полная версия

полная версияAppletons' Popular Science Monthly, April 1899

Yet under a craze for centrifugal expansion we are now in danger of trying to develop tropical islands far away, already somewhat densely peopled, where white men can not work and live, to our detriment, danger, and loss, while we fail to see that if we expand centripetally by the occupation and use of the most healthy and productive section of our own country, we may add immensely to our prosperity, our wealth, to our profit without cost and without militarism. This sparsely settled Land of the Sky is greater in area and far greater in its potential than the Philippine Islands, Cuba, and Porto Rico combined. Verily, it seems as if common sense were a latent and sluggish force, often endangered by the noisy and blatant influence of the venal politician and the greed of the unscrupulous advocates of vassal colonies who now attempt to pervert the power of government to their own purposes of private gain.

Witness the blunders of the past:

We nearly gave away Oregon because it was held not to be worth retaining.

When the northern boundary of Wisconsin was being determined, it was put as far north as it was then supposed profitable farming could ever extend, excluding Minnesota, now one of our greatest sources of wheat.

The Great American Desert in my own school atlas covered a large part of the most fertile land now under cultivation.

What blunders are we now making for lack of "speculation" or "intellectual examination" as to the future of American farming and farm lands?

On one point to which Mr. Hyde refers I must cry peccavi. He rebukes the editor of the Popular Science Monthly for admitting an article in which a potential of 400,000,000 bushels of wheat is attributed to the State of Idaho. The total depravity of the type-writing machine caused the mechanism to spell Montana in the letters I-d-a-h-o. What I imputed to Idaho is true of Montana, if the Chief of the Agricultural Experiment Stations of Montana is a competent witness, if all its arable land were devoted to wheat. It will be observed that I mentioned Idaho incidentally (meaning Montana), taking no cognizance of the estimate given, because it was at present of no practical importance.

I have expressed my distrust of great averages in respect to agriculture and farm products.

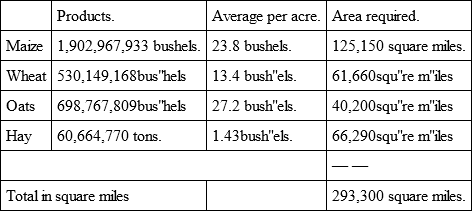

In illustration of this fallacy, the figures presented by Mr. Hyde will now be dealt with. It is held that in 1930, which is the year when Sir William Crookes predicts starvation among the bread-eating people of the world for lack of wheat (as if good bread could only be made from wheat), the population of this country may be computed at 130,000,000. The requirements of that year for our own consumption Mr. Hyde estimates at 700,000,000 bushels of wheat, 1,250,000,000 bushels of oats, 3,450,000,000 bushels of corn (maize), and 100,000,000 tons of hay; and, although other products are not named by him, we may assume a corresponding increase.

Subsequently Mr. Hyde gives the present delusive average yields per acre of the whole country, and then throws a doubt on the future progress of agricultural science, saying, "Whatever agricultural science may be able to do in the next thirty years, up to the present time it has only succeeded in arresting that decline in the rate of production with which we have been continually threatened." Without dealing at present with this want of and true consideration of or "speculation" upon the progress made in the last decade under the lead of the experiment stations and other beginnings in remedying the wasteful and squalid methods that have been so conspicuous in pioneer farming, let us take Mr. Hyde's averages and see what demand upon land the requirements of 1930 will make, even at the present meager average product per acre.

Mr. Hyde apparently computes this prospective product as one that will be required for the domestic consumption of 130,000,000 people by ratio to our present product. He ignores the fact that our present product suffices for 75,000,000, with an excess of live stock, provisions, and dairy products exported nearly equal in value to all the grain exported, and in excess of the exports of wheat. If we can increase proportionally in one class of products, why not in another? Whichever pays best will be produced and exported.

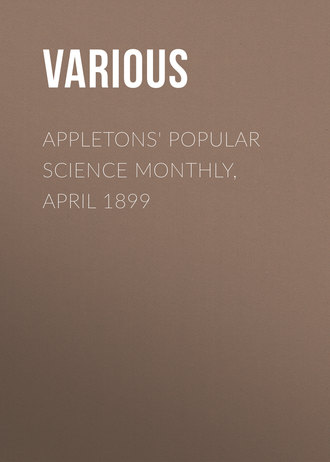

1897 and 1930 compared. – Data of 1897.

All other farm crops carry the total to less than 400,000 square miles now under the plow, probably not exceeding 360,000.

Prospective demand of 1930, at the same meager average product per acre, without progress in agricultural science:

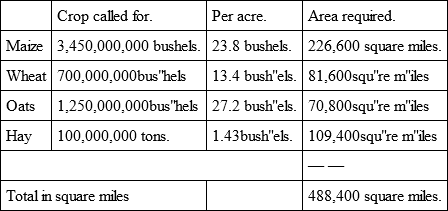

Assuming all land under the plow in 1930 in the ratio as above, the area of all now in all crops 400,000 square miles – an excessive estimate – that year (1930) will call for 667,000 square miles of arable land in actual cultivation.

I have been accustomed to consider one half our national domain, exclusive of Alaska, good arable land in the absence of any "speculation" on that point in the records of the Department of Agriculture; but from the returns given by the chiefs of the experiment stations and secretaries of agriculture of the States hereafter cited, that estimate may be increased probably to two thirds, or 2,000,000 square miles of arable land out of a total of 3,000,000 square miles, omitting Alaska.

Assuming that we possess 2,000,000 square miles of arable land, capable at least of producing the present meager average product cited above, the conditions of 1930 will be graphically presented on the following diagram:

Prospective Use of Land in the Year 1930 on Present Crop Average.

(Arable land assumed to be 2,000,000 square miles in the outer lines of the diagram)

No reduction on area cultivated on prospective improvement in the present methods of farming, although it may be assumed that the prospective increase of crop per acre will exert great influence.

If the facts should be in 1930 consistent with Mr. Hyde's "speculation" it would therefore appear that our ability to meet the domestic demand of 1930 with proportionate export of cattle, provisions, and dairy products, and to set apart a little patch of land for the export of 1,226,000,000 bushels of wheat raised at the rate of only 13.4 bushels per acre from 143,000 square miles of land will be met by the cultivation of not exceeding 700,000 square miles out of 2,000,000 available.

I should not venture to question the conclusions emanating from the Department of Agriculture, or the deductions of so eminent a scientist as Sir William Crookes, had I not taken the usual precaution of a business man in studying a business question. I went to the men who know the subject as well as the figures on which statistics are to be compiled.

Being supplied by the Popular Science Monthly with one hundred proofs of the first nine and a half pages of the December article in which the terms of the problem are stated, I sent those proofs to the chiefs of the experiment stations and to the secretaries of agriculture in all the States from which any considerable product of wheat is now or may be hereafter derived; also to many makers of wheat harvesters; to the secretaries of Chambers of Commerce, and to several economic students in the wheat-growing States. This preliminary study was accompanied by the following circular of inquiry:

Boston, Mass., October 5, 1898.To the Chiefs of the Agricultural Experiment Stations and others in Authority:

Calling your attention to the inclosed advance sheets of an article which will by and by appear in the Popular Science Monthly, I beg to put to you certain questions.

If the matter interests you, will you kindly fill up the blanks below and let me have your replies within the present month of October, to the end that I may compile them and give a digest of the results? I shall state in the article that I am indebted to you and others for the information submitted.

Area of the State of........... square miles.

1. What proportion of this area do you believe to be arable land of fair quality, including pasture that might be put under the plow?

Answer ......... square miles.

2. What proportion is now in forest or mountain sections which may not be available for agriculture for a long period?

Answer ......... square miles.

3. What has been done or may be done by irrigation?

.............................. .............................. ..............................

4. What proportion of the arable land above measured should you consider suitable to the production of wheat under general conditions such as are given in the text, say, a stable price of one dollar per bushel in London?

Answer ......... square miles.

5. To what extent, in your judgment, is wheat becoming the cash or surplus crop of a varied system of agriculture as distinct from the methods which prevail in the opening of new lands of cropping with wheat for a term of years?

.............................. .............................. ..............................

What further remarks can you add which will enable me to elucidate this case, to complete the article and to convey a true impression of the facts to English readers?

.............................. .............................. ..............................

Your assistance in this matter will be gratefully received.

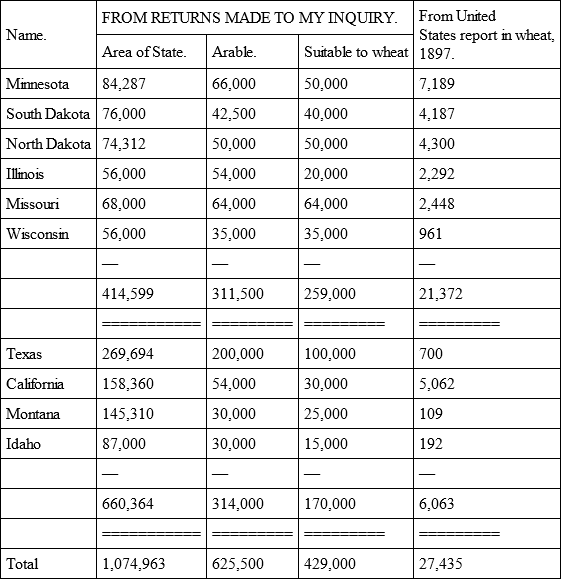

Respectfully submitted,Edward Atkinson.To this circular I received twenty-four detailed replies, containing statistics mostly very complete; also many suggestive letters, in every case giving full support to the general views which I had submitted in the proof sheets. It has been impossible for me to give individual credit within the limits of a magazine article to the gentlemen who have so fully supplied the data. Space will only permit me to submit a digest of the more important facts in a table derived from these replies:

I do not give the data of the Eastern and Southern States, and I have selected only the most complete data of the other States, choosing the more conservative where two returns have been made from one State.

The foregoing States produced a little over one third of the wheat crop of 1897. They comprise a little over one third the area of the land of the United States, excluding Alaska.

The list covers States like Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, now very fully occupied relatively to Texas, Montana, and Idaho, as yet but sparsely settled.

Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Oregon, and Washington combined far exceed the above list in wheat production; but, as I have no complete data from these States, I can only say that the national or census statistics, as far as they go, develop corresponding conditions to those above given. The very small product of Texas and Montana, even of Idaho, as compared with the claimed potential, will attract notice, and perhaps excite incredulity. But let it be remembered that in 1880 the Territory of Dakota yielded less than 3,000,000 bushels of wheat, while in 1898 the two States of North and South Dakota, formerly in one Territory, claim to have produced 100,000,000 bushels. Perhaps it will then be admitted that the potential of Montana, and even of Idaho, may be attained in some measure corresponding to the reports from those States; but as yet their product is a negligible quantity, as that of Dakota was only twenty years since.9

Again, let it be remembered that Texas will produce a cotton crop, marketed in 1898-'99, above the average of the five ante-war crops of the whole country, and nearly equal to the largest crop ever grown in the United States before the war. Texas could not only produce the present entire cotton crop of the United States but of the world, on but a small part of her land which is well suited to cotton. When these facts are considered, perhaps the potential of that great State in wheat and other grain, in cattle and in sheep, as well as in cotton, may begin to be comprehended.

The writer is well aware that this treatment of a great problem is very incomplete, but it is the best that the leisure hours of a very busy business life would permit. If it discloses the general ignorance of our resources, the total inadequacy of many of our official statistics, the lack of any real agricultural survey, and the necessity for a reorganization and concentration of the scientific departments of the Government as well as of a permanent census bureau, it will have served a useful purpose.

If it also serves to call attention to the meager average crops and the poor quality of our agriculture as a whole down to a very recent period, it may suggest even to those to whose minds the statistics of the past convey but gloomy and "doubtful views" of the future, that the true progress in scientific agriculture could only begin when substantially all the fertile land in the possession of the Government had either been given away or otherwise distributed. So long as "sod crops" and the single-crop system yielded adequate returns to unskilled farmers, no true science of agriculture could be expected, any more than a large product of wool can be hoped for in States where it has been wittily said that "every poor man keeps one cur dog, and every d – d poor man keeps two or more."

Finally, if I shall have drawn attention to the very effective work which is being done in the agricultural experiment stations by men of first-rate ability, I shall have drawn attention to a great fact. This work has already led to a complete revolution from the old practice of maltreating land, and to the renovation of soils that had been partially exhausted. Governor Henry A. Wise, of Virginia, long since condemned the old methods of Southern agriculture by telling his hearers, "The niggers skinned the land and the white men skinned the niggers." We are changing all that by new and progressive methods. I hope that in this recognition of the work of the experiment stations I shall have made some return for the attention which has been given to my inquiry by so many of my correspondents that the space assigned me forbids a list of my authorities being given by name.

When the suggestion is made from the Department of Agriculture that all that science has yet accomplished has been to stop a tendency to a lessened production from the land now under the plow, and when it is even suggested that in 1930 the present meager average of crops per acre may still exist, it seems to me that little credit is given to the good work already accomplished in the short period in which the separate Department of Agriculture has been represented in the Cabinet, especially in the last five or six years, while the suggestion itself shows very little consideration of the great work of the experiment stations.

Unless it can be proved that my correspondents and myself have entered into a conspiracy to mislead the public in dealing with the potential of this country in wheat production, nearly all the deductions from the figures of the past must be considered mere statistical rubbish. These statistics cover sections and States in which wheat should never be grown or attempted in competition with the true wheat soils and climate. As well might misplaced iron furnaces, built to boom city lots where there are no favorable conditions for the production of iron, be included in an average and held up as a standard of our potential in iron and steel production.

In my efforts to discover the rule of progress in the arts and occupations of the people of this country, it has become plain that in ratio to the application of science and invention to every art the quantity of product is increased, the number of workmen is relatively diminished, the price of the product tends to diminish, while the wages or earnings of those who do the work are augmented. I have investigated many branches of industry, and find evidence conclusive to my own mind that such is the law of industrial development. This rule is subject to temporary variations under the restriction of statutes. In my own judgment, the so-called protective principle or policy of interference with commerce by imposing fines on foreign imports has retarded the progress of the specially protected arts, and has in some measure obstructed the diversity of manufactures; but the opposite policy of absolutely free trade in our domestic traffic over a greater area and among a much larger number of people than have elsewhere secured their own liberty has been so much more potent in its progressive influence as to have lessened the evils of the restrictions on foreign trade.

According to my observation, all the efforts to regulate railroad charges by State legislation and under the interstate commerce act have greatly retarded the progress of the railway, and have deprived great States, notably Texas, of any service at all commensurate to the demand which might otherwise have been supplied to the mutual benefit of the owners of the railways and the inhabitants of the State. The most serious retarding influence, especially evil in its effect upon farmers, was the useless panic of 1893, caused by the silver craze – that is to say, by the effort to enact a force bill by which the producers of our great crops would have been compelled to accept money of half the purchasing power of that to which their industry had been long adjusted. This caused a temporary paralysis of industry, in which I think none suffered so much as the farmers of the country.

But admitting these temporary variations, I find the same rule governing the products of the farm that governs the mine, the factory, and the workshop – namely, a lessening of the number occupied in ratio to the product; a great reduction in the cost of labor; an increased return in due proportion of the skill and intelligence of the farmer; a rapid reduction in the farm mortgages, ending at the present date in making the farmers of the grain-growing States the creditors of the world, especially those occupied upon wheat.

But in the development of this progress we find the reverse of the practice in the factory and the workshop. The most important applications of science and invention led first to what might be called the manufacture of wheat on an extensive method of making a single crop on great areas of land. That phase has about spent its force; the great farms are in process of division; the single-crop system has about ended; the intensive system of making a larger product from a lessened area with alternation and variation in crops is rapidly taking the place of former methods.

Therefore, while many branches of manufacturing tend more and more to the collective method, the tendency in agriculture is more and more to individualism in dealing with the land itself, coupled with collective ownership in the more expensive farm machinery, in creameries, cheese factories, and the like. We are apparently at a halfway stage in this revolution of agriculture. The intelligent and intensive methods of breeding cattle and sheep is also rapidly taking the place of the semibarbarous conditions of the ranch.

If these points are well taken, the very suggestion that we must compute the land which should be under the plow in 1890 in order to supply the needs of 130,000,000 people on the basis of the imperfect statistics and inadequate data of the past, becomes almost an impertinence. It is much more probable that the 400,000 square miles which now meet the needs of 75,000,000 people, with an enormous excess for export, will in 1930 still suffice for the domestic supply of 130,000,000 people, with a proportionate export corresponding to the present.

If the product of the farms of the West now yielding the largest crops, or of the renovated lands of the South now yielding the best crops, be taken as the average standard of the near future, as they should be, then it may be true in 1930, as it is now, that one fifth of the arable land of this country when put under the plow will still suffice for all existing demands, the remainder of our great domain extending the promise of future abundance and welfare to the yet greater numbers who will occupy the land a century hence.

I may add that in the course of a very friendly correspondence with Sir William Crookes, while we are still at variance in our estimates of the area which may be converted to the production of wheat in this country without trenching upon any other product, we are wholly at an agreement on a most material point. I quote from one of his letters: "Under the present wasteful method of cultivation there will be in a limited number of years an insufficient supply of wheat. Apply artificial fertilizers judiciously, and the supply may be increased indefinitely." I would only venture to add to the judgment of so eminent a writer the words "or natural," to the end that the paragraph should read, "Apply artificial or natural fertilizers judiciously, and the supply can be increased indefinitely."

Many years ago I was asked among others, "What would be the next great discovery of science or invention?" To which I replied, "A supply of nitrogen at low cost." Has not that discovery been made in the recent development of the functions of the bacteria which, living and dying upon the leguminous plants, dissociate the nitrogen of the atmosphere and convert it through the plant to the renovation of the soil? Is not the invention of methods of nitrifying the soil by distributing the germs of bacteria one of the most wonderful discoveries of science ever yet attained? Can any one yet measure the potential of any given area of land in any part of this country in the production of any one of its great crops? That there is a limit may be admitted. Can any one venture to say that any of our average crops yet approach beyond a small fractional measure the true limit of production, whatever it may be, either in cotton, maize, wheat, or any other product of the soil?

In this, as in many other developments of the theory of evolution, the factor of mental energy, which is the prime factor in all material production, may have been or is almost wholly ignored. We are ceasing to treat the soil as a mine subject to exhaustion, but we have as yet made only a beginning in treating it as an instrument of production which will for a long period respond in its increasing product in exact ratio to the mental energy which is applied to the cultivation of the land.

THE COMING OF THE CATBIRD

By SPENCER TROTTERIn southeastern Pennsylvania there comes a day in February that brings with it an indefinable sense of joyousness. A southerly wind wanders up the Delaware with a touch of the spring in its air that quickens, for the first time, the slumbering life. It is then that those mysterious forces in the cells of living things begin their subtle work – hidden in the dark, underground storehouses of plants and the sluggish tissues of animals buried in their winter sleep. On such a day the ground hog ventures from his burrow, some restless bee is lured from the hive to wander disconsolate over bare fields, a snake crawls from its hole to bask awhile in the sunshine, and one looks instinctively for the first breaking of the earth that tells of the early crocus and the peeping forth of daffodils. The southerly wind is more apt than not to be a telltale, for with all its springtime softness it is drawing toward some storm center, near or remote, that will inevitably follow with rough weather in its sweep. The country folk rightly call such a day a "weather breeder," and even the ground hog knows its portent in the very sign of his shadow. Come as it will, the day is really a day borrowed in advance from the spring, as though to hearten one through all the dreary days that will follow and, in starting the growing forces of vegetation, to make ready for the season's coming.

With this forerunner of the year come the harbingers of the bird migration. With the rise of the temperature to sixty or over, a well-marked bird wave from the south spreads over the Delaware Valley. On this balmy, springlike day we hear for the first time since November the croaking of grackles as a loose flock wings overhead or scatters among the tree tops. A few robins may show themselves, and the mellow piping of bluebirds lends its sweet influence to the charm of such a day. There is a sense of uncertain whereabouts in the bluebird's note, a sort of hazy, in-the-air feeling that suggests sky space. It does not seem to have the tangible element by which we can locate the bird as in the voices of the robin and the song sparrow. It is on such a day as this that song sparrows are first heard – cheery ditties from the weather-beaten fences and the bare, brown tangle of brier patches. The day may close lurid with the frayed streamers of lofty cirrus clouds streaking across the sky – the vaporous overflow of a coming storm – or a week of the same bright weather may continue with the wind all the while blowing softly out of the south, but sooner or later the inevitable winter storm must close this foretaste of the spring.