полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine. No. XVI.—September, 1851—Vol. III

From South America there is little of special interest. A Brazilian fleet has made its appearance on the river Plata, but have as yet made no demonstrations from which their designs can be inferred. A blockade of the ports of the Argentine Republic is thought probable. In Chili the approaching elections were the occasion of no little excitement. The right of suffrage is vested in Chilians by birth or naturalization, who possess a certain amount of property or income, are able to read and write, and have attained the age of 25 years, if unmarried, or 21 years, if married. Efforts are made to introduce railroad communication in Chili and Peru. In New Granada, the imposition of a forced loan by Government has occasioned some revolutionary symptoms, confined apparently to the southern provinces. The Panama papers of July 21, hint that any attempt to levy the loan in that city would be the signal of insurrection, "as it was the firm determination of many of the natives, as well as the foreign population, not to allow a soldier to enter the gates of Panama for the purpose of executing the obnoxious decree." The same papers contain accounts of horrible atrocities committed in the revolted provinces. Yet the general condition of the State is represented to be flourishing; the revenue showing a large increase above that of the previous year.

In Jamaica great complaints are made of the deficiency of labor, owing to which, one-third of the produce will be lost, for the want of labor necessary to secure it. Public attention is directed to the free colored population of the United States, of whom it is said "America could supply a hundred thousand of these, every one of whom would be useful as an inhabitant, if he were not valuable as an agriculturist; and if none but the really industrious were engaged to emigrate, we are of opinion that a most valuable addition might be made to the population of Jamaica." A letter from Mr. Clay to a gentleman in London is published, favoring the project, though he fears that considerable difficulty would be experienced in inducing them to emigrate. He also calls the attention of the West Indians to the fact that the Chinese who have been brought to Cuba, and elsewhere, form a very valuable class of laborers. A portion of the Baptist Society having become dissatisfied with their pastor, and being unable to dissolve the connection, attempted to demolish the Mission House and Chapel; but were prevented by the authorities, aided by the military. Twenty-seven of the rioters were tried and convicted, and sentenced to the penitentiary for terms of from three to nine months. The house of the pastor was afterward attacked, and his furniture destroyed.

In Cuba an insurrection broke out in the early part of July at Puerto Principe, in the eastern part of the island. On the 4th a pronunciamiento was issued, signed by three individuals, purporting to be the manifesto of the Liberating Society of Puerto Principe. In the glowing style which seems natural to the Spanish-American race, it sets forth the grievances of the Cubans, which are doubtless but too real; enumerates the resources for resistance at their disposal, among which are the unanimous determination of the Cubans of all colors; aid from the kindred races in South America; sympathy and assistance from the United States; and a climate hostile to European troops. The island of Cuba is therefore declared free and independent; and the islanders affirmed to owe no allegiance except to those who, awaiting the general suffrage of the people, charge themselves with the civil and military command. The report of these proceedings caused great alarm and excitement at Havana; but we have yet no means of forming any decisive opinion as to the extent of the rising. On the one hand, the official bulletins of the Government represent it as a trifling affair which was at once put down; giving full particulars of names, dates, and places. The same mails which bring these dispatches, are loaded down with letters from the same places, and of the same dates, announcing a general rising; that the troops of the Government are every where defeated, and deserting to the popular cause. The Cuban exiles in this country profess to put implicit faith in the reliability of these accounts, which they say are confirmed by secret letters. At present the probability is that the movement has been unsuccessful.

GREAT BRITAINThe American Steamer Baltic arrived at New York August 16, having made the passage in nine days, fourteen hours, and twenty minutes, apparent time; or, adding the difference of time between the ports, in nine days, eighteen hours and forty-five minutes, actual time, This is the shortest passage ever made. In addition to what is stated below, she brings the news of the passage of the Ecclesiastical Titles Bill in the House of Lords, and its receipt of the royal signature; so that it has now become a law.

As the session of Parliament approaches its close, the proceedings begin to assume some features of interest. The bill to alter the form of the oath of abjuration, so as to allow Jews to sit in Parliament passed the Commons with little opposition, its opponents contenting themselves with expressing their abhorrence of the measure, but leaving to the Peers the ungracious task of excluding from the other House members duly chosen, whom that House was anxious to receive; and that by a mere formal test, designed for quite a different purpose. In the Upper House, as was foreseen, the bill was lost. Only two of the bishops took part in the discussion, both of whom were in favor of the bill. Dr. Whately, the distinguished Archbishop of Dublin, advocated the removal of the Jewish disabilities, on the ground that Christianity did not meddle with temporalities; and that the free choice by electors of their representatives should not be interfered with. The Bishop of Norwich considered the restriction to be prejudicial, rather than beneficial to Christianity. Against the bill it was urged that Parliament ought to maintain its Christian character, and that the Jews were of necessity opponents of Christianity. The bill was thrown out by a vote of 144 to 108. Immediately after the rejection, Mr. Salomons, a Jew, who had been elected member from Greenwich, appeared at the bar of the House of Commons, and requested to be sworn on the Old Testament. He took the oaths of allegiance and supremacy as required; but in the oath of abjuration, for the concluding words, "on the true faith of a Christian," he substituted "so help me God." The Speaker decided that he had not taken the oath, as required, and ordered him to retire without the bar of the House. This he did after some delay, amidst a scene of great uproar. At the next meeting he appeared and took his seat within the bar of the House, and proceeded to vote upon three questions that came up; thus rendering himself liable to a penalty of £1500. Amidst great disorder and confusion, he was ordered by a vote of the House, 281 to 81, to withdraw, upon which he was removed by the sergeant-at-arms. Lord John Russell then moved a resolution, similar to that passed last year in the case of Baron Rothschild, that Mr. Salomons was not entitled to sit in the House until he had taken the oath of abjuration according to law. A meeting was subsequently held of the constituents of Baron Rothschild, at which he was requested to persist in claiming his seat. Proceedings have been instituted against Mr. Salomons to recover the penalty incurred by voting in the House. This will bring the whole matter before the legal tribunals. It is contended by some of the ablest counsel that all the essential requirements of the law were complied with, the precise wording of the oath being merely formal.

The Ecclesiastical Titles Bill, which was so ostentatiously put forward as the leading measure of the session, passed through its final stage in the Commons, very tamely, a thin House being present. During the progress of the bill, in spite of the opposition of the Ministers, it had been rendered more stringent by the addition of two clauses; one of which provided that the publication of any bull, brief, rescript, or other Papal document should subject the publisher to a fine of £100; the other clause empowered any informer, with the sanction of the law officers of the Crown, to bring an action for a violation of the provisions of the bill. Lord John Russell moved the omission of these clauses, but was defeated. While this vote was taken, the Irish members left the House, and did not return in time to vote upon the final passage of the bill, which passed by 263 to 46, a majority of 217. Less than one half of the members of the House voted. A motion was made, and lost, that the bill should be entitled "A Bill to prevent the free exercise of the Roman Catholic Religion in Ireland." Mr. Grattan in moving it, said that the Catholics were delighted to see the bill as it was, as they wished it to be as discreditable, as tyrannical, and as unpalatable as it could be made. As the same penalty was attached to the introduction of bulls as to the assumption of titles, they would be able, more or less, to violate the provisions of the bill; and, by the blessing of God, they would violate it as often as possible. Mr. Gladstone, a Tory and High-Churchman, undoubtedly the most able statesman now in Parliament, protested solemnly against the passage of the bill, as hostile to the institutions of the country, and to the Established Church, which it taught to rely upon other support than spiritual strength and vitality; as tending to weaken the authority of law in Ireland; as disparaging the principle of religious freedom; and destroying the bonds of concord and good-will between different classes and persuasions of her Majesty's subjects. In the Upper House the bill passed to a second reading by a vote of 265 to 38; within a single vote of seven to one in its favor. Among those who voted against the bill, we observe the names of Brougham, Aberdeen, and Denman. The Pope has recently filled up several of the bishoprics, in accordance with the decree of Sept. 28, 1850, which occasioned the excitement to which the Ecclesiastical Titles Bill owes its origin.

A bill, making some alterations in the Chancery system, is under discussion. Lord Brougham made a speech upon it, urging the absolute necessity of a thorough reconstruction of that court. It was his last speech for the session, the state of his health compelling him to take his leave. He had struggled to the last, in the hope of assisting in the passage of a measure to which his whole life had been devoted.

Leave has been granted to bring in a bill for the introduction of the ballot into parliamentary elections. The object of the bill is to protect voters from intimidation in the exercise of the franchise; and to diminish the inducements to bribery, by rendering it impossible for the purchaser of a vote to ascertain whether or not the elector has fulfilled his bargain.

Ecclesiastical affairs, in one form or another, awaken no little interest. The Bishop of Exeter's diocesan synod supported that prelate's views, which are opposed to those of the great majority of the Episcopal Bench. The question of a Convocation, to decide upon points in controversy, is agitated; but there is a prevailing apprehension that the result would be any thing but harmonious. A motion was made in the Commons for an address to the Queen, urging the adoption of measures to supply the rapidly increasing spiritual wants of the people. In connection with this motion, some startling charges were made of abuses in the management of the ecclesiastical funds. Some years ago it was determined that the bishops should receive fixed incomes, varying from £4,500 to £15,000 a year; and that the surplus revenues of their sees should be paid over to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, to be expended for Church purposes. It was shown by indisputable statistics, that in a number of instances the bishops had retained more than they were entitled to. Specific charges of a still graver nature were made, that they had used the estates of their bishoprics in such a manner as to benefit themselves and their friends, at the expense of their sees. These charges were shown to be more or less erroneous; but a general impression prevails that the explanations given are far from satisfactory, and that great abuses exist. On the whole, this is regarded as the most severe blow that has yet been aimed at the Establishment.

Lord Palmerston announced in Parliament, that the African slave-trade, north of the Line, was now almost entirely extinct; and the natives who had hitherto been engaged in it, were turning their attention to the traffic in the productions of the country, such as palm-oil, ground-nuts, and ivory. This result he attributed to the vigilance of the English, French, American, and Portuguese cruisers, together with the rapid progress made by the Republic of Liberia. Brazil has heretofore been the principal market for slaves; but owing to the efficient action of the Government, it has been nearly closed within the last few months. He was confident that the suppression of the slave-trade would be permanent, provided the vigilance of the preventive squadrons was kept up for a while longer.

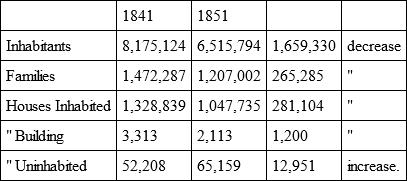

The returns of the Irish census show an amount of depopulation even greater than had been anticipated. The following is a comparison of some of the details with those of the census of 1841:

The decrease in the number of houses is quite as startling a fact as that of the population, and probably represents with tolerable accuracy the number of evictions effected by the demolition of the cabins of the peasantry. The rate of depopulation does not vary very materially in the different sections of the island. The large towns only show any increase, indicating that the evicted peasantry, driven from their former residences, take refuge in the cities. The entire increase of population in the British Islands is but about 600,000. The large cities have increased more than this; so that the number of the rural population of the kingdom is less than it was ten years ago. The population of Ireland in 1821, was 6,801,827; in 1831, 7,667,401; in 1841, 8,175,124; in 1851, 6,515,794; so that it is now nearly 300,000 less than it was thirty years since. The emigration from Ireland during the last ten years, is estimated at about 1,300,000, of which probably 1,000,000 came directly or indirectly to the United States. Considering that the emigrants, to a great extent, are the most active and energetic of the inhabitants, it is safe to conclude that one-third of the effective strength of the island has been transferred across the Atlantic in ten years.

A meeting of authors and publishers was held July 1, to consider the present aspect of the copyright question. Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton presided and made the opening speech. He said that the recent decision of Lord Campbell ruined all prospect of international copyright with France and America, for foreigners would not buy what they could get for nothing. The effect on literature would be disastrous. In America, where they get the works of Macaulay for nothing, they are ceasing, he said, to produce any solid works of their own. Cooper and Irving belong to a past generation, and with the exception of Mr. Prescott none are rising to take their place. A resolution was passed, on the motion of Mr. Bohn, the publisher, to the effect that the decision of Lord Campbell must prove prejudicial to the interests of British literature, because it removes the main inducement for foreign states to consent to an international copyright.

A grand entertainment was given by the Mayor and Corporation of London, July 9, in honor of the Exhibition. It was attended by the Queen in state. Great preparations were made to insure a splendid reception; the streets through which the royal cortège passed were brilliantly illuminated. But the whole entertainment seems to have been a tasteless and fussy affair. Among the wines furnished for the royal table was sherry which had been bottled for the Emperor Napoleon, at a cost of £600 the pipe; it was 105 years old.

Mr. Peabody, a distinguished American banker residing in London, gave a splendid entertainment on the 4th of July, at "Willis's Rooms," the very shrine of the ultra-fashionable world of London, to the American Minister and a large company of English, American, and foreign guests. It was designed to show that this day might be rather a pledge of good-will, than a gage of strife. The most notable incident was the attendance of the Duke of Wellington.

The Exhibition still continues as successful as ever. The receipts already far exceed the £300,000, which was the utmost limit conceived possible a few weeks since. The greatest number of visitors in a single day was on the 15th of July, when they numbered 74,000. At one time there were present 61,000 people, equal to the population of a considerable city. A movement hostile to the permanent retention of the Crystal Palace upon its present site has been commenced, mainly by the owners of property in its vicinity. The clergy resident in the district oppose its continuance on grounds of morality. It has been decided to allow the building to remain during the winter, in order to test its adaptation for a winter garden.

FRANCEThe proposition for a revision of the Constitution failed to secure the requisite majority in the Legislative Assembly, and so was defeated. On the 8th of July the Report of the committee to whom the petitions for a revision were referred, was presented by M. de Tocqueville. It is a document of great length, drawn up with decided ability. After discussing in detail the defects inherent in the constitution, which in the opinion of a majority of the Committee were of sufficient moment to render a revision desirable, the Report proceeds to examine the present situation of the country and the perils which had been alleged to attend the revision, should it now be attempted. These apprehended dangers arose from the unsettled state of the franchise, and the contests of parties, each of whom desires a revision as a means for the accomplishment of its own ends. The majority of the Committee, while admitting the danger attending a revision, are yet convinced that it is exceedingly necessary. This conclusion rests mainly upon the circumstance, adverted to in our last Record, that the functions of the Legislative and of the Executive branches of the Government expire at almost the same time. The intention of the Constitution in fixing the term of the one at four and of the other at three years was to prevent the occurrence of this, until after an interval of twelve years had given stability to the Republic. But by the law of October, 1848, the regular time of the election for President was anticipated, so that his term expires a year sooner than it should have done. Besides this there is the danger that a candidate whom the Constitution renders ineligible may be the one upon whom the popular choice will fix. Such a violation of the Constitution, facilitated by the method of election by direct suffrage which it provides, would be productive of the most fatal consequences. These dangers may be obviated by surrendering the power of Government into the hands of a Constituent Assembly. The Report then goes on to discuss the question of the kind and amount of revision to be recommended. The Committee, however divided upon other points, were unanimously of the opinion that the Legislative Assembly had no power either to propose to the Constituent Assembly that the nation should quit the Republic, or to impose upon it that form of Government. The Constituent would supersede the Legislative Assembly, and must be independent of it. The Committee were also unanimously of the opinion that the revision, if made at all, must be made in the manner prescribed by the Constitution. If the requisite majority of three-fourths of the votes of the Assembly could not be secured in its favor, it must be abandoned; and hence, "any attempt having for its object to urge the people toward unconstitutional candidateship, from the moment that the Constitution can not be legally revised, would not only be improper and irregular, but culpable." The proposition which the Committee, by a vote of 9 to 6, resolved to submit to the Assembly, and to which they asked their consent, was: "Taking into consideration Article 111 of the Constitution, the Assembly decides that the Constitution shall be revised in totality." The reading of this Report was listened to with an attention and decorum by no means characteristic of the French Legislature. At the close, a large number of members inscribed their names, as intending to take part in the discussion. This was done to meet the requirements of the rule that a speaker upon one side succeeds one upon the other. The debate upon this Report commenced on the 14th. It was opened by an admonitory speech from the President of the Assembly, M. Dupin, recommending order and moderation in the discussion. A brief sketch of the views advanced by the principal speakers will serve better than any thing else to show the state of opinion and feeling in France at the present moment. M. de Falloux, formerly Minister of Public Instruction, in an eloquent and impressive speech, urged the re-establishment of the monarchical principle, as the only means of saving the country, which was falling into decay. He said Socialism was rapidly increasing, not merely among the very poor, but also among the better paid class of workmen. M. Cavaignac made a firm and temperate speech against the revision, and in favor of building up a strong republic. M. Coquerel, the well-known Protestant pastor, advocated a revision. He believed that Bonaparte would be elected, whether constitutionally or not, and he preferred that it should be done constitutionally. He defended the republican form of government, and avowed his belief that it would ultimately become universal. M. Michel (de Bourges), who has made himself known as the able counsel for the prosecuted newspapers and proscribed Socialists, made a long and very able speech on the democratic side of the question, and against the revision. He spoke in terms of commendation of the "Girondists who proclaimed the Republic, and of the Montagnards who saved it," and of "the Convention which made the Constitution known to Europe by cannon shots, and delivered the country from tyrants." This speech has been printed by the party for gratuitous distribution, as an exponent of their views. M. de Berryer followed in a brilliant speech in favor of Legitimacy. He admitted the great services which the President had rendered to the cause of order, but deprecated his re-election in spite of the Constitution, by universal suffrage, as he would then be placed in a position superior to the Constitution. This catastrophe was to be averted, if at all by the action of a Constituent Assembly. He painted in glowing colors all the excesses of which the Republic had been guilty, and affirmed that France was not adapted for or in favor of a republican form of government. Victor Hugo followed in a speech in opposition to a revision and to monarchy, and in favor of the Republic. He reflected in very severe terms upon the Government and upon the majority in the Assembly. His speech was greeted with applause from the Left and disapprobation from the Right. The debate, which had hitherto been conducted with great decorum, now closed amid a scene of wild disorder. On the following day, the 19th, the closing speech in the discussion was made by Odillon Barrot in favor of a revision, as the only means of averting the dangers which impended. At the conclusion of his speech, the question was demanded and carried. The whole number of votes cast was 724; of these 446 were in favor of revision, and 278 against it. Three-fourths of the votes cast, the number required to carry the proposition, is 543; so that it failed by 97 votes. By the rules of the Assembly it can not be revived until after an interval of three months. The absorbing interest of the occasion is shown by the large vote cast. The Assembly, when full, consists of 750 members; there are now 14 vacancies, so that only 12 members were absent. The vote against the revision was made up of the extreme Republicans in a mass, with a few of almost every shade of opinion; including Thiers and his friends, Lamartine, and a considerable body of moderate Republicans, as well as a few Legitimists.