полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. 1. No 1, June 1850

Sitting one evening with an intelligent German Jew, who used often to pay me a visit at my lodgings, the conversation turned on Jewish religious rites and ceremonies. Alluding to the day of atonement, he assured me that on that day the Jews believe that ministers are appointed in heaven for the ensuing year: a minister over angels; one over the stars; one over earth; the winds, trees, plants, birds, beasts, fishes, men, and so forth.

That, on that day also, the good and evil deeds of every son of Abraham are actually summed up, and the balance struck for or against each, individually. Where the evil deeds preponderate, such individuals are brought in as in debt to the law; and ten days after the day of atonement, summonses are issued to call the defaulters before God. When these are served, the party summoned to appear is visited either with sudden death or a rapid and violent disease which must terminate speedily in death. "But can not the divine wrath be appeased?" said I. "Not appeased," said my informant; "the decree must be evaded." "How so?" "Thus," he replied. "When a Jew is struck with sudden sickness about this time, if he apprehends that his call is come, he sends immediately for twelve elders of his people; they demand his name; he tells them, for example, my name is Isaac; they answer, thy name shall no more be Isaac, but Jacob shall thy name be called. Then kneeling round the sick roan, they pray for him in these words: O God, thy servant, Isaac, has not good deeds to exceed the evil, and a summons against him has gone forth; but this pious man before thee, is named Jacob, and not Isaac. There is a flaw in the indictment; the name in the angel's summons is not correct, therefore, thy servant Jacob can not be called on to appear." "After all," said I, "suppose this Jacob dies." "Then," replied my companion, "the Almighty is unjust; the summons was irregular, and its execution not according to law."

Does not this appear incredible? Another anecdote, and I have done.

On the same occasion we were speaking about vows, and the obligation of fulfilling them. "As to paying your vow," said my Jewish friend, "we consider it performed, if the vow be observed to the letter." He then gave me the following rather ludicrous illustration as a case in point: There was in his native village a wealthy Jew, who was seized with a dangerous illness. Seeing death approach, despite of his physician's skill, he bethought him of vowing a vow; so he solemnly promised, that if God would restore him to health, he, on his part, on his recovery, would sell a certain fat beast in his stall, and devote the proceeds to the Lord.

The man recovered, and in due time appeared before the door of the synagogue, driving before him a goodly ox, and carrying under one arm a large, black Spanish cock. The people were coming out of the synagogue, and several Jewish butchers, after artistically examining the fine, fat beast, asked our convalescent what might be the price of the ox. "This ox," replied the owner, "I value at two shillings (I substitute English money); but the cock," he added, ostentatiously exhibiting chanticleer, "I estimate at twenty pounds." The butchers laughed at him; they thought he was in joke. However, as he gravely persisted that he was in earnest, one of them, taking him at his word, put down two shillings for the ox. "Softly, my good friend," rejoined the seller, "I have made a vow not to sell the ox without the cock; you must buy both, or be content with neither." Great was the surprise of the bystanders, who could not conceive what perversity possessed their wealthy neighbor. But the cock being value for two shillings, and the ox for twenty pounds, the bargain was concluded, and the money paid.

Our worthy Jew now walks up to the Rabbi, cash in hand. "This," said he, handing the two shillings, "I devote to the service of the synagogue, being the price of the ox, which I had vowed; and this, placing the twenty pounds in his own bosom, is lawfully mine own, for is it not the price of the cock?" "And what did your neighbors say of the transaction? Did they not think this rich man an arrant rogue?" "Rogue!" said my friend, repeating my last words with some amazement, "they considered him a pious and a clever man." Sharp enough, thought I; but delicate about exposing my ignorance, I judiciously held my peace.

[From Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.]THE MODERN ARGONAUTS

iYou have heard the ancient story,How the gallant sons of Greece,Long ago, with Jason venturedFor the fated Golden Fleece;How they traversed distant regions,How they trod on hostile shores;How they vexed the hoary OceanWith the smiting of their oars; —Listen, then, and you shall hear another wondrous tale,Of a second Argo steering before a prosperous gale!iiFrom the southward came a rumor,Over sea and over land;From the blue Ionian islands,And the old Hellenic strand,That the sons of Agamemnon,To their faith no longer true,Had confiscated the carpetsOf a black and bearded Jew!Helen's rape, compared to this, was but an idle toy,Deeper guilt was that of Athens than the crime of haughty Troy.iiiAnd the rumor, winged by Ate,To the lofty chamber ran,Where great Palmerston was sittingIn the midst of his Divan:Like Saturnius triumphant,In his high Olympian hall,Unregarded by the mighty,But detested by the small;Overturning constitutions – setting nations by the ears,With divers sapient plenipos, like Minto and his peers.ivWith his fist the proud dictatorSmote the table that it rang —From the crystal vase before himThe blood-red wine upsprang!"Is my sword a wreath of rushes,Or an idle plume my pen,That they dare to lay a fingerOn the meanest of my men?No amount of circumcision can annul the Briton's right —Are they mad, these lords of Athens, for I know they can not fight?v"Had the wrong been done by others,By the cold and haughty Czar,I had trembled ere I openedAll the thunders of my war.But I care not for the yelpingOf these fangless curs of Greece —Soon and sorely will I tax themFor the merchant's plundered Fleece.From the earth his furniture for wrath and vengeance cries —Ho, Eddisbury! take thy pen, and straightway write to Wyse!"viJoyfully the bells are ringingIn the old Athenian town,Gayly to Piræus harborStream the merry people down;For they see the fleet of BritainProudly steering to their shore,Underneath the Christian bannerThat they knew so well of yore,When the guns at Navarino thundered o'er the sea,And the Angel of the North proclaimed that Greece again was free.viiHark! – a signal gun – another!On the deck a man appearsStately as the Ocean-shaker —"Ye Athenians, lend your ears!Thomas Wyse am I, a heraldCome to parley with the Greek;Palmerston hath sent me hither,In his awful name I speak —Ye have done a deed of folly – one that ye shall sorely rue!Wherefore did ye lay a finger on the carpets of the Jew?viii"Don Pacifico of Malta!Dull indeed were Britain's ear,If the wrongs of such a heroTamely she could choose to hear!Don Pacifico of Malta!Knight-commander of the Fleece —For his sake I hurl defianceAt the haughty towns of Greece.Look to it – For by my head! since Xerxes crossed the strait,Ye never saw an enemy so vengeful at your gate.ix"Therefore now, restore the carpets,With a forfeit twenty-fold;And a goodly tribute offerOf your treasure and your goldSapienza and the isletCervi, ye shall likewise cede,So the mighty gods have spoken,Thus hath Palmerston decreed!Ere the sunset, let an answer issue from your monarch's lips;In the mean time, I have orders to arrest your merchants' ships."xThus he spoke, and snatched a trumpetSwiftly from a soldier's hand,And therein he blew so shrilly,That along the rocky strandRang the war-note, till the echoesFrom the distant hills replied,Hundred trumpets wildly wailing,Poured their blast on every side;And the loud and hearty shout of Britain rent the skies,"Three cheers for noble Palmerston! another cheer for Wyse!"xiGentles! I am very sorryThat I can not yet relate,Of this gallant expedition,What has been the final fate.Whether Athens was bombardedFor her Jew-coercing crimes,Hath not been as yet reportedIn the columns of the Times.But the last accounts assure us of some valuable spoil:Various coasting vessels, laden with tobacco, fruit, and oil.xiiAncient chiefs! that sailed with JasonO'er the wild and stormy waves —Let not sounds of later triumphsStir you in your quiet graves!Other Argonauts have venturedTo your old Hellenic shore,But they will not live in storyLike the valiant men of yore.O! 'tis more than shame and sorrow thus to jest upon a themeThat for Britain's fame and glory, all would wish to be dream!MONTHLY RECORD OF CURRENT EVENTS

THE NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE will present monthly a digest of all Foreign Events, Incidents, and Opinions, that may seem to have either interest or value for the great body of American readers. Domestic intelligence reaches every one so much sooner through the Daily and Weekly Newspapers, that its repetition in the pages of a Monthly would be dull and profitless. We shall confine our summary, therefore, to the events and movements of foreign lands.

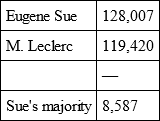

The Affairs of France continue to excite general interest. The election of member of the Assembly in Paris has been the great European event of the month. The Socialists nominated Eugene Sue; their opponents, M. Leclerc. The first is known to all the world as a literary man of great talent, personally a profligate – wealthy, unprincipled, and unscrupulous. The latter was a tradesman, distinguished for nothing but having fought and lost a son at the barricades, and entirely unqualified for the post for which he had been put in nomination. The contest was thus not so much a struggle between the men, as the parties they represented; and those parties were not simply Socialists and Anti-Socialists. Each party included more than its name would imply. The Socialists in Paris are all Republicans: it suits the purposes of the Government to consider all Republicans as Socialists, inasmuch as it gives them an admirable opportunity to make war upon Republicanism, while they seem only to be resisting Socialism. In this adroit and dangerous manner Louis Napoleon was advancing with rapid strides toward that absolutism – that personal domination independent of the Constitution, which is the evident aim of all his efforts and all his hopes. He had gone on exercising the most high-handed despotism, and violating the most explicit and sacred guarantees of the Constitution. He had forbidden public meetings, suppressed public papers, and outraged private rights, with the most wanton disregard of those provisions of the Constitution by which they are expressly guaranteed. The nomination of Eugene Sue was a declaration of hostility to this unconstitutional dynasty. He was supported not only by the Socialists proper, but by all citizens who were in favor of maintaining the Republic with its constitutional guarantees. The issue was thus between a Republic and a Monarchy, between the Constitution and a Revolution. For days previous to the election this issue was broadly marked, and distinctly recognized by all the leading royalist journals, and the Republic was attacked with all the power of argument and ridicule. Repressive laws, and a stronger form of government, which should bridle the fierce democracy, were clamorously demanded. The very day before the polls were opened, the Napoleon journal, which derives its chief inspiration from the President, drew a colored parallel between the necessities of the 18th Brumaire, and those of the present crisis, and entered into a labored vindication of all the arbitrary measures which followed Bonaparte's dissolution of the Assembly, and his usurpation of the executive power. The most high-handed expedients were resorted to by the ministry to assure the success of the coalition. The sale of all the principal democratic journals in the streets was interdicted. The legal prosecutions of the Procureur General virtually reestablished the censorship of the Press. Placards in favor of the democratic candidate were excluded from the street walls, while those of his opponent were every where emblazoned. Electoral meetings were prohibited; democratic merchants and shop-keepers were threatened with a loss of patronage; and the whole republican party was officially denounced as a horde of imbeciles, and knaves, and fanatics. No means were left unemployed by the reactionists to secure a victory.

It was all in vain. On closing the polls the vote stood thus:

And, what is still more startling, four-fifths of all the votes given by the Army were cast for Sue. The result created a good deal of alarm in Paris. Stocks fell, and there seemed to be a general apprehension of an outbreak. If any such event occurs, however, it will be through the instigation of the Government. Finding himself outvoted, Louis Napoleon would undoubtedly be willing to try force. In any event, we do not believe it will be found possible to overthrow Republicanism in France.

Previous to the election there was a Mutiny in the 11th Infantry. On the march of the 2d battalion from Rennes to Toulon, on the 11th April, the popular cry was raised by the common soldiers, urged on by the democrats of the town, and they insulted their officers. At Angers the men were entertained at a fete; and in the evening the soldiers and subaltern officers, accompanied by their entertainers, paraded the streets, shouting again and again, "Vive la République démocratique et sociale!" The Minister of War, on receiving intelligence of this affair, ordered the battalion to be disbanded, and the subalterns and soldiers drafted into the regiments at Algiers.

Besides this disgrace, an involuntary and Appalling Calamity befell this regiment. When the 3d battalion was leaving Angers, on the 16th, at eleven o'clock in the morning they met a squadron of hussars coming from Nantes, which crossed over the suspension-bridge of the Basse Maine, without any accident. A fearful storm raged at the time. The last of the horses had scarcely crossed the bridge than the head of the column of the third battalion of the 11th appeared on the other side. Reiterated warnings were given to the troops to break into sections, as is usually done, but, the rain falling heavily, it was disregarded, and they advanced in close column. The head of the battalion had reached the opposite side – the pioneers, the drummers, and a part of the band were off the bridge, when a horrible crash was heard; the cast-iron columns of the right bank suddenly gave way, crushing beneath them the rear of the fourth company, which, with the flank company, had not stepped upon the bridge. To describe the frightful spectacle, and the cries of despair which were raised, is impossible. The whole town rushed to the spot to give assistance. In spite of the storm, all the boats that could be got at were launched to pick up the soldiers in the river, and a great number who were clinging to the parapets of the bridge, or who were afloat by their knapsacks, were immediately got out. The greater number were, however, found to be wounded by the bayonets, or by the fragments of the bridge falling on them. As the soldiers were got out, they were led into the houses adjoining, and every assistance given. A young lieutenant, M. Loup, rendered himself conspicuous for his heroic exertions; and a young workwoman, at the imminent danger of her life, jumped into the water, and saved the life of an officer who was just sinking. A journeyman hatter stripped and jumped into the river, and, by his strength and skill in swimming, saved a great many lives. One of the soldiers who had reached the shore unhurt, immediately stripped, and swam to the assistance of his comrades. The lieutenant-colonel, an old officer of the empire, was taken out of the river seriously wounded, but remained to watch over the rescue of his comrades. It appears that some people of the town were walking on the bridge at the time of the accident, for among the bodies found were those of a servant-maid and two children.

When the muster-roll was called, it was found that there were 219 soldiers missing, whose fate was unknown. There were, besides, 33 bodies lying in the hospital, and 30 wounded men; 70 more bodies were found during the morning, 4 of whom were officers.

M. Proudhon was arrested on the 18th, and sent to the fortress of Doullens, for having charged the ministry in his own paper, the "Voix du Peuple," with having occasioned the disaster of Angers by sending the 11th Regiment of Light Infantry to Africa. In a letter from prison he acquitted the government of design in producing the catastrophe, but in a tone which hinted the possibility of so diabolical a crime having been meditated.

A Notorious Murderer has been arrested in France, whose mysterious and criminal career would afford the materials for a romance. He was taken at Ivry; in virtue of a writ granted by the President, on the demand of the Sardinian government, having been condemned for a murder under extraordinary circumstances. He was arrested in 1830, at Chambery, his native town, for being concerned in a murder; but he escaped from the prison of Bonneville, where he was confined, and by means of a disguise succeeded in reaching the town of Chene Tonnex, where he went to an inn which was full of travelers. There being no vacant beds, the innkeeper allowed him to sleep in a room with a cattle-dealer, named Claude Duret. The unfortunate cattle-dealer was found dead in the morning, he having been smothered with the mattress on which he had slept. He had a large sum of money with him, which was stolen, and this, as well as his papers, had, no doubt, been taken by Louis Pellet, who had disappeared. Judicial inquiries ensued, and the result was that Louis Pellet, already known to have committed a murder, was condemned, par contumace, to ten years' imprisonment at the galleys by the senate of Chambery. In the mean time Louis Pellet, profiting by the papers of the unfortunate Claude Duret, contrived to reach Paris, when he opened a shop, where he organized a foreign legion for Algeria, enrolled himself under the name of his victim, and sailed for Oran in a government vessel. From this time up to 1834 all trace of him was lost. He came to Paris, took a house, amassed a large sum of money, and it turns out he was mixed up with a number of cases of murder, swindling, and forgery. These facts came to the knowledge of the police, owing to Pellet having been taken before the Correctional Police for a trifling offense, when he appealed against the punishment of confinement for five days. The French government immediately sent an account of the arrest of this great criminal to the consul of the government of Savoy resident at Paris.

Political movements in England are not without interest and importance, although nothing startling has occurred. The birth of another Prince, christened Arthur, has furnished another occasion for evincing the attachment of the English people to their sovereign. The event, which, occurred on the 28th of April, was celebrated by the usual demonstrations of popular joy. Few years will elapse, however, before each of the princes and princesses, whose advent is now so warmly welcomed, will require a splendid and expensive establishment, which will add still more to the burdens of taxation which already press, with overwhelming weight, upon the great mass of the English people. Thus it is that every thing in that country, however fortunate and welcome it may appear, tends irresistibly to an increase of popular burdens which infallibly give birth to popular discontents.

The attention of Parliament has been attracted of late, in an unusual degree, to the intellectual wants of the humbler classes, and to the removal, by legislation, of some of the many restrictions which now deprive them of all access even to the most ordinary sources of information. Even newspapers, which in this country go into the hands of every man, woman, and child who can read, and which therefore enable every member of the community to keep himself informed concerning all matters of interest to him as a citizen, are virtually prohibited to the poorer classes in England by the various duties which are imposed upon them, and which raise the price so high as to be beyond their reach. Mr. Gibson, in the House of Commons, brought forward resolutions, on the 16th of April, to abolish what he justly styled these Taxes on Knowledge: they proposed 1st, to repeal the excise duty only on paper; 2d, to abolish the stamp, and 3d, the advertisement duty on newspapers; 4th, to do away with the customs duty on foreign books. In urging these measures Mr. Gibson said, that the sacrifice of the small excise duty on paper yearly, would lead to the employment of 40,000 people in London alone. The suppression of Chambers' Miscellany, and the prevented re-issue of Mr. Charles Knight's Penny Cyclopædia, from the pressure of the duty, were cited as gross instances of the check those duties impose on the diffusion of knowledge. Mr. Gibson did not propose to alter the postal part of the newspaper stamp duties; all the duty paid for postage – a very large proportion – would therefore still be paid. He dwelt on the unjust Excise caprices which permit this privilege to humorous and scientific weekly periodicals, but deny it to the avowed "news" columns of the daily press. He especially showed by extracts from a heap of unstamped newspapers, that great evil is committed on the poorest reading classes, by denying them that useful fact and true exposition which would be the best antidote to the pernicious principles now disseminated among them by the cheap, unstamped press. There is no reason but this duty, which only gives £350,000 per annum, why the poor man should not have his penny and even his halfpenny newspaper, to give him the leading facts and the important ideas of the passing time. The tax on advertisements checks information, fines poverty, mulcts charity, depresses literature, and impedes every species of mental activity, to realize £150,000 per annum. That mischievous tax on knowledge, the duty on foreign books, is imposed for the sake of no more than £8000 a year! Mr. Gibson concluded by expressing his firm conviction, that unless these taxes were removed, and the progress of knowledge by that and every other possible means facilitated, evils most terrible would arise in the future – a not unfit retribution for the gross impolicy of the legislature. He was supported by Mr. Roebuck, but the motion was negatived, 190 to 89. In his speech he instanced a curious specimen of the manner in which the act is sometimes evaded. A Greenock publisher himself informed him that, having given offense to the authorities by some political reflections in a weekly unstamped newspaper of his of the character of Chambers's Journal, he was prosecuted for violation of the Stamp Act, and fined for each of five numbers £25. Thereupon he diligently studied the Act; and finding that printing upon cloth was not within the prohibition, he set to work and printed his journal upon cloth – giving matter "savoring of intelligence" without the penny stamp – and calling his paper the Greenock Newscloth, sent it forth despite the Solicitor to the Stamp Office.

The Education Bill introduced by Mr. Fox came up on the 17th, and was discussed at some length. The general character of the measure proposed, is very forcibly set forth in an article from the Examiner, which will be found upon a preceding page of this Magazine. The bill was opposed mainly by Lord Arundel, a Catholic, on the ground that it made no provision for religious education, and secular education he denounced as essentially atheistic. Mr. Roebuck advocated the bill in an able and eloquent speech, urging the propriety of education as a means of preventing crime. He asked for the education of the people, and he asked it upon the lowest ground. As a mere matter of policy, the state ought to educate the people; and why did he say so? Lord Ashley had been useful in his generation in getting up Ragged Schools. It was a great imputation upon the kingdom that such schools were needed. Why were they needed? Because of the vice which was swarming in all our great cities. "We pass laws," said he, "send forth an army of judges and barristers to administer them, erect prisons and place aloft gibbets to enforce them; but religious bigotry prevents the chance of our controlling the evil at the source, by so teaching the people as to prevent the crimes we strive to punish." It was because he believed that prevention was better than cure; it was because he believed that the business of government was to prevent crime in every possible way rather than to punish it after its commission, that he asked the house to divest themselves of all that prejudice and bigotry which was at the bottom of the opposition to this measure. The bill was warmly opposed, however, and its further consideration was postponed until the 20th of May.