полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 62, No. 383, September 1847

However, there was no help for it, so I proceeded down stairs. The first individual I recognised in the breakfast parlour was M'Corkindale. He was engaged in singing, along with Miss Binkie, some idiotical catch about a couple of albino mice.

"Bob!" cried I. "my dear Bob, I am delighted to see you; – what on earth has brought you here?"

"A gig and a foundered mare," replied the matter-of-fact M'Corkindale. "The fact is, that I was anxious to hear about your canvass; and, as there was nothing to do in Glasgow – by the way, Dunshunner, the banks have put on the screw again – I resolved to satisfy my own curiosity in person. I arrived this morning, and Miss Binkie has been kind enough to ask me to stay breakfast."

"I am sure both papa and I are always happy to see Mr M'Corkindale," said Margaret, impressively.

"I am afraid," said I, "that I have interrupted your music: I did not know, M'Corkindale, that you were so eminent a performer."

"I hold with Aristotle," replied Bob modestly, "that music and political economy are at the head of all the sciences. But it is very seldom that one can meet with so accomplished a partner as Miss Binkie."

"Oh, ho!" thought I. But here the entrance of the Provost diverted the conversation, and we all sat down to breakfast. Old Binkie was evidently dying to know the result of my interview on the previous evening, but I was determined to keep him in the dark. Bob fed like an ogre, and made prodigious efforts to be polite.

After breakfast, on the pretext of business we went out for a walk. The economist lighted his cigar.

"Snug quarters these, Dunshunner, at the Provost's."

"Very. But, Bob, things are looking rather well here. I had a negotiation last night which has as good as settled the business."

"I am very glad to hear it – Nice girl, Miss Binkie; very pretty eyes, and a good foot and ankle."

"An unexceptionable instep. What do you think! – I have actually discovered the Clique at last."

"You don't say so! Do you think old Binkie has saved money?"

"I am sure he has. I look upon Dreepdaily as pretty safe now; and I propose going over this afternoon to Drouthielaw. What would you recommend?"

"I think you are quite right; but somebody should stay here to look after your interests. There is no depending upon these fellows. I'll tell you what – while you are at Drouthielaw I shall remain here, and occupy your quarters. The Committee will require some man of business to drill them in, and I don't care if I spare you the time."

I highly applauded this generous resolution; at the same time I was not altogether blind to the motive. Bob, though an excellent fellow in the main, did not usually sacrifice himself to his friends; and I began to suspect that Maggie Binkie – with whom, by the way, he had some previous acquaintance – was somehow or other connected with his enthusiasm. As matters stood, I of course entertained no objection: on the contrary, I thought it no breach of confidence to repeat the history of the nest-egg.

Bob pricked up his ears.

"Indeed!" said he; "that is a fair figure as times go; and, to judge from appearances, the stock in trade must be valuable."

"Cargoes of sugar," said I, "oceans of rum, and no end whatever of molasses!"

"A very creditable chairman, indeed, for your Committee, Dunshunner," replied Bob. "Then I presume you agree that I should stay here, whilst you prosecute your canvass?"

I assented, and we returned to the house. In the course of the forenoon the list of my Committee was published, and, to the great joy of the Provost, the names of Thomas Gill, Alexander M'Auslan, and Simon Shanks appeared. He could not, for the life of him, understand how they had all come forward so readily. A meeting of my friends was afterwards held, at which I delivered a short harangue upon the constitution of 1688, which seemed to give general satisfaction; and before I left the room, I had the pleasure of seeing the Committee organised, with Bob officiating as secretary. It was the opinion of every one that Pozzlethwaite had not a chance. I then partook of a light luncheon, and after bidding farewell to Miss Binkie, who, on the whole, seemed to take matters very coolly, I drove off for Drouthielaw. I need not relate my adventures in that respectable burgh. They were devoid of any thing like interest, and not quite so satisfactory in their result as I could have wished. However, the name of Gills was known even at that distance, and his views had considerable weight with some of the religious denominations. So far as I was concerned, I had no sinecure of it. It cost me three nights' hard drinking to conciliate the leaders of the Anabaptists, and at least three more before the chiefs of the Antinomians would surrender. As to the Old Light gentry, I gave them up in despair, for I could not hope to have survived the consequences of so serious a conflict.

CHAPTER V

Parliament was at length dissolved; the new writs were issued, and the day of nomination fixed for the Dreepdaily burghs. For a time it appeared to myself, and indeed to almost every one else, that my return was perfectly secure. Provost Binkie was in great glory, and the faces of the unknown Clique were positively radiant with satisfaction. But a storm was brewing in another quarter, upon which we had not previously calculated.

The Honourable Mr Pozzlethwaite, my opponent, had fixed his head-quarters in Drouthielaw, and to all appearance was making very little progress in Dreepdaily. Indeed, in no sense of the word could Pozzlethwaite be said to be popular. He was a middle-aged man, as blind as a bat, and, in order to cure the defect, he ornamented his visage with an immense pair of green spectacles, which, it may be easily conceived, did not add to the beauty of his appearance. In speech he was slow and verbose, in manner awkward, in matter almost wholly unintelligible. He professed principles which he said were precisely the same as those advocated by the late Jeremy Bentham; and certainly, if he was correct in this, I do not regret that my parents omitted to bring me up at the feet of the utilitarian Gamaliel. In short, Paul was prosy to a degree, had not an atom of animation in his whole composition, and could no more have carried a crowd along with him than he could have supported Atlas upon his shoulders. A portion, however, of philosophic weavers, and a certain section of the Seceders had declared in his favour; and, moreover, it was just possible that he might gain the suffrages of some of the Conservatives. Kittleweem, the Tory burgh, had hitherto preserved the appearance of strict neutrality. I had attempted to address the electors of that place, but I found that the hatred of Dreepdaily and of its Clique was more powerful than my eloquence; and, somehow or other, the benighted savages did not comprehend the merits of the Revolution Settlement of 1688, and were as violently national as the Celtic race before the invention of trews. Kittleweem had equipped half a regiment for Prince Charles in the Forty-five, and still piqued itself on its staunch Episcopacy. A Whig, therefore, could hardly expect to be popular in such a den of prejudice. By the advice of M'Corkindale, I abstained from any further efforts, which might possibly have tended to exasperate the electors, and left Kittleweem to itself, in the hope that it would maintain an armed neutrality.

And so it probably might have done, but for an unexpected occurrence. Two days before the nomination, a new candidate appeared on the field. Sholto Douglas was the representative of one of the oldest branches of his distinguished name, and the race to which he more immediately belonged had ever been foremost in the ranks of Scottish chivalry and patriotism. In fact, no family had suffered more from their attachment to the cause of legitimacy than the Douglases of Inveriachan. Forfeiture after forfeiture had cut down their broad lands to a narrow estate, and but for an unexpected Indian legacy, the present heir would have been marching as a subaltern in a foot regiment. But a large importation of rupees had infused new life and spirit into the bosom of Sholto Douglas. Young, eager, and enthusiastic, he determined to rescue himself from obscurity; and the present state of the Dreepdaily burghs appeared to offer a most tempting opportunity. Douglas was, of course, Conservative to the backbone; but, more than that, he openly proclaimed himself a friend of the people, and a supporter of the rights of labour.

"Confound the fellow!" said Bob M'Corkindale to me, the morning after Sholto's address had been placarded through the burghs, "who would have thought of an attack of this kind from such a quarter. Have you seen his manifesto, Dunshunner?"

"Yes – here it is in the Patriot. The editor, however, gives him it soundly in the leading article. I like his dogmatic style and wholesale denunciation of the Tories."

"I'll tell you what it is, though – I look upon this as any thing but a joke. Douglas is evidently not a man to stand upon old aristocratic pretensions. He has got the right sow by the ear this time, and, had he started a little earlier, might have roused the national spirit to a very unpleasant pitch. You observe what he says about Scotland, the neglect of her local interests, and the manner in which she has been treated, with reference to Ireland?"

"I do. And you will be pleased to recollect that but for yourself, something of the same kind would have appeared in my address."

"If you mean that as a reproach, Dunshunner, you are wrong. How was it possible to have started you as a Whig upon patriotic principles?"

"Well – that's true enough. At the same time, I cannot help wishing that we had said a word or two about the interests to the north of the Tweed."

"What is done cannot be undone. We must now stick by the Revolution Settlement."

"Do you know, Bob, I think we have given them quite enough of that same settlement already. Those fellows at Kittleweem laughed in my face the last time that I talked about it, and I am rather afraid that it won't go down on the hustings."

"Try the sanatory condition of the towns, then, and universal conciliation to Ireland," replied the Economist. "I have given orders to hire two hundred Paddies, who have come over for the harvest, at a shilling a-head, and of course you may depend upon their voices, and also their shillelahs, if needful. I think we should have a row. It would be a great matter to make Douglas unpopular; and, with a movement of my little finger, I could turn out a whole legion of navigators."

"No, Bob, you had better not. It is just possible they might make a mistake, and shy brickbats at the wrong candidate. It will be safer, I think, to leave the mob to itself: at the same time, we shall not be the worse for the Tipperary demonstration. And how looks the canvass?"

"Tolerably well, but not perfectly secure. The Clique has done its very best, but at the same, time there is undeniably a growing feeling against it. Many people grumble about its dominion, and are fools enough to say that they have a right to think for themselves."

"Could you not circulate a report that Pozzlethwaite is the man of the Clique?"

"The idea is ingenious, but I fear it would hardly work. Dreepdaily is well known to be the head-quarters of the confederation, and the name of Provost Binkie is inseparably connected with it."

"By the way, M'Corkindale, it struck me that you looked rather sweet upon Miss Binkie last evening."

"I did. In fact I popped the question," replied Robert calmly.

"Indeed! Were you accepted?"

"Conditionally. If we gain the election she becomes Mrs M'Corkindale – if we lose, I suppose I shall have to return to Glasgow in a state of celibacy."

"A curious contract, certainly! Well, Bob, since your success is involved in mine, we must fight a desperate battle."

"I wish, though, that Mr Sholto Douglas had been kind enough to keep out of the way," observed M'Corkindale.

The morning of the day appointed for the nomination dawned upon the people of Dreepdaily with more than usual splendour. For once, there was no mist upon the surrounding hills, and the sky was clear as sapphire. I rose early to study my speech, which had received the finishing touches from M'Corkindale on the evening before; and I flatter myself it was as pretty a piece of Whig rhetoric as ever was spouted from a hustings. Toddy Tam, indeed, had objected, upon seeing a draft, that "there was nae banes intil it;" but the political economist was considered by the committee a superior authority on such subjects to Gills. After having carefully conned it over, I went down stairs, where the whole party were already assembled. A large blue and yellow flag, with the inscription, "Dunshunner and the Good Cause!" was hung out from the window, to the intense delight of a gang of urchins, who testified to the popularity of the candidate by ceaseless vociferation to "poor out." The wall opposite, however, bore some memoranda of an opposite tendency, for I could see some large placards, newly pasted up, on which the words, "Electors of Dreepdaily! you are sold by the Clique!" were conspicuous in enormous capitals. I heard, too, something like a ballad chanted, in which my name seemed to be coupled, irreverently, with that of the independent Gills.

Provost Binkie – who, in common with the rest of the company, wore upon his bosom an enormous blue and buff cockade, prepared by the fair hands of his daughter – saluted me with great cordiality. I ought to observe that the Provost had been kept as much as possible in the dark regarding the actual results of the canvass. He was to propose me, and it was thought that his nerves would be more steady if he came forward under the positive conviction of success.

"This is a great day, Mr Dunshunner – a grand day for Dreepdaily," he said. "A day, if I may sae speak, o' triumph and rejoicing! The news o' this will rin frae one end o' the land to the ither – for the e'en o' a' Scotland is fixed on Dreepdaily, and the stench auld Whig principles is sure to prevail, even like a mighty river that rins down in spate to the sea!"

I justly concluded that this figure of speech formed part of the address to the electors which for the two last days had been simmering in the brain of the worthy magistrate, along with the fumes of the potations he had imbibed, as incentives to the extraordinary effort. Of course I took care to appear to participate in his enthusiasm. My mind, however, was very far from being thoroughly at ease.

As twelve o'clock, which was the hour of nomination, drew near, there was a great muster at my committee-room. The band of the Independent Tee-totallers, who to a man were in my interest, was in attendance. They had been well primed with ginger cordial, and were obstreperous to a gratifying degree.

Toddy Tam came up to me with a face of the colour of carnation.

"I think it richt to tell ye, Mr Dunshunner, that there will be a bit o' a bleeze ower yonder at the hustings. The Kittleweem folk hae come through in squads, and Lord Hartside's tenantry have marched in a body, wi' Sholto Douglas's colours flying."

"And the Drouthielaw fellows – what has become of them?"

"Od, they're no wi' us either – they're just savage at the Clique! Gudesake, Mr Dunshunner, tak tent, and dinna say a word aboot huz. I intend mysell to denounce the body, and may be that will do us gude."

I highly approved of Mr Gills' determination, and as the time had now come, we formed in column, and marched towards the hustings with the tee-total band in front, playing a very lugubrious imitation of "Glorious Apollo."

The other candidates had already taken their places. The moment I was visible to the audience, I was assailed by a volley of yells, among which, cries of "Doun wi' the Clique!" – "Wha bought them?" – "Nae nominee!" – "We've had eneuch o' the Whigs!" etcetera, were distinctly audible. This was not at all the kind of reception I had bargained for; – however, there was nothing for it but to put on a smiling face, and I reciprocated courtesies as well as I could with both of my honourable opponents.

During the reading of the writ and the Bribery Act, there was a deal of joking, which I presume was intended to be good-humoured. At the same time there could be no doubt that it was distinctly personal. I heard my name associated with epithets of any thing but an endearing description, and, to say the truth, if choice had been granted, I would far rather have been at Jericho than in the front of the hustings at Dreepdaily. A man must be, indeed, intrepid, and conscious of a good cause, who can oppose himself without blenching to the objurgation of an excited mob.

The Honourable Paul Pozzlethwaite, on account of his having been the earliest candidate in the field, was first proposed by a town-councillor of Drouthielaw. This part of the ceremony appeared to excite but little interest, the hooting and cheering being pretty equally distributed.

It was now our turn.

"Gang forrard, Provost, and be sure ye speak oot!" said Toddy Tam; and Mr Binkie advanced accordingly.

Thereupon such a row commenced as I never had witnessed before. Yelling is a faint word to express the sounds of that storm of extraordinary wrath which descended upon the head of the devoted Provost. "Clique! Clique!" resounded on every side, and myriads of eyes, ferocious as those of the wild-cat, were bent scowlingly on my worthy proposer. In vain did he gesticulate – in vain implore. The voice of Demosthenes – nay, the deep bass of Stentor himself – could not have been heard amidst that infernal uproar; so that, after working his arms for a time like the limbs of a telegraph, and exerting himself until he became absolutely swart in the face, Binkie was fain to give it up, and retired amidst a whirlwind of abuse.

"May the deil fly awa' wi' the hail pack o' them!" said he, almost blubbering with excitement and indignation. "Wha wad ever hae thocht to have seen the like o' this? and huz, too, that gied them the Reform Bill! Try your hand at them, Tam, for my heart's amaist broken!"

The bluff independent character of Mr Gills, and his reputed purity from all taint of the Clique, operated considerably in his favour. He advanced amidst general cheering, and cries of "Noo for Toddy Tam!" "Let's hear Mr Gills!" and the like; and as he tossed his hat aside and clenched his brawny fist, he really looked the incarnation of a sturdy and independent elector. His style, too, was decidedly popular —

"Listen tae me!" he said, "and let thae brawlin', braggin', bletherin' idiwits frae Drouthielaw haud their lang clavering tongues, and no keep rowtin' like a herd o' senseless nowte! (Great cheering from Dreepdaily and Kittleweem – considerable disapprobation from Drouthielaw.) I ken them weel, the auld haverils! (cheers.) But you, my freends, that I have dwalt wi' for twenty years, is it possible that ye can believe for one moment that I wad submit to be dictated to by a Clique? (Cries of "no! no!" "It's no you, Tam!" and confusion.) No me? I dinna thank ye for that! Wull ony man daur to say to my face, that I ever colleagued wi' a pack that wad buy and sell the haill of us as readily as ye can deal wi' sheep's-heads in the public market? (Laughter.) Div ye think that if Mr Dunshunner was ony way mixed up wi' that gang, I wad be here this day tae second him? Div ye think – "

Here Mr Gills met with a singular interruption. A remarkable figure attired in a red coat and cocked-hat, at one time probably the property of a civic officer, and who had been observed for some time bobbing about in front of the hustings, was now elevated upon the shoulders of a yeoman, and displayed to the delighted spectators the features of Geordie Dowie.

"Ay, Toddy Tam, are ye there, man?" cried Geordie with a malignant grin. "What was you and the Clique doin' at Nanse Finlayson's on Friday nicht?"

"What was it, Geordie? What was it?" cried a hundred voices.

"Am I to be interrupted by a natural?" cried Gills, looking, however, considerably flushed in the face.

"What hae ye dune wi' the notes, Tam, that the lang chield up by there gied ye? And whaur's your freends, Shanks and M'Auslan? See that ye steek to the window neist time, ma man!" cried Geordie with demoniac ferocity.

This was quite enough for the mob, who seldom require any excuse for a display of their hereditary privileges. A perfect hurricane of hissing, and of yelling arose, and Gills, though he fought like a hero, was at last forced to retire from the contest. Had Geordie Dowie's windpipe been within his grasp at that moment, I would not have insured for any amount the life of the perfidious spy.

Sholto Douglas was proposed and seconded amidst great cheering, and then Pozzlethwaite rose to speak. I do not very well recollect what he said, for I had quite enough to do in thinking about, myself, and the Honourable Paul would have conferred a material obligation upon me, if he had talked for an hour longer. At length my turn came.

"Electors of Dreepdaily!" —

That was the whole of my speech, at least the whole of it that was audible to any one human being. Humboldt, if I recollect right, talks in one of his travels of having somewhere encountered a mountain composed of millions of entangled snakes, whose hissing might have equalled that of the transformed legions of Pandemonium. I wish Humboldt, for the sake of scientific comparison, could have been upon the hustings that day! Certain I am, that the sibilation did not leave my ears for a fortnight afterwards, and even now, in my slumbers, I am haunted by a wilderness of asps! However, at the urgent entreaty of M'Corkindale, I went on for about ten minutes, though I was quivering in every limb, and as pale as a ghost; and in order that the public might not lose the benefit of my sentiments, I concluded by handing a copy of my speech, interlarded with fictitious cheers, to the reporter for the Dreepdaily Patriot. That document may still be seen by the curious in the columns of that impartial newspaper.

I will state this for Sholto Douglas, that he behaved like a perfect gentleman. There was in his speech no triumph over the discomfiture which the other candidates had received; on the contrary, he rather rebuked the audience for not having listened to us with greater patience. He then went on with his oration. I need hardly say it was a national one, and it was most enthusiastically cheered.

All that I need mention about the show of hands is, that it was not by any means hollow in my favour.

That afternoon we were not quite so lively in the Committee-room as usual. The serenity of Messrs Gills, M'Auslan, and Shanks, – and, perhaps, I may add of myself – was a good deal shaken by the intelligence that a broadside with the tempting title of "Full and Particular Account of an interview between the Clique and Mr Dunshunner, held at Nanse Finlayson's Tavern, on Friday last, and how they came to terms. By an Eyewitness," was circulating like wildfire through the streets. To have been beaten by a Douglas was nothing, but to have been so artfully entrapped by a bauldy!

Provost Binkie, too, was dull and dissatisfied. The reception he had met with in his native town was no doubt a severe mortification, but the feeling that he had been used as a catspaw and implement of the Clique, was, I suspected, uppermost in his mind. Poor man! We had great difficulty that evening in bringing him to his sixth tumbler.

Even M'Corkindale was hipped. I own I was surprised at this, for I knew of old the indefatigable spirit and keen energy of my friend, and I thought that with such a stake as he had in the contest, he would even have redoubled his exertions. Such, however, was not the case.

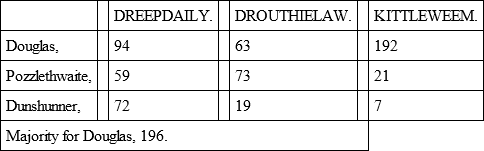

I pass over the proceedings at the poll. From a very early hour it became perfectly evident that my chance was utterly gone; and, indeed, had it been possible, I should have left Dreepdaily before the close. At four o'clock the numbers stood thus: —

We had an awful scene in the Committee-room. Gills, who had been drinking all day, shed copious floods of tears; Shanks was disconsolate; and M'Auslan refused to be comforted. Of course I gave the usual pledge, that on the very first opportunity I should come forward again to reassert the independence of the burghs, now infamously sacrificed to a Conservative; but the cheering at this announcement was of the very faintest description, and I doubt whether any one believed me. Two hours afterwards I was miles away from Dreepdaily.