полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Volume 2, No. 12, May, 1851.

Phillips, Sampson, and Co. have published a valuable collection of financial essays, entitled The Banker's Commonplace Book, containing Mr. A. B. Johnson's pithy treatise on the Principles of Banking and the Duties of a Banker, Gilbart's Ten Minutes' Advice on Keeping a Bank, with several articles on Bills of Exchange, and a summary of the Banking Laws of Massachusetts. It will prove a useful manual on the subject to which it is devoted.

TWO LEAVES FROM PUNCH

DIPLOMACY AND GASTRONOMYIt is a very generally received opinion that gammon is the basis of diplomacy; but the fact is, that it is impossible to conduct international negotiations on the foundation of that humble and economical fare, even when rendered more palatable by the addition of spinach. Mr. Rives, it is said, has written a letter to Mr. Webster, complaining that the American Embassadorship can not be done at Paris under £9000 a year, and adds that

"According to Mr. Pakenham, good dinners are half the battle of diplomacy, and the most favorable treaties are gained by liberal feeding."

This aphorism suggests important reflections.

A main point to be attended to in the formation of a diplomatic corps is the commissariat; and the force must be well armed with knives and forks, in addition to being supplied with plate armor.

The trenches in diplomatic warfare must be manned by regular trenchermen.

Rivals in diplomacy must be cut out by actual carving; and in order to dish them, recourse must be had to real dishes.

If one diplomatist wishes to turn the tables on another, it is requisite that he and his suite should keep the better tables.

The politeness of diplomatic intercourse should be qualified, in some measure, with sauce, and its gravity tempered with gravy.

Treating, in diplomacy, is best managed by giving "a spread."

Bold diplomatists are those "who greatly daring, dine."

The most liberal foreign policy is that of giving grand banquets.

A plenipotentiary should have unlimited powers of cramming.

An embassador has been defined to be, "a man sent abroad to lie for the sake of the commonwealth;" but the definition must be enlarged to express the fact, that he is also a person deputed to a foreign country to eat and drink for the interest of his native land.

The most important diplomatic functions are those of digestion.

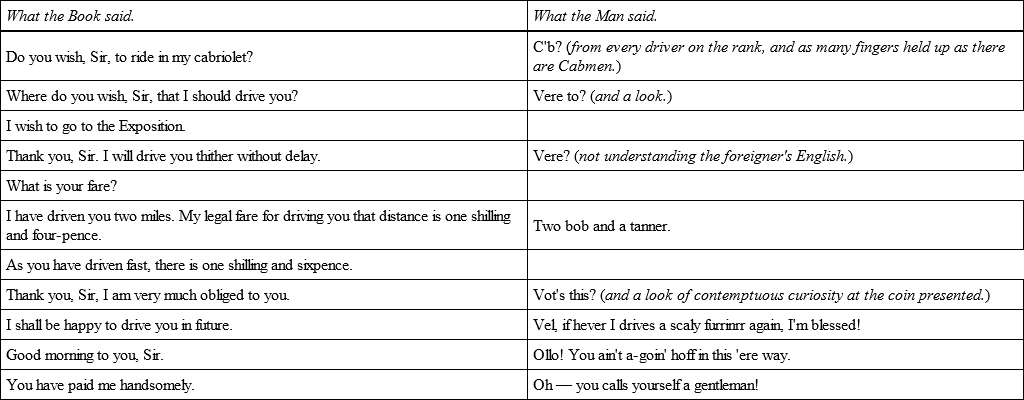

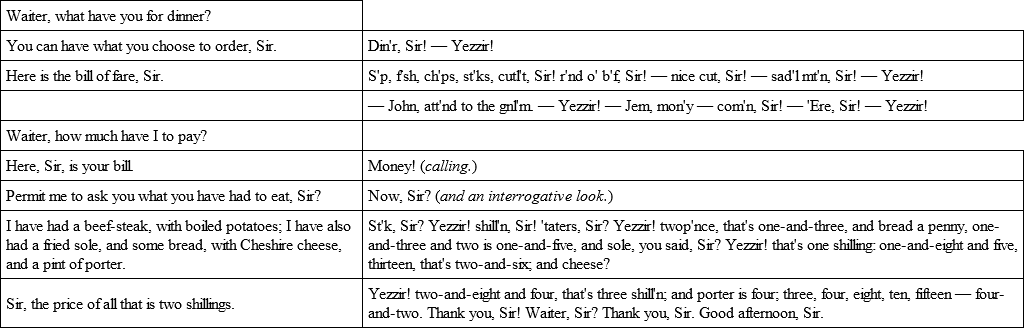

CONVERSATION-BOOKS FOR 1851It is said that Publishers are getting up a series of Conversation-Books for the use of foreigners, visiting the Great Exhibition. But the spoken and written language of London are so different that it is feared these books will be of little use. Mr. PUNCH furnishes the following corrections of the two most important chapters, by the diligent study of which it is hoped that visitors may be enabled to ride and dine.

TO CONVERSE WITH A CABMAN

Conductor.– Would any gentleman mind going outside, to oblige a lady?

Unfortunate Gentleman (tightly wedged in at the back). – I should be very happy, but I only came, yesterday, out of the Fever Hospital.

[Omnibus clears in a minute!A FILE TO SMOOTH ASPERITIESThe Sheffield Times describes an extraordinary file, which is to be sent from Sheffield to the Great Exhibition. This remarkable file is adorned with designs as numerous as those on the original shield of Achilles, all cut and beaten out with hammer and chisel. How much more sensible and friendly to show distinguished foreigners files of this sort, than to exhibit to them files of soldiers!

THE LOWEST DEPTH OF MEANNESSA FARCE, FOUNDED ON FACTMr. and Mrs. Skinflint are discovered in a Parlor in a Fashionable Square. The Wife is busy sewing. The Husband is occupied running his eye, well drilled in all matters of domestic economy, over the housekeeping account of the previous week.

Mr. Skinflint.– You've been very extravagant in my absence, my dear.

Mrs. Skinflint.– It's the same story every week, John.

Mr. Skinflint.– But, nonsense, Madam, I tell you, you have. For instance, you had a Crab for supper last night.

Mrs. Skinflint (startled).– How do you know that? It's not down in the book.

Mr. Skinflint (triumphantly).– No – but I found the shell in the dust-bin!!!!

FASHIONS FOR MAY

This is the season when Fashion is more perplexed than at any other, in her endeavors to give humanity a seasonable garb. Boreas and Zephyrus often bear rule on the same day, one reigning with mildness in the morning, the other despotically at evening. Those votaries of Fashion are the wiser, who pay court to the former; for, generally, it is almost June, in our Northern States, before we may be certain that the chilling breath of early Spring will be no more felt.

This being the season for rides and promenades, our illustrations for this month are devoted chiefly to the representation of appropriate costume for those healthful exercises in the open air. The large figure in our first plate, represents an elegant style of promenade dress. Pardessus are much worn at this season, made in a lighter manner than those used earlier. Velvet pardessus with silk or satin linings, but not padded, are used. Our illustration represents one of black velvet, trimmed with several narrow rows of satin of the same color. The dress is amber-colored figured silk, with a very full plain skirt. Capotes or bonnets of satin are also worn. An elegant style is made of violet velvet and satin, ornamented with heart's-ease almost hidden within coques of satin and velvet, which are arranged in a tasteful manner upon the exterior of the capote, the interior being decorated with heart's-ease to match, which may or may not be intermixed with lace or tulle, according to the taste of the wearer.

Costumes for young misses are also represented in our first illustration. The larger one has a dress of a pale chocolate cachmere, trimmed with narrow silk fringe; the double robings on each side of the front as well as the cape, on the half-high corsage, ornamented with a double row of narrow silk fringe. This trimming is also repeated round the lower part of the loose sleeve. Chemisette of plaited cambric, headed with a broad frill of embroidery; full under-sleeves of cambric, with a row of embroidery round the wrist. Open bonnet of pink satin, a row of white lace encircling the interior next the face. Boots of pale violet cachmere and morocco. Trowsers of worked cambric. The smaller figure has a frock of plaided cachmere. Paletot of purple velvet, or dark cachmere; a round hat of white satin, the low crown adorned with a long white ostrich feather. Trowsers and under-sleeves of white embroidered cambric. Button gaiter boots of chocolate cachmere.

Represents a most elegant costume for an evening party, or a ball. It is composed of a beautifully embroidered white satin dress, the skirt looped up on the right side, and decorated with a bunch of the pink honey-plant, heading three pink and white marabout tips, from which depend three ends of deep silk fringe, pink and white. Low pointed corsage, the top of which is encircled with a small embroidered pointed cape, edged as well as the short sleeves with a deep pink and white fringe, and confined upon the centre with a cluster of feathers and flowers, decorated in the centre with a butterfly composed of precious stones. The hair is simply arranged with a narrow wreath of pink and white velvet leaves, finished on the right side with two small marabout feathers, and two ends of fringe drooping low.

Is a morning promenade costume. A high dress of black satin, the body fitting perfectly tight; a small jacket cut on the bias, with two rows of black velvet laid on a little distance from the edge. The sleeves are rather large, and have abroad cuff turned back, which is trimmed to correspond with the jacket. The skirt is long and full; the dress ornamented up the front in its whole length by rich fancy silk trimmings, graduating in size from the bottom of the skirt to the waist, and again increasing to the throat. Bonnet of plum-colored satin; a bunch of heart's-ease, intermixed with ribbon, placed low on the left side; the same flowers, but somewhat smaller, ornament the interior.

Represent different styles of head-dresses for balls or evening parties. Is a combination of flowers and splendid ribbons, with a fall on each side, of the richest lace. Is very brilliant. It is a wreath of Ceres form, composed of small flowers in rubies, emeralds, and diamonds, perfectly resembling natural flowers, with ears of wheat freely intermingled. At this season the head-dresses are chiefly of the floral description. Feathers and flowers intermixed, form a very beautiful coiffure.

1

Fauna Boreali Americana, p. 62.

2

Holland's Plinie's Naturall Historie, ed. 1635

3

Edit, Edin. 1541, quoted from Magazine of Natural History.

4

Private Journal of Captain G. F. Lyon, 1824.

5

Private Journal of Captain G. F. Lyon, 1824.

6

From a work entitled "Scenes of Italian Life," by L. Mariotti, just published in London.

7

Continued from the April Number.

8

This aphorism has been probably assigned to Lord Bacon upon the mere authority of the index to his works. It is the aphorism of the index-maker, certainly not of the great master of inductive philosophy. Bacon has, it is true, repeatedly dwelt on the power of knowledge, but with so many explanations and distinctions, that nothing could be more unjust to his general meaning than to attempt to cramp into a sentence what it costs him a volume to define. Thus, if in one page he appears to confound knowledge with power, in another he sets them in the strongest antithesis to each other; as follows, "Adeo, signanter Deus opera potentiæ et sapientiæ diseriminavit." But it would be as unfair to Bacon to convert into an aphorism the sentence that discriminates between knowledge and power as it is to convert into an aphorism any sentence that confounds them.

9

"But the greatest error of all the rest is the mistaking or misplacing of the last or farthest end of knowledge: – for men have entered into a desire of learning and knowledge, sometimes upon a natural curiosity and inquisitive appetite; sometimes to entertain their minds with variety and delight; sometimes for ornament and reputation; and sometimes to enable them to victory of wit and contradiction; and most times for lucre and profession;" – [that is, for most of those objects which are meant by the ordinary citers of the saying, 'Knowledge is power;'] "and seldom, sincerely, to give a true account of these gifts of reason to the benefit and use of men; as if there were sought in knowledge a couch whereupon to rest a searching and restless spirit; or a terrace for a wandering and variable mind to walk up and down, with a fair prospect; or a tower of state for a proud mind to raise itself upon; or a fort or commanding ground for strife and contention; or a shop for profit or sale – and not a rich storehouse for the glory of the Creator, and the relief of men's estate." – Advancement of Learning, Book I.