полная версия

полная версияBlackwoods Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 59, No. 365, March, 1846

Mr Moses, senior, turned towards his son one of those expressive looks which Aby, in his boyhood, had always translated – "a good thrashing, my fine fellow, at the first convenient opportunity." Aby, utterly beaten by disappointment, vexation, and fear, roared like a distressed bear.

"Come, come!" said Lord Downy; "matters may not be as bad as they seem. The lad has been cruelly dealt by. I will take care to set him right. I received of your three hundred pounds this morning, Mr Moses, two hundred and fifty; the remaining fifty were secured by Mr Fitzalbert as a bonus. That sum is here. I have the most pressing necessity for it; but I feel it is not for me to retain it for another instant. Take it. I have five-and-twenty pounds more at the Salisbury hotel, which, God knows, it is almost ruin to part with, but they are yours also, if you will return with me. I give you my word I have not, at the present moment, another sixpence in the world. I have a few little matters, however, worth ten times the amount, which I beg you will hold in security, until I discharge the remaining five-and-twenty pounds. I can do no more."

"Vell, as you say, we have been both deceived by a great blackguard, and by that 'ere jackass in the corner. You've shpoken like a gentleman, vich is alvays gratifying to the feelings. To show you that I am not to be outdone in generosity, I accept your terms."

Lord Downy was not moved to tears by this disinterested conduct on the part of Mr Moses, but he gladly availed himself of any offer which would save him from exposure. A few minutes saw them driving back to Oxford Street; Methusaleh and Lord Downy occupying the inside of a cab, whilst Aby was mounted on the box. The features of the interesting youth were not visible during the journey, by reason of the tears that he shed, and the pocket-handkerchief that was held up to receive them.

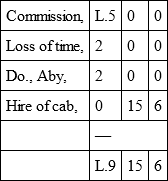

A little family plate, to the value of a hundred pounds, was, after much haggling from Methusaleh, received as a pledge for the small deficiency; which, by the way, had increased since the return of the party to the Salisbury Hotel, to thirty-four pounds fifteen shillings and sixpence; Mr Moses having first left it to Lord Downy's generosity to give him what he thought proper for his trouble in the business, and finally made out an account as follows —

"I hope you thinks," said Methusaleh, packing up the plate, "that I have taken no advantage. Five hundred pounds voudn't pay me for all as I have suffered in mind this blessed day, let alone the vear and tear of body."

Lord Downy made no reply. He was heartsick. He heard upon the stairs, footsteps which he knew to belong to Mr Ireton. That gentleman, put off from day to day with difficulty and fearful bribes, was not the man to melt at the tale which his lordship had to offer instead of cash, or to put up with longer delay. His lordship threw himself into a chair, and awaited the arrival of his creditor with as much calmness as he could assume. The door opened, and Mr Mason entered. He held in his hand a letter, which had arrived by that morning's post. The writing was known. Lord Downy trembled from head to foot as he broke the seal, and read the glad tidings that met his eye. His uncle, the Earl of – , had received his appeal, and had undertaken to discharge his debts, and to restore him to peace and happiness. The Earl of – , a member of the government, had obtained for his erring nephew an appointment abroad, which he gave him, in the full reliance that his promise of amendment should be sacredly kept.

"It shall! it shall!" said his lordship, bursting into tears, and enjoying, for the first time in his life, the bliss of liberty. Need we say that Mr Ireton, to his great surprise, was fully satisfied, and Mr Moses in receipt of his thirty-four pounds fifteen shillings and sixpence, long before he cared to receive the money? These things need not be reported, nor need we mention how Lord Downy kept faith with his relative, and, once rid of his disreputable acquaintances, became himself a reputable and useful man.

Moses and Son dissolved their connexion upon the afternoon of that day which had risen so auspiciously for the junior member. When Methusaleh had completed the packing up of Lord Downy's family plate, he turned round and requested Aby not to sit there like a wretch, but to give his father a hand. He was not sitting there either as a wretch or in any other character. The youth had taken his opportunity to decamp. Leaving the hotel, he ran as fast as he could to the parental abode, and made himself master of such loose valuables as might be carried off, and turned at once into money. With the produce of this stolen property, Aby extravagantly purchased a passage to New South Wales. Landing at Sydney, he applied for and obtained a situation at the theatre. His face secured him all the "sentimental villains;" and his success fully entitles him, at the present moment, to be regarded as the "acknowledged hero" of "domestic (Sydney) melodrama."

VICHYANA

No watering-place so popular in France as Vichy; in England few so little known! Our readers will therefore, we doubt not, be glad to learn something of the sources and resources of Vichy; and this we hope to give them, in a general way, in our present Vichyana. What further we may have to say hereafter, will be chiefly interesting to our medical friends, to whom the waters of Vichy are almost as little known as they are to the public at large. The name of the town seems to admit, like its waters, of analysis; and certain grave antiquaries dismember it accordingly into two Druidical words, "Gurch" and "I;" corresponding, they tell us, to our own words, "Power" and "Water;" which, an' it be so, we see not how they can derive Vichy from this source. Others, with more plausibility, hold Vichy to be a corruption of Vicus. That these springs were known to the Romans is indisputable; and, as they are marked Aquæ calidæ in the Theodosian tables, they were, in all probability, frequented; and the word Vicus, Gallicised into Vichy, would then be the designation of the hamlet or watering-place raised in their neighbourhood. Two of the principal springs are close upon the river; ascertaining, with tolerable precision, not only the position of this Vicus, but also of the ancient bridge, which, in the time of Julius Cæsar, connected, as it now does, the town with the road on the opposite bank of the Allier, (Alduer fl.,) leading to Augusta Nemetum, or Clermont. The road on this side of the bridge was then, as now, the high one (via regia) to Lugdunum, or Lyons.

Vichy, if modern geology be correct, was not always thus a watering-place; but seems, for a long period, to have been a place under water. The very stones prate of Neptune's whereabouts in days of langsyne. No one who has seen what heaps of rounded pebbles are gleaned from the corn-fields, or become familiar with the copious remains of fresh water shells and insects, which are kneaded into the calcareous deposits a little below the surface of the soil, can help fetching back in thought an older and drearier dynasty. Vulcan here, as in the Phlegrian and Avernian plains, succeeded with great labour, and not without reiterated struggles, in wresting the region from his uncle, and proved himself the better earth-shaker of the two; first, by means of subterranean fires, he threw up a great many small islands, which, rising at his bidding, as thick as mushrooms after a thunder-storm, broke up the continuous expanse of water into lakes; and by continual perseverance in this plan, he at last rescued the whole plain from his antagonist, who, marshaling his remaining forces into a narrow file, was fain to retreat under the high banks of the Allier, and to evacuate a large tract of country, which had been his own for many centuries.

Natural History, &cThe natural history of Vichy – that is, so much of it as those who are not naturalists will care to know – is given in a few sentences. Its Fauna contains but few kinds of quadrupeds, and no great variety of birds; amongst reptiles again, while snakes abound as to number, the variety of species is small. You see but few fish at market or at table; and a like deficiency of land and fresh water mollusks is observable; while, in compensation for all these deficiencies, and in consequence, no doubt, of some of them, insects abound. So great, indeed, is the superfœtation of these tribes, that the most unwearying collector will find, all the summer through, abundant employment for his two nets. If the Fauna, immediately around Vichy, must be conceded to be small, her Flora, till recently, was much more copious and interesting; was– since an improved agriculture, here as every where, has rooted out, in its progress, many of the original occupants of the ground, and colonized it with others – training hollyhocks and formal sunflowers to supplant pretty Polygalas and soft Eufrasies; and instructing Ceres so to fill the open country with her standing armies, that Flora, outbearded in the plain, should retire for shelter to the hills, where she now holds her court. Spring sets in early at Vichy; sometimes in the midst of February the surface of the hills is already hoar with almond blossoms. Early in April, anemones and veronicas dapple the greensward; and the willows, deceived by the promise of warm weather, which is not to last, put forth their blossoms prematurely, and a month later put forth their leaves to weep over them. By the time May has arrived, the last rude easterly gale, so prevalent here during the winter months, has swept by, and there is to be no more cold weather; tepid showers vivify the ground, an exuberant botany begins and continues to make daily claims both on your notice and on your memory; and so on till the swallows are gone, till the solitary tree aster has announced October, and till the pale petals of the autumnal colchicum begin to appear; a month after Gouts and Rheumatisms, for which they grow, have left Vichy and are returned to Paris for the winter. We arrived long before this, in the midst of the butterfly month of July. It was warm enough then for a more southern summer, and both insect and vegetable life seemed at their acme. The flowers, even while the scythes were gleaming that were shortly to unfound their several pretensions in that leveller of all distinctions, Hay, made great muster, as if it had been for some horticultural show-day. Amongst then we particularly noticed the purple orchis and the honied daffodil, fly-swarming and bee-beset, and the stately thistle, burnished with many a panting goldfinch, resting momentarily from his butterfly hunt, and clinging timidly to the slender stem that bent under him. Close to the river were an immense number of yellow lilies, who had placed themselves there for the sake, as it seemed, of trying the effect of hydropathy in improving their complexions. But what was most striking to the eye was the appearance of the immense white flowers (whitened sepulchres) of the Datura strammonium, growing high out of the shingles of the river; and on this same Seriphus, outlawed from the more gentle haunts of their innocuous brethren, congregated his associates, the other prisoners, of whom, both from his size and bearing, he is here the chief!

The ContrastWhat a change from the plains of Latium! – a change as imposing in its larger and more characteristic features, as it is curious in its minutest details; and who that has witnessed the return of six summers calling into life the rank verdure of the Colosseum, can fail to contrast these jocund revels of the advancing year in this gay region of France, with the blazing Italian summers, coming forth with no other herald or attendant than the gloomy green of the "hated cypress," and the unrelieved glare of the interminable Campagna? Bright, indeed, was that Italian heaven, and deep beyond all language was its blue; but the spirit of transitory and changeable creatures is quelled and overmastered by this permanent and immutable scene! It is like the contrast between the dappled sky of cheerful morning, when eye and ear are on the alert to catch any transitory gleam and to welcome each distant echo, and the awful immovable stillness of noon, when Pan is sleeping, and will be wroth if he is awakened, when the whole life of nature is still, and we look down shuddering into its unfathomable depth! Standing on the heights of Tusculum, or on the sacred pavement of the Latian Jupiter, every glance we send forth into the objects around us, returns laden with matter to cherish forebodings and despondencies. The ruins speak of an immovable past, the teeming growths which mantle them, the abundant source of future malaria, of a destructive future, and activity, the only spell by which we can evoke the cheerful spirit of the present – activity within us, or around us, there is none. What wonder if we now feel as though the weight of all those grim ruins had been heaved from off the mind, and left it buoyant and eager to greet the present as though we were but the creatures of it! Whatever denizen of the vegetable or the animal kingdom we were familiar with in Italy and miss hereabouts, is replaced by some more cheerful race. What a variety of trees! and how various their shades of green! Though not equal to thy pines, Pamfili, and to thy fair cypresses, Borghese, whose feet lie cushioned in crocuses and anemones, yet a fine tree is the poplar; and yonder, extending for a couple of miles, is an avenue of their stateliest masts. The leaves of those nearest to us are put into a tremulous movement by a breeze too feeble for our skins to feel it; and as the rustling foliage from above gently purrs as instinct with life from within, this peculiar sound comes back to us like a voice we have heard and forgotten. No "marble wilderness" or olive-darkened upland, no dilapidated "Osterie," famine within doors and fever without, here press desolation into the service of the picturesque. Neither here have we those huge masses of arched brickwork, consolidated with Roman cement, pierced by wild fig-trees, crowned with pink valerians or acanthus, and giving issue to companies of those gloomy funeral-paced insects of the Melasome family, (the Avis, the Pimelia, and the Blaps,) whose dress is deep mourning, and whose favoured haunt is the tomb! But in their place, a richly endowed, thickly inhabited plain, filled with cottages and their gardens, farms and their appurtenances, ponds screaming with dog-defying geese, and barnyards commingling all the mixed noises of their live stock together. Encampments of ants dressed out in uniforms quite unlike those worn by the Formicary legions in Italy; gossamer cradles nursing progenies of our Cisalpine caterpillars, and spiders with new arrangements of their eight pairs of eyes, forming new arrangements of meshes, and hunting new flies, are here. Here too, once again, we behold, not without emotion, (for, small as he is, this creature has conjured up to us former scenes and associations of eight years ago,) that tiny light-blue butterfly, that hovers over our ripening corn, and is not known but as a stranger, in the south; also, that minute diamond beetle1 who always plays at bo-peep with you from behind the leaves of his favourite hazel, and the burnished corslet and metallic elytra of the pungent unsavoury gold beetle;2 while we miss the grillus that leaps from hedge to hedge; the thirsty dragon-fly, restless and rustling on his silver wings; the hoarse cicadæ, whose "time-honoured" noise you durst not find fault with, even if you would, and which you come insensibly to like; and that huge long-bodied hornet,3 that angry and terrible disturber of the peace, borne on wings, as it were, of the wind, and darting through space like a meteor!

MiscellaneaThough the "Flora" round about Vichy be, as we have said it is, very rich and various, it attracts no attention. The fat Bœotian cattle that feed upon it, look upon and ruminate with more complacency over it than the ordinary visitors of the place. The only flowers the ladies cultivate an acquaintance with, are those manufactured in Paris; artificial passion flowers, and false "forget-me-nots," which are about as true to nature as they that wear them. Of fruits every body is a judge; and those of a sub-acid kind – the only ones permitted by the doctors to the patients – are in great request. Foremost amongst them, after the month of June, are to be reckoned the dainty fresh-dried fruits from Clermont; of which, again, the prepared pulp of the mealy wild apricot of the district is the best. This pâté d'abricot is justly considered by the French one of the best friandises they have, and is not only sold in every department there, but finds its way to England also. Eaten, as we ate it, fresh from Clermont twice a-week, it is soft and pulpy; but soon becoming candied, loses much of its fruity flavour, and is converted into a sweetmeat.

We should not, in speaking of Vichy to a friend, ever designate it as a comfortable resort for a family; which, according to our English notion of the thing, implies both privacy and detachment. Here you can have neither. You must consider yourself as so much public property, must do what others do —i. e. live in public, and make the best of it. No place can be better off for hotels, and few so ill off for lodgings – the latter are only to be had in small dingy houses opening upon the street. They are, of course, very noisy; nor are the let-ters of them at any pains to induce you by the modesty of their demands to drop a veil over this defect. Defect, quotha! say, rather misery, plague, torture. Can any word be an over-exaggeration for an incessant tintamare, of which dogs, ducks, and drums are the leading instruments, enough to try the most patient ears? The hotels begin to receive candidates for the waters in May; but the season is reputed not to commence till a month later, and ends with September. During this period, many thousand visitors, including some of the ministers of the day; a royal duke; half the Institute; poets, a few; hommes des lettres, many; agents de change, most of all; deputies, wits, and dandies; in fact, all the élite, both of Paris and of the provinces, pay the same sum of seven francs per man, per diem; and, with the exception of the duke, assemble, not to say fraternize, at the same table. But though the guests be not formal, the "Mall," where every body walks, is extremely so. A very broad right-angled intersected by broad staring paths, cut across by others into smaller squares, compels you either to be for ever throwing off at right angles to your course, or to turn out of the enclosure. When the proclamation for the opening of the season has been tamboured through the streets – with the doctors rests the announcement of the day – immediately orders are issued for clean shaving the grass-plats, lopping off redundant branches, to recall the growth of trees to sound orthopedic principles, and to reduce that wilderness of impertinent forms, wherewith nature has disfigured her own productions, into the figures of pure geometry! Hither, into this out-of-doors drawing-room, at the fashionable hour of four P.M., are poured out, from the embouchures of all the hotels, all the inhabitants of them; all the tailor's gentlemen of the Boulevard des Italiens, and all the modisterie of the Tuileries.

Our AmusementsPair by pair, as you see them costumés in the fashions of the month; pinioned arm to arm, but looking different ways; leaning upon polished reeds as light and as expensive as themselves – behold the chivalry of the land! The hand of Barde is discernible in their paletots. The spirit of Staub hovers over those flowery waistcoats; who but Sahoski shall claim the curious felicity of those heels? and Hippolyte has come bodily from Paris on purpose to do their hair. "Un sot trouve toujours un plus sot qui l'admire," says Boileau, and here, in supply exactly equal to the demand, come forth, rustling and bustling to see them, bevies of long-tongued belles, who ever, as they walk and meet their acquaintance, are announcing themselves in swift alternation "charmées," with a blank face, and "toutes desolées," with the best good-will! Here you learn to value a red riband at its "juste prix," which is just what it will fetch per ell; specimens of it in button-holes being as frequent as poppies amidst the corn. Pretending to hide themselves from remark, which they intend but to provoke, here public characters do private theatricals a little à l'écart. Actors gesticulate as they rehearse their parts under the trees. Poets

"Rave and recite, and madden as they stand;"and honourable members read aloud from the Débats that has just arrived, the speech which they spoke yesterday "en Deputés." Our promenade here lacks but a few more Saxon faces amidst the crowd, and a greater latitude of extravagance in some of its costumes, to complete the illusion, and to make you imagine that this public garden, flanked as it is on one side by a street of hotels, and on the opposite by the bank of the Allier, is the Tuilleries with its Sunday population sifted.

Twenty-five francs secures you admission to the "Cercle" or club-house, a large expensive building, which, like most buildings raised to answer a variety of ends, leaves the main one of architectural propriety wholly out of account. But when it is considered how many interests and caprices the architect had to consult, it may be fairly questioned, whether, so hampered, Vitruvius could have done it better; for the ground floor was to be cut up into corridors and bathing cells; while the ladies requested a ball and anteroom; and the gentlemen two "billiards" and a reading-room, with detached snuggeries for smoking —all on the first floor.

Public places, excepting the above-mentioned "Cercle," exist not at Vichy, and as nobody thinks of paying visits save only to the doctor and the springs, "on s'ennui très considerablement à Vichy." If it be true, that, in some of the lighter annoyances of life, fellowship is decidedly preferable to solitude, ennui comes not within the number – every attempt to divide it with one's neighbours only makes it worse; as Charles Lamb has described the concert of silence at a Quakers' meeting, the intensity increases with the number, and every new accession raises the public stock of distress, which again redounds with a surplus to each individual, "chacun en a son part, et tous l'ont tout entier."4 What a chorus of yawns is there; and mutual yawns, you know, are the dialogue of ennui. No wonder; for the physicians don't permit their patients to read any books but novels. They seek to array the "Understanding" against him who wrote so well concerning its laws; Bacon, as intellectual food, they consider difficult of digestion; and even for their own La Place there is no place at Vichy! Every unlucky headache contracted here, is placed to the account of thinking in the bath. If Dr P – suspects any of his patients of thinking, he asks them, like Mrs Malaprop, "what business they have to think?" "Vous êtes venu ici pour prendre les eaux, et pour vous desennuyer, non pas pour penser! Que le Diable emporte la Pensée!" And so he does accordingly!

How we got through the twenty-four hours of each day, is still a problem to us; after making due deductions for the time consumed in eating, drinking, and sleeping. Occasionally we tried to "beat time" by versifying our own and our neighbours' "experiences" of Vichy. But soon finding the "quicquid agunt homines" of those who in fact did nothing, was beyond our powers of description, gave up, as abortive, the attempt to maintain our "suspended animation" on means so artificial and precarious. When little is to be told, few words will suffice. If the word fisherman be derived from fishing, and not from fish, we had a great many such fishermen at Vichy; who, though they could neither scour a worm, nor splice the rod that their clumsiness had broken, nor dub a fly, nor land a fish of a pound weight, if any such had had the mind to try them, were vain enough to beset the banks of the Allier at a very early hour in the morning. As they all fished with "flying lines," in order to escape the fine imposed on those that are shotted, and seemed to prefer standing in their own light – a rare fault in Frenchmen – with their backs to the sun; the reader will readily understand, if he be an angler, what sport they might expect. Against them and their lines, we quote a few lines of our own spinning: —