полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 61, No. 377, March 1847

Aquilius. – Truly, in many places Horace delights to paint this one individual spot. We have in all, the wood, the waters from their higher banks, making falls such as to induce sleep, the garden with its shade, and its fountain, near the house, this continual “aquæ fons.” Such as was his “Fons Bandusiæ,” not fons a mere spring, but sanctified by architectural art, as well as feeling.

“Fies nobilium tu quoque fontium,Me dicente cavis impositam illicemSaxis, unde loquacesLymphæ desiliunt tuæ.”But listen to what he desired to possess, and did possess.

“Hoc erat in votis, modus agri non ita magnus,Hortus ubi, et tecto vicinus jugis aquæ fons,Et paulum sylvæ super his foret.”Is he describing his Sabine villa? – I have a sketch on its site – and there is now, whatever there may have been in his days, a high bank, over which the water still falls, (I believe from the Digentia) which by conduits supplied the house, and cattle returned from their labour, and the flocks. There is a small cascade filling a marble basin (the fountain) and thence flowing off through the garden. Perhaps he had in these descriptions one or two scenes in his mind’s eye much alike. A poet’s geography shifts its scenery ad libitum. But see what his Sabine farm was.

Curate. – I remember it.

“Scribetur tibi forma loquaciter, et situs agri.”

But does he not in that passage make rivus a river? —

“Fons etiam rivo dare nomen idoneus, ut nec

Frigidior Thracam, nec purior ambiat Hebrus.”

Aquilius. – The river was the Digentia, the cold Digentia.

“Me quoties reficit gelidus Digentia rivus.”

It may be here a river, but not certainly. Do you suppose he went down in sight of the whole neighbourhood to bathe in the little river? for little river it is, and cold enough, too; for I have bathed in it, and can testify of its coldness. Would you take him, 1 say, down from his house to the river itself, when he had it conveyed to his own home by a rivus, or channel, and by a fons such as has been described, from which, without doubt, he was supplied with water enough for his hot and his cold baths? The gelidus Digentia rivus, I well know, and, as I said, bathed in it. A countryman seeing me, cried out, “Fa morir!” The Italians now (at least inland) never bathe; they have a perfect hydrophobia. Few even wash themselves. I asked a boy, whom we took about with us to carry our sketching materials, when he had last washed his face. He confessed he had never washed it, and that nobody did.

Curate. – We know Horace delighted in Tibur, – his “Tibur argeo, positum colono.” In the passage criticised in the Pentameron, I shall always see Tivoli, with its wood, its rocks, and cascatelle. He had the scene before him when he wrote, —

“ego laudo ruris amæni

Rivos; et museo circumlita saxa, nemusque.”

Tibur still; its rocks, woods, and rivus again; and perhaps the “nemus” was “Tiburni lucus.”

Aquilius. – Perhaps a line in this epistle from the lover of country to the lover of town, may throw some light on “obliquo” and “trepidare,” if indeed he has the scene in his eye.

“Purior in vicis aqua tendit rumpere plumbum,Quam que per pronum trepidat cum murmure rivum.”Great indeed is the difference, whether the water passes through a leaden pipe, or by the rivers, a mere direction by a channel open to the sky, and whose bed is the rock.

But there is a passage which still more clearly, I think, marks the distinction between the rivus and the river. The poet invites Mæcenas to the country, and tells him, —

“Jam pastor umbras cum grege languidoRivumque fessus querit, et horridiDumeta Silvani, caretqueRipa vagis taciturna ventis.”Now, if the shepherd had driven his flock to the river, all bleating and languid with heat, the bank of the river would scarcely have been taciturn; doubtless the shepherd sought the “fontem,” into which the water was conveyed, and under shade, a place not exposed to the sun, or the wind, as was the ripa, the river’s bank. And besides, in this passage, the rivos and the ripa are certainly spoken of as two separate places.

Here our friend and host began to mutter a little. He was evidently going over his model-farm, while we were at the Sabine. He now talked quicker – “John,” (so he always called his hind, his factotum,) “plant ’em a little farther apart, d’ye see, and trench up well.” “That’s the way.” “Now, John, d’ye know how – to clap an old head on young shoulders – why dig a trench the width of the spade, from the stem of an apple-tree, and fill up with good vegetable mould. First pollard your tree, John.” “That’s it, John.” This and more was said, with a few sleepy interruptions; he soon awoke, and said with an amusing indifference, – “Well, any more news of Catullus?”

Aquilius. – We left Catullus asleep some time ago, and thinking it probable that you and he might wake at the same time, we determined to wait for you both, and, in the meanwhile, we have been discussing a passage in Horace, of which, (for we will not now renew the discussion,) I will one day hear your opinion. A very favourite author, however, of yours, doubts the felicity of Horace in the choice of words.

Curate. – And in the structure of his sentences, and says, “How simple in comparison are Catullus and Lucretius.”

Gratian. – Indeed! now I think that is but finding one fault, for the choice of words and construction of sentences go pretty much together. An ill-constructed sentence can hardly have a good choice of words, for it is most probably unmusical, and that fault would make the choice a jumble. If the words were nonsense in Milton, the music of them would make you believe he could have used no other. They are breathed out so naturally; take the first line of Paradise Lost – it is in this manner perfect. Good words are, to good thoughts, what the stars are to the night, sunshine to the brook, flowers to the field, and foliage to the woods; clothing what is otherwise bare, giving glory to the dark, and to the great and spacious; investing the rugged with grace, and adding the vigour and motion of life to the inanimate, the motionless, and the solid. I must defend my friend Horace against all comers.

“ – rura, quæ Liris quietâ

Mordet aquâ, taciturnus amnis.”

Is there a bad choice of words there? How insidiously the silent river indents the banks with its quiet water, and how true to nature! It is not your turbulent river that eats into the land, (it may overflow it,) but that ever heavy weight of the taciturn rivers, running not in a rocky bed, but through a deep soft soil.

Curate. – You are lucky in your quotation, for we were discussing some such matter. Horace is particularly happy in his river scenes. Did not he know the value of his own words – he thus speaks of them:

“Verba loquor socianda chordis.”

Aquilius. – Yes, but he speaks of them as immortal. “Ne credas interitura.” But if the “socianda chordis,” means they are to be set to music, I deny that music is or there has long ago been a divorce. I am told, the more manifest the nonsense, the better the song.

“Married to immortal verse,”

Gratian. – Then I leave you to sing it, and reserve your sense and sense-verses for to-morrow. But it cannot be till the evening, for I must attend an agricultural meeting in the morning, some distance off. Would you believe it, I have to defend my own statement. A stupid fellow said publicly, that he would not believe that the produce of my Belgian carrots, which you saw, was 360 lbs. per land-yard, which is at the rate of 25 tons, 14 cwt. 1 qr. 4 lbs. per acre. There are people who will doubt every thing. You see they doubt what I say of my carrots, and what Horace says of his own words. – So, good-night.

This “good night,” Eusebius, was not the abrupt leave-taking which it may here appear. For our friend’s habit was to close the day not unthankful. We regularly retired to the dining-room, where the servants and family were assembled, and prayers were read. So that this “good-night” of our excellent host were but his last worldly and social words. And if devotion, and most kind feelings towards all creatures – man and beast – can ensure pleasant and healthful sleep, his pillow is a charm against comfortless dreams and rheumatic pains.

There we leave him – and if, Eusebius, you are amused with this our chat, you may look again for Noctes Catullianæ.

Postscript. – This should have gone to you, my dear Eusebius, two days ago, but by some accident it was left out of the post-bag. By the neglect, however, I am enabled to tell you that our friend the Curate is in trouble: the very trouble, too, which I foresaw. He came to us this morning with a very long face, and told us that yesterday, on going as usual to his parochial Sunday school, he was surprised that nearly all the bigger girls were absent; that the mistress of the school did not receive him with her usual respect; that the three maiden ladies, Lydia Prateapace, Clarissa Gadabout, and Barbara Brazenstare, were at the farther end of the room, affectedly busy with the children; that seeing him, they slightly acknowledged his presence, as Goldsmith well expresses it, by a “mutilated curtsey.” He approached them, and expressed his surprise at the absence of the elder children. Prateapace looked first down, then away from him, and said it was no business of hers to question their parents. Miss Gadabout added, that every body knew the reason. And Brazenstare looked him boldly in the face, and said, she supposed nobody knew so well as himself. Prateapace put in her word, that now he was come, there was no need of their presence, as there were not too many to teach. Upon which Gadabout cried, “Then let us be off: it is quite time we should.” And as they were moving off, Brazenstare turned round and asked him, mutteringly, if he intended to kiss the schoolmistress. Upon this, he went to some of the parents to inquire respecting the absence of their daughters, and little satisfaction could he get. They didn’t like to say – but people did say – indeed it was all about the township – that they were quite as well at home, for that they might learn more than the book taught – for that his honour had been reproved by good Mr. G. for too great familiarity.

So ends the matter, or rather such is the position of affairs at present – the Curate has come to consult what is to be done. I tell him, that if he knows what he is about, it will proceed with some violence, then an opposition, and end with offerings of bouquets, and perhaps the presentation of a piece of plate. Gratian tells him he hopes nothing so bad as that will come to pass – the Curate almost fears it will, and is vexed at his present awkward position.

You, Eusebius, already see enough mischief in it to delight you; you are, I know, laughing immoderately, and determine to write the inscription for the plate in perspective. Adieu, ever yours. Aquilius.

1

See No. CCCLXXIII, page 555.

2

See next page.

3

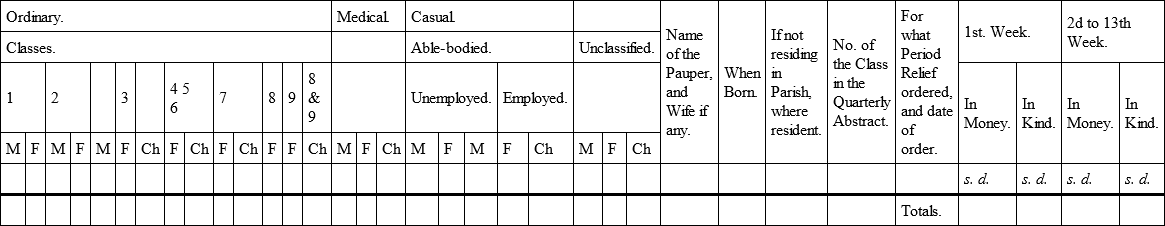

Form 25 (a.)

Weekly Out-Door Relief List, for the quarter ending 18 , District. Relieving Officer.

It is possible that a union maybe found in which the number of poor are so few, as to allow of the four orders of poor – the Ordinary, the Medical, the Casual, and the Unclassified – to be contained in one book; but in general it would be necessary to separate them and to appropriate a book to each order; and there are parishes so large, and in which certain classes of poor abound, as to require separate books for those particular cases.

4

Elia

5

If the reader will refer again to the form of “Relief List,” he will perceive that there are three general divisions, named severally, ordinary, medical, and casual. These terms were preserved, because they are well known in actual practice, rather than because they express a really broad distinction. The ordinary relief list is supposed to contain all those recipients of relief who are likely to continue chargeable for a long period. But the distinction attempted to be drawn between those who may require relief for a long and those who require it for a short period only, depends upon circumstances too vague and variable to be of any practical utility. These objections are not applicable to the generic term “medical.”

6

A tradesman is not a shopkeeper, but a mechanic who is skilled in his particular branch of industry.

7

In other words, that he will be condemned to slavery, and employed on the public works in wheeling a barrow.

8

The belief in hard men, i. e. of men whose skins were impervious to a musket or pistol ball, was extremely prevalent during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They could be killed only by a silver bullet. Fitzgerald, the notorious duellist and murderer, in the middle of the last century, was said to have been a hard man. – See Thoms’ Anecdotes and Traditions, printed for the Camden Society, p. 111.

9

It must be borne in mind that the priests here alluded to are Danish.

10

Junker (pronounced Yunker,) the title given to a son of noble family. Fröken (dimin. of Frue, madam, lady; Ger. Fräulein) is the corresponding title of a young lady of rank.

11

Madam, applied strictly to ladies of rank only.

12

The Nisse of the Scandinavian nations is, in many respects, the counterpart of the Scottish Brownie, while, in others, he occasionally resembles the Devonian and Cornish Pixie and Portune. He is described as clad in gray, with a pointed red cap. Having once taken up his abode with a family, it is not easy to dislodge him, as is evident from the following anecdote: – A man, whose patience was exhausted by the mischievous pranks of a Nisse that dwelt in his house, resolved on changing his habitation, and leaving his troublesome guest to himself. Having packed his last cart-load of chattels, he chanced to go to the back of his cart, to see whether all was safe, when, to his dismay, the Nisse popped his head out of a tub, and with a loud laugh, said, “See, we flit to-day,” (See, idag flytte vi.) —Thiele, Danske Folkesagn, i. p. 134, and Athenæum, No. 991.

There are also ship Nisses, whose functions consist in shadowing out, as it were, by night all the work that is to be performed the following day, – to weigh or cast anchor, to hoist or lower the sails, to furl or reef them – all which operations are forerunners of a storm. For the duty even of a swabber, he does not consider himself too high, but washes the deck most delicately clean. Some well-informed persons maintain that this spiritus navalis, or nautical goblin, proves himself of kindred race with the house or land Nisse by his roguish pranks. Sometimes he turns the vane, sometimes extinguishes the light in the binnacle, plagues the ship’s dog, and if there chance to be a passenger on board who cannot bear the sea, the rogue will appear before him with heart-rending grimaces retching in the bucket. If the ship is doomed to perish, he jumps overboard in the night, and either enters another vessel or swims to land.

13

According to the Germanic nations, the devil has a horse’s, not a cloven foot.

14

In the original, “Ole Luköje,” i. e., Olave Shut-eye, a personage as well known by name to the children of Denmark, as the dustman is to those of England.

15

She was no doubt habited en Amazone, as was the fashion in Denmark about the date to which our story refers. At a much later period, Matilda (sister of our George III.) Queen of Christian VII. rode in a garb nearly resembling a man’s.

16

Viz. a fox, in allusion to Mikkel’s surname of Foxtail.

17

Two places of public resort and great beauty in the neighbourhood of Copenhagen. On St. John’s (Hans’) eve, the former place is thronged with the inhabitants of the capital and vicinity, for the purpose of drinking the waters of a well held in great esteem.

18

Reise nach Java, und Ausflüge nach den Inseln Madura und St. Helena. Von Dr. Eduard Selberg. Oldenburg and Amsterdam: 1846.

19

Trade and Travel in the Far East. London: 1846.

20

Notes to “Peveril of the Peak.”

21

Notes to “Oliver Newman.”

22

Trial of Charles I. and the Regicides, which I see referred to in “Oliver Newman,” but I have not the book myself.

23

London Times of that date.

24

State Trials, ii. 389.

25

Somers’ Tracts, vi. 339.

26

Carlyle and Clarendon.

27

Carlyle.

28

Carlyle.

29

Clarendon, iii. 590.

30

Percy’s Reliques, 121.

31

Fasti Oxon. ii. 79.

32

Letters and Speeches, &c. by Carlyle.

33

Fasti Oxon. ii. 79.

34

Carlyle.

35

Fasti Oxon, ii. p. 79. Anno 1649.

36

Evelyn’s Memoirs, i. 308.

37

Notes to Peveril of the Peak.

38

Sir Thomas Herbert’s Two Last Years, p. 189.

39

State Trials, ii. 886.

40

Lives of the Queens, vol. viii.

41

Holmes’ American Annals.

42

Isaiah xvi. 3.

43

Rev. xi. 8.

44

Rev. xiii. 18.

45

Holmes’ American Annals, in Ann. Also, Notes to “Oliver Newman.”

46

Gatherings from Spain, by Richard Ford. London, 1846.

An Overland Journey to Lisbon, &c., by T. M. Hughes. London, 1847.