полная версия

полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, No. VII, December 1850, Vol. II

In the City of New York, meantime, there had been a growing feeling of apprehension at the tone of current political discussions and at the opposition everywhere manifested at the North to the Fugitive Slave Law, and on the 30th of October a very large public meeting was held at Castle Garden of those who were in favor of sustaining all the peace measures of Congress, and of taking such measures as would prevent any further agitation of the question of slavery. Mr. George Wood, an eminent member of the New York Bar, presided. A letter was read from Mr. Webster, to whom the resolutions intended to be brought forward had been sent, with an invitation to attend the meeting. The invitation was declined, but Mr. Webster expressed the most cordial approbation of the meeting, and of its proposed action. He concurred in "all the political principles contained in the resolutions, and stood pledged to support them, publicly and privately, now and always, to the full extent of his influence, and by the exertion of every faculty which he possessed." The Fugitive Slave Law he said, was not such a one as he had proposed, and should have supported if he had been in the Senate. But it is now "the law of the land, and as such is to be respected and obeyed by all good citizens. I have heard," he adds, "no man, whose opinion is worth regarding, deny its constitutionality; and those who counsel violent resistance to it, counsel that, which, if it take place, is sure to lead to bloodshed, and to the commission of capital offenses. It remains to be seen how far the deluded and the deluders will go in this career of faction, folly, and crime. No man is at liberty to set up, or to affect to set up, his own conscience as above the law, in a matter which respects the rights of others, and the obligations, civil, social, and political, due to others from him. Such a pretense saps the foundation of all government, and is of itself a perfect absurdity; and while all are bound to yield obedience to the laws, wise and well-disposed citizens will forbear from renewing past agitation, and rekindling the names of useless and dangerous controversy. If we would continue one people, we must acquiesce in the will of the majority, constitutionally expressed; and he that does not mean to do that, means to disturb the public peace, and to do what he can to overturn the Government." The resolutions adopted at the meeting, declared the purpose "to sustain the Fugitive Slave Law and its execution by all lawful means: " and that those represented at the meeting would "support no candidate at the ensuing or any other election, for state officers, or for members of Congress or of the Legislature, who is known or believed to be hostile to the peace measures recently adopted by Congress, or any of them, or in favor of re-opening the questions involved in them, for renewed agitation."

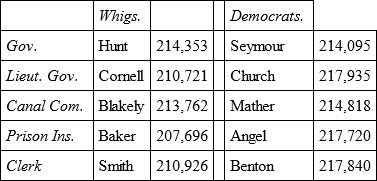

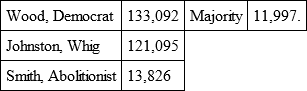

This meeting was followed by the nomination of a ticket, intended to represent these views, and those candidates only were selected, from both the party nominees, who were known or believed to entertain them. Mr. Seymour (Dem.) was nominated for Governor; Mr. Cornell (Whig) for Lieutenant Governor; Mr. Mather (Dem.) for Canal Commissioner; and Mr. Smith (Whig) for Clerk of the Court of Appeals. This movement in New York City in favor of these candidates, caused a reaction in favor of the others in the country districts of the state. The election occurred on the 5th of November, and resulted as follows:

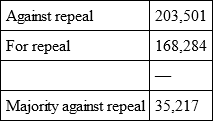

From this it will be seen that Mr. Hunt was elected Governor, and all the rest of the Democratic ticket was successful. Thirty-four members of Congress were also elected, there being 17 of each political party. The Legislature is decidedly Whig. In the Senate, which holds over from last year, there is a Whig majority of 2; and of the newly elected members of Assembly, 81 are Whigs, and 47 Democrats. This result derives special importance from the fact that a U.S. Senator is to be chosen to succeed Hon. D.S. Dickinson, whose term expires on the 4th of March, 1851. The vote on the Repeal of the Free School Law was as follows:

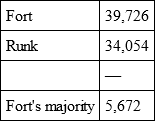

In New Jersey a state election also occurred on the 5th of November. The candidates for Governor were Dr. Fort, Democrat, and Hon. John Runk, Whig. The result of the canvass was as follows:

Five members of Congress were also elected, 4 of whom were Democrats, and 1 Whig.

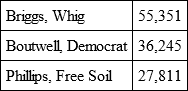

In Ohio the election occurred in October, with the following result:

Twenty-one members of Congress were elected, of whom 8 were Whigs, and 13 Democrats.

In Massachusetts the election took place on the 12th of November, with the following result for Governor – there being, of course, no election, as a majority of all the votes cast is requisite to a choice:

Of 9 Congressmen, 3 Whigs are chosen, and in 6 districts no choice was effected. Hon. Horace Mann, the Free Soil candidate, succeeded against both the opposing candidates. To the State Senate 13 Whigs and 27 of the Opposition were chosen; and to the House of Representatives 169 Whigs, 179 Opposition, and in 79 districts there was no choice. The vacancies were to be filled by an election on the 25th of November. A U.S. Senator from this State is also to be chosen, to succeed Hon. R.C. Winthrop, who was appointed by the Governor to supply the vacancy caused by Mr. Webster's resignation.

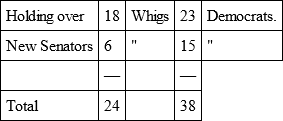

No more elections for Members of Congress will be held in any of the States (except to fill vacancies) until after March 4th, 1851. The terms of 21 Senators expire on that day – of whom 8 are Whigs, and 13 Democrats. Judging from the State elections already held there will be 6 Whigs and 15 Democrats chosen to fill their places. The U.S. Senate will then stand thus:

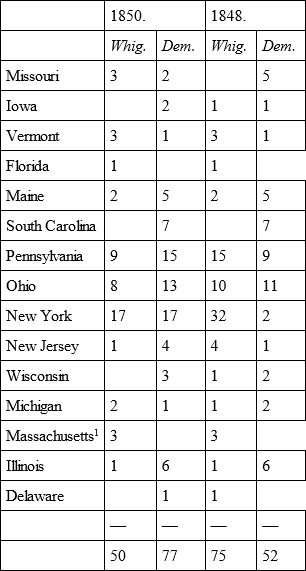

The House of Representatives comprises 233 members, of whom 127 have already been chosen, politically divided as follows – compared with the delegations from each State in the present Congress:

1Six vacancies.

Should the remaining 16 States be represented in the next Congress politically as at present, the Democratic majority would be about 30. In reference to the contingency of the next presidential election devolving upon the House, for lack of a choice by the people, 9 of the above States would go Democratic, five of them Whig, and one (the State of New York), would have no vote, its delegation being equally divided. The delegations of the same States in the present Congress are as follows, viz., 7 Whig, 7 Democratic, and one (Iowa) equally divided.

While such have been the results of the elections in the Northern States, and such the tone of public feeling there, a still warmer canvass has been going on throughout the South. We can only indicate the most prominent features of this excitement, as shown in the different Southern States.

In Georgia a State Convention of delegates is to assemble, by call of the Executive, under an act of the Legislature, at Milledgeville, on the 10th of December: and delegates are to be elected. The line of division is resistance, or submission, to the Federal Government. A very large public meeting was held at Macon, at which resolutions were adopted, declaring that, if the North would adhere to the terms of the late Compromise – if they would insure a faithful execution of the Fugitive Slave Bill, and put down all future agitation of the slavery question – then the people of the South will continue to live in the bonds of brotherhood, and unite in all proper legislative action for the preservation and perpetuity of our glorious Union. Hon. Howell Cobb, Speaker of the House of Representatives, made a speech in support of these resolutions. Hon. A.H. Stephens, R. Toombs, Senator Berrien, and other distinguished gentlemen of both parties, have made efforts in the same direction, and public meetings have been held in several counties, at which similar sentiments were proclaimed. The general feeling in Georgia seems to be in favor of acquiescence in the recent legislation of Congress, provided the North will also acquiesce, and faithfully carry its acts into execution.

In South Carolina, the whole current of public feeling seems to be in favor of secession. At a meeting held at Greenville, on the 4th of November, Col. Memminger made a speech, in which he expressed himself in favor of a Confederation of the Southern States, and if that could not be accomplished, then for South Carolina to secede from the Union, stand upon and defend her rights, and leave the issue in the hands of Him who ruleth the destinies of nations. He was answered by General Waddy Thompson, who depicted forcibly and eloquently the ruinous results of such a course as that advised, and repelled the charges of injustice urged against the Northern States. The meeting, however, adopted resolutions, almost unanimously, embodying the sentiments of Col. Memminger. And the tone of the press throughout the state is of the same character.

In Alabama public opinion is divided. A portion of the people are in favor of resistance, and called upon Gov. Collier to convene a State Convention, to take the matter into consideration. The Governor has issued an address upon the subject, in which he declines to do so, at present, until the course of other Southern States shall have been indicated. He says that while all profess to entertain the purpose to resist aggression by the Federal Legislature on the great southern institution, public opinion is certainly not agreed as to the time or occasion when resistance should be interposed, or as to the mode or measure of it. He apprehends renewed efforts for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, and pertinacious exertions for the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law; that California will be divided into several States, and that the North will thus acquire power enough so to amend the Federal Constitution as to take away the right of representation for the slaves – a result which he, of course, regards as fatal to the South. He believes that any State has a right to secede from the Union, at pleasure, but thinks that a large majority of the people of Alabama, are strongly disinclined to withdraw from the confederation, until other measures have been unsuccessfully tried to resist further aggression. Under these circumstances, he recommends the people of the State so to develop their resources, establish manufactures, schools, shipping houses, &c., as to become really independent of the North. This is the policy which, in his judgment, will prove most effectual in securing the rights, and protecting the interests of the South. Hon. Mr. Hilliard has written a letter to the citizens of Mount Meigs, declaring that, though opposed to the admission of California, he sees nothing in the measures of the last session which would justify the people of the Southern States in resisting them, or furnish any ground for revolution. A very large mass meeting of the citizens of Montgomery county, held on the 20th of October, adopted resolutions, first reciting that a systematic and formidable organization is in progress in some of the Southern States, having for its object some form of violent resistance to the Compromise measures passed by Congress at its last session; and that if this resistance is carried out according to the plans of a portion of the citizens of the Southern States, it must, inevitably, lead to a dissolution of the Union; and that the Montgomery meeting, though they do not approve of them all, do not consider these measures as furnishing any sufficient and just cause for resistance; and then declaring, 1. That they will rally under the flag of the Union. 2. That they will support no man for any office, who is in favor of disunion, or secession, on account of any existing law or act of Congress. 3. That they acquiesce in the recent action of Congress. And, 4. That if the Compromise should be disturbed, they will unite with the South in such measures of resistance as the emergency may demand.

In Mississippi the contest is no less animated. It was brought on by the issuing of a proclamation by Gov. Quitman, calling a State Convention, for the purpose of taking measures of redress. A private letter, written by Gov. Quitman, has also been published, in which he avows himself in favor of secession. On the last Saturday in October, a mass meeting was held at Raymond, at which Col. Jefferson Davis was present, and made a speech. He was strongly in favor of resistance, but was not clear that it should be by force. He thought it possible to maintain the rights of the South in the Union. He was willing, however, to leave the mode of resistance entirely to the people, while he should follow their dictates implicitly. Mr. Anderson replied to him, and insisted that the Federal Government had committed no unconstitutional aggression upon the rights of the South, and that they ought, therefore, to acquiesce in the recent legislation of Congress. Senator Foote is actively engaged in canvassing the state, urging the same views. He meets very violent opposition in various sections.

In Louisiana indications of public sentiment are to be found in the position of the two United States Senators. Mr. Downs, in his public addresses, takes the ground that the South might as well secede because Illinois and Indiana are free States as because California is. He admits that California is a large State, but he says she is not half so large as Texas, a slave State, brought into the Union five years ago. Mr. Soulé, the other Senator, having expressed no opinion upon the subject, was addressed in a friendly note of inquiry first by Hon. C.N. Stanton, asking whether he was in favor of a dissolution of the Union, of the establishment of a Southern Confederacy, or of the secession of Louisiana, because of the late action of Congress. Mr. Soulé, in his reply, complains bitterly of the "vile abuse" heaped upon him, charges his correspondent with seeking his political destruction, and refers him to his speeches in the Senate for his sentiments upon these questions. A large number of the members of his own party then addressed to Mr. Soulé the same inquiries, saying that they did it from no feeling of unkindness, but merely to have a fair and proper comprehension of his opinions upon a most important public question. Mr. S., under date of Oct. 30, replies, refusing to answer their inquiries, and saying that their only object was to divide and distract the Democratic party. Senator Downs, in reply to the same questions, has given a full and explicit answer in the negative: he is not in favor of disunion or secession.

A letter written during the last session of Congress, dated January 7, 1850, from the Members of Congress from Louisiana, to the Governor of that State, has recently been published. It calls his attention to the constant agitation of the subject of slavery at the North, and to the fact that the legislature of every Northern State had passed resolutions deemed aggressive by the South, and urging the Governor to recommend the Legislature of Louisiana to join the other Southern States in resisting this action. The opinion is expressed that "decisive action on the part of the Southern States at the present crisis, is not only not dangerous to the Union, but that it is the best, many think, the only way of saving it."

Among the political events of the month is the publication of a correspondence between Hon. Isaac Hill, long a leader of the Democratic party in New Hampshire, and Mr. Webster, in regard to the efforts of the latter to preserve the peace and harmony of the Union by allaying agitation on the subject of slavery. Mr. Hill, under date of April 17, wrote to Mr. Webster expressing his growing alarm at the progress of ill-feeling between the different sections of the country, and his conviction that "all that is of value in the sound discrimination and good sense of the American people will declare in favor of Mr. Webster's great speech in the Senate upon that subject. Its author," he adds, "may stand upon that alone, and he will best stand by disregarding any and every imputation of alleged inconsistency and discrepancy of opinion and practice, in a public career of nearly half a century." Mr. Webster, in acknowledging the letter, speaks of it as "an extraordinary and gratifying incident in his life," coming as it did from one who had long "belonged to an opposite political party, espoused opposite measures, and supported for high office men of very different political opinions." They had not differed, however, in their devotion to the Union; and now, that its harmony is threatened, it was gratifying to see that both concurred in the measures necessary for its preservation. His effort, he says, had been and would be to cause the billows of useless and dangerous controversy to sleep and be still. He was ready to meet all the consequences which are likely to follow the attempt to moderate public feeling in highly excited times, and he cheerfully left the speech to which Mr. Hill had alluded, "with the principles and sentiments which it avows, to the judgment of posterity."

A public dinner was given to the Hon. John M. Clayton on the 16th of November, by the Whigs of Delaware, at Wilmington, at which Mr. C. made a long and eloquent speech in vindication of the policy pursued by the late President Taylor and his Administration. He paid a very high tribute to the personal character, moral firmness, patriotism, and sagacity of the late President, and vindicated his course from the objections which have been urged against it. He expressed full confidence in the perpetuity of the Union, and ridiculed the apprehensions that have been so widely entertained of its dissolution. A large number of guests were present, and letters were read from many distinguished gentlemen who had been invited but were unable to attend. Preferences were expressed at the meeting for Gen. Scott as a candidate for the Presidency in 1852.

Colonel Richard M. Johnson, Vice President of the United States for four years from 1836, died at Frankfort, Ky., on the 19th of November, aged 70. He has been a member of Congress, and Senator of the United States from Kentucky, and acquired distinction under General Harrison in the Indian war of 1812. At the time of his death he was a member of the Kentucky Legislature.

GREAT BRITAIN

The event of the month which has excited most interest, has been the establishment by the Pope of Roman Catholic jurisdiction in England. The Pope has issued an Apostolic Letter, dated September 24th, which begins by reciting the steps taken hitherto for the promotion of the Catholic faith in England. Having before his eyes the efforts made by his predecessors, and desirous of imitating their zeal, and carrying forward to completion the work which they commenced, and considering that every day the obstacles are falling off which stood in the way of the extension of the Catholic religion, Pius IX. believes that the time has come when the form of government should be resumed in England such as it exists in other nations. He thinks it no longer necessary that England should be governed by Vicars Apostolic, but that she should be furnished with the ordinary episcopal form of government. Being confirmed in these thoughts by the desires expressed by the Vicars Apostolic, the clergy and laity, and the great body of English Catholics, and, also, by the advice of the Cardinals forming the Congregation for Propagating the Faith, the Pope decrees the re-establishment in England of a hierarchy of bishops, deriving their titles from their own Sees, which he constitutes in the various Apostolic districts. He then proceeds to erect England into one archiepiscopal province of the Romish church, and divides that province into thirteen bishoprics.

The promulgation of this letter created throughout England a feeling of angry surprise, and nearly the whole of London has teemed with the most emphatic and earnest condemnation of the measure. In order somewhat to mitigate the alarm of startled Protestantism, Dr. Ullathorne, an eminent Catholic divine, has published a letter to show that the act is solely between the Pope and his spiritual subjects, who have been recognized as such by the English Emancipation Act, and that it does not in the slightest degree interfere with the laws of England, in all temporal matters. He shows that the jurisdiction which the Pope has asserted in England, is nothing more than has been exercised by every communion in the land, and that nothing can be more unfair than to confound this measure, which is really one of liberality to the Catholics of England, with ideas of aggression on the English government and people. In 1688, he says, England was divided into four vicariates. In 1840, the four were again divided into eight; and, in 1850, they are again divided and changed into thirteen. This has been done in consequence of efforts begun by the Catholics of England, in 1846, and continued until the present time. By changing the Vicars Apostolic into Bishops in ordinary, the Pope has given up the exercise of a portion of his power, and transferred it to the bishops. This letter, with other papers of a similar tenor, has somewhat modified the feeling of indignation with which the Pope's proceeding was at first received, and attention has been turned to the only fact of real importance connected with the matter, namely, the rapid and steady increase of the Roman Catholics, by conversions from the English Established Church. The Daily News, in a paper written with marked ability, charges this increase upon the secret Catholicism of many of the younger clergy, encouraged by ecclesiastical superiors, upon the negligent administration of other clergymen, and upon the exclusive character of the Universities. Very urgent demands are made by the press, and by the clergy of the Established Church, for the interference of the Government against the Pope's invasion of the rights of England; but no indications have yet been given of any intention on the part of ministers to take any action upon the subject.

A good deal of attention has been attracted to a speech made by Lord Stanley, the leader of the Protectionist party in England, at a public dinner, Oct. 4th, in which he urged the necessity, on the part of the agricultural interests of the kingdom, of adapting themselves to the free-trade policy, instead of laboring in vain for its repeal. The speech has been very widely regarded as an abandonment of the protective policy by its leading champion, and it is, of course, considered as a matter of marked importance with reference to the future policy of Great Britain upon this subject. The Marquis of Granby, on the other hand, at the annual meeting of the Waltham Agricultural Society, held on the 19th of October, again urged the necessity of returning to the old system of protection, and exhorted reliance on a future Parliament for its accomplishment. The subject of agriculture is attracting an unusual degree of attention, and the various issues connected with it, form a standard topic of discussion in the leading journals.

The Tenant Right question continues to be agitated with great earnestness and ability in Ireland. A deputation from the Ulster Tenant Right Provincial Committee waited on the Earl of Clarendon during his visit to Belfast to present an address. The earl declined to receive them, but wrote a letter, dated Sept. 18, in reply to one inclosing a copy of the address. He expressed great satisfaction at the prevalence of order and at the evidence of agricultural prosperity, and assured them of the wish of the government to settle the rights of tenants on a just and satisfactory basis. A great Tenant Right meeting was held at Meath, October 10th, at which some 15,000 persons are said to have been present.