полная версия

полная версияBohemia under Hapsburg Misrule

The literary men and the “vlastenci” (patriots) were looked upon by many people with good-natured tolerance. Enemies of the cause regarded them with ill-concealed suspicion, not infrequently with contempt, while the government, distrusting everything that was new, suspected them of dangerous intrigues against the safety of the state. It must be borne in mind that there was no political freedom in Austria then; matters of public concern were not allowed to be discussed, much less criticised, except among intimates.

The work of resuscitating a dying race was a gigantic task, and but for the perseverance of the first apostles, the most promising branch of the Slavic linden tree would have withered. It was necessary to build theatres, to found learned societies, to establish museums and libraries, to collect and edit rare books and manuscripts scattered in foreign countries, whither they had been carried by soldiers during the Thirty Years’ War. The Austrian Government, instead of assisting in this work which had for its object the uplifting of a down-trodden people from ignorance, superstition, and bigotry, hindered it at every step. As an example of self-sacrificing patriotism, the case of a law student by the name of Řehoř should be mentioned. This man took a vow that he would distribute as many Bohemian books as were said to have been burnt by the Jesuit Koniáš during the anti-reformation, that is, 60,000 volumes. Řehoř died some time in the late fifties of the nineteenth century, and he is said to have accomplished the greater part of his self-imposed task. When Jungmann, one of the greatest of the revivalists, died in 1847, the patriots had an opportunity to review their growing ranks and they were astonished how the national movement had spread. “When we were returning home from the funeral,” noted J. V. Frič in his memoirs, “I walked arm in arm with my father; we both felt proud like victors who were marching to further decisive battles. When father in the evening sat down for a chat with the family, he exclaimed, breathing freely as if a stone had rolled off his chest, ‘Children, I think we shall win; there are too many of us; they can no longer trample us down.’”

POLITICAL AWAKENINGUp to 1848 Austrian subjects enjoyed certain liberties: they could smoke, drink, and play cards without interference from the police. One enjoyment, however, was denied to them – they were not permitted to think. Prince Metternich, the personification of absolutist Austria of those days, observed with alarm how the structure that he had been propping for years was beginning to settle in its foundations, and how ominous cracks appeared in it here and there.

Revolution was in the air. Switzerland, Germany, and Italy were being engulfed by it. “The world is ill,” Metternich complained in a letter to Count Apponyi. “Each day we can observe how the moral infection is spreading, and if you find me unyielding, it is because I am of a nature that will not give in before opposition.”

The news of the fall of Louis Philippe in France reached Prague February 29, 1848. Next day, notwithstanding the strictest censorship, the city was aflame with revolutionary talk. The liberals in neighboring Germany had summoned delegates to meet at Frankfort, March 5th. Italy seethed with political excitement. Kossuth, in Hungary, demanded that a constitution be granted to the people in Austria. Overnight Metternich’s elaborate system of government, maintained by the police and the military, was tumbling down like a house of cards. In Prague, as in other large centres, everybody clamored for a constitution, though the masses, educated as they were to regard the government as something above and apart from them, hardly comprehended what the word “constitution” meant.

In the midst of the turmoil the sickly Emperor Ferdinand V. (1835-1848) abdicated in favor of his nephew, Francis Josef, then a youth of eighteen. The latter had been on the throne but a few weeks, when his advisers, Schwarzenberg, Windischgrätz, Stadion, and others, decided to do away with the constitution of the revolutionists and to substitute it with an octroy constitution, the reason assigned being “the incapacity of parliament.” The choice fell on this particular young man because Prince Schwarzenberg recommended as ruler “one whom he would not have to be ashamed to show to the troops.” Though not relevant, it is interesting to recall how the present emperor acquired his cognomen. “What shall it be, gentlemen,” asked Schwarzenberg in the ministerial council – “Francis Josef, or simply Francis?” A sub-secretary of state thought that plain Francis would sound very well indeed, but the fear having been expressed that the name Francis might remind the Austrian nations too much of the ghost of Metternich, Francis Josef, instead of plain Francis, was chosen for the youthful monarch.

To Windischgrätz constitutions, ministries accountable to the people, and parliaments were abominations. He made no secret of the fact that he was opposed to the rule of lawyers; those alone who carried bayonets and muskets were entitled to be called patriots and saviors of the fatherland.

Under the Premiership of Alexander Bach (1853-1859) the monarchy relapsed to the methods of police rule that obtained prior to 1848. The reactionaries who surrounded the throne encouraged the youthful monarch to rule like an autocrat.

Minister Bach, by the way a highly gifted man, who had in his early days trifled with radicalism, believed that an alliance between the church and the state would strengthen both and that against the unity of the altar and the throne the radicals would be powerless. “The Austrian Monarchy,” he confided to a noted clerical, “considering its peculiar structure, has only two firm bases on which it can rest in safety and unity, – the dynasty and the church.” Accordingly he brought about, in 1855, the adoption of the famous concordat, a convention between the pope and the monarchy, a pact that increased immensely the legal power of the papacy in Austria. The concordat was abolished in 1868 because of the bitter opposition of the liberals. Bohemia, the land of Hus and Havlíček, fought the concordat openly and fearlessly, suspecting in it a hidden menace to its freedom of conscience and to national aspirations.

The uncompromising opposition of the Bohemians to Bach and to his policies visited upon them the wrath of Vienna. Under Bach they were probably subjected to oppression more ruthless and cruel than any they had experienced since the time of Ferdinand II.

Patriots, some of them mere youths, were thrown in prison on the flimsiest accusation of police spies. It was not safe to converse in Bohemian in the streets of Prague. Spies were at the heels of every Bohemian prominent in public life. Police agents tried to connect Francis L. Rieger with a treasonable plot to disrupt the monarchy and he had to flee the state to save himself from prison. Spies followed Palacký even to the sick-bed of his wife. The military authorities at Prague suspended the publication of Havlíček’s famous newspaper, “Národní Noviny,” on the ground that its editor indulged in “immoderate language.” Finding Prague closed to his paper, Havlíček made an attempt to publish it in Vienna. “I am determined not to issue licenses to any newspaper in Vienna; we have enough newspapers as it is,” replied General Welden to Havlíček’s application for the license. “But there is no such newspaper in Vienna as I should like to publish,” pleaded Havlíček. “My paper is intended to be an organ for Slavic matters and it is to be printed in Bohemian.” Welden retorted angrily: “Wir sind hier Deutsche” (Here in Vienna we are Germans), and the General’s decision was irrevocable. Undaunted, Havlíček made other attempts to procure a newspaper license, and at last he obtained a promise that he might be allowed to publish a paper in Kutná Hora, a provincial town not far from Prague. In time even this paper was suppressed by the police and its editor arrested and interned in the province of Tyrol by Bach’s order. It should, perhaps, be said that Havlíček was the one journalist whom neither threats nor offers of bribery could influence. There, separated from his wife and child, Havlíček gave way to brooding which brought on a fatal brain disease. From Tyrol he was permitted to return home, broken in health and spirit. To the last Havlíček remained steadfast to the cause he had championed – the liberation from bondage of his nation. Havlíček’s colors were red and white (Bohemian national colors), and neither threats nor favors could swerve him from his chosen path:11 “They banished you from the fatherland,” wrote Pinkas to Havlíček, “but they transformed the fatherland itself into a fortress and a jail. We live here the most unhappy lives conceivable. Not a ray of light enters our intellectual prison to brighten it.”

The mere acquaintanceship with Palacký was enough to expose one to the chicanery of the police. Strobach, at one time Mayor of Prague and a former speaker of the short-lived parliament, was deposed as judge because, when presiding at a trial, he failed to hold a drunkard on a charge of lèse majesté. Count Thun would not allow Rieger to lecture at the university for the reason, as he stated, “that students would see in him a political agitator, not a professor.”

A demand was made on Palacký by the censor to strike out of his “History of the Bohemian Nation” the chapters relating to Hus and the Hussite Wars. Even Prince Metternich, whose bureaucratic leanings were above suspicion, considered the demand, which was equivalent to an order, unreasonable. After a great deal of haggling as to what was permissible and what should be deleted, a compromise was effected between the historian and the censor. However, Palacký’s biographers all agreed that the terms of the compromise were not satisfactory to him. He is said to have expressed a hope that future historians, living in freer times than he, should tell the whole truth about the importance and meaning of the Hussite movement, which he was not allowed to do. The chapters relating to the Hussite times he wrote both in Bohemian and German. But because German critics had impugned his impartiality, he determined, as a protest, to continue with Bohemian as the original and German as a translation. When he announced his decision to the Land Committee, a protest was raised and he was warned not to publish the Bohemian text before the German; nor to do anything from which it might appear that the German text was not the original.

The famous physician, Hamerník, a pupil of the noted Škoda and Rokytanský, was removed from the university because the government suspected his political and religious views.

The publication of every Bohemian newspaper in the land was suspended, except for two or three scientific and literary magazines, and the police would have liked to destroy even those, if decent pretext could have been found for their doing so.

At one time the authorities were planning to dissolve the society of the Bohemian Museum and the Royal Society of Sciences. The discussions of these learned bodies did not seem patriotic enough from the Austrian point of view. The Matice Česká – a society for the publication of standard literature – was threatened in its existence, and only the influence of some of its prominent members saved it from the fury of the almighty police.

Pogodin, the Russian scholar, had recommended the Matice to publish the works of Hus. “God prevent,” answered Šafařík to Pogodin’s letter (1857). “Who would think of publishing books on Hus in Austria? – yes, if they were against Hus – that would be simple.”

Before Krejčí’s work on geology could be published, every page, nay every line, was carefully scanned, and when that was done the manuscript was ordered to be submitted for approval to a learned priest, to make sure that it contained nothing contrary to the teaching of the church. Palacký, who was always dreaming of his pet scheme of the publication of a Bohemian encyclopedia, was told that “under the existing press laws it would be unwise to urge the matter.”

In honor of the emperor’s marriage (1854) the government showed clemency to certain political persons; yet, in general, conditions remained unchanged. Patriots who had been expelled from Prague could return, but city or country, their movements were watched by the police. Sladkovský, a famous journalist whose publications had been ruined by censorship, applied for a license to start a coal yard with which to support his family. The application was promptly disallowed. Young Frič, a literary rebel, planned to issue a volume of poetry with the collaboration of the younger set of writers. This warning was received from Vienna: “Let Frič beware; if he does not desist in his dangerous course, he may again find himself interned in a fortress.” The police directors and press censors suspected the loyalty of everyone who ventured to write in Bohemian. “I fail to comprehend,” remonstrated Police Director Weber with Frič, “why you persist in this ridiculous nonsense; in about six years there will be nothing left of your Bohemian literature, anyway.”

On another occasion Weber gave Frič to understand that Bohemia was a German territory, and that if he wished to live in it he must obey German laws. Yet Frič was incorrigible. For his intractability and because he would not share Weber’s view that his nation was doomed to extinction, he was banished to the hills of Transylvania.

On the battlefields at Magenta and Solferino in Italy in 1859, the absolutist rule of Bach, which derived its chief support from the bureaucracy, the military, and the clerical party, came to an abrupt end. The progressive element clamored for reforms. Bach was dismissed from office and his successor (Goluchowski) announced that in the future the state budget would be subject to the scrutiny of the people and that provincial diets would be invited to legislate on their needs. The last part of the program the federalists interpreted to mean that the principle of local self-government had at last been recognized.

In the Bohemian Diet a prominent member, encouraged by the program of the new premier, moved, amid genuine enthusiasm of the federalists, that a deputation of the diet be appointed to go to Vienna and urge the emperor to have himself crowned king in Prague. When, subsequently, a deputation of the diet secured an audience from the ruler, he declared (1861): “I will be crowned in Prague as King of Bohemia, and I am convinced that this ceremony will cement anew the indissoluble tie of confidence and loyalty between My throne and My Bohemian Kingdom.”

Bohemians were elated. At last their ideal of autonomous Bohemia seemed at the point of realization.

Here a few words should be said concerning the constitution under which Austrians were to begin a new parliamentary life. The much-heralded and impatiently awaited document was drafted by Minister Schmerling, a staunch centralist, and because it was promulgated in February (1861) it was called the “Constitution of February.” As soon as its text had been made public, the Slavs instantly recognized that the statesmen in Vienna had not profited in the slightest from the lessons of 1848. Minister Schmerling, was, like all Germans, obsessed with the notion that German hegemony was indispensable to the safety and greatness of the state. Accordingly he subordinated every other idea and interest to that one obsession. A most ingenious electoral system was evolved whereby Germans, though in minority, were able to control, not only the central parliament, but the provincial diets as well. The scheme was to favor the cities, wealthy individual taxpayers, and chambers of commerce (which groups then were German in sentiment) to the disadvantage of the agricultural districts inhabited by the Slavs. How the electoral law worked in Bohemia one can perceive from the fact that in 1873 2,500,000 Bohemians were able to elect only 34 deputies, while 1,500,000 Germans contrived to return 56 deputies. The powers of the provincial diets were reduced to a minimum, the controlling idea, of course, being to keep centred in Vienna the entire power of the state. By reason of this juggling the Bohemian element found itself in minority in its own Land Diet.

Although distrustful because of the partisanship evinced in the constitution, the Bohemians nevertheless entered parliament, but they did so upon the express understanding that their participation therein should not be in any manner prejudicial to the historical rights of their kingdom.

Generally speaking, the Austrian nations, from the very first day their representatives were permitted to enter the legislative halls, divided themselves into two political parties, federalists and centralists. The federalists favored granting self-government to the various races; the centralists, who were backed by the German masses, opposed this. Austria, according to the latter, was lost to the German cause the moment the agitation “Away from Vienna” had gained the upper hand. For reasons of self-protection the Slavs, led by the Bohemians, inclined toward federalism, as more likely to satisfy their national aspirations. Instead of a Teutonic Austria, the Slavs desired a United States of Austria that should be just and impartial to all.

For months the Bohemians waited, but to their surprise and dismay the government took no steps to make effective the emperor’s promise. On the contrary, the increasing persecution of their press, the brutal partiality of the speaker of parliament, the hostile attitude of the executive organs of the government were signs, the significance of which could not be doubted. The discouraging truth dawned on them at last that the emperor had no intention of keeping his word and of giving home rule to his Bohemian subjects.

Deceived by their sovereign and realizing that neither reason nor justice would influence Vienna, they decided, in 1863, as a means of protest and to show their deep resentment, to leave the parliament in a body. On June 17th of that year they issued a statement in which the grievances of the nation were set forth at length. For sixteen years after that no Bohemian legislator appeared in the Austrian Parliament. And while this may not have been a sagacious course – indeed, subsequent events have shown that the “policy of abstinence,” as the parliamentary boycott came to be known, almost irreparably prejudiced their position – yet, as a protest of an outraged nation, it was magnificent.

DUALISM – A BLUNDER AND A CRIMEUp to 1867 the Hapsburg Monarchy was, outwardly at least, a Teutonic state. But in 1866, having been decisively beaten by Prussia at Sadova, it found itself facing a new destiny. Expelled from the Germanic Bund of which it had been a leading member, the championship wrested from it by victorious Hohenzollerns, rent by internal discord, its statesmen concurred in the opinion that reconstruction of some kind was inevitable. But what course of action should be pursued? Should the government again have recourse to the shop-worn policy of rigid centralization and Germanization which had been tried by Austrian Premiers time and time again and invariably found wanting?

That Hungary should be given back her autonomy was conceded beforehand. Weakened by war, its military prestige shattered, its finances at a low ebb, the government was in no condition to resist the Magyars, who had assumed a threatening attitude. But what about the Bohemians, who also clamored for recognition? Bohemia, Hungary, and Austria, it will be remembered, had formed a union in 1526-1527 on terms of equality. And then how should the larger Slavic questions be settled? Numerically the Slavs were the strongest element in the monarchy. If allowed to elect representatives to one central parliament, these discontented Bohemians, Poles, Slovaks, and Croatians might one day, uniting politically, control the country. Tacitly Vienna and Budapest agreed that, whatever the terms of the settlement with Hungary, the disaster of Slavic majority must be averted.

“The Slavs must be pressed to the wall” (Man wird die Slaven an die Wand drücken), declared a statesman who participated actively in the plan of reconstruction. “You,” addressing the Magyars, “will take care of your hosts [meaning the Slavs] and we shall take care of ours.” In the parliament the cause of the Slavic federalists was lost beforehand; a German-made constitution and German-made electoral law rendered futile every opposition. Besides, the government would brook no interference with its plan of reconstruction as outlined by Count Beust.12 This plan contemplated a dual government, one in Vienna, the other in Budapest, and three parliaments, one to sit in Vienna for the Austrian half, one to meet in Budapest for the Hungarian half, and a third one to be called the “Delegations” and to convene alternately at both capitals to deliberate on matters common to the empire as a whole, such as foreign relations, the army, navy, finances, and so forth. In other words, Beust’s plan provided for two seats of centralization instead of one. From a German state that it had been before 1867 Austria became a German-Magyar state – an organization without precedent or analogy. The several kingdoms, crown-lands, etc., were divided under Beust’s plan; and, upon the consummation of the deal, were allotted to the contracting parties to the dualism as follows: Austria received Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Bukovina, Dalmatia, Galicia, Carinthia, Carniola, Trieste and vicinity, Goritz and Gradiska, Istria, Lower Austria, Upper Austria, Salzburg, Styria, Tyrol, Voralberg. Hungary secured as her part of the bargain Hungary Proper, Transylvania, Fiume, Croatia, Slavonia, and the Military Frontier.

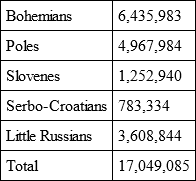

Figures, better than anything else, will explain why the Slavs were opposed to dualism and presently became its irreconcilable enemies. Under the Austrian roof Beust put these Slavic groups (quoting from the census of 1910):

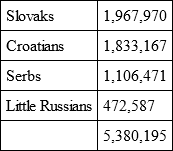

Under the Magyar domination fell the following Slavs:

Beust’s scheme was audaciously clever. By dividing the monarchy in two he divided the Slavs; and, separated and isolated, they were made easier victims of Magyarization in Hungary and of Germanization in Austria. A crying injustice of this shameful bargain was that the “high contracting parties” tore apart peoples of the same race, setting up a political barrier where nature intended that none should exist. Austria, for instance, had been awarded Dalmatia, the population of which is almost wholly Croatian; yet Slavonia and Croatia, which is also Croatian to the core (or Serbo-Croatian), went to Hungary. Bohemians of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia were lodged under the Austrian roof; the Slovaks, on the other side, who are almost one with the Bohemian race, were put under the guardianship of Hungary. Nations and races were moved on the Austrian chess-board like so many pawns – exactly the same way as at the Vienna Congress in 1814 and at the Berlin Conference in 1878.

“No people in the monarchy were more unjustly prejudiced by dualism than the Bohemians,” is the opinion of Denis. “Every article of the Settlement affected their interests most adversely. Their kinsmen, the Croatians and Serbs, and particularly the Slovaks – the latter always confidently looked upon as a reserve force of the nation – were handed out to merciless and unfeeling masters. The crown of St. Václav (St. Václav is honored as patron saint of Bohemia) was reduced by Vienna to a position of semi-vassalage and given equal rank with a medley of outlying and insignificant provinces. Dualism condemned the Slavs to be the unwilling tools of a policy to which they had been opposed. Bohemia, the richest and most productive land in the empire, was made to bear the heaviest quota of the burden with which statesmen had saddled the Austrian half of the monarchy.” Condemning dualism, Dr. Edward Grégr, in a famous speech delivered in parliament, declared “that it would be wisest to tear down to its foundations the ramshackle building that made every tenant dissatisfied, that lacked light and air, that neither expense nor labor could make habitable, and to build upon the ruins an edifice answering the manifold needs of its inhabitants. In the judgment of Dr. Menger” (a German deputy), thundered Grégr, “this would be a treason and I confess that it would be a treason. Yet, is not dualism a treason on the rights and liberties of the peoples of this state and particularly on the rights and liberties of our Bohemian nation?”