полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 62, Number 361, November, 1845.

These may be taken as two great instances of the danger of foreign speculation. The capital of the mining companies was squandered with no other effect than that of providing employment, for a certain number of years, to the lowest of the Mexican peasantry; whereas the same amount, applied to a similar purpose in this country, would not only have produced a handsome return to the invester, but would have afforded work and wages to a considerable portion of the community. There is a reciprocity between labour and capital which never ought to be forgotten. Labour is the parent of all capital, and capital, therefore, should be used for the fostering and assistance of the power by which it is produced. Here, however, it was removed, and became, to all intents and purposes, as useless and irrecoverable as the bullion on board of a vessel which has foundered at sea. This, therefore, may be regarded as so much lost capital; but what shall we say to the other instance? Simply this – that whoever has lost by the failure of American banks, by repudiation, or by stoppages of dividends, need not claim one single iota of our compassion. With British money has the acute Columbian united state to state by more enduring ties than can be framed within the walls of Congress – with it, he has overcome the gigantic difficulties of nature – formed a level for the western waters where none existed before – pierced the interminable forests with his railroads, and made such a rapid stride in civilization as the world has never yet witnessed. What of all this could he have done on his own resources? Something, we must allow – because his spirit of enterprise is great, even to recklessness, and a young and forming country can afford to run risks which are impossible for an older state – but a very small part, unquestionably, without the use of British capital. We cannot, and we will not, believe that any considerable portion of these loans will be ultimately lost to this country. Great allowance must be made for the anger and vexation of the prospective sufferers at the first apparent breach of international faith, and it is no wonder if their lament was both loud, and long, and heavy. But we think it is but a fair construction to suppose that our Transatlantic brethren, in the very rapidity of their "slickness," have carried improvement too far, given way to a false system of credit among themselves, and so, having outrun the national constable, have found themselves compelled to suspend payment for an interval, which, in the present course of their prosperity, cannot be of long continuance. So at least we, having lent the American neither plack nor penny, do in perfect charity presume; but in the mean time he has our capital – say now some thirty millions – he has used it most thoroughly and judiciously for himself, and even supposing that we shall not ultimately suffer, what gain can we qualify thereby?

If John Doe hath an estate of some twenty thousand acres in tolerable cultivation, which, nevertheless, in order to bring it to a perfect state of production, requires the accessaries of tile-draining, planting, fencing, and the accommodation of roads, it is quite evident that his extra thousand pounds of capital will be more profitably expended on such purposes than on lending it to Richard Roe, who has double the quantity of land in a state of nature. For Richard, though with the best intentions, may not find his agricultural returns quite so speedy as he expected, may shake his head negatively at the hint of repayment of the principal, and even be rather tardy with tender of interest at the term. John, moreover, has a population on his land whom he cannot get rid of, who must be clothed and fed at his expense, whether he can find work for them or no. This latter consideration, indeed, is, in political economy, paramount – give work to your own people, and ample work if possible, before you commit in loan to your neighbour that capital which constitutes the sinews alike of peace and of war.

We believe there are few thinking persons in this country who will dispute the truth of this position. Indeed, the general results of foreign speculation have been unprofitable altogether, as is shown by the testimony of our ablest commercial writers. One of them gives the following summary: – "Large sums have, from time to time, been lent to various foreign states by English capitalists, whose money has been put to great hazard, and, in some cases, lost. On the other hand, many foreign loans have been contracted by our merchants, which have proved highly profitable, through the progressive sale of the stock in foreign countries at higher than the contract prices. It is evidently impossible to form any correct estimate of the profit or loss which has resulted to the country from these various operations; the general impression is, that hitherto the losses have much exceeded the gains." In that general impression we most cordially concur – indeed, we never heard any man whose opinion was worth having, say otherwise.

But in the absence of home speculation it is little wonder that, for the chance of unfrequent gain, men should choose, rather than leave their capital unemployed, to run the risk of the frequent loss. It does not, however, follow, as a matter of course, that home speculation shall always prove profitable either to the invester or to the nation at large. We have said already, that the proper function of capital is to foster and encourage labour; but this may be carried too far. For example, it is just twenty years ago, when, at a time of great prosperity in trade – the regular products of this country being as nearly as possible equal to the demand – a large body of capitalists, finding no other outlet for their savings, gave an unnatural stimulus to production, by buying up and storing immense quantities of our home manufactures. This they must have done upon some abstruse but utterly false calculation of augmented demand from abroad, making no allowance for change of season, foreign fluctuation, or any other of the occult causes which influence the markets of the world. The result, as is well known, was most disastrous. Trade on a sudden grew slack. The capitalists, in alarm, threw open the whole of their accumulated stock at greatly depreciated prices. There was no further demand for manufacturing labour, because the world was glutted with the supply, and hence arose strikes, panic, bankruptcy, and a period of almost unexampled hardship to the workman, and of serious and permanent loss to the master manufacturer. Speculation, therefore, in an old branch of industry, is perilous not only to the invester but to the prosperity of the branch itself. The case, however, is widely different when a new and important source of industry and income is suddenly developed in the country.

We shall look back in vain over our past history to find any parallel at all approaching to the present state and prospects of the railway system. Forty-four years have elapsed since the first public railway in Great Britain (the Wandsworth and Croydon) received the sanction of the legislature. Twenty-five years afterwards, at the close of 1826, when the Manchester and Liverpool bill was passed, the whole number of railroad acts amounted to thirty-five: in 1838 it had increased to one hundred and forty-two. The capital of these railways, with the sums which the proprietors were authorized to borrow, cannot be taken at less than Sixty Millions Sterling.

Now, it is very instructive to remark, that until the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester line in September 1830, not one single railway was constructed with a view to the conveyance of passengers. The first intention of the railway was to provide for the carriage of goods at a cheaper rate than could be effected by means of the canals, and for the accommodation of the great coal-fields and mineral districts of England. In the Liverpool and Manchester prospectus – a species of document not usually remarkable for modesty or shyness of assumption – the estimate of the number of passengers between these two great towns was taken at the rate of one half of those who availed themselves of coach conveyance. Cotton bales, manufactures, cattle, coals, and iron, were relied on as the staple sources of revenue. Had it not been for the introduction of the locomotive engine, and the vast improvements it has received, by means of which we are now whirled from place to place with almost magical rapidity, there can be no doubt that the railways would, in most instances, have proved an utter failure. The fact is singular, but it is perfectly ascertained, that the railroads have not hitherto materially interfered with the canals in the article of transmission of goods. The cost of railway construction is incomparably greater than that attendant on the cutting of canals, and therefore the land carriage can very seldom, when speed is not required, compete with the water conveyance. But for passengers, speed is all in all. The facility and shortness of transit creates travellers at a ratio of which we probably have as yet no very accurate idea. Wherever the system has had a fair trial, the number of passengers has been quadrupled – in some cases quintupled, and even more; and every month is adding to their numbers.

But 1838, though prolific in railways, was still a mere Rachel when compared with the seven Leahs that have succeeded it. The principle of trunk lines, then first recognised, has since been carried into effect throughout England, and adopted in Scotland, though here the system has not yet had full time for development. The statistics of the railways already completed, have fully and satisfactorily demonstrated the immense amount of revenue which in future will be drawn from these great national undertakings, the increase on the last year alone having amounted to upwards of a million sterling. That revenue is the interest of the new property so created; and, therefore, we are making no extravagant calculation when we estimate the increased value of these railways at twenty millions in the course of a single year. That is an enormous national gain, and quite beyond precedent. Indeed, if the following paragraph, which we have extracted from a late railway periodical, be true, our estimate is much within the mark. "The improvement in the incomes of existing railways still continues, and during the last two months has amounted to upwards of £200,000 in comparison with the corresponding two months of 1844. The lines which have reduced their fares most liberally, are the greatest gainers. At this rate of increase of income, the value of the railway property of the country is becoming greater by upwards of £2,000,000 sterling per month." It is, therefore, by no means wonderful that as much of the available capital of the country as can be withdrawn from its staple sources of income should be eagerly invested in the railways, since no other field can afford the prospect of so certain and increasing a return.

The question has been often mooted, whether government ought not in the first instance to have taken the management of the railways into its own hands. Much may be said upon one or other side, and the success of the experiment is, of course, a very different thing from the mere prospect of success. Our opinion is quite decided, that, as great public works, the government ought most certainly to have made the trunk railways or, as in France, to have leased them to companies who would undertake the construction of them for a certain term of years, at the expiry of which the works themselves would have become the property of the nation. Never was there such a prospect afforded to a statesman of relieving the country, by its own internal resources, of a great part of the national debt. Public works are not unknown or without precedent in this country; but somehow or other they are always unprofitable. At the cost of upwards of a million, government constructed the Caledonian Canal, the revenue drawn from which does not at the present moment defray its own expenses, much less return a farthing of interest on this large expenditure of capital. Now it is very difficult to see why government, if it has power to undertake a losing concern, should not likewise be entitled, for the benefit of the nation at large, to undertake even greater works, which not only assist the commerce of the nation, but might in a very short period, comparatively speaking, have almost extinguished its taxation. It is now, of course, far too late for any idea of the kind. The golden opportunity presented itself for a very short period of time, and to the hands of men far too timid to grasp it, even if they could have comprehended its advantages. Finance never was, and probably never will be, a branch of Whig education, as even Joseph Hume has been compelled a thousand times piteously and with wringing of the hands to admit – and whose arithmetic could we expect them even to know, if they admitted and knew not Joseph's? But this at least they might have done, when the progress of railroads throughout the kingdom became a matter of absolute certainty. The whole subject should have been brought under the consideration of a board, to determine what railways were most necessary throughout the kingdom, and what line would be cheapest and most advantageous to the public; and when these points had once been ascertained, no competition whatever should have been allowed. The functions of the Board of Trade were not nearly so extensive; they had no report of government engineers, and no data to go upon save the contradictory statements of the rival companies. Hence their decision, in almost every instance, was condemned by the parties interested, who, having a further tribunal in Parliament, where a thousand interests unknown to the Board of Trade could be appealed to, rushed into a protracted contest, at an expenditure which this year is understood to have exceeded all precedent. We have no means of ascertaining the expenses of such a line as the London and York, which was fought inch by inch through the Committees of both Houses with unexampled acrimony and perseverance. We know, however, that the expenses connected with the Great Western, and the London and Birmingham bills, amounted respectively to £88,710 and £72,868, exclusive altogether of the costs incurred by the different parties who opposed these lines in Parliament. It has been stated in a former number of this Magazine – and we believe it – that the parliamentary costs incurred for the Scottish private and railway bills, during the last session alone, amounted to a million and a half.

Now, though a great part of the money thus expended is immediately returned to circulation, still it is a severe tax upon the provinces, and might very easily have been avoided by the adoption of some such plan as that which we have intimated above; and we shall presently venture to offer a few practical remarks as to the course which we think is still open to the government for checking an evil which is by no means inseparable from the system.

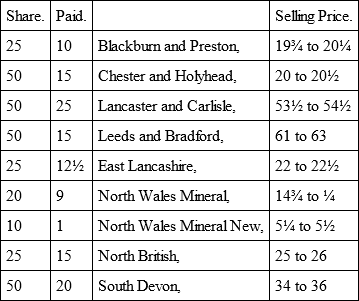

But, first, we are bound to state that, as yet, we can see no grounds for believing that the nominal amount of capital invested in the railways which have obtained the sanction of Parliament is beyond, or any thing approaching to, the surplus means of the country. Foreign speculation, except in so far as regards railroads, (and these are neither so safe nor so profitable an investment as at home,) seems for the present entirely to have ceased. The last three years of almost unequalled prosperity have accumulated in the country a prodigious deal of capital, which is this way finding an outlet; and though it may be true that the parties who originally subscribed to these undertakings may not, in the aggregate, be possessed of capital enough to carry them successfully to an end, still there has been no want of capitalists to purchase the shares at a premium – not, as we verily believe, for a mere gambling transaction, but for the purposes of solid investment. We base our calculations very much upon the steadily maintained prices of the railways which passed in 1844, and which are now making. Now, these afford no immediate return – on the contrary, a considerable amount of calls is still due upon most of them, and the earliest will probably not be opened until the expiry of ten months from the present date. It is quite obvious that, in this kind of stock, there can be no incentive to gambling, because the chances are, that any new lines which may be started in the vicinity of them shall be rivals rather than feeders; and if capital were so scarce as in some quarters it is represented to be, it is scarce possible that these lines could have remained so firmly held. Let us take the prices of the principal of these from the Liverpool share-lists as on 27th September.

These lines have, in the language of the Stock Exchange, passed out of the hands of the jobbers, and most of them are now too heavy in amount for the operations of the smaller speculators. We therefore look upon their steadiness as a high proof, not only of their ultimate value, but of the general abundance of capital.

It is hardly possible as yet to draw any such deduction from the present prices of the lines which were passed in the course of last session. Upon many of these no calls have yet been made, and consequently they are still open to every kind of fluctuation. It cannot, therefore, be said that they have settled down to their true estimated value, and, in all probability, erelong some may decline to a certain degree. Still it is very remarkable, and certainly corroborative of our view, that the amazing influx of new schemes during the last few months – which, time and circumstance considered, may be fairly denominated a craze – has as yet had no effect in lowering them; more especially when we recollect, that the amount of deposit now required upon new railways is ten per cent on the whole capital, or exactly double of the ratio of the former deposits. We give these facts to the terrorists who opine that our surplus capital is ere now exhausted, and that deep inroads have been made upon the illegitimate stores of credit; and we ask them for an explanation consistent with their timorous theory.

At the same time, we would by no means scoff at the counsel of our Ahitophels. A glance at the newspapers of last month, and their interminable advertising columns, is quite enough to convince us that the thing may be overdone. True, not one out of five – nay, perhaps, not one out of fifteen – of these swarming schemes, has the chance of obtaining the sanction of Parliament for years to come; still, it is not only a pity, but a great waste and national grievance, that so large a sum as the deposits which are paid on these railways should be withdrawn – it matters not how long – from practical use, and locked up to await the explosion of each particular bubble. We do think, therefore, that it is high time for the legislature to interfere, not for any purpose of opposing the progress of railways, but either by establishing a peremptory board of supervision, or portioning out the different localities with respect to time, on some new and compendious method.

Last session the committees, though they performed their duties with much zeal and assiduity, were hardly able to overtake the amount of business before them. It was not without much flattery and coaxing that the adroit Premier, of all men best formed for a general leader of the House of Commons, could persuade the unfortunate members that an unfaltering attendance of some six hours a-day in a sweltering and ill-ventilated room, where their ears were regaled with a constant repetition of the jargon connected with curves, gradients, and traffic-tables, was their great and primary duty to the commonwealth. Most marvellous to say, he succeeded in overcoming their stubborn will. Every morning, by times, the knight of the shire, albeit exhausted from the endurance of the over-night's debate, rose up from his neglected breakfast, and posted down to his daily cell in the Cloisters. Prometheus under the beak of the vulture could not have shown more patience than most of those unhappy gentlemen under the infliction of the lawyer's tongue; and their stoicism was the more praiseworthy, because in many instances there seemed no prospect, however remote, of the advent of a Hercules to deliver them. The only men who behaved unhandsomely on the occasion were some of the Irish members, advocates of Repeal, who, with more than national brass, grounded their declinature on the galling yoke of the Saxon, and retreated to Connemara, doubtless exulting that in this instance at least they had freed themselves from "hereditary bonds." It may be doubted, however, whether the tone of the committees was materially deteriorated by their absence. Now, we have a great regard for the members of the House of Commons collectively; and, were it on no other account save theirs, we cannot help regarding the enormous accumulation of railway bills for next session with feelings of peculiar abhorrence. Last spring every exertion of the whole combined pitchforks was required to cleanse that Augean stable: can Sir Robert Peel have the inhumanity next year to request them to buckle to a tenfold augmented task? In our humble opinion, (and we know something of the matter,) flesh and blood are unable to stand it. The private business of this country, if conducted on the ancient plan, must utterly swamp the consideration of public affairs, and the member of Parliament dwindle into a mere arbiter between hostile surveyors; whilst the ministry, delighted at the abstraction of both friend and foe, have the great game of politics unchecked and unquestioned to themselves. The surest way to gag a conscientious opponent, or to stop the mouth of an imprudent ally, is to get him placed upon some such committee as that before which the cases of the London and York, and Direct Northern lines were discussed. If, after three days' patient hearing of the witnesses and lawyers, he has one tangible idea floating in his head, he is either an Alcibiades or a Bavius – a heaven-born genius or the mere incarnation of a fool!

Let it be granted that the present system pursued by Parliament, more especially when its immediate prospects are considered, is an evil – and we believe there are few who will be bold enough to deny it – it still remains that we seek out a remedy. This is no easy task. The detection of an error is always a slight matter compared with its emendation, and we profess to have neither the aptitude nor the experience of a Solon. But as we are sanguine that wherever an evil exists a remedy also may be found, we shall venture to offer our own crude ideas, in the hope that some better workman, whose appetite for business has been a little allayed by the copious surfeit of last year, may elaborate them into shape, and emancipate one of the most deserving, as well as the worst used, classes of her Majesty's faithful lieges. And first, we would say this – Do not any longer degrade the honourable House of Commons, by forcing on its attention matters and details which ought to fall beneath the province of a lower tribunal: do not leave it in the power of any fool or knave – and there are many such actively employed at this time – who can persuade half a dozen of the same class with himself into gross delusion of the public, to occupy the time, and monopolize the nobler functions of the legislature, in the consideration of some miserable scheme, which never can be carried into effect, and which is protracted beyond endurance simply for the benefit of its promoters. We do not mean that Parliament should abandon its controlling power, or even delegate it altogether. We only wish that the initiative – the question whether any particular project is likely to tend to the public benefit, and, if so, whether this is a fit and proper time to bring it forward – should be discussed elsewhere. A recommendation of the Board of Trade, which still leaves the matter open, is plainly useless and inoperative. It has been overleaped, derided, despised, and will be so again – we scarcely dare to say unjustly; for no body of five men, however intelligent, could by possibility be expected to form an accurate judgment upon such an enormous mass of materials and conflicting statements as were laid before them. And yet, preliminary enquiry there must be. The movement is far too great, and charged with too important interests, to permit its march unchecked. Of all tyrannical bodies, a railway company is the most tyrannical. It asks to be armed with powers which the common law denies to the Sovereign herself. It seeks, without your leave, to usurp your property, and will not buy it from you at your own price. It levels your house, be it grange or cottage, lays down its rails in your gardens, cuts through your policy, and fells down unmercifully the oaks which your Norman ancestor planted in the days of William Rufus. All this you must submit to, for the public benefit is paramount to your private feelings; but it would be an intolerable grievance were you called upon to submit to this, not for the public benefit, but for the mere temporary emolument of a handful of unprincipled jobbers. Therefore there must be enquiry, even though Parliament, strangled with a multitude of projects, should delegate a portion of its powers elsewhere.