полная версия

полная версияAppletons' Popular Science Monthly, November 1898

The story of Government effort toward the establishment of the flax industry need not be told here; there has been widespread prejudice to overcome, with the opposition of the importers, discouragements to be studied and explained, the unvarnished truth to be told, and practical and authoritative information to be given to all who may seek it. The literature of the subject has been disseminated by thousands of copies, and new editions are being ordered.

As to the results: Superior flax has been produced in this country in limited quantities since the work began, and through extended field experiments flax regions have been discovered that are thought to equal the best flax centers of Europe. The department experiments in the Puget Sound region of Washington have demonstrated that we possess in that State a climate and soil that bid fair to rival the celebrated flax region of Courtrai, and from these experiments scutched flax has been produced that is valued by manufacturers in Ireland at three hundred and fifty dollars per ton, and hackled flax worth five hundred dollars per ton. Much has been done, but a great deal more remains to be accomplished in bringing together the farmer and capitalist in the practical work of growing, retting, scutching, and preparing for market American flax fiber, for questions of culture are settled.

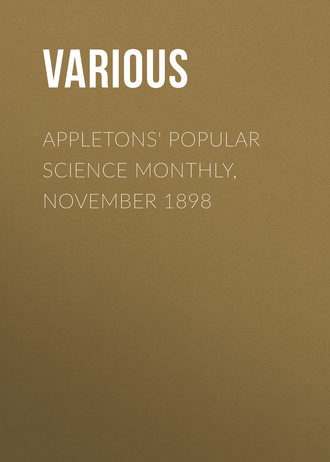

Spreading Hemp in Kentucky.

We should restore our hemp industry to its former proportions by producing high-grade instead of low-grade fiber. The growth of a grade of American hemp that will sell for six to eight cents per pound, instead of three to three and a half cents per pound, as at the present time, means that our farmers must follow more closely the careful practices of Europe, and especially that they must adopt water retting in place of the present practice of dew retting, which gives a fiber dark in color and uneven in quality. A careful consideration of the practices of Italy and France as set forth in Fiber Report No. 11, Department of Agriculture, will materially aid those who desire to change their product from the cheaper dark hemps, for which there is small demand, to the higher-priced light hemps, which will compete with the imported commodity.

One of the most interesting problems of the day in the utilization of the new fiber material, and one that is attracting the attention of all civilized countries, is the industrial production of that wonderful substance known in the Orient as China grass, in India as rhea, and in Europe and America as ramie. The money spent by governments and by private enterprise throughout the world, in experiments and inventions, in the effort to establish the ramie industry, would make up the total of a princely fortune. Obstacle after obstacle has been overcome in the years of persistent effort, and now we stand before the last barrier, baffled for the time, but still hopeful, and with efforts unrelaxed. The difficulty may be stated in a few words: ramie culture will only become a paying industry when an economically successful machine for stripping the fiber has been placed on the market. Hundreds of thousands of dollars have been spent in efforts to perfect a machine, but no Government fiber expert in the world recognizes that we have such a machine at the present time, though great progress has been made in machine construction.

The world's interest in this fiber began in 1869, when a reward of five thousand pounds was offered by the Government of India for the best machine with which to decorticate the green stalks. The first exhibition and trial of machines took place in 1872, resulting in utter failure. The reward was again offered, and in 1879 a second official trial was held, at which ten machines competed, though none filled the requirements, and subsequently the offer was withdrawn. The immediate result was to stimulate invention in many countries, and from 1869 to the present time inventors have been untiring in their efforts to produce a successful machine. The commercial history of ramie, therefore, does not extend further back than 1869.

The first French official trials took place in 1888, followed by the trials of 1889, in Paris, at which the writer was present, and which are recorded in the official reports of the Fiber Investigation series. Another trial was held in 1891, and in the same year the first official trials in America took place, in the State of Vera Cruz, in Mexico, followed the next year by the official trials of American machines in the United States, these being followed by the trials of 1894. Since that year further progress in machine construction has been made, and a third official trial should be held in the near future.

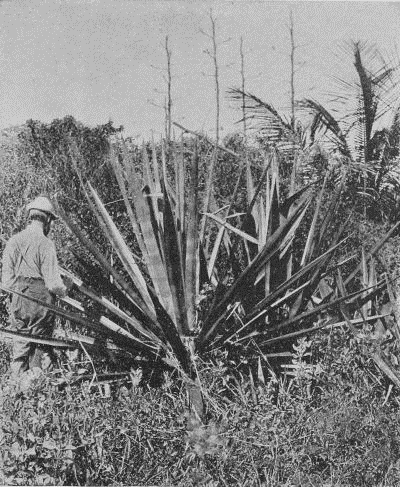

Growth of Jute in Louisiana.

The first records of Chinese shipments of this fiber to European markets show that in 1872 two hundred or three hundred tons of the fiber were sent to London, valued at eighty pounds per ton, or about four hundred dollars. India also sent small shipments, but there was a light demand, with a considerable reduction in price, the quotations being thirty pounds to forty pounds per ton for Chinese and ten pounds to thirty pounds for the Indian product.

Those who are unacquainted with the properties and uses of this wonderful textile may peruse with interest the following paragraph from Fiber Report 7, on the Cultivation of Ramie, issued by the Department of Agriculture:

"The fiber of ramie is strong and durable, is of all fibers least affected by moisture, and from these characteristics must take first rank in value as a textile substance. It has three times the strength of Russian hemp, while its filaments can be separated almost to the fineness of silk. In manufacture it has been spun on various forms of textile machinery, also used in connection with cotton, wool, and silk, and can be employed as a substitute in certain forms of manufacture for all these textiles and for flax also, where elasticity is not essential. It likewise produces superior paper, the fineness and close texture of its pulp making it a most valuable bank-note paper. In England, France, Germany, Austria, and in our own country to an experimental extent, the fiber has also been woven into a great variety of fabrics, covering the widest range of uses, such as lace, lace curtains, handkerchiefs, cloth, or white goods resembling fine linen, dress goods, napkins, table damask, table covers, bedspreads, drapery for curtains or lambrequins, plush, and even carpets and fabrics suitable for clothing. The fiber can be dyed in all desirable shades or colors, some examples having the luster and brilliancy of silk. In China and Japan the fiber is extracted by hand labor; it is not only manufactured into cordage, fish lines, nets, and similar coarse manufactures, but woven into the finest and most beautiful of fabrics."

China is at present the source of supply of the raw product, and the world's demand is only about ten thousand tons, nine tenths of this quantity being absorbed in Oriental countries. The ramie situation in the United States at the present time may be briefly summarized as follows:

The plant can be grown successfully in California and in the Gulf States, and will produce from two to four crops per year without replanting, giving from two hundred and fifty to eight hundred pounds of fiber per acre, dependent upon the number of cuttings, worth perhaps four cents per pound. The machines for preparing this fiber for market are hardly able at the present time to clean the product of one acre (single crop) in a day, and the fiber is quite inferior to the commercial China grass. A new French machine produces a quality of fiber which approaches the China grass of commerce, but its output per day is too small to make its use profitable in this country. All obstacles in chemical treatment of the fiber and in spinning and manufacture are overcome, and the world is waiting for the successful device which will economically prepare the raw material for market.

The part the United States Government is taking in the work is to co-operate in experiments, to issue publications giving all desired information regarding culture, the machine question, and the utilization of the fiber. It tests new decorticators and reports to the public upon their merits or demerits. It cautions farmers and capitalists, for the present, to go into the industry with their eyes open, for the professional promoter has seized upon this industry, above all others in the fiber interest, as one in which he can more readily gull a gullible public. Nevertheless, responsible capitalists are making every legitimate effort to place the manufacturing industry on a solid basis in this country, and to attain to the progress made in other countries where manufacture has already been established, and where the Chinese fiber is employed as the raw material.

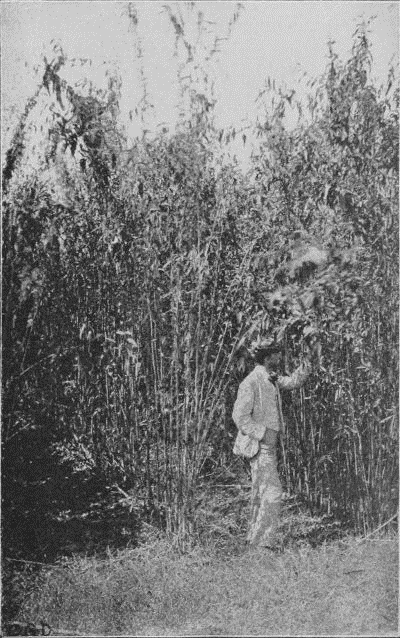

A Florida Sisal Hemp Plant.

Thus far I have only considered spinning fibers. More than one half of the raw fibers imported in the United States are employed in the manufacture of rope and small twine, or bagging for baling the cotton crop. Cordage is manufactured chiefly from the Manila and Sisal hemps, the former derived from the Philippine Islands, the latter from Yucatan. Some jute is also used in this industry, though the fiber is more largely employed in bagging; and some common hemp, such as is grown in Kentucky, is also used.

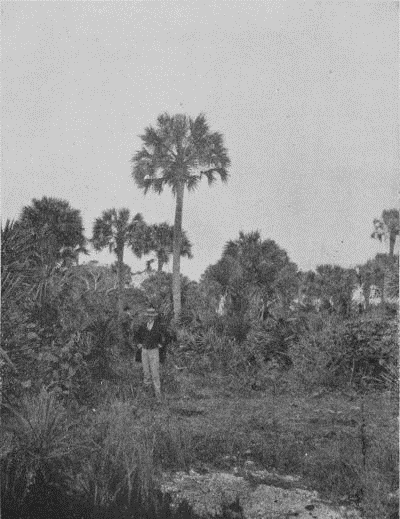

We can not produce Manila hemp in the United States, and this substance will always hold its own for marine cordage. Jute will grow to perfection in many of the Southern States, but it is doubtful if we can produce it at a price low enough to compete with the cheaper grades of the imported India fiber. Rough flax and common hemp might be used in lieu of jute, in bagging manufacture, but the question of competition is still a factor. Sisal hemp, which has been imported to the value of seven million dollars a year, when prices were high, will grow in southern Florida, and the plant has been the subject of exhaustive study and experiment. This plant was first grown in the United States on Indian Key, Florida, about 1836, a few plants having been introduced from Mexico by Dr. Henry Perrine, and from this early attempt at cultivation the species has spread over southern Florida, the remains of former small experimental tracts being found at many points, though uncared for.

Pineapple Field in Florida.

The high prices of cordage fibers in 1890 and 1891, brought about by the schemes of certain cordage concerns, called attention to the necessity of producing, if possible, a portion of the supply of these hard fibers within our own borders. In 1891, in response to requests for definite information regarding the growth of the Sisal hemp plant, a preliminary survey of the Key system and Biscayne Bay region of southern Florida was made by the Department of Agriculture, and in the following year an experimental factory was established at Cocoanut Grove with special machinery sent down for the work. With this equipment, and with a fast-sailing yacht at the disposal of the special agent in charge of the experiments, a careful study of the Sisal hemp plant, its fiber, and the possibility of the industry was made, and the results were duly published. About this time the Bahaman Government became interested in the industry, and with shiploads of plants, both purchased and gathered without cost on the uninhabited Florida Keys, the Bahamans began the new industry by setting out extensive plantations on the different islands of the group. The high prices of 1890 having overstimulated production in Yucatan, two or three years later there was a tremendous fall in the market price of Sisal hemp, and Florida's interest in the new fiber subsided, though small plantations had been attempted. In the meantime, American invention having continued its efforts in the construction of cleaning devices, two successful machines for preparing the raw fiber have been produced which have, in a measure, superseded the clumsy raspadore hitherto universally employed for the purpose, and one of the obstacles to the production of the fiber in Florida is removed. The reaction toward better prices has already begun, and the future establishment of an American Sisal hemp industry in southern Florida is a possibility, though there are several practical questions yet to be settled.

Pineapple culture is already a flourishing industry in the Sisal hemp region. A pineapple plant matures but one apple in a season, and after the harvest of fruit the old leaves are of no further use to the plant, and may be removed. The leaves have the same structural system as the agaves – that is, they are composed of a cellular mass through which the fibers extend, and when the epidermis and pulpy matter are eliminated the residue is a soft, silklike filament, the value of which has long been recognized. Only fifty pounds of this fiber can be obtained from a ton of leaves, but, as the product would doubtless command double the price of Sisal hemp, its production would be profitable. How to secure this fiber cheaply is the problem. The Sisal hemp machines are too rough in action for so fine a fiber, and, at the rate of ten leaves to the pound, working up a ton of the material would mean the handling of over twenty thousand leaves to secure perhaps three dollars' worth of the commercial product. Were the fiber utilized in the arts, however, and its place established, it would compete in a measure with flax as a spinning fiber, for its filaments are divisible to the ten-thousandth of an inch. The substance has already been utilized to a slight extent in Eastern countries (being hand-prepared) in the manufacture of costly, filmy, cobweblike fabrics that will almost float in air.

Another possible fiber industry for Florida is the cultivation of bowstring hemp, or the fiber of a species of Sansevieria that grows in rank luxuriance throughout the subtropical region of the State. The fiber is finer and softer than Sisal hemp, though not so fine as pineapple fiber, and would command in price a figure between the two. The yield is about sixty pounds to the ton of leaves. Many other textile plants might be named that have been experimented with by the Government or through private enterprise, but the most important, in a commercial sense, have been named.

A Plant of New Zealand Flax.

There is a considerable list of plants, however, which are the subject of frequent inquiry, but which will never be utilized commercially as long as other more useful fibers hold the market. These for the most part produce bast fiber, and the farmer knows them as wild field growths or weeds. They are interesting in themselves, and many of them produce a fair quality of fiber, but to what extent they might be brought into cultivation, or how economically the raw material might be prepared, are questions the details of which only experiment can determine. But the fact that at best they can only be regarded as the substitutes for better, already established, commercial fibers has prevented serious experiment to ascertain their place. They are continually brought to notice, however, for again and again the thrifty farmer, as he finds their bleached and weather-beaten filaments clinging to the dead stalks in the fields, deludes himself in believing that he has made a discovery which may lead to untold wealth, and a letter and the specimen are promptly dispatched to the fiber expert for information concerning them. In such cases all that can be done is to give full information, taking care to let the inquirer down as easily as possible.

The limit of practical work in the direction of new textile industries is so clearly defined that the expert need never be in doubt regarding the economic value of any fiber plant that may be submitted to him for an opinion, and the long catalogue of mere fibrous substances will never demand his serious attention.

In studying the problem of the establishment of new fiber industries, therefore, we should consider "materials" rather than particular species of plants – utility or adaptation rather than acclimatization. We should study the entire range of textile manufacture, and before giving attention to questions of cultivation we should first ascertain how far the plants which we already know can be produced within our own borders may be depended upon to supply the "material" adapted to present demands in manufacture. If the larger part of our better fabrics – cordage and fine twines, bagging, and similar rough goods – can be made from cotton, flax, common hemp, and Sisal hemp, which we ought to be able to produce in quantity at home, there is no further need of costly experiments with other fibers. Unfortunately, however, it is possible for manufacturers to "discriminate" against a particular fiber when the use of another fiber better subserves their private interests. As an example, common hemp was discriminated against in a certain form of small cordage, in extensive use, because by employing other, imported fibers, it has been possible in the past to control the supply, and in this day of trusts such control is an important factor in regulating the profits. With common hemp grown on a thousand American farms in 1890, the price of Sisal and Manila hemp binding twine, of which fifty thousand tons were used, would never have been forced up to sixteen and twenty cents a pound, when common hemp, which is just as good for the purpose, could have been produced in unlimited quantity for three and a half cents. The bagging with which the cotton crop is baled is made of imported jute, but common hemp or even low-grade flax would make better bagging. A change from jute to hemp or flax in the manufacture of bagging (it would only be a return to these fibers), could it be brought about, would mean an advantage of at least three million dollars to our farmers. Yet in considering such a desirable change we are confronted with two questions: Is it possible to compete with foreign jute? and can prejudice be overcome? For it is true that there are, even among farmers, those who would hesitate to buy hemp bagging at the same price as jute bagging because it was not the thing they were familiar with. But some of them will buy inferior jute twine, colored to resemble hemp, at the price of hemp, and never question the fraud.

Cabbage Palmetto in Florida.

Our farmers waste the fibrous straw produced on the million acres of flax grown for seed. It has little value, it is true, for the production of good spinning flax, yet by modifying present methods of culture, salable fiber can be produced and the seed saved as well, giving two paying crops from the same harvest where now the flaxseed grower secures but one.

In summarizing the situation in this country, therefore, it will be seen that, out of the hundreds of fibrous plants known to the botanist and to the fiber expert, the textile economist need only consider four or five species and their varieties, all of them supplying well-known commercial products that are regularly quoted in the world's market price current, the cultivation and preparation of which are known quantities. Were the future of new fiber industries in this country to rest upon this simple statement, there would be little need of further effort. The problem, however, is one of economical adaptation to conditions not widely understood in the first place, and not altogether within control in the second.

Twenty flax farmers in a community decide to grow flax for fiber, and two of these farmers are perhaps acquainted with the culture. They go to work each in his own way; ten make a positive failure in cultivation for lack of proper direction, five of the remaining ten fail in retting the straw, and five succeed in turning out as many different grades of flax line, only one grade of which may come up to the standard required by the spinners. And all of them will have lost money. If the failure is investigated it will be discovered that the proper seed was not used; in some instances the soil was not adapted to the culture, and old-fashioned ideas prevailed in the practice followed. The straw was not pulled at the proper time, and it was improperly retted. The breaking and scutching were accomplished in a primitive way, because the farmers could not afford to purchase the necessary machinery, and of course they all lost money, and decided in future to let flax alone.

But the next year the president of the local bank, the secretary of the town board of trade, and three or four prosperous merchants formed a little company and built a flax mill. A competent superintendent – perhaps an old country flax-man – was employed, a quantity of good seed was imported, and the company contracted with these twenty farmers to grow five, ten, or fifteen acres of flax straw each, under the direction of the old Scotch superintendent. The seed was sold to them to be paid for in product; they were advised regarding proper soil and the best practice to follow; they grew good straw, and when it was ready to harvest the company took it off their hands at a stipulated price per ton. The superintendent of the mill assumed all further responsibility, attended to the retting, and worked up the product. Result: several carloads of salable flax fiber shipped to the Eastern market in the winter, the twenty farmers had "money to burn" instead of flax straw, and the company was able to declare a dividend. This is not altogether a supposititious case, and it illustrates the point that in this day of specialties the fiber industry can only be established by co-operation.

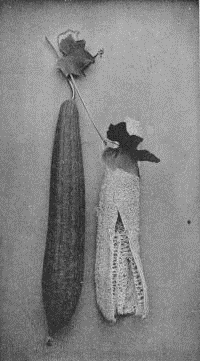

The Luffa, or Sponge Cucumber.

In all these industries, whether the fiber cultivated is flax, ramie, or jute, the machine question enters so largely into the problem of their successful establishment that the business must be conducted on a large scale. Even in the growth of Sisal hemp in Florida, should it be attempted, the enterprise will only pay when the necessary mill plant for extracting the fiber is able to draw upon a cultivated area of five hundred acres. In other words, the small farmer can never become a fiber producer independently, but must represent a single wheel in the combination.

The subject is a vast one, and, while I have been able to set forth the importance of these industries as new sources of national prosperity, only an outline has been given of the difficulties which are factors in the industrial problem. Summing up the points of vantage, the market is already assured; through years of study and experiment we are beginning to better understand the particular conditions that influence success or failure in this country; we have the best agricultural implements in the world, and American inventive genius will be able, doubtless, in time, to perfect the new mechanical devices which are so essential to economical production; our farmers are intelligent and industrious, and need only the promise of a fair return for their labor to enter heart and soul into this work.

WHAT IS SOCIAL EVOLUTION?

By HERBERT SPENCERThough to Mr. Mallock the matter will doubtless seem otherwise, to most it will seem that he is not prudent in returning to the question he has raised; since the result must be to show again how unwarranted is the interpretation he has given of my views. Let me dispose of the personal question before passing to the impersonal one.

He says that I, declining to take any notice of those other passages which he has quoted from me, treat his criticism as though it were "founded exclusively on the particular passage which" I deal with, "or at all events to rest on that passage as its principal foundation and justification."[4] It would be a sufficient reply that in a letter to a newspaper numerous extracts are inadmissible; but there is the further reply that I had his own warrant for regarding the passage in question as conclusively showing the truth of his representations. He writes: —