полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 60, No. 370, August 1846

This marvellous dialogue, from which we have taken with our finger and thumb a tit-bit here and there, might be the text for inexhaustible annotation. It occupies no more than two pages; but, as Gibbon has said of Tacitus, "they are the pages of Soyer." Every topic within the range of human knowledge is touched, by direct exposition or collateral allusion. The metaphysician and the theologian, the physiologist and the moralist, are all challenged to investigate its dogmas, which, let us forewarn them, are so curtly, positively, and oracularly propounded, as, if orthodox, to need no commentary; and if heterodox, to demand accumulated mountains of controversy to overwhelm them. For he, we believe, can hardly be deemed a mean opponent, unworthy of a foeman's steel-pen, who has at his fingers' ends "Mullets à la Montesquieu," "Fillets of Haddock à la St Paul," "Saddle of Mutton à la Mirabeau," "Ribs of Beef à la Bolingbroke," "Pounding Soufflé à la Mephistopheles," "Woodcock à la Staël," and "Filets de Bœuf farcis à la Dr Johnson."

The constitution of English cookery is precisely similar to the constitution of the English language. Both were prophetically sketched by Herodotus in his description of the army of Xerxes, which gathered its numbers, and strength, and beauty, from "all the quarters in the shipman's card." That imperishable mass of noble words – that glorious tongue in which Soyer has prudently written the "Gastronomic Regenerator," is in itself an unequalled specimen of felicitous cookery. The dishes which furnished the most recherché dinner Soyer ever dressed, the "Diner Lucullusian à la Sampayo," being resolved into the chaos whence they arose in faultless proportions and resistless grace, would not disclose elements and ingredients more heterogenous, remote, and altered from their primal nature, than those which go to the composition of the few sentences in which he tells us of this resuscitation of the cæna of Petronius. A thousand years and a thousand accidents, the deepest erudition and the keenest ingenuity, the most delicate wit and most outrageous folly, have been co-operating in the manufacture of the extraordinary vocabulary which has enabled the Regenerator himself to concoct the following unparalleled receipt for

"THE CELESTIAL AND TERRESTRIAL CREAM OF GREAT BRITAIN"Procure, if possible, the antique Vase of the Roman Capitol; the Cup of Hebe; the Strength of Hercules; and the Power of Jupiter;"

"Then proceed as follows:– "

"Have ready the chaste Vase (on the glittering rim of which three doves are resting in peace), and in it deposit a Smile from the Duchess of Sutherland, from which Terrestrial Déesse it will be most graceful; then add a Lesson from the Duchess of Northumberland; the Happy Remembrance of Lady Byron; an Invitation from the Marchioness of Exeter; a Walk in the Fairy Palace of the Duchess of Buckingham; an Honour of the Marchioness of Douro; a Sketch from Lady Westmoreland; Lady Chesterfield's Conversation; the Deportment of the Marchioness of Aylesbury; the Affability of Lady Marcus Hill; some Romances of Mrs Norton; a Mite of Gold from Miss Coutts; a Royal Dress from the Duchess of Buccleuch; a Reception from the Duchess of Leinster; a Fragment of the Works of Lady Blessington; a Ministerial Secret from Lady Peel; a Gift from the Duchess of Bedford; an Interview with Madame de Bunsen; a Diplomatic Reminiscence from the Marchioness of Clanricarde; an Autocratic Thought from the Baroness Brunow; a Reflection from Lady John Russell; an amiable Word from Lady Wilton; the Protection of the Countess de St Aulaire; a Seraphic Strain from Lady Essex; a poetical gift of the Baroness de la Calabrala; a Welcome from Lady Alice Peel; the Sylph-like form of the Marchioness of Abercorn; a Soirée of the Duchess of Beaufort; a Reverence of the Viscountess Jocelyn; and the Good-will of Lady Palmerston.

"Season with the Piquante Observation of the Marchioness of Londonderry; the Stately Mein of the Countess of Jersey; the Trésor of the Baroness Rothschild; the Noble Devotion of Lady Sale; the Knowledge of the Fine Arts of the Marchioness of Lansdowne; the Charity of the Lady De Grey; a Criticism from the Viscountess of Melville; – with a Musical Accompaniment from the whole; and Portraits of all these Ladies taken from the Book of Celebrated Beauties.

"Amalgamate scientifically; and should you find this Appareil (which is without a parallel) does not mix well, do not regard the expense for the completion of a dish worthy of the Gods!

"Endeavour to procure, no matter at what price, a Virtuous Maxim from the Book of Education of Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Kent; a Kiss from the Infant Princess Alice; an Innocent Trick of the Princess-Royal; a Benevolent Visit from the Duchess of Gloucester; a Maternal Sentiment of Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Cambridge; a Compliment from the Princess Augusta de Mecklenbourg; the future Hopes of the Young Princess Mary; —

"And the Munificence of Her Majesty Queen Adelaide.

"Cover the Vase with the Reign of Her Most Gracious Majesty, and let it simmer for half a century, or more, if possible, over a Fire of Immortal Roses.

"Then uncover, with the greatest care and precision, this Mysterious Vase; garnish the top with the Aurora of a Spring Morning; several Rays of the Sun of France; the Serenity of an Italian Sky; and the Universal Appreciation of the Peace of Europe.

"Add a few Beams of the Aurora Borealis; sprinkle over with the Virgin Snow of Mont Blanc; glaze with an Eruption of Mount Vesuvius, cause the Star of the Shepherd to dart over it; and remove, as quickly as possible, this chef-d'œuvre of the nineteenth century from the Volcanic District.

"Then fill Hebe's Enchanted Cup with a religious Balm, and with it surround this mighty Cream of Immortality;

"Terminate with the Silvery light of the Pale Queen of Night, without disturbing a Ray of the Brilliancy of the brightest Queen of the Day."

Half a century hence, when the simmering over the roseate fire is silent, may we, with M. Soyer, be present to gaze on the happy consummation of the conceptions of his transcendant imagination!

The Regenerator is too conversant with universal history not to know that his book, in crossing the Tweed northwards, approaches a people more familiar with its fundamental principles than any other inhabitants of these Fortunate Isles. England, for any thing we care, may deserve the opprobrious title of perfidious Albion. Scotland – ("Stands Scotland where it did?") – was ever the firm friend of France. Ages ago, when our southern cousins were incessantly fighting, we were constantly dining, with the French. Our royal and noblest families were mingled by the dearest ties with the purest and proudest blood of the adopted land of Mary. For centuries uninterruptedly was maintained an interchange of every gentle courtesy, and every friendly succour; and when the broadsword was not needed to gleam in the front ranks of Gallic chivalry, the dirk never failed to emit the first flash in the onslaughts of Gallic hospitality. The Soyers of those times – dim precursors of the Regenerator – did not disdain to alight on our hungry shores, and leave monuments of their beneficence, which are grateful to this hour in the nostrils and to the palate of prince and peasant. Nay, we shrewdly conjecture that some time-honoured secrets still dwell with us, of which the memory has long since perished in their birth-place. Boastful we may not suffer ourselves to be. But if M. Soyer ever heard of, or dressed or tasted precisely as we have dressed and tasted, what is known to us and a very limited circle of acquaintances as "Lamb-toasty," we shall start instantly from the penultimate habitation of Ultima Thule, commonly known as John O'Groat's House, expressly to test his veracity, and gratify our voracity. Perhaps he may think it would not be too polite in us to transmit him the receipt. Not for a wilderness of Regenerators! Could we unfold to him the awful legend in connexion with it, of which we are almost the exclusive depositaries, the cap so lightly lying on his brow would be projected upwards to the roof by the instantaneous starting of his hair. The Last Minstrel himself, to whom it was narrated, shook his head when he heard it, and was never known to allude to it again; in reference to which circumstance, all that the bitterest malice could insinuate was, that if the story had been worth remembering, he was not likely to have forgotten it. "One December midnight, a shriek" – is probably as far as we can now venture to proceed. There are some descendants of the parties, whose feelings, even after the lapse of five hundred years, which is but as yesterday in a Highlander's genealogy, we are bound to respect. In other five hundred years, we shall, with more safety to ourselves, let them "sup full of horrors."

The Gastronomic Regenerator reminds us of no book so much as the Despatches of Arthur Duke of Wellington. The orders of Soyer emanate from a man with a clear, cool, determined mind – possessing a complete mastery of his weapons and materials, and prompt to make them available for meeting every contingency – singularly fertile in conceiving, and fortunate without a check in executing, sudden, rapid, and difficult combinations – overlooking nothing with his eagle eye, and, by the powerful felicity of his resources, making the most of every thing – matchless in his "Hors-d'Œuvres" – unassailable in his "Removes" – impregnable in his "Pièces de resistance" – and unconquerable with his "Flanks." His directions are lucid, precise, brief, and unmistakeable. There is not a word in them superfluous – or off the matter immediately on hand – or not directly to the point. They are not the dreams of a visionary theorist and enthusiast, but the hard, solid, real results of the vast experience of a tried veteran, who has personally superintended or executed all the operations of which he writes. It may be matter of dispute whether Wellington or Soyer acquired their knowledge in the face of the hotter fire. They are both great Chiefs – whose mental and intellectual faculties have a wonderful similarity – and whose sayings and doings are characterised by an astonishing resemblance in nerve, perspicuity, vigour, and success. In one respect M. Soyer has an advantage over his illustrious contemporary. His Despatches are addressed to an army which as far outnumbers any force every commanded or handled by the Hero of Waterloo, as the stars in the blue empyrean exceed the gas-lamps of London – an army which, instead of diminishing under any circumstances, evinces a tendency, we fear, of steadily swelling its ranks year by year, and day by day – a standing army, which the strong hand of the most jealous republicanism cannot suppress, and which the realization of the bright chimera of universal peace will fail to disband. Before many months are gone, thousands and tens of thousands will be marching and countermarching, cutting and skewering, broiling and freezing, in blind obedience to the commands of the Regenerator. "Peace hath her victories no less than those of war." But it is not to be forgotten that if the sword of Wellington had not restored and confirmed the tranquillity of the world, the carving-knife of Soyer might not have been so bright.

The confidence of Soyer in his own handiwork is not the arrogant presumption of vanity, but the calm self-reliance of genius. There is a deal of good sense in the paragraph which we now quote: —

"Although I am entirely satisfied with the composition, distribution, and arrangement of my book, should some few little mistakes be discovered they will be the more excusable under those circumstances, as in many instances I was unable to devote that tedious time required for correction; and although I have taken all possible care to prescribe, by weight and measure, the exact quantity of ingredients used in the following receipts for the seasoning and preparing of all kinds of comestibles, I must observe that the ingredients are not all either of the same size or quality; for instance, some eggs are much larger than others, some pepper stronger, salt salter, and even some sugar sweeter. In vegetables, again, there is a considerable difference in point of size and quality; fruit is subject to the same variation, and, in fact all description of food is subject to a similar fluctuation. I am far, however, from taking these disproportions for excuses, but feel satisfied, if the medium of the specified ingredients be used, and the receipts in other respects closely followed, nothing can hinder success."

It seems a childish remark to make, that all salts do not coincide in their saltness, nor sugars in their sweetness. The principle, however, which the observation contains within it, is any thing but childish. It implies, that, supposing the accuracy of a Soyer to be nearly infallible, the faith in his instructions must never be so implicit as to supersede the testimony of one's own senses, and the admonitions of one's own judgment. It is with the most poignant recollections that we acknowledge the justice of the Regenerator's caution on this head. We once, with a friend who shared our martyrdom, tried to make onion soup in exact conformity with what was set down in an Oracle of Cookery, which a foul mischance had placed across our path. With unerring but inflecting fidelity, we filled, and mixed, and stirred, and watched, the fatal caldron. The result was to the eye inexpressibly alarming. A thick oily fluid, repulsive in colour, but infinitely more so in smell, fell with a flabby, heavy, lazy stream, into the soup-plate. Having swallowed, with a Laocoonic contortion of countenance, two or three mouthfuls, our individual eyes wandered stealthily towards our neighbour. Evidently we were fellow-sufferers; but pride, which has occasioned so many lamentable catastrophes, made us both dumb and obdurate in our agony. Slowly and sadly, at lengthened intervals, the spoon, with its abominable freight, continued to make silent voyages from the platters to our lips. How long we made fools of ourselves it is not necessary to calculate. Suddenly, by a simultaneous impulse, the two windows of the room favoured the headlong exit of two wretches whose accumulated grievances were heavier than they could endure. Hours rolled away, while the beautiful face of Winandermere looked as ugly as Styx, as we writhed along its banks, more miserably moaning than the hopeless beggar who sighed for the propitiatory obolus to Charon. And from that irrevocable hour we have abandoned onions to the heroines of tragedy. Fools, in spite of all warning, are taught by such a process as that to which we submitted. Wise men, take a hint.

"Nature, says I to myself" – Soyer is speaking – "compels us to dine more or less once a-day." The average which oscillates between the "more" and the "less," it requires considerable dexterity to catch. Having read six hundred pages and fourteen hundred receipts, the question is, where are we to begin? Our helplessness is confessed. Is it possible the Regenerator is, after all, more tantalizing than the Barmecide? No – here is the very aid we desiderate. Our readers shall judge of a

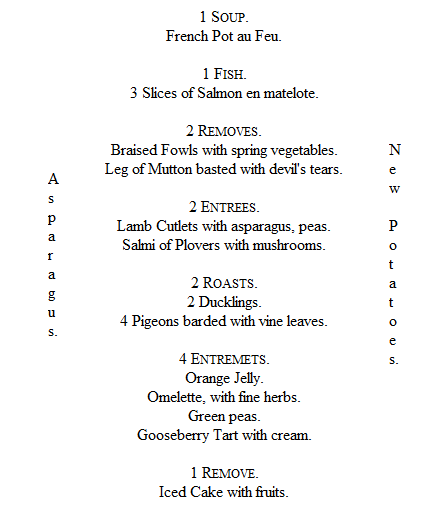

"DINNER PARTY AT HOME."BILL OF FARE FOR EIGHT PERSONS

"Nothing but light wine is drunk at the first course, but at the second my guests are at liberty to drink wines of any other description, intercepting them with several hors-d'œuvres, which are small dishes of French pickled olives and sardines, thin slices of Bologna sausage, fillets of anchovies, ciboulettes, or very small green onions, radishes, &c.; also a plain dressed salade à la Français, (for which see end of the entrées, Kitchen at Home), fromage de brie Neufchatel, or even Windsor cheese, when it can be procured. The coffee and dessert I usually leave to the good taste and economy of my menagere."

We shall be exceedingly curious to hear how many hundred parties of eight persons, upon reading this bill of fare in our pages, will, without loss of time, congregate in order to do it substantial honour. Such clattering of brass and brandishing of steel may strike a new government as symptomatical or preparatory of a popular rising. We may therefore reassure them with the information, that those who sit down with M. Soyer, will have little thought of rising for a long time afterwards.

We have introduced the Gastronomic Regenerator to public notice in that strain which its external appearance, its title, its scheme and its contents, demand and justify. But we must not, even good-humouredly, mislead those for whose use its publication is principally intended. To all intents and purposes M. Soyer's work is strictly and most intelligibly practical. It is as full of matter as an egg is full of meat; and the household which would travel through its multitudinous lessons must be as full of meat as the Regenerator is full of matter. The humblest, as well as the wealthiest kitchen economy, is considered and instructed; nor will the three hundred receipts at the conclusion of the volume, which are more peculiarly applicable to the "Kitchen at Home," be, probably the portion of the book least agreeable and valuable to the general community. For example, just before shaking hands with him, let us listen to M. Soyer, beginning admirably to discourse

Of the Choosing and Roasting of Plain Joints"Here I must claim all the attention of my readers. Many of the profession will, I have no doubt, be surprised that I should dwell upon a subject, which appears of so little importance, saying that, from the plain cook to the most professed, all know how to roast or boil a piece of meat; but there I must beg their pardon. I will instance myself, for, previously to my forming any intention of writing the present work, I had not devoted the time necessary to become professionally acquainted with it, always depending upon my roasting cook, who had constant practice, myself only having the knowledge of whether or not properly done. I have since not only studied it closely, but have made in many respects improvements upon the old system, and many discoveries in that branch which I am sure is the most beneficial to all classes of society, (remembering, as I have before stated, that three parts of the animal food of this country is served either plain-roasted or boiled) My first study was the fire, which I soon perceived as too deep, consumed too much coal, and required poking every half hour, thus sending dust and dirt all over the joints, which were immediately basted to wash it off; seeing plainly this inconvenience, I immediately remedied it by inventing my new roasting fire-place, by which means I saved two hundred-weight of coals per day, besides the advantage of never requiring to be poked, being narrow and perpendicular; the fire is lighted with the greatest facility, and the front of the fire being placed a foot back in the chimney-piece, throws the heat of the fire direct upon the meat, and not out at the sides, as many persons know, from the old roasting ranges. I have many times placed ladies or gentlemen, visiting the club, within two feet of the fire when six large joints have been roasting, and they have been in perfect ignorance that it was near them, until, upon opening the wing of the screen by surprise, they have appeared quite terrified to think they were so near such an immense furnace. My next idea was to discontinue basting, perhaps a bold attempt to change and upset at once the custom of almost all nations and ages, but being so confident of its evil effects and tediousness, I at once did away with it, and derived the greatest benefit (for explanation, see remarks at the commencement of the roasts in the Kitchen of the Wealthy,) for the quality of meat in England is, I may say, superior to any other nation; its moist soil producing fine grass almost all the year round, which is the best food for every description of cattle; whilst in some countries not so favoured by nature they are obliged to have recourse to artificial food, which fattens the animals but decreases the flavour of the meat: and, again, we, must take into consideration the care and attention paid by the farmers and graziers to improve the stock of those unfortunate benefactors of the human family."

How full of milky kindness is his language, still breathing the spirit of that predominant idea – the tranquillisation of the universe by "Copious Dinners!" He has given up "basting" with success. Men may as well give up basting one another. Nobody will envy the Regenerator the bloodless fillets worthily encircling his forehead, should the aspirations of his benevolent soul in his lifetime assume any tangible shape. But if a more distant futurity is destined to witness the lofty triumph, he may yet depart in the confidence of its occurrence. The most precious fruits ripen the most slowly. The sun itself does not burst at once into meridian splendour. Gradually breaks the morning; and the mellow light glides noiselessly along, tinging mountain, forest, and city spire, till a stealthy possession seems to be taken of the whole upper surface of creation, and the mighty monarch at last uprises on a world prepared to expect, to hail, and to reverence his perfect and unclouded majesty.

THE LATE AND THE PRESENT MINISTRY

Our sentiments with regard to the change of policy on the part of Sir Robert Peel and his coadjutors, were early, and we hope forcibly, expressed. We advocated then, as ever, the principle of protection to native industry and agriculture, not as a class-benefit, but on far deeper and more important considerations. We deprecated the rash experiment of departing from a system under which we had flourished so long – of yielding to the clamours of a grasping and interested faction, whose object in raising the cry of cheap bread, was less the welfare of the working man, than the depression of his wages, and a corresponding additional profit to themselves. The decline of agricultural prosperity – inevitable if the anticipations of the free traders should be fulfilled – seems to us an evil of the greatest possible magnitude, and the more dangerous because the operation must be necessarily slow. And in particular, we protested against the introduction of free-trade measures, at a period when their consideration was not called for by the pressure of any exigency, when the demand for labour was almost without parallel, and before the merits of the sliding-scale of duty, introduced by Sir Robert Peel himself in the present Parliament, had been sufficiently tested or observed. Those who make extravagant boast of the soundness and sagacity of their leader cannot deny, that the facts upon which he based his plan of financial reform, were in reality not facts, but fallacies. The political Churchill enunciated his Prophecy of Famine, not hesitatingly nor doubtfully, but in the broadest and the strongest language. Month after month glided away, and still the famine came not; until men, marvelling at the unaccountable delay, looked for it as the ignorant do for the coming of a predicted eclipse, and were informed by the great astrologer of the day that it was put off for an indefinite period! Now, when another and a more beautiful harvest is just beginning, we find that in reality the prophecy was a mere delusion; that there were no grounds whatever to justify any such anticipation, and that the pseudo-famine was a mere stalking-horse, erected for the purpose of concealing the stealthy advance of free-trade.

If this measure of free-trade was in itself right and proper, it required no such paltry accessories and stage tricks to make it palatable to the nation at large. Nay, we go further, and say, that under no circumstances ought the distress of a single year to be assigned as a sufficient reason for a great fiscal change which must derange the whole internal economy and foreign relations of the country, and which must be permanent in its effects. There is, and can be, no such thing as a permanent provision for exigencies. Were it so, the art of government might be reduced to principles as unerring in their operation as the tables of an assurance company – every evil would be provided for before it occurred, and fluctuations become as unknown among us as the recurrence of an earthquake. A famine, had it really occurred, would have been no apology for a total repeal of the corn-laws, though it might have been a good reason for their suspension. As, however, no famine took place, we take the prophecy at its proper value, and dismiss it at once to the limbo of popular delusions; at the same time, we trust that future historians, when they write this chapter of our chronicles, will not altogether overlook the nature of the foundation upon which this change has been placed.