he was greatly troubled, though much less so than he had been by hearing me repeat the phrase about the presbytery. What threw him into a state of real consternation was to learn from me that the day on which he had gone to meet Mademoiselle Stangerson at the Elysee, was the very day on which she had gone to the Post Office for the letter. It was that letter, perhaps, which ended with the words: ‘The presbytery has lost nothing of its charm, nor the garden its brightness.’ My surmise was confirmed by my finding, if you remember, in the ashes of the laboratory, the fragment of paper dated October the 23rd. The letter had been written and withdrawn from the Post Office on the same day.

“There can be no doubt that, on returning from the Elysee that night, Mademoiselle Stangerson had tried to destroy that compromising paper. It was in vain that Monsieur Darzac denied that that letter had anything whatever to do with the crime. I told him that in an affair so filled with mystery as this, he had no right to hide this letter; that I was persuaded it was of considerable importance; that the desperate tone in which Mademoiselle Stangerson had pronounced the prophetic phrase,—that his own tears, and the threat of a crime which he had professed after the letter was read—all these facts tended to leave no room for me to doubt. Monsieur Darzac became more and more agitated, and I determined to take advantage of the effect I had produced on him. ‘You were on the point of being married, Monsieur,’ I said negligently and without looking at him, ‘and suddenly your marriage becomes impossible because of the writer of that letter; because as soon as his letter was read, you spoke of the necessity for a crime to win Mademoiselle Stangerson. Therefore there is someone between you and her—someone who is preventing your marriage with her—someone who has attempted to kill her, so that she should not be able to marry!’ And I concluded with these words: ‘Now, monsieur, you have only to tell me in confidence the name of the murderer!’—The words I had uttered must have struck him ominously, for when I turned my eyes on him, I saw that his face was haggard, the perspiration standing on his forehead, and terror showing in his eyes.

“‘Monsieur,’ he said to me, ‘I am going to ask of you something which may appear insane, but in exchange for which I place my life in your hands. You must not tell the magistrates of what you saw and heard in the garden of the Elysee,—neither to them nor to anybody. I swear to you, that I am innocent, and I know, I feel, that you believe me; but I would rather be taken for the guilty man than see justice go astray on that phrase, “The presbytery has lost nothing of its charm, nor the garden its brightness.” The judges must know nothing about that phrase. All this matter is in your hands. Monsieur, I leave it there; but forget the evening at the Elysee. A hundred other roads are open to you in your search for the criminal. I will open them for you myself. I will help you. Will you take up your quarters here?—You may remain here to do as you please.—Eat—sleep here—watch my actions—the actions of all here. You shall be master of the Glandier, Monsieur; but forget the evening at the Elysee.’”

Rouletabille here paused to take breath. I now understood what had appeared so unexplainable in the demeanour of Monsieur Robert Darzac towards my friend, and the facility with which the young reporter had been able to install himself on the scene of the crime. My curiosity could not fail to be excited by all I had heard. I asked Rouletabille to satisfy it still further. What had happened at the Glandier during the past week?—Had he not told me that there were surface indications against Monsieur Darzac much more terrible than that of the cane found by Larsan?

“Everything seems to be pointing against him,” replied my friend, “and the situation is becoming exceedingly grave. Monsieur Darzac appears not to mind it much; but in that he is wrong. I was interested only in the health of Mademoiselle Stangerson, which was daily improving, when something occurred that is even more mysterious than—than the mystery of The Yellow Room!”

“Impossible!” I cried, “What could be more mysterious than that?”

“Let us first go back to Monsieur Robert Darzac,” said Rouletabille, calming me. “I have said that everything seems to be pointing against him. The marks of the neat boots found by Frederic Larsan appear to be really the footprints of Mademoiselle Stangerson’s fiance. The marks made by the bicycle may have been made by his bicycle. He had usually left it at the chateau; why did he take it to Paris on that particular occasion? Was it because he was not going to return again to the chateau? Was it because, owing to the breaking off of his marriage, his relations with the Stangersons were to cease? All who are interested in the matter affirm that those relations were to continue unchanged.

“Frederic Larsan, however, believes that all relations were at an end. From the day when Monsieur Darzac accompanied Mademoiselle Stangerson to the Grands Magasins de la Louvre until the day after the crime, he had not been at the Glandier. Remember that Mademoiselle Stangerson lost her reticule containing the key with the brass head while she was in his company. From that day to the evening at the Elysee, the Sorbonne professor and Mademoiselle Stangerson did not see one another; but they may have written to each other. Mademoiselle Stangerson went to the Post Office to get a letter, which Larsan says was written by Robert Darzac; for knowing nothing of what had passed at the Elysee, Larsan believes that it was Monsieur Darzac himself who stole the reticule with the key, with the design of forcing her consent, by getting possession of the precious papers of her father—papers which he would have restored to him on condition that the marriage engagement was to be fulfilled.

“All that would have been a very doubtful and almost absurd hypothesis, as Larsan admitted to me, but for another and much graver circumstance. In the first place here is something which I have not been able to explain—Monsieur Darzac had himself, on the 24th, gone to the Post Office to ask for the letter which Mademoiselle had called for and received on the previous evening. The description of the man who made application tallies in every respect with the appearance of Monsieur Darzac, who, in answer to the questions put to him by the examining magistrate, denies that he went to the Post Office. Now even admitting that the letter was written by him—which I do not believe—he knew that Mademoiselle Stangerson had received it, since he had seen it in her hands in the garden at the Elysee. It could not have been he, then, who had gone to the Post Office, the day after the 24th, to ask for a letter which he knew was no longer there.

“To me it appears clear that somebody, strongly resembling him, stole Mademoiselle Stangerson’s reticule and in that letter, had demanded of her something which she had not sent him. He must have been surprised at the failure of his demand, hence his application at the Post Office, to learn whether his letter had been delivered to the person to whom it had been addressed. Finding that it had been claimed, he had become furious. What had he demanded? Nobody but Mademoiselle Stangerson knows. Then, on the day following, it is reported that she had been attacked during the night, and, the next day, I discovered that the Professor had, at the same time, been robbed by means of the key referred to in the poste restante letter. It would seem, then, that the man who went to the Post Office to inquire for the letter must have been the murderer. All these arguments Larsan applies as against Monsieur Darzac. You may be sure that the examining magistrate, Larsan, and myself, have done our best to get from the Post Office precise details relative to the singular personage who applied there on the 24th of October. But nothing has been learned. We don’t know where he came from—or where he went. Beyond the description which makes him resemble Monsieur Darzac, we know nothing.

“I have announced in the leading journals that a handsome reward will be given to a driver of any public conveyance who drove a fare to No. 40, Post Office, about ten o’clock on the morning of the 24th of October. Information to be addressed to ‘M. R.,’ at the office of the ‘Epoque’; but no answer has resulted. The man may have walked; but, as he was most likely in a hurry, there was a chance that he might have gone in a cab. Who, I keep asking myself night and day, is the man who so strongly resembles Monsieur Robert Darzac, and who is also known to have bought the cane which has fallen into Larsan’s hands?

“The most serious fact is that Monsieur Darzac was, at the very same time that his double presented himself at the Post Office, scheduled for a lecture at the Sorbonne. He had not delivered that lecture, and one of his friends took his place. When I questioned him as to how he had employeed the time, he told me that he had gone for a stroll in the Bois de Boulogne. What do you think of a professor who, instead of giving his lecture, obtains a substitute to go for a stroll in the Bois de Boulogne? When Frederic Larsan asked him for information on this point, he quietly replied that it was no business of his how he spent his time in Paris. On which Fred swore aloud that he would find out, without anybody’s help.

“All this seems to fit in with Fred’s hypothesis, namely, that Monsieur Stangerson allowed the murderer to escape in order to avoid a scandal. The hypothesis is further substantiated by the fact that Darzac was in The Yellow Room and was permitted to get away. That hypothesis I believe to be a false one.—Larsan is being misled by it, though that would not displease me, did it not affect an innocent person. Now does that hypothesis really mislead Frederic Larsan? That is the question—that is the question.”

“Perhaps he is right,” I cried, interrupting Rouletabille. “Are you sure that Monsieur Darzac is innocent?—It seems to me that these are extraordinary coincidences—”

“Coincidences,” replied my friend, “are the worst enemies to truth.”

“What does the examining magistrate think now of the matter?”

“Monsieur de Marquet hesitates to accuse Monsieur Darzac, in the absence of absolute proofs. Not only would he have public opinion wholly against him, to say nothing of the Sorbonne, but Monsieur and Mademoiselle Stangerson. She adores Monsieur Robert Darzac. Indistinctly as she saw the murderer, it would be hard to make the public believe that she could not have recognised him, if Darzac had been the criminal. No doubt The Yellow Room was very dimly lit; but a night-light, however small, gives some light. Here, my boy, is how things stood when, three days, or rather three nights ago, an extraordinarily strange incident occurred.”

CHAPTER XIV. “I Expect the Assassin This Evening”

“I must take you,” said Rouletabille, “so as to enable you to understand, to the various scenes. I myself believe that I have discovered what everybody else is searching for, namely, how the murderer escaped from The Yellow Room, without any accomplice, and without Mademoiselle Stangerson having had anything to do with it. But so long as I am not sure of the real murderer, I cannot state the theory on which I am working. I can only say that I believe it to be correct and, in any case, a quite natural and simple one. As to what happened in this place three nights ago, I must say it kept me wondering for a whole day and a night. It passes all belief. The theory I have formed from the incident is so absurd that I would rather matters remained as yet unexplained.”

Saying which the young reporter invited me to go and make the tour of the chateau with him. The only sound to be heard was the crunching of the dead leaves beneath our feet. The silence was so intense that one might have thought the chateau had been abandoned. The old stones, the stagnant water of the ditch surrounding the donjon, the bleak ground strewn with the dead leaves, the dark, skeleton-like outlines of the trees, all contributed to give to the desolate place, now filled with its awful mystery, a most funereal aspect. As we passed round the donjon, we met the Green Man, the forest-keeper, who did not greet us, but walked by as if we had not existed. He was looking just as I had formerly seen him through the window of the Donjon Inn. He had still his fowling-piece slung at his back, his pipe was in his mouth, and his eye-glasses on his nose.

“An odd kind of fish!” Rouletabille said to me, in a low tone.

“Have you spoken to him?” I asked.

“Yes, but I could get nothing out of him. His only answers are grunts and shrugs of the shoulders. He generally lives on the first floor of the donjon, a big room that once served for an oratory. He lives like a bear, never goes out without his gun, and is only pleasant with the girls. The women, for twelve miles round, are all setting their caps for him. For the present, he is paying attention to Madame Mathieu, whose husband is keeping a lynx eye upon her in consequence.”

After passing the donjon, which is situated at the extreme end of the left wing, we went to the back of the chateau. Rouletabille, pointing to a window which I recognised as the only one belonging to Mademoiselle Stangerson’s apartment, said to me:

“If you had been here, two nights ago, you would have seen your humble servant at the top of a ladder, about to enter the chateau by that window.”

As I expressed some surprise at this piece of nocturnal gymnastics, he begged me to notice carefully the exterior disposition of the chateau. We then went back into the building.

“I must now show you the first floor of the chateau, where I am living,” said my friend.

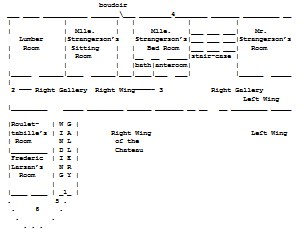

To enable the reader the better to understand the disposition of these parts of the dwelling, I annex a plan of the first floor of the right wing, drawn by Rouletabille the day after the extraordinary phenomenon occurred, the details of which I am about to relate.

Rouletabille motioned me to follow him up a magnificent flight of stairs ending in a landing on the first floor. From this landing one could pass to the right or left wing of the chateau by a gallery opening from it. This gallery, high and wide, extended along the whole length of the building and was lit from the front of the chateau facing the north. The rooms, the windows of which looked to the south, opened out of the gallery. Professor Stangerson inhabited the left wing of the building. Mademoiselle Stangerson had her apartment in the right wing.

We entered the gallery to the right. A narrow carpet, laid on the waxed oaken floor, which shone like glass, deadened the sound of our footsteps. Rouletabille asked me, in a low tone, to walk carefully, as we were passing the door of Mademoiselle Stangerson’s apartment. This consisted of a bed-room, an ante-room, a small bath-room, a boudoir, and a drawing-room. One could pass from one to another of these rooms without having to go by way of the gallery. The gallery continued straight to the western end of the building, where it was lit by a high window (window 2 on the plan). At about two-thirds of its length this gallery, at a right angle, joined another gallery following the course of the right wing.

The better to follow this narrative, we shall call the gallery leading from the stairs to the eastern window, the “right” gallery and the gallery quitting it at a right angle, the “off-turning” gallery (winding gallery in the plan). It was at the meeting point of the two galleries that Rouletabille had his chamber, adjoining that of Frederic Larsan, the door of each opening on to the “off-turning” gallery, while the doors of Mademoiselle Stangerson’s apartment opened into the “right” gallery. (See the plan.)

Rouletabille opened the door of his room and after we had passed in, carefully drew the bolt. I had not had time to glance round the place in which he had been installed, when he uttered a cry of surprise and pointed to a pair of eye-glasses on a side-table.

“What are these doing here?” he asked.

I should have been puzzled to answer him.

“I wonder,” he said, “I wonder if this is what I have been searching for. I wonder if these are the eye-glasses from the presbytery!”

He seized them eagerly, his fingers caressing the glass. Then looking at me, with an expression of terror on his face, he murmured, “Oh!—Oh!”

He repeated the exclamation again and again, as if his thoughts had suddenly turned his brain.

He rose and, putting his hand on my shoulder, laughed like one demented as he said:

“Those glasses will drive me silly! Mathematically speaking the thing is possible; but humanly speaking it is impossible—or afterwards—or afterwards—”

Two light knocks struck the door. Rouletabille opened it. A figure entered. I recognised the concierge, whom I had seen when she was being taken to the pavilion for examination. I was surprised, thinking she was still under lock and key. This woman said in a very low tone:

“In the grove of the parquet.”

Rouletabille replied: “Thanks.”—The woman then left. He again turned to me, his look haggard, after having carefully refastened the door, muttering some incomprehensible phrases.

“If the thing is mathematically possible, why should it not be humanly!—And if it is humanly possible, the matter is simply awful.” I interrupted him in his soliloquy:

“Have they set the concierges at liberty, then?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied, “I had them liberated, I needed people I could trust. The woman is thoroughly devoted to me, and her husband would lay down his life for me.”

“Oho!” I said, “when will he have occasion to do it?”

“This evening,—for this evening I expect the murderer.”

“You expect the murderer this evening? Then you know him?”

“I shall know him; but I should be mad to affirm, categorically, at this moment that I do know him. The mathematical idea I have of the murderer gives results so frightful, so monstrous, that I hope it is still possible that I am mistaken. I hope so, with all my heart!”

“Five minutes ago, you did not know the murderer; how can you say that you expect him this evening?”

“Because I know that he must come.”

Rouletabille very slowly filled his pipe and lit it. That meant an interesting story. At that moment we heard some one walking in the gallery and passing before our door. Rouletabille listened. The sound of the footstep died away in the distance.

“Is Frederic Larsan in his room?” I asked, pointing to the partition.

“No,” my friend answered. “He went to Paris this morning,—still on the scent of Darzac, who also left for Paris. That matter will turn out badly. I expect that Monsieur Darzac will be arrested in the course of the next week. The worst of it is that everything seems to be in league against him,—circumstances, things, people. Not an hour passes without bringing some new evidence against him. The examining magistrate is overwhelmed by it—and blind.”

“Frederic Larsan, however, is not a novice,” I said.

“I thought so,” said Rouletabille, with a slightly contemptuous turn of his lips, “I fancied he was a much abler man. I had, indeed, a great admiration for him, before I got to know his method of working. It’s deplorable. He owes his reputation solely to his ability; but he lacks reasoning power,—the mathematics of his ideas are very poor.”

I looked closely at Rouletabille and could not help smiling, on hearing this boy of eighteen talking of a man who had proved to the world that he was the finest police sleuth in Europe.

“You smile,” he said? “you are wrong! I swear I will outwit him—and in a striking way! But I must make haste about it, for he has an enormous start on me—given him by Monsieur Robert Darzac, who is this evening going to increase it still more. Think of it!—every time the murderer comes to the chateau, Monsieur Darzac, by a strange fatality, absents himself and refuses to give any account of how he employs his time.”

“Every time the assassin comes to the chateau!” I cried. “Has he returned then—?”

“Yes, during that famous night when the strange phenomenon occurred.”

I was now going to learn about the astonishing phenomenon to which Rouletabille had made allusion half an hour earlier without giving me any explanation of it. But I had learned never to press Rouletabille in his narratives. He spoke when the fancy took him and when he judged it to be right. He was less concerned about my curiosity than he was for making a complete summing up for himself of any important matter in which he was interested.

At last, in short rapid phrases, he acquainted me with things which plunged me into a state bordering on complete bewilderment. Indeed, the results of that still unknown science known as hypnotism, for example, were not more inexplicable than the disappearance of the “matter” of the murderer at the moment when four persons were within touch of him. I speak of hypnotism as I would of electricity, for of the nature of both we are ignorant and we know little of their laws. I cite these examples because, at the time, the case appeared to me to be only explicable by the inexplicable,—that is to say, by an event outside of known natural laws. And yet, if I had had Rouletabille’s brain, I should, like him, have had a presentiment of the natural explanation; for the most curious thing about all the mysteries of the Glandier case was the natural manner in which he explained them.

I have among the papers that were sent me by the young man, after the affair was over, a note-book of his, in which a complete account is given of the phenomenon of the disappearance of the “matter” of the assassin, and the thoughts to which it gave rise in the mind of my young friend. It is preferable, I think, to give the reader this account, rather than continue to reproduce my conversation with Rouletabille; for I should be afraid, in a history of this nature, to add a word that was not in accordance with the strictest truth.

CHAPTER XV. The Trap

(EXTRACT FROM THE NOTE-BOOK OF JOSEPH ROULETABILLE)“Last night—the night between the 29th and 30th of October—” wrote Joseph Rouletabille, “I woke up towards one o’clock in the morning. Was it sleeplessness, or noise without?—The cry of the Bete du Bon Dieu rang out with sinister loudness from the end of the park. I rose and opened the window. Cold wind and rain; opaque darkness; silence. I reclosed my window. Again the sound of the cat’s weird cry in the distance. I partly dressed in haste. The weather was too bad for even a cat to be turned out in it. What did it mean, then—that imitating of the mewing of Mother Angenoux’ cat so near the chateau? I seized a good-sized stick, the only weapon I had, and, without making any noise, opened the door.