полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol III, No 13, 1851

"A life of unblemished honor," replied his friend, "has placed you above the reach of suspicion; besides, look here!" And he showed the missing watch. "It is I," continued he, "who must ask pardon of you all. In a fit of absence I had dropped it into my waistcoat pocket, where, in Johnson's presence, I discovered it while undressing."

"If I had only known!" murmured poor Dutton.

"Don't regret what has occurred," said the general, pressing his hand kindly. "It has been the means of acquainting me with what you should never have concealed from an old friend, who, please God, will find some means to serve you."

In a few days Captain Dutton received another invitation to dine with the general. All the former guests were assembled, and their host, with ready tact, took occasion to apologize for his strange forgetfulness about the watch. Captain Dutton found a paper within the folds of his napkin: it was his nomination to an honorable and lucrative post, which insured competence and comfort to himself and his family.

NEW PROOF OF THE EARTH'S ROTATION

"The earth does move notwithstanding," whispered Galileo, leaving the dungeon of the Inquisition: by which he meant his friends to understand, that if the earth did move, the fact would remain so in spite of his punishment. But a less orthodox assembly than the conclave of Cardinals might have been staggered by the novelty of the new philosophy. According to Laplace, the apparent diurnal phenomena of the heavens would be the same either from the revolution of the sun or the earth; and more than one reason made strongly in favor of the prevalent opinion that the earth, not the sun, was stationary. First, it was most agreeable to the impression of the senses; and next, to disbelieve in the fixity of the solid globe, was not only to eject from its pride of place our little planet, but to disturb the long-cherished sentiment that we ourselves are the centre – the be-all and end-all of the universe. However, the truth will out; and this is its great distinction from error, that while every new discovery adds to its strength, falsehood is weakened and at last driven from the field.

That the earth revolves round the sun, and rotates on its polar axis, have long been the settled canons of our system. But the rotation of the earth has been rendered visible by a practical demonstration, which has drawn much attention in Paris, and is beginning to excite interest in this country. The inventor is M. Foucault; and the following description has been given of the mode of proof:

"At the centre of the dome of the Panthéon a fine wire is attached, from which a sphere of metal, four or five inches in diameter, is suspended so as to hang near the floor of the building. This apparatus is put in vibration after the manner of a pendulum. Under and concentrical with it, is placed a circular table, some twenty feet in diameter, the circumference of which is divided into degrees, minutes, &c., and the divisions numbered. Now, supposing the earth to have the diurnal motion imputed to it, and which explains the phenomena of day and night, the plane in which this pendulum vibrates will not be affected by this motion, but the table over which the pendulum is suspended will continually change its position in virtue of the diurnal motion, so as to make a complete revolution round its centre. Since, then, the table thus revolves, and the pendulum which vibrates over it does not revolve, the consequence is, that a line traced upon the table by a point projecting from the bottom of the ball will change its direction relatively to the table from minute to minute and from hour to hour, so that if such point were a pencil, and that paper were spread upon the table, the course formed by this pencil would form a system of lines radiating from the centre of the table. The practiced eye of a correct observer, especially if aided by a proper optical instrument, may actually see the motion which the table has in common with the earth under the pendulum between two successive vibrations. It is, in fact, apparent that the ball, or rather the point attached to the bottom of the ball, does not return precisely to the same point of the circumference of the table after two successive vibrations. Thus is rendered visible the motion which the table has in common with the earth."

Crowds are said to flock daily to the Panthéon to witness this interesting experiment. It has been successfully repeated at the Russell Institution, and preparations are being made in some private houses for the purpose. A lofty staircase or room twelve or fourteen feet high would suffice; but the dome of St. Paul's, or, as suggested by Mr. Sylvestre in the Times, the transept of the Crystal Palace, offers the most eligible site. The table would make its revolution at the rate of 15° per hour. Explanations, however, will be necessary from lecturers and others who give imitations of M. Foucault's ingenuity, to render it intelligible to those unacquainted with mathematics, or with the laws of gravity and spherical motion. For instance, it will not be readily understood by every one why the pendulum should vibrate in the same plane, and not partake of the earth's rotation in common with the table; but this could be shown with a bullet suspended by a silk-worm's thread. Next, the apparent horizontal revolution of the table round its centre will be incomprehensible to many, as representative of its own and the earth's motion round its axis. Perhaps Mr. Wyld's colossal globe will afford opportunities for simplifying these perplexities to the unlearned.

The pendulum is indeed an extraordinary instrument, and has been a useful handmaid to science. We are familiar with it as the time-regulator of our clocks, and the ease with which they may be made to go faster or slower by adjusting its length. But neither this nor the Panthéon elucidation constitutes its sole application. By it the latitude maybe approximately ascertained, the density of the earth's strata in different places, and its elliptical eccentricity of figure. The noble Florentine already quoted was its inventor; and it is related of Galileo, while a boy, that he was the first to observe how the height of the vaulted roof of a church might be measured by the times of the vibration of the chandeliers suspended at different altitudes. Were the earth perforated from London to our antipodes, and the air exhausted, a ball dropped through would at the centre acquire a velocity sufficient to carry it to the opposite side, whence it would again descend, and so oscillate forward and backward from one side of the globe's surface to the other in the manner of a pendulum. Very likely the Cardinals of the Vatican would deem this heresy, or "flat blasphemy."

To clearly appreciate the following popular explanation, it will be necessary for the reader to convince himself of one property of the pendulum, viz., that of constantly vibrating in the same plane. Let it be imagined that a pendulum is suspended over a common table, the parts bearing the pendulum being also attached to the table. Suppose, also, that the table can move freely on its centre like a music-stool: the pendulum being put in motion will continue to move in the same plane between the eye and any object on the walls of the room, although the table is made to revolve, and during one revolution will have radiated through the whole circumference. A few moments' reflection are only necessary to prove this.

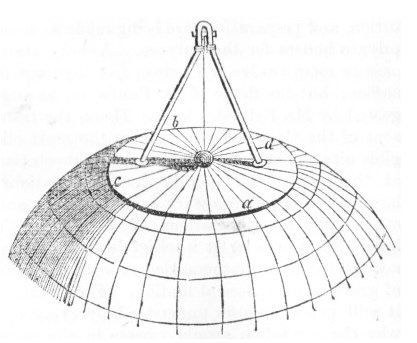

FIGURE 1.

The above figure represents a plane or table on the top of a globe, or at the north pole of the earth. To this table are fixed two rods, from which is suspended a pendulum, moving freely in any direction. The pendulum is made to vibrate in the path a b; it will continue to vibrate in this line, and have no apparent circular or angular motion until the globe revolves, when it will appear to have vibrated through the entire circle, to an object fixed on the table and moving with it. It is scarcely necessary to say the circular motion of the pendulum is only apparent, since it is the table that revolves – the apparent motion of the pendulum in a circle being the same as the apparent motion of the land to a person on board ship, or the recession of the earth to a person in a balloon. The pendulum vibrates always in the same plane at the pole, and in planes parallel to each other at any intermediate point.

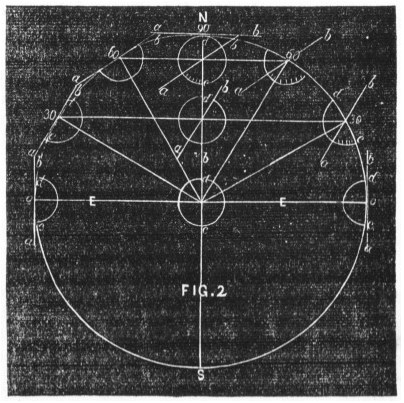

Fig. 2 represents the earth or a globe revolving once in twenty-four hours on its axis (s n). It is divided, on its upper half, by lines parallel to each other, representing the latitudes 60 degrees, 30 degrees, and the equator, where the latitude is nothing. The lines a b, at 90, 60, 30, and 0 represent the planes of those latitudes; or, in more familiar terms, tables, over which a pendulum is supposed to vibrate, and moving with them in their revolutions round the axis (s n). This being clearly understood, the next object is to show how the pendulum moves round the tables, for each of the latitudes; also to show the gradual diminution of its circular motion as it approaches the equator (e e), where, as was before observed, the latitude is nothing.

A pendulum vibrating over the plane, or table (a b), on the top of the globe, has been already shown (by Fig. 1) to go round the entire circle in twenty-four hours; or to have an angular velocity of 90, or quarter of a circle, in six hours. The plane (a b), at 60, has an inclination to the axis (s n), which will cause a pendulum vibrating over it to move through its circumference at a diminished rate. This will be shown by reference to the figure. The globe is revolving in the direction from left to right; the pendulum is vibrating over the line a b, which, at all times during its course, is parallel with the first path of vibration. The plane may now be supposed to have moved during six hours, or to have gone through a quarter of an entire revolution, equal to 90; but the pendulum has only moved from c to a, considerably less than 90. Again, if the plane is carried another six hours, making together 180, the Figure shows the pendulum to have moved only from c to a, considerably less than 180. The same remarks apply to the lower latitude of 30, where, it will be seen, the circular, or angular motion of the pendulum, is considerably slower than in the latitude of 60, continuing to diminish, until it becomes nothing at the equator, where it is clearly shown by the Figure to be always parallel to itself, and constant over its path of vibration through the entire circle.

ADVENTURE WITH A GRIZZLY BEAR. 12

I now took a long farewell of the horses, and turned northward, selecting a line close in by the base of the hills, going along at an improved pace, with a view of reaching the trading-post the same night; but stopping in a gully to look for water, I found a little pool, evidently scratched out by a bear, as there were foot-prints and claw-marks about it; and I was aware instinct prompts that brute where water is nearest the surface, when he scratches until he comes to it. This was one of very large size, the foot-mark behind the toes being full nine inches; and although I had my misgivings about the prudence of a tête-à-tête with a great grizzly bear, still the "better part of valor" was overcome, as it often is, by the anticipated honor and glory of a single combat, and conquest of such a ferocious beast. I was well armed, too, with my favorite rifle, a Colt's revolver, that never disappointed me, and a non-descript weapon, a sort of cross betwixt a claymore and a bowie-knife; so, after capping afresh, hanging the bridle on the horn of the saddle, and, staking my mule, I followed the trail up a gully, and much sooner than I expected came within view and good shooting distance of Bruin, who was seated erect, with his side toward me, in front of a manzanita bush, making a repast on his favorite berry.

The sharp click of the cock causing him to turn quickly round, left little time for deliberation; so, taking a ready good aim at the region of the heart, I let drive, the ball (as I subsequently found) glancing along the ribs, entering the armpit, and shattering smartly some of the shoulder bones. I exulted as I saw him stagger and come to his side; the next glance, however, revealed him, to my dismay, on all fours, in direct pursuit, but going lame; so I bolted for the mule, sadly encumbered with a huge pair of Mexican spurs, the nervous noise of the crushing brush close in my rear convincing me he was fast gaining on me; I therefore dropped my rifle, putting on fresh steam, and reaching the rope, pulled up the picket-pin, and springing into the saddle with merely a hold of the lariat, plunged the spurs into the mule, which, much to my affright produced a kick and a retrograde movement; but in the exertion having got a glimpse of my pursuer, uttering; snort of terror, he went off at a pace I did not think him capable of, soon widening the distance betwixt us and the bear; but having no means of guiding his motions, he brought me violently in contact with the arm of a tree, which unhorsed and stunned me exceedingly. Scrambling to my feet as well as I could, I saw my relentless enemy close at hand, leaving me the only alternative of ascending a tree; but, in my hurried and nervous efforts, I had scarcely my feet above his reach, when he was right under, evidently enfeebled by the loss of blood, as the exertion made it well out copiously. After a moment's pause, and a fierce glare upward from his blood-shot eyes, he clasped the trunk; but I saw his endeavors to climb were crippled by the wounded shoulder. However, by the aid of his jaws, he just succeeded in reaching the first branch with his sound arm, and was working convulsively to bring up the body, when, with a well-directed blow from my cutlass, I completely severed the tendons of the foot, and he instantly fell with a dreadful souse and horrific growl, the blood spouting up as if impelled from a jet; he rose again somewhat tardily, and limping round the tree with upturned eyes, kept tearing off the bark with his tusks. However, watching my opportunity, and leaning downward, I sent a ball from my revolver with such good effect immediately behind the head, that he dropped; and my nerves being now rather more composed, I leisurely distributed the remaining five balls in the most vulnerable parts of his carcase.

By this time I saw the muscular system totally relaxed, so I descended with confidence, and found him quite dead, and myself not a little enervated with the excitement and the effects of my wound, which bled profusely from the temple; so much so, that I thought an artery was ruptured. I bound up my head as well as I could, loaded my revolver anew, and returned for my rifle; but as evening was approaching, and my mule gone, I had little time to survey the dimensions of my fallen foe, and no means of packing much of his flesh. I therefore hastily hacked off a few steaks from his thigh, and hewing off one of his hind feet as a sure trophy of victory, I set out toward the trading-post, which I reached about midnight, my friend and my truant mule being there before me, but no horses.

I exhibited the foot of my fallen foe in great triumph, and described the conflict with due emphasis and effect to the company, who arose to listen; after which I made a transfer of the flesh to the traders, on condition that there was not to be any charge for the hotel or the use of the mule. There was an old experienced French trapper of the party, who, judging from the size of the foot, set down the weight of the bear at 1500 lbs., which, he said they frequently over-run, he himself, as well as Colonel Frémont's exploring party, having killed several that came to 2000 lbs. He advised me, should I again be pursued by a bear, and have no other means of escape, to ascend a small-girthed tree, which they can not get up, for, not having any central joint in the fore-legs, they can not climb any with a branchless stem that does not fully fill their embrace; and in the event of not being able to accomplish the ascent before my pursuer overtook me, to place my back against it, when, if it and I did not constitute a bulk capable of filling his hug, I might have time to rip out his entrails before he could kill me, being in a most favorable posture for the operation. They do not generally use their mouth in the destruction of their victims, but, hugging them closely, lift one of the hind-feet, which are armed with tremendous claws, and tear out the bowels. The Frenchman's advice reads rationally enough, and is a feasible theory on the art of evading unbearable compression; but, unfortunately, in the haunts of that animal those slim juvenile saplings are rarely met with, and a person closely confronted with such a grizzly vis-à-vis is not exactly in a tone of nerve for surgical operations.

A VISIT TO THE NORTH CAPE

Having hired an open boat and a crew of three hands, I left Hammerfest at nine p. m., July 2, 1850, to visit the celebrated Nordkap. The boat was one of the peculiar Nordland build – very long, narrow, sharp, but strongly built, with both ends shaped alike, and excellently adapted either for rowing or sailing. We had a strong head-wind from northeast at starting, and rowed across the harbor to the spot where the house of the British consul, Mr. Robertson, a Scotchman, is situated, near to the little battery (fæstning) which was erected to defend the approach to Hammerfest, subsequently to the atrocious seizure of the place by two English ships during the last war. Mr. Robertson kindly lent me a number of reindeer skins to lie on at the bottom of the boat; and spreading them on the rough stones we carried for ballast, I was thus provided with an excellent bed. I have slept for a fortnight at a time on reindeer skins, and prefer them to any feather bed. Mr. Robertson warned me that I should find it bitterly cold at sea, and expressed surprise at my light clothing; but I smiled, and assured him that my hardy wandering life had habituated me to bear exposure of every kind with perfect impunity. By an ingenious contrivance of a very long tiller, the pilot steered with one hand and rowed with the other, and we speedily cleared the harbor, and crept round the coast of Qual Oe (Whale-Island), on which Hammerfest is situated. About midnight, when the sun was shining a considerable way above the horizon, the view of a solitary little rock, in the ocean ahead, bathed in a flood of crimson glory, was most impressive. We proceeded with a tolerable wind until six in the morning, when heavy squalls of wind and torrents of rain began to beat upon us, forcing us to run, about two hours afterward, into Havösund; a very narrow strait between the island of Havöe and the mainland of Finmark. As it was impossible to proceed in such a tempest, we ran the boat to a landing-place in front of the summer residence of Herr Ulich, a great magnate in Finmark. This is undoubtedly the most northern gentleman's house in the world. It is a large, handsome, wooden building, painted white, and quite equal in appearance to the better class of villas in the North. The family only reside there during the three summer months; and extensive warehouses for the trade in dried cod or stockfish, &c. are attached. My crew obtained shelter in an outbuilding, and I unhesitatingly sought the hospitality of the mansion. Herr Ulich himself was absent, being at his house at Hammerfest, but his amiable lady, and her son and two daughters, received me with a frank cordiality as great as though I were an old friend; and in a few minutes I was thoroughly at home. Here I found a highly accomplished family, surrounded with the luxuries and refinements of civilization, dwelling amid the wildest solitudes, and so near the North Cape, that it can be distinctly seen from their house in clear weather. Madame Ulich and her daughters spoke nothing but Norwegian; but the son, a very intelligent young man of about nineteen, spoke English very well. He had recently returned from a two years' residence at Archangel, where the merchants of Finmark send their sons to learn the Russian language, as it is of vital importance for their trading interests – the greater portion of the trade of Finmark being with the White-Sea districts, which supply them with meal and other necessaries in exchange for stockfish, &c. Near as they were to the North Cape, it was a singular fact that Herr Ulich and his son had only once visited it; and the former had resided ten years at Havösund – not more than twenty-five miles distant – ere that visit took place! They said that very few travelers visited the Cape; and, strange to say, the majority are French and Italians.

I declined to avail myself of the pressing offer of a bed, and spent the morning in conversation with this very interesting family. They had a handsome drawing-room, containing a grand colossal bust in bronze of Louis-Philippe, King of the French. The ex-king, about fifty-five years ago, when a wandering exile (under the assumed name of Müller) visited the North Cape. He experienced hospitality from many residents in Finmark, and he had slept in this very room; but the house itself then stood on Maas Island, a few miles further north. Many years ago, the present proprietor removed the entire structure to Havöe; and his son assured me the room itself was preserved almost exactly as it was when Louis Philippe used it, though considerable additions and improvements have been made to other parts of the house. About sixteen years ago, Paul Garnard, the president of the commission shortly afterward sent by the French government to explore Greenland and Iceland, called on Herr Ulich, and said he was instructed by the king to ask what present he would prefer from his majesty as a memorial of his visit to the North. A year afterward, the corvette of war, La Recherche, on its way to Iceland, &c. put into Havösund, and left the bust in question, as the express gift of the king. It is a grand work of art, executed in the finest style, and is intrinsically very valuable, although of course the circumstances under which it became Herr Ulich's property add inestimably to its worth in his eyes. The latter gentleman is himself a remarkable specimen of the highly-educated Norwegian. He has traveled over all Europe, and speaks, more or less, most civilized languages. On my return to Hammerfest I enjoyed the pleasure of his society, and his eager hospitality; and he favored me with an introduction for the Norwegian states minister at Stockholm. I merely mention these things to show the warm-hearted kindness which even an unintroduced, unknown traveler may experience in the far North. Herr Ulich has resided twenty-five years at Havösund; and he says he thinks that not more than six English travelers have visited the North Cape within twenty years – that is to say, by way of Hammerfest; but parties of English gentlemen occasionally proceed direct in their yachts.

Fain would my new friends have delayed my departure; but, wind and tide serving, I resumed my voyage at noon, promising to call on my return. In sailing through the sound, I noticed a neat little wooden church, the most northern in Finmark. A minister preaches in it to the Fins and Laps at intervals, which depend much on the state of the weather; but I believe once a month in summer. The congregation come from a circle of immense extent. If I do not err, Mr. Robert Chambers mentions in his tour having met with the clergyman of this wild parish.

Passing Maas Oe, we sailed across an open arm of the sea, and reached the coast of Mager Oe, the island on which the North Cape is situated. Mager Oe is perhaps twenty miles long by a dozen broad, and is separated from the extreme northern mainland of Finmark by Magerösund. Although a favorable wind blew, my crew persisted in running into a harbor here, where there is a very extensive fish-curing establishment, called Gjesvohr, belonging to Messrs Agaard of Hammerfest. There are several houses, sheds, &c. and immense tiers of the split stockfish drying across horizontal poles. At this time about two hundred people were employed, and one or two of the singular three-masted White-Sea ships were in the harbor, with many Finmark fishing-boats. The water was literally black with droves of young cod, which might have been killed by dozens as they basked near the surface. My men loitered hour after hour; but as I was most anxious to visit the North Cape when the midnight sun illumined it, I induced them to proceed.