полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Volume 1, No. 4, September, 1850

A multitude of theories have been devised to account for the origin of these remarkable bodies. The idea is completely inadmissible that they are concretions formed within the limits of the atmosphere. The ingredients that enter into their composition have never been discovered in it, and the air has been analyzed at the sea level and on the tops of high mountains. Even supposing that to have been the case, the enormous volume of atmospheric air so charged required to furnish the particles of a mass of several tons, not to say many masses, is, alone, sufficient to refute the notion. They can not, either, be projectiles from terrestrial volcanoes, because coincident volcanic activity has not been observed, and aërolites descend thousands of miles apart from the nearest volcano, and their substances are discordant with any known volcanic product. Laplace suggested their projection from lunar volcanoes. It has been calculated that a projectile leaving the lunar surface, where there is no atmospheric resistance, with a velocity of 7771 feet in the first second, would be carried beyond the point where the forces of the earth and the moon are equal, would be detached, therefore, from the satellite, and come so far within the sphere of the earth’s attraction as necessarily to fall to it. But the enormous number of ignited bodies that have been visible, the shooting stars of all ages, and the periodical meteoric showers that have astonished the moderns, render this hypothesis untenable, for the moon, ere this, would have undergone such a waste as must have sensibly diminished her orb, and almost blotted her from the heavens. Olbers, was the first to prove the possibility of a projectile reaching us from the moon, but at the same he deemed the event highly improbable, regarding the satellite as a very peaceable neighbor, not capable now of strong explosions from the want of water and an atmosphere. The theory of Chladni will account generally for all the phenomena, be attended with the fewest difficulties, and, with some modifications to meet circumstances not known in his day, it is now widely embraced. He conceived the system to include an immense number of small bodies, either the scattered fragments of a larger mass, or original accumulations of matter, which, circulating round the sun, encounter the earth in its orbit, and are drawn toward it by attraction, become ignited upon entering the atmosphere, in consequence of their velocity, and constitute the shooting stars, aërolites, and meteoric appearances that are observed. Sir Humphry Davy, in a paper which contains his researches on flame, strongly expresses an opinion that the meteorites are solid bodies moving in space, and that the heat produced by the compression of the most rarefied air from the velocity of their motion must be sufficient to ignite their mass so that they are fused on entering the atmosphere. It is estimated that a body moving through our atmosphere with the velocity of one mile in a second, would extricate heat equal to 30,000° of Fahrenheit – a heat more intense than that of the fiercest artificial furnace that ever glowed. The chief modification given to the Chladnian theory has arisen from the observed periodical occurrence of meteoric showers – a brilliant and astonishing exhibition – to some notices of which we proceed.

The writers of the middle ages report the occurrence of the stars falling from heaven in resplendent showers among the physical appearances of their time. The experience of modern days establishes the substantial truth of such relations, however once rejected as the inventions of men delighting in the marvelous. Conde, in his history of the dominion of the Arabs, states, referring to the month of October in the year 902 of our era, that on the night of the death of King Ibrahim ben Ahmed, an infinite number of falling stars were seen to spread themselves like rain over the heavens from right to left, and this year was afterward called the year of stars. In some Eastern annals of Cairo, it is related that “In this year (1029 of our era) in the month Redjeb (August) many stars passed, with a great noise, and brilliant light;” and in another place the same document states: “In the year 599, on Saturday night, in the last Moharrem (1202 of our era, and on the 19th of October), the stars appeared like waves upon the sky, toward the east and west; they flew about like grasshoppers, and were dispersed from left to right; this lasted till day-break; the people were alarmed.” The researches of the Orientalist, M. Von Hammer, have brought these singular accounts to light. Theophanes, one of the Byzantine historians, records, that in November of the year 472 the sky appeared to be on fire over the city of Constantinople with the coruscations of flying meteors. The chronicles of the West agree with those of the East in reporting such phenomena. A remarkable display was observed on the 4th of April, 1095, both in France and England. The stars seemed, says one, “falling like a shower of rain from heaven upon the earth;” and in another case, a bystander, having noted the spot where an aërolite fell, “cast water upon it, which was raised in steam, with a great noise of boiling.” The chronicle of Rheims describes the appearance, as if all the stars in heaven were driven like dust before the wind. “By the reporte of the common people, in this kynge’s time (William Rufus),” says Rastel, “divers great wonders were sene – and therefore the king was told by divers of his familiars, that God was not content with his lyvyng, but he was so wilful and proude of minde, that he regarded little their saying.” There can be no hesitation now in giving credence to such narrations as these, since similar facts have passed under the notice of the present generation.

The first grand phenomena of a meteoric shower which attracted attention in modern times was witnessed by the Moravian Missionaries at their settlements in Greenland. For several hours the hemisphere presented a magnificent and astonishing spectacle, that of fiery particles, thick as hail, crowding the concave of the sky, as though some magazine of combustion in celestial space was discharging its contents toward the earth. This was observed over a wide extent of territory. Humboldt, then traveling in South America, accompanied by M. Bonpland, thus speaks of it: “Toward the morning of the 13th November, 1799, we witnessed a most extraordinary scene of shooting meteors. Thousands of bodies and falling stars succeeded each other during four hours. Their direction was very regular from north to south. From the beginning of the phenomenon there was not a space in the firmament equal in extent to three diameters of the moon which was not filled every instant with bodies of falling stars. All the meteors left luminous traces or phosphorescent bands behind them, which lasted seven or eight seconds.” An agent of the United States, Mr. Ellicott, at that time at sea between Cape Florida and the West India Islands, was another spectator, and thus describes the scene: “I was called up about three o’clock in the morning, to see the shooting stars, as they are called. The phenomenon was grand and awful The whole heavens appeared as if illuminated with sky-rockets, which disappeared only by the light of the sun after daybreak. The meteors, which at any one instant of time appeared as numerous as the stars, flew in all possible directions, except from the earth, toward which they all inclined more or less; and some of them descended perpendicularly over the vessel we were in, so that I was in constant expectation of their falling on us.” The same individual states that his thermometer, which had been at 80° Fahr. for four days preceding, fell to 56°, and, at the same time, the wind changed from the south to the northwest, from whence it blew with great violence for three days without intermission. The Capuchin missionary at San Fernando, a village amid the savannahs of the province of Varinas, and the Franciscan monks stationed near the entrance of the Oronoco, also observed this shower of asteroids, which appears to have been visible, more or less, over an area of several thousand miles, from Greenland to the equator, and from the lonely deserts of South America to Weimar in Germany. About thirty years previous, at the city of Quito, a similar event occurred. So great a number of falling stars were seen in a part of the sky above the volcano of Cayambaro, that the mountain itself was thought at first to be on fire. The sight lasted more than an hour. The people assembled in the plain of Exida, where a magnificent view presented itself of the highest summits of the Cordilleras. A procession was already on the point of setting out from the convent of Saint Francis, when it was perceived that the blaze on the horizon was caused by fiery meteors, which ran along the sky in all directions, at the altitude of twelve or thirteen degrees. In Canada, in the years 1814 and 1819, the stellar showers were noticed, and in the autumn of 1818 on the North Sea, when, in the language of one of the observers, the surrounding atmosphere seemed enveloped in one expansive ocean of fire, exhibiting the appearance of another Moscow in flames. In the former cases, a residiuum of dust was deposited upon the surface of the waters, on the roofs of buildings, and on other objects. The deposition of particles of matter of a ruddy color has frequently followed the descent of aërolites – the origin of the popular stories of the sky having rained blood. The next exhibition upon a great scale of the falling stars occurred on the 13th of November, 1831, and was seen off the coasts of Spain and in the Ohio country. This was followed by another in the ensuing year at exactly the same time. Captain Hammond, then in the Red Sea, off Mocha, in the ship Restitution, gives the following account of it; “From one o’clock A.M. till after daylight, there was a very unusual phenomenon in the heavens. It appeared like meteors bursting in every direction. The sky at the time was clear, and the stars and moon bright, with streaks of light and thin white clouds interspersed in the sky. On landing in the morning, I inquired of the Arabs if they had noticed the above. They said they had been observing it most of the night. I asked them if ever the like had appeared before? The oldest of them replied it had not.” The shower was witnessed from the Red Sea westward to the Atlantic, and from Switzerland to the Mauritius.

We now come to by far the most splendid display on record; which, as it was the third in successive years, and on the same day of the month as the two preceding, seemed to invest the meteoric showers with a periodical character; and hence originated the title of the November meteors. The chief scene of the exhibition was included within the limits of the longitude of 61° in the Atlantic Ocean, and that of 100° in Central Mexico, and from the North American lakes to the West Indies. Over this wide area, an appearance presented itself, far surpassing in grandeur the most imposing artificial fire-works. An incessant play of dazzlingly brilliant luminosities was kept up in the heavens for several hours. Some of these were of considerable magnitude and peculiar form. One of large size remained for some time almost stationary in the zenith, over the Falls of Niagara, emitting streams of light. The wild dash of the waters, as contrasted with the fiery uproar above them, formed a scene of unequaled sublimity. In many districts, the mass of the population were terror-struck, and the more enlightened were awed at contemplating so vivid a picture of the Apocalyptic image – that of the stars of heaven falling to the earth, even as a fig-tree casting her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind. A planter of South Carolina, thus describes the effect of the scene upon the ignorant blacks: “I was suddenly awakened by the most distressing cries that ever fell on my ears. Shrieks of horror and cries for mercy I could hear from most of the negroes of three plantations, amounting in all to about six or eight hundred. While earnestly listening for the cause, I heard a faint voice near the door calling my name. I arose, and taking my sword, stood at the door. At this moment, I heard the same voice still beseeching me to rise, and saying, ‘O my God, the world is on fire!’ I then opened the door, and it is difficult to say which excited me most – the awfulness of the scene, or the distressed cries of the negroes. Upward of one hundred lay prostrate on the ground – some speechless, and some with the bitterest cries, but with their hands raised, imploring God to save the world and them. The scene was truly awful; for never did rain fall much thicker than the meteors fell toward the earth; east, west, north, and south, it was the same.”

This extraordinary spectacle commenced a little before midnight, and reached its height between four and six o’clock in the morning. The night was remarkably fine. Not a cloud obscured the firmament. Upon attentive observation, the materials of the shower were found to exhibit three distinct varieties: – 1. Phosphoric lines formed one class apparently described by a point. These were the most abundant. They passed along the sky with immense velocity, as numerous as the flakes of a sharp snow-storm. 2. Large fire-balls formed another constituency of the scene. These darted forth at intervals along the arch of the sky, describing an arc of 30° or 40° in a few seconds. Luminous trains marked their path, which remained in view for a number of minutes, and in some cases for half an hour or more. The trains were commonly white, but the various prismatic colors occasionally appeared, vividly and beautifully displayed. Some of these fire-balls, or shooting-stars, were of enormous size. Dr. Smith of North Carolina observed one which appeared larger than the full moon at the horizon. “I was startled,” he remarks, “by the splendid light in which the surrounding scene was exhibited, rendering even small objects quite visible.” The same, or a similar luminous body, seen at New Haven, passed off in a northwest direction, and exploded near the star Capella. 3. Another class consisted of luminosities of irregular form, which remained nearly stationary for a considerable time, like the one that gleamed aloft over the Niagara Falls. The remarkable circumstance is testified by every witness, that all the luminous bodies, without a single exception, moved in lines, which converged in one and the same point of the heavens; a little to the southeast of the zenith. They none of them started from this point, but their direction, to whatever part of the horizon it might be, when traced backward, led to a common focus. Conceive the centre of the diagram to be nearly overhead, and a proximate idea may be formed of the character of the scene, and the uniform radiation of the meteors from the same source. The position of this radiant point among the stars was near γ Leonis. It remained stationary with respect to the stars during the whole of the exhibition. Instead of accompanying the earth in its diurnal motion eastward, it attended the stars in their apparent movement westward. The source of the meteoric shower was thus independent of the earth’s rotation, and this shows its position to have been in the regions of space exterior to our atmosphere. According to the American Professor, Dr. Olmsted, it could not have been less than 2238 miles above the earth’s surface.

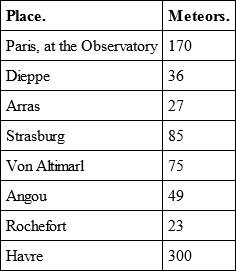

The attention of astronomers in Europe, and all over the world, was, as may be imagined, strongly roused by intelligence of this celestial display on the western continent; and as the occurrence of a meteoric shower had now been observed for three years successively, at a coincident era, it was inferred that a return of this fiery hail-storm might be expected in succeeding Novembers. Arrangements were therefore made to watch the heavens on the nights of the 12th and 13th in the following years at the principal observatories; and though no such imposing spectacle as that of 1833 has been witnessed, yet extraordinary flights of shooting stars have been observed in various places at the periodic time, tending also from a fixed point in the constellation Leo. They were seen in Europe and America on November 13th, 1834. The following results of simultaneous observation were obtained by Arago from different parts of France on the nights of November 12th and 13th, 1830:

On November 12th, 1837, at eight o’clock in the evening, the attention of observers in various parts of Great Britain was directed to a bright, luminous body, apparently proceeding from the north, which, after making a rapid descent, in the manner of a rocket, suddenly burst, and scattering its particles into various beautiful forms, vanished in the atmosphere. This was succeeded by others all similar to the first, both in shape and the manner of its ultimate disappearance. The whole display terminated at ten o’clock, when dark clouds which continued up to a late hour, overspread the earth, preventing any further observation. In the November of 1838, at the same date, the falling stars were abundant at Vienna: and one of remarkable brilliancy and size, as large as the full moon in the zenith, was seen on the 13th by M. Verusmor, off Cherburg, passing in the direction of Cape La Hogue, a long, luminous train marking its course through the sky. The same year, the non-commissioned officers in the island of Ceylon were instructed to look out for the falling stars. Only a few appeared at the usual time; but on the 5th of December, from nine o’clock till midnight, the shower was incessant, and the number defied all attempts at counting them.

Professor Olmsted, an eminent man of science, himself an eye-witness of the great meteoric shower on the American continent, after carefully collecting and comparing facts, proposed the following theory: The meteors of November 13th, 1833, emanated from a nebulous body which was then pursuing its way along with the earth around the sun; that this body continues to revolve around the sun in an elliptical orbit, but little inclined to the plane of the ecliptic, and having its aphelion near the orbit of the earth; and finally, that the body has a period of nearly six months, and that its perihelion is a little within the orbit of Mercury. The diagram represents the ellipse supposed to be described, E being the orbit of the earth, M that of Mercury, and N that of the assumed nebula, its aphelion distance being about 95 millions of miles, and the perihelion 24 millions. Thus, when in aphelion, the body is close to the orbit of the earth, and this occurring periodically, when the earth is at the same time in that part of its orbit, nebulous particles are attracted toward it by its gravity, and then, entering the atmosphere, are consumed in it by their concurrent velocities, causing the appearance of a meteoric shower. The parent body is inferred to be nebular, because, though the meteors fall toward the earth with prodigious velocity, few, if any, appear to have reached the surface. They were stopped by the resistance of the air and dissipated in it, whereas, if they had possessed any considerable quantity of matter, the momentum would have been sufficient to have brought them down in some instances to the earth. Arago has suggested a similar theory, that of a stream or group of innumerable bodies, comparatively small, but of various dimensions, sweeping round the solar focus in an orbit which periodically cuts that of the earth. These two theories are in substance the Chladnian hypothesis, first started to explain the observed actual descent of aërolites. Though great obscurity rests upon the subject, the fact may be deemed certain that independently of the great planets and satellites of the system, there are vast numbers of bodies circling round the sun, both singly and in groups, and probably an extensive nebula, contact with which causes the phenomena of shooting stars, aërolites, and meteoric showers. But admitting the existence of such bodies to be placed beyond all doubt, the question of their origin, whether original accumulations of matter, old as the planetary orbs, or the dispersed trains of comets, or the remains of a ruined world, is a point beyond the power of the human understanding to reach.

A FIVE DAYS’ TOUR IN THE ODENWALD

A SKETCH OF GERMAN LIFEBY WILLIAM HOWITTThe Odenwald, or Forest of Odin, is one of the most primitive districts of Germany. It consists of a hilly, rather than a mountainous district, of some forty miles in one direction, and thirty in another. The beautiful Neckar bounds it on the south; on the west it is terminated by the sudden descent of its hills into the great Rhine plain. This boundary is well known by the name of the Bergstrasse, or mountain road; which road, however, was at the foot of the mountains, and not over them, as the name would seem to imply. To English travelers, the beauty of this Bergstrasse is familiar. The hills, continually broken into by openings into romantic valleys, slope rapidly down to the plain, covered with picturesque vineyards; and at their feet lie antique villages, and the richly-cultivated plains of the Rhine, here thirty or forty miles wide. On almost every steep and projecting hill, or precipitous cliff, stands a ruined castle, each, as throughout Germany, with its wild history, its wilder traditions, and local associations of a hundred kinds. The railroad from Frankfort to Heidelberg now runs along the Bergstrasse, and will ever present to the eyes of travelers the charming aspect of these old legendary hills; till the enchanting valley of the Neckar, with Heidelberg reposing amid its lovely scenery at its mouth, terminates the Bergstrasse, and the hills which stretch onward, on the way toward Carlsruhe, assume another name.

Every one ascending the Rhine from Mayence to Mannheim has been struck with the beauty of these Odenwald hills, and has stood watching that tall white tower on the summit of one of them, which, with windings of the river, seem now brought near, and then again thrown very far off; seemed to watch and haunt you, and, for many hours, to take short cuts to meet you, till, at length, like a giant disappointed of his prey, it glided away into the gray distance, and was lost in the clouds. This is the tower of Melibocus, above the village of Auerbach, to which we shall presently ascend, in order to take our first survey of this old and secluded haunt of Odin.

This quiet region of hidden valleys and deep forests extends from the borders of the Black Forest, which commences on the other side of the Neckar, to the Spessart, another old German forest; and in the other direction, from Heidelberg and Darmstadt, toward Heilbronn. It is full of ancient castles, and a world of legends. In it stands, besides the Melibocus, another tower, on a still loftier point, called the Katzenbuckel, which overlooks a vast extent of these forest hills. Near this lies Eberbach, a castle of the descendants of Charlemagne, which we shall visit; the scenes of the legend of the Wild Huntsman; the castles of Götz von Berlichingen, and many another spot familiar by its fame to our minds from childhood. But besides this, the inhabitants are a people living in a world of their own; retaining all the simplicity of their abodes and habits; and it is only in such a region that you now recognize the pictures of German life such as you find them in the Haus Märchen of the brothers Grimm.

In order to make ourselves somewhat acquainted with this interesting district, Mrs. Howitt and myself, with knapsack on back, set out at the end of August, 1841, to make a few days’ ramble on foot through it. The weather, however, proved so intensely hot, and the electrical sultriness of the woods so oppressive, that we only footed it one day, when we were compelled to make use of a carriage, much to our regret.

On the last day in August we drove with a party of friends, and our children, to Weinheim; rambled through its vineyards, ascended to its ancient castle, and then went on to Birkenau Thal, a charming valley, celebrated, as its name denotes, for its lovely hanging birches, under which, with much happy mirth, we dined.

Scrambling among the hills, and winding up the dry footpaths, among the vineyards of this neighborhood, we were yet more delighted with the general beauty of the scenery, and with the wild-flowers which every where adorned the hanging cliffs and warm waysides. The marjorum stood in ruddy and fragrant masses; harebells and campanulas of several kinds, that are cultivated in our gardens, with bells large and clear; crimson pinks; the Michaelmas daisy; a plant with a thin, radiated yellow flower, of the character of an aster; a centaurea of a light purple, handsomer than any English one; a thistle in the dryest places, resembling an eryngo, with a thick, bushy top; mulleins, yellow and white; the wild mignonnette, and the white convolvulus; and clematis festooning the bushes, recalled the flowery fields and lanes of England, and yet told us that we were not there. The meadows had also their moist emerald sward scattered with the grass of Parnassus, and an autumnal crocus of a particularly delicate lilac.