полная версия

полная версияBelford's Magazine, Vol. II, No. 3, February 1889

Various

Belford's Magazine, Vol. II, No. 3, February 1889 Dec 1888-May 1889

A FEW PRACTICAL FACTS FOR SENATOR EDMUNDS

I am a physician practising in a small manufacturing town, and am doing very well so far as getting business goes – might even be able to save a little money if it were not for the bad debts. They make my income pretty small, considering the amount of hard work I am compelled to do; and the time spent in endeavoring to collect my bills takes a great many hours which, in justice to my patients who pay, ought to be used in brushing up my medical studies and trying to keep abreast with the rest of the profession.

It is hard to get out of a warm bed at night and tramp off a mile or so to look after a patient when you are not certain of ever getting your pay, and it seems to grow worse instead of better. The number of people who, because of their poverty, need a doctor the most are on the increase; and yet so long as they are not poor because of vicious habits, one really hasn't the heart to refuse when called upon. I hear a great deal said about the prosperity of the workingman and the high wages he receives, but observe as a matter of experience that only a few are able to save enough to carry them through a few weeks' illness, let alone paying the doctor, who is forced to wait months and sometimes even years for his pay, getting it then a dollar or two at a time.

To be sure, some of my patients own homes of their own, but the most of them are in debt, a mortgage being about as regular an attachment to a workingman's house as a chimney.

Wages, too, are not quite so high as they were when I began practice: they fell pretty low at one time, and then, when human nature could endure it no longer, came a strike. The employers were horrified; there never had been a strike in this town before: the working men, women, and children all received high wages. "There is John Smith, for instance – earns eighty dollars a month. There is Miss Jones, who makes two dollars a day. There are some who earn even more." True enough! But one day I was called to see John Smith lying dead on his kitchen floor; fell dead on coming home from work, died in the harness, worked to death; a young man at that, and ought to have been good for twenty years more. His employers wouldn't have allowed one of their horses to work that way.

I remember the first time I ever saw Miss Jones – a bright, pretty, red-cheeked girl, fresh from the country and proud to think that she could earn her own living; to-day you would not recognize her, bent, haggard, and worn; the rosy cheeks all gone; and the sunken chest and hollow cough too plainly prophesy the end is not far off. High wages? Yes! for flesh and blood are cheap.

Well, the strikers compromised, got a raise in wages of five per cent., with pay once a month instead of half at the end of the month, and the balance at the end of the year, as had been the custom. Most of the employers gave up the "pluck-me store" system, and we had better times.

Every year there comes family after family, all skilled working men and women, from over the ocean, and I begin to see men standing on the street corners looking for work, while every now and then one of the employers will cut down wages a little in some department of his factory.

I see the men and boys who were born here crowded out of their places by the imported labor, leaving town, and later hear of them beginning life over again in some western village, or taking up government lands on the prairies. If it were not for the emigration out of the town, wages would scarce be enough to support life, so fast does immigration to the town keep up with the demand for labor.

The place used to be full of little shops, and the business was conducted by hundreds of small manufacturers who were but one remove from their men; in fact, it was no uncommon thing for a man to begin manufacturing for himself on the savings from two or three years' labor.

But now these small shops are used as tenements, and a dozen large firms do nearly all the business, crowding the few small manufacturers that are left closer and closer to the wall every year. This is because much of our raw stock has to be imported: we can make only a few kinds of our class of goods in this country. The large manufacturer, who is generally an importer also, is thus able to offer a full line of goods to the jobber, which the smaller fry can't do.

The business is a highly protected industry, the people being taxed by a tariff of fifty per cent to support it.

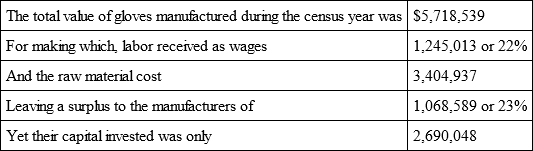

In this connection a few figures may prove instructive:

The tariff of fifty per cent is sufficient therefore to enable the manufacturer to pay, not the difference in wages between European labor and American, but all the wages and twenty-eight cents on the dollar's worth of finished product besides; while – there being no tariff on labor – foreign labor comes to compete with home labor just so fast as the difference in wages will warrant the making of the journey from the old country to the new.

The tariff on gloves in an unfinished state is, however, but twenty per cent, and at that rate many gloves are imported so nearly finished as to require but little labor to fit them for the market: and here the large dealer who imports is able to obtain another serious advantage over the small dealer, and at the same time, while pretending to protect labor, defraud it.

The closing of the small shops, and the consequent driving of our people into large factories, hurts the best skilled workman in that it lessens the number of employers competing for his services. I have been a protectionist in the past, for I was taught to believe that protection raised wages; but the results of a careful inquiry as to cause and effect have shown me pretty conclusively that it does not and can not.

I have talked with many workingmen who are beginning to perceive that the tendency of wages to fall a little from time to time is due to the competition of the "pauper labor of Europe," which coming to this country, underbids them at the shop door, takes away their work, and turns them out to shift for themselves; while the employer, who is protected by a duty of fifty per cent, gets his labor in the lowest market and sells his goods in the highest.

Said a glove-cutter to me the other day: "Doctor, if all the workingmen born and brought up here and all that have come from the old country had remained here, wages would not be fifty cents a day. I understand very well what keeps wages up in America: it's the great West, with its free land acting as a safety valve; and the worst is that so much of it has been given to railroads or sold to cattle syndicates for a mere song. When the remaining free land is appropriated, God help the workingman!

"Yes, we're protected in all that we have to buy: food, clothing, and shelter, in a way that increases the cost to us; but in what we have to sell, our labor, we have no protection at all. They give us good wages, for if they did not we would emigrate to the West and leave them, and by reason of this confounded tariff they put up the price of all we need so high that wages, measured by their purchasing power, are not so large after all. If the difference in real wages was so great as the protectionists claim, there would be more immigrants coming from Europe in one day than do now in a year."

The workingmen have been educating themselves in the last four years, and are no longer to be deceived by superficial comparisons of the differences in wages between countries; they will also examine into the differences in conditions, productive power, and the like, which the protectionist statistician omits to do.

William C. Wood, M. D.IRAR'S PEARL

"One hundred golden pieces for this slave! Who bids? – who bids?"

"One hundred golden pieces? Surely the man has some special talent to be valued so highly."

The speaker stopped, and drew near to the crowd that had gathered about the group of captives crouched in the center of the market-place. As he approached, one among the gathering said:

"Room for the vizier; room, room!"

And the assembled people drew back on either hand, leaving a pathway clear.

The man went forward, followed by his attendants, and faced the inner group of the crowd, a picturesque gathering of armed Bedouins, swarthy and turbaned, clustered about a number of captives whose lighter complexion and free-flowing hair told of a more northern nativity, and which the most ready-tongued of the warriors was now loudly offering for sale.

"One hundred golden pieces buys this slave," he cried again, his eye quickly noticing the interest evinced by the glance of the new-comer; an interest that his ready wit told him might be utilized to advantage.

"And why one hundred golden pieces for this man? Methinks I have seen much stronger knaves sold for an hundred silver pieces; and, lo! you ask for gold. Why?"

"Your servant is a dog if he does not answer the question to the satisfaction of the most exacting. This man comes from the sea that lies beyond our northern mountains, and can live in the water. There is no better diver than he; why, he has brought up pebbles that were ten fathoms down, and surely each fathom's depth is worth ten golden pieces."

The speaker turned to the crowd for approval, and the affirmative nods that greeted his appeal brought a smile of satisfaction to his dark face.

"If you speak truth, you are right," answered the vizier. "But where is your proof?"

"Ask the man; he will not lie."

"Can you do what he claims for you?" questioned the vizier, turning to the captive.

A smile of mingled scorn and contempt passed like a flash across the man's face, and then he said:

"What will it matter to me whether I can or no?"

"This," answered the vizier: "if you can, I shall purchase you for the sultan's pearl fisheries. One pearl each day makes you free for the remaining hours, and the sultan is not a hard master. I have known him give slaves their freedom."

"I need no freedom, for my people are here. Shall I have food and shelter?"

As he spoke his glance swept along the faces of the captives and turned away, a bitter disappointment in it, as though it could not find those for whom it sought.

"You will have food and shelter; yea, and garments for all needs."

"I can do more than he says," said the man.

"Then I will give the golden pieces for him. Bring him to my palace before the sun sets."

And as the man bowed low in answer, the vizier turned and went slowly down the street that led to the sultan's palace.

That evening his new slave lay asleep on a rug in the rose-scented corridor of the palace, and dreamt of freedom and love all through the long hours of the night.

The next day the vizier carried the man to the sultan's divan, and having told of his accomplishments, presented him to his royal master, whose great delight was the vast hoard of pearls that burned like smothered sunbeams in his treasury.

That same day the man was sent to the pearl fisheries on the gulf, and it was ordered that should he prove successful he was to have a house for his special accommodation, and, on his parole of honor, be allowed the freedom of the city and ten leagues of the adjacent country.

Taken to the fisheries, he soon proved himself the master of all engaged in that dangerous work, and was quickly made the favorite of the sultan by the brilliancy and largeness of the pearls that he found. He was given a small house seated in the center of a garden where fruits and flowers commingled in fragrant profusion, and his food and clothing were such as he himself chose, for the orders of his royal master made his wishes in these things law.

His labor for the day was soon over, one pearl, often the result of a five minutes' bath, made him free for the remainder of the twenty-four hours. This time he employed in reading or in taking solitary walks along the shore of the bay opposite to that where the fisheries were located. Here a mass of frowning cliffs rose in dark grandeur against the sky, and over and among these he would clamber for hours, their steep acclivities and the wind-notes that echoed among them seeming to have a strange fascination for him.

At last there came a rumor to the court that the sovereign of a distant Indian realm had become possessed of a pearl whose size and brilliancy of hue were unequalled in the world; and the sultan, hearing of this, sent an envoy to ascertain the truth of the report. The return of this messenger confirmed the statement, and filled the sultan's soul with envy. He knew that he could not purchase the gem, but he determined to stimulate the efforts of his fishers, and for this purpose he caused it to be announced that any slave who should find a pearl more brilliant and larger than that possessed by the Indian monarch should be given his freedom and one hundred thousand pieces of gold.

To Irar, for such was the name by which the northern diver had elected to be known, this proclamation brought no joy. Others of the fishers made desperate exertions to obtain the prize. He brought his daily pearl and went away, basking in the sunlight of his garden, or climbing some rough cliff that he had not scaled before.

When questioned concerning this indifference, he smiled, a scornful and bitter light burning for an instant in his eyes, as he answered:

"Why should I desire to change my life? I have food, a home, clothing; and life can give nothing beyond these. I have no country, no friends. The foray that brought me here swept my people from the face of the earth. My labor is light, my holidays are many. What benefits can freedom give me?"

If the philosophy of his questioner could find no adequate reply to this argument, the passion that slumbered within the slave was not to be so dumb.

He had finished his daily task, and was loitering through a shaded lane just outside of the walls of the city, when he saw approaching the veiled form of a woman. As she came near him, the wind, that kindly agent of man, came blustering down the lane, and before the little brown hands could grasp the filmy white gauze that told of maidenhood, blew it back from the face, and gave Irar a vision that no time nor distance could efface.

He was a strongly-built and handsome fellow, young and brave, just such a man as would please the eyes and heart of a maiden whose love was waiting the call it would so gladly obey; and though a heightened color was hidden by the quickly captured veil, a pleased smile made answer to Irar's look of respectful admiration.

To his salutation, a voice sweet as the nightingale's responded, and then the little form went tripping on, and disappeared through a gateway a short distance from where he stood.

The sunshine of his garden, the conquering of mighty cliffs, ceased to have an attraction for Irar, and his feet seemed drawn to the secluded lane in which this vision had come to him. It was strange how many errands there were calling the little maid along that shaded way; and the wind was ever at hand to give one or more glimpses of the face that was growing sweeter and brighter every day. But while joy was always a portion of these meetings, now and then a dark thought would give its stab; for was he not a slave? And how could he dare to look forward to a time when one so beautiful should be his own? – aye, all and all his own?

He had discovered that were he free he could claim this jewel, for she was a peasant's daughter: and yet how far above him, for she was free.

He had but just left her, having felt the warmth of her breath so near his cheek that it thrilled him like wine, and the clinging clasp of her hand was still tingling in his blood.

"Oh that I could own this pearl!" he cried: and then he shouted aloud in great joyfulness, for the sultan's proclamation flashed up in his mind, recalled by the word he had used.

He would find the sultan a pearl; he would be free – yes, and rich. But his northern blood was cool, and he made sure that his dear one should not suffer should he not succeed at first.

When he met her the next day he said:

"I have come to bid you good-bye for a time."

Her little hand trembled, and her bosom heaved as though a sob were welling up for utterance.

"Only for a time, remember," he went on. "And when I come again it will be to claim a bride."

There was a supreme confidence in his tone, a foreshadowed success that inspired even himself, as he asked:

"Will she be ready for me?"

For answer she nestled in his arms, and no wind was needed to tear the veil aside that his lips might claim love's pledge from hers.

"Shall I have to wait long?" she said.

"No, perhaps a month; but I hope it will be less even than that."

"Oh that Allah would make it less!" she answered.

A long time they lingered in the rose-scented shadows, and then Irar, with her kiss of hope and prayer warm on his lips, strode rapidly back to his home.

Arrived there, he rubbed his body thoroughly with oil to make it mobile and supple, and then sought the slumber that would give him strength for his search.

With the first glinting of dawn he arose, and having partaken of a plain repast, sat down to consider how he should act did he find the pearl.

Should he give the gem to the inspector of the fisheries?

No, for the man was not friendly to him, and might prove false.

The better way would be for himself to carry it to the sultan, and as he laid it at the feet of his royal master, claim the reward that had been offered.

This plan satisfied him, and then another thought arose: How should he hide it from the keen eyes of the watchful guards, whose duty it was to see that no gem was carried away, and who stood ready to search each diver as he appeared above the water?

This was a more difficult problem to settle than was that concerning the way in which the gem should be conveyed to the sultan; and the sun had risen far above the mountains lying eastward from the city before he could devise a plan that seemed to meet his needs.

At last a smile of satisfaction took the place of the perplexed look that had pervaded his face, and rising, he hastened to the bay.

The divers were already at work, and one or two had finished their labor and were going away, when Irar sprang into his skiff and was rowed out to the deeper water, where the pearls lay hidden. He was not so easy to please as he had previously been, but scanned the water curiously, directing the boatmen to pull in many different directions, while he stood in the bow, watching.

Suddenly some mysterious prompting whispered, "Now!" – and without a moment's hesitation he sprang from the skiff and sank swiftly down to the indistinct depths below.

Merciful Allah – did he see aright?

Yes, there lay the pearl he sought, perfect, brilliant, a gem that royalty itself could not outshine.

To grasp it and thrust it into his mouth, yes, and to swallow it, was but an instant's work; and then he quickly found another gem, and with it sped upward to the surface.

A half-hour had not passed, and now he was hastening back to the city, buoyant, elate, his heart beating with swift throbs of joy.

He did not seek his home, but turning down a narrow and unfrequented street sought a dark, closely-curtained house, and knocking, was silently admitted by a sallow-hued man, whose broad brow and gleaming eyes, set deep under shaggy brows, told of a strange and subtle power that only he could wield.

"Well, friend Irar," he said, when he had led the young man to a dim room at the back of the house, "can I do aught for you to-day?"

"You can. Listen." And Irar told, as briefly as he could, of his love, the sultan's promise, and his success.

This done, he went on.

"That you are skilled in the arts of surgery is well known. If the pearl stays in my stomach it will be ruined. For an act that saved your life, which I was glad to do, help me now."

The man thought for a moment, and then said:

"I will, but you will be sick for a week, and perhaps for a longer time. What must be done in this case?"

"Your word will be enough to excuse me from work. Will you not go to the vizier and make the excuse I need?"

"Yes; and now, was the gem hard to swallow?"

"It was."

"Sit quiet here, I shall soon be ready."

Swiftly the man prepared two mixtures and brought out some thin knives and other curious instruments. These and some bandages he placed on a small table that he drew near to a slab standing in the middle of the apartment.

"Lie down here," he said, and Irar obeyed.

"If you feel the pearl forced up into your throat, do not struggle, but grasp the sides of the slab, and keep as quiet as you can: I will see that no harm comes to you."

"I will do as you say."

"Now drink this;" and he handed Irar one of the potions he had prepared.

No sooner had Irar swallowed this than he grew faint and chill; and then a horrible sickness filled him, and with violent retchings he sought to relieve the oppression in his stomach. The man stood by, a knife in his grasp, and just as Irar felt a lump stick in his throat a hand was clasped tightly below it, and it was forced upward. Then a swift movement of gleaming steel followed; and just as the pressure on his lungs grew to a suffocating intensity, the lump causing this was ejected from his throat, and stinging pain told of rapid punctures, through which a thread was quickly drawn.

Then a burning liquid was applied to his throat, and a bandage wound about it, after which he was carried to a couch and told to remain quiet.

Then the man picked up the pearl and, washing it, held it up to the light.

"A right royal gem," he cried, his eyes gleaming. "Here, take it, or I shall begin to envy you your prize;" and he thrust the pearl fiercely into Irar's hand, going immediately from the apartment.

In an hour he returned, holding a paper that bore the seal of the vizier.

"You are excused for a month," he said, "and before that time you will be well: in fact, you will be able to move to your own house in two weeks. The one thing needful is that you keep your neck quiet."

It was not hard for Irar to do this, for did he not know that love and freedom were both waiting for him? The days passed swiftly, for dreams of a happy future filled both waking and sleeping hours, and the contentment that pervaded his existence made his recovery rapid.

At the end of a week the bandages were removed, and the surgeon looked in surprise at the nearly healed cut.

"This is better – much better than I hoped for," he said. "A week more of quiet, and you will be all right."

He bathed the wound with a lotion, replaced the bandages, and then wandered restlessly about the room. This was but a repetition of his course ever since Irar had come to him, and caused his guest no uneasiness.

After a time he grew quiet, and going to the window, seemed to be pondering some plan. Then his face lightened, and coming back to Irar's couch he said:

"I will make a cooling drink for you, and then go out." And he left the room, soon returning with the draught, which he held out to his patient, who took it and drained the liquor to the dregs.

Again the surgeon wandered about the room in a restless way, furtively watching Irar, who soon felt a delicious languor stealing over his senses.

"Let me see your pearl once more," said the surgeon, and Irar languidly handed it to him.

Did he dream it? – or did he see the surgeon clutch it fiercely, then thrust it hurriedly into his mouth and with a gleam of savage triumph hastily swallow it?

There was no certainty of this when he awoke, but a strange sensation of indistinctness in his mind, which gradually cleared as his eyes grew accustomed to the light. But he could not rid himself of the thought, and he thrust his hand under the covering of the couch where he had kept the pearl, and started up with a cry of horror.

The pearl was gone!

A man came running in, alarmed by his cry; and of him Irar demanded, in a voice choked and hoarse with emotion: