Полная версия

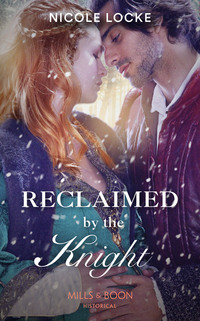

The Knight's Broken Promise

‘Artless and bootless.’ She angrily picked up each branch and leaf and tucked them into the crook of her arm. ‘That’s what you are. In more ways than one.’

She slid backwards until the slope became flat and then she whirled around. Robert stood a hand’s breadth from her. Startled, she stumbled, branches flew, and her body slid against his.

Her world was instantly, aggressively, the smell of hot male and cedar and the feel of sweat-covered skin. Her fingers clawed down the shoulder muscles she’d stared at all day. Her breasts burned…her legs tangled. She teetered and pressed harder for support.

Robert inhaled sharply, as if he’d been dropped into an icy lake. He ripped himself away.

AUTHOR NOTE

There are times in your life when you think you’re going to have one experience and you have a completely different one. This is what happened to me when I toured castles in Wales.

Now, I knew I’d be excited and awed, and that my imagination would run wild. They are castles, after all. What I didn’t plan on was the unerring sense of story, of the people who lived during that time. I didn’t have to close my eyes and pretend, and I didn’t have to squint to force my eyes to see. They were all simply there.

Robert, an English knight, was there. Hunched and grieving under a tree. His broad back and bared arms were a testament to the times and to his training—and to a man used to war. But his grief came from something else…from loss, from hope forsaken.

I could do nothing for him. But I knew he couldn’t stay where he was and I knew there had to be someone for him.

And there is someone…in Scotland…in 1296…on the cusp of the greatest conflict. But Gaira of Clan Colquhoun laughs at conflict—in fact she curses at it all the time. And when she meets Robert she curses at him, too.

The Knight’s Broken Promise

Nicole Locke

NICOLE LOCKE discovered her first romance novels in her grandmother’s closet, where they were secretly hidden. Convinced that books hidden must be better than those that weren’t, Nicole greedily read them. It was only natural for her to start writing them (but now not so secretly). She lives in London with her two children and her husband—her happily-ever-after.

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

SIGN ME UP!

Or simply visit

signup.millsandboon.co.uk

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

To Mom.

Contents

Cover

Introduction

Author Note

Title Page

About the Author

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Excerpt

Copyright

Chapter One

Scotland—April 1296

‘Faster, you courageous, knock-kneed, light-footed bag of bones!’ Gaira of Clan Colquhoun hugged lower on the stolen horse.

How much time did she have before her betrothed or her brothers realised in which direction she had fled? Two days, maybe three? Barely enough time to get to the safety of her sister’s home.

She couldn’t push the horse any faster. Already its flanks held a film of sweat and its breath came in heavy pants with each rapid pound of its hooves. Each breath she took matched the same frantic rhythm.

There it was! Just up the last hill and she would be safe. Safe. And there would be food, rest and the vast warmth of her sister’s comfort and counsel.

She turned her head. There was no sign of pursuit. Her heart released its fierce grip and she eased up on the reins.

‘We made it. Just a bit more and you can eat every last grain I can beg from Irvette.’

She smelled the fire before she crested the hill. The stench was a mixture of blackened smoke, heat, dried grass and rotting cow. The horse sidestepped and flicked its head, but she kept its nose forward until she reached the top.

Then she saw the horror in the valley below. Reeling, she fell upon the horse’s neck and slid down the saddle. Her left ankle twisted underneath her as it took the brunt of her descent. She didn’t feel the pain as she heaved her breakfast of oatcakes and water.

When she was emptied, she felt dry dirt under her hands, crunching grass under her knees. Her horse was no longer by her side.

She stood, took a deep breath and coughed. It wasn’t rotting cow she smelled, but burnt hair and charred human flesh.

The stench was all that remained of her sister’s village. The many crofters’ huts resembled giant empty and blackened ribcages. There were no roofs, no sides, just burnt frames glowing with the fire still consuming them.

The entire valley looked as if a huge flaming boulder had crashed through the kindling-like huts. Large twisted and gnarled swirls of black heat and smoke rose and faded into the morning sky.

She could no longer hear anything. There were no birds chirping, no rustling of tall grass or trees and no buzzing insects. All of Scotland’s sounds were sucked out of the air.

Her heart and lungs collapsed. Irvette. Her sister. Maybe she wasn’t down there. She wouldn’t think. Pushing herself forward, she stumbled as her ankle gave way. It would be useless for the sloped descent.

She looked over her shoulder. Her horse skittered at the base of the hill. He was spooked by the heat and smells; she could call, but he would not come.

Bending to her hands and knees, she crawled backward down to the meandering valley. Blasts of heat carried by the wind ruffled up her tunic and hose. She coughed as the smoke curled around her face. When she reached the bottom, she straightened and took off the brown hat upon her head to cover her mouth.

Her eyes scanned the area as she tried to comprehend, tried to understand what she saw. Thatch, planks of wood and furniture were strewn across the path between the huts and so were the villagers: men, women, dogs and children.

Nothing moved.

They were freshly made kills of hacked and charred bodies. The path was pounded by many horses’ hooves, but there weren’t any horses or pigs or even chickens.

Dragging her left foot through the ashes behind her, she stumbled through the burning village, which curved with the valley.

At the dead end of the devastation, the last of the crofters’ huts stood. More intact than the others, it was still badly scarred by the flames and its roof hung limply with pieces falling to the ground.

Near the doorway, she looked at the two burned and face down bodies of a man and a woman. The man was no more than a husk of burnt flesh with his head severed from his body.

But it was the woman’s she recognised: the flame-coloured hair burnt at the tips and the cream-coloured gown smeared with dirt. Blood spread along the gown in varying flows from the two deep sword-thrusts in the stomach. Irvette.

Her world twisted, sharpened. She suddenly heard the popping and hiss of water, the crash of brittle wood splintering into ashy dust and a high keening sound, which increased in volume until she realised the sound came from her.

She stopped, gathered her breath and then she heard it: a whisper, a cry, fragile and high-pitched. She quickly limped into the hut and weaved before crashing to her knees.

‘Snakes and boars,’ she whispered. ‘Thank God, you’re alive.’

Chapter Two

Scotland, on the border with England

Sheets of rain drove down on the battlefield, making mud out of dirt and streams in the dips and cracks of the earth.

Robert of Dent fought on foot. His black surcoat and hose were plastered to his body. His quilted black gambeson, saturated with mud, no longer protected him from the chainmail of his hauberk and chausses. Long hair streamed over his face and shoulders impairing his sight, but it did not matter. The rain provided no visibility. He could no longer see his men, whether they stood or had fallen; he could no longer call out, for the downpour drowned out sounds. All he could hear was the harshness of his own breath.

Rain fell, but blood sprayed the air. It was everywhere: on his clothes, in his hair, streaming through his mouth and beard. His sword from tip to hilt was slick with it and it flowed from his wrists to his shoulders.

He knew his enemy only by the swing of a sword towards him and he thrust upward, sinking his own sword deep through the man’s neck. The blade stuck fast and he wrenched it free.

Shoved off balance, he had just enough time to block the fall of an axe. The reverberation of the strike pushed him to his knees and he quickly rolled over spikes of broken arrows to miss his enemy’s killing blow. The Scotsman’s axe sunk deep into the mud. Still rolling, he sliced his sword across the man’s shins. The man fell. He stood and plunged his sword into the Scotsman’s chest.

Spitting the mud and blood out of his mouth, he fought, moving forward, trying to keep his balance as he stepped over the dead covering the ground. His boots slipped as he continued to parry and thrust, block and kill.

He emptied himself of everything but the battle. He did not think of glory or survival. He did not count the enemies he felled. He did not think at all. He was muscle and training and sword.

When this battle was done, there would be the removal of the wounded and dead. Then there would be food, drink, sleep and another battle. He knew nothing else, breathed nothing else. His past was forgotten by his will alone.

* * *

Robert stepped through the mud and tangled grass of the battlefield. He could hear the screams of his men, their cries of pain and, worse, the gaping silence from those who could no longer make a sound.

He swallowed his anger. Too much haste had cost them dearly. He was tired, but his men were worse. Since King Edward had rallied more soldiers, the battles were more frequent, more driven. The men had not had enough time to rest between the fights and as a result, he saw men fall today who had no place on the battlefield.

He looked up. Hugh of Shoebury slowly walked an abandoned destrier towards him. Hugh was tall and lean like King Edward, but there the similarities stopped. Hugh was no seasoned ruler, but young with blond hair, blue eyes and skin so white, a touch of the sun burned it red.

‘How many?’ he asked when Hugh was close enough.

‘Too many to count,’ Hugh replied, his hand on the shredded bridle of the destrier. ‘What are the instructions now?’

‘We pull camp and wait for the king’s reports from the east.’

‘At least we get to rest.’

Robert stopped surveying the field and turned to walk to camp. ‘Let us hope for a long reprieve. There are too many complications with this war we wage.’

‘Hardly a war. Balliol hasn’t the troops to defend against King Edward’s fleet.’

‘Since Balliol was crowned, it made sense for us to strengthen the northern defences. I have too many questions why a fleet of our countrymen was sent north as well.’

Hugh shrugged. ‘It is not for us to know. And since we followed orders, the king could hardly fault the infamous “Black Robert”.’

He ignored Hugh’s use of his title. He did not welcome the description of him on even the most favourable of days. This day was not favourable. ‘It will take several weeks to recover.’

‘Aye, but he will be pleased at what we accomplished today. Even what happened up north could not weaken his resolve.’

‘What do you mean, “what happened up north”?’

‘You did not hear? There’s a small village, Doonhill, tucked into a valley just northwest of Dumfries. A faction of men, under Sir Howe, went there when it appeared we would not be victorious.’

‘Howe purposefully pulled his troops when the battle was not yet over?’ He quickened his stride. ‘That could have cost us victory!’

‘Aye, but Sir Howe said he had to retreat or all of them would have died.’

The story was sounding familiar. ‘Howe? Is he the one who commanded and pulled the destriers at Lockerbie?’

‘The very same.’ Hugh coughed into his hand.

‘So the bastard thought he could do it twice?’ His jaw tightened. ‘What happened at Doonhill?’

‘It was a small village, but apparently had many women.’

He did not need to hear any more. He was not naive and knew rapine happened as a result of war. Indeed, many men thought it was their due.

‘What did the king do for the women?’

‘Nothing.’

He stopped and turned his entire focus on Hugh. They had almost reached the camp and he wanted to finish this conversation in private. ‘What do you mean, “nothing”?’

‘There could be no repairs. The king said he’d be sending a message to Balliol about the incident in case there were repercussions.’

‘Why would there be consequences? Why does he not pay the men of Doonhill as he has done in the past?’

‘There are no men, Robert, or women, or children to pay,’ Hugh spoke slowly. ‘Our men destroyed the entire village.’

His head and body filled with anger and disbelief. Even to his own ears, when he spoke, he sounded distant. ‘How is that possible?’

‘It is the risk of war.’ Hugh’s horse yanked impatiently at his bit. ‘Pray excuse, I need to get this horse to rest and food.’

He shook off the hesitation he felt in following Hugh. Long ago he had stopped looking to correct the past and the destruction of the village could not be undone. Dismissing his thoughts, he patted Hugh on the back. ‘I will come. I find I must be more hungry and tired than I thought.’

* * *

Robert crested the hill. He still did not know what had compelled him to come. Hugh hadn’t been pleased he travelled alone in enemy territory. But it wasn’t logical for others to make the journey. Now that he saw the valley, it seemed meaningless.

The day ended, but the impending darkness did not dim the devastation. It was worse than his dream. Howe would have to pay for what he’d done.

His horse impatiently tossed his head and he tightened the hold on the reins. It would never make a good war horse. What good was a horse if a few smells made it shy? And there were smells. The valley was steeped in death.

Dismounting, he walked down. The stench of decaying bodies and burnt wood accosted his nose. He breathed through his mouth and stopped.

There were no bodies. He could smell them, he had been in Edward’s wars too long to mistake the smell, but they were not strewn along with the furniture or broken pots. He quickened his pace.

Close to the lake, he came across a large plot of freshly tilled land. It was a garden. The stench was so strong now he wished he didn’t have to breathe at all.

There were fresh, shallow graves mixed with patches of burnt vegetable stalks. The bodies were laid close together and there was a long scrape made in the dirt between the bodies and the garden. The bodies had been dragged to their resting place.

It was a gravesite and a gravesite meant survivors burying their dead. There were footprints, too, but it looked as if they were the same size and at least one foot dragged.

He scanned the surrounding area again, but he could hear nothing. Everything was still.

Was one man trying to bury many? He wondered why anyone would bother. There was nothing left in the village to save, no way of healing and rebuilding after the destruction Howe’s men had caused.

Knowing he was not alone, he unsheathed his sword. Keeping his weapon low and at his side, he carefully walked towards the lake.

Then he heard it: a scrape, quick and loud, coming from one of the partially burnt huts.

Wanting to make sure his words were heard, he waited until he was closer. ‘I come in peace!’ he said in English and again in Gaelic. ‘Please, I mean you no harm.’

Another scrape—it sounded like metal. There was someone definitely inside the hut.

‘I offer help.’ He tried to make his words as convincing as he could. Whoever was in there, they could not have warm hospitality on their minds.

Approaching the open doorway, he raised his sword to hip level. He would rather have waited until whoever was in the hut had come out, but the person inside could be injured and needing his help.

Setting his shoulder in first, he entered the hut. The moon’s light slashed through the burnt roof. The one room was small, square, but he could see little else. There was no time to avoid the small iron cauldron swinging towards his head.

Chapter Three

‘Oh, cat’s whiskers around a mouse’s throat, I’ve killed him!’

Gaira stopped the still-swinging cauldron and swallowed the sharp bile rising in her throat. With shaking knees, she knelt beside the man. Slowly, so slowly, she lowered her hand to his mouth and felt hot breath against the back of her hand. He breathed!

Her heart swiftly rose. Dizzy, she closed her eyes and drew in a steadying breath. When she was sure she could, she opened her eyes to inspect him.

He was a large man, not taller than any Scotsman, but maybe thicker, and his chest was so broad it was surely carved from the side of mountains. She could not discern his face in the moonlight, but she could see his hair was long, wild and he had let his beard grow unkempt.

His hair and beard puzzled her, for it was very un-English and this man grew his as if he were the lowliest of serfs with no comb. But an English serf would not be this far north and all alone.

Carefully, she felt along his sides for a pouch or weapons. He smelled of cedar, leather and open air. Only the fine, soft weave of his clothing gave beneath her fingers. His body, warm through his tunic, was hard, unforgiving. She frowned at the fanciful word. A body could not be unforgiving.

Feeling along his front, her palms suddenly dampened, tingled, and she stopped at his hips. She wanted to continue her exploring, but she realised it wasn’t to find weapons.

What was wrong with her? She had three older brothers. This man could be no different. But he feels different. She squashed that thought. Foolishness again. If her hands felt strange or hot, it was because she was scared he’d awaken. Aye. Plain nervousness was all she felt.

Willing her hands to obey, she moved them around his waist. Did his breathing change? No. His eyes were still closed. Taking a steadying breath, she felt the flat ripples of his waist, the knot of his hip bones. She stilled her breathing as she slid her hands down each bulging cord of his legs. At a strap near his boots she felt the hard hilt of a dagger. Pulling it out, she felt the weight and heavily carved decoration on the handle.

‘Nae a peasant, are you?’ Setting the dagger aside, she felt along his broad arms and immediately felt the cold steel of an unsheathed sword at his side. Her skin prickled with anger.

‘Even if you hadn’t spoken, I’d know you’re English for the liar you are. Peace! Hah! What man comes in peace when his sword is drawn?’

With trembling fingers she unwrapped his fingers from his sword. Wobbling at its weight, she set it on the other side of the room and grabbed the rope hanging at her waist. It wasn’t long enough to tie his hands and feet, but it was mostly his hands she was worried about.

Her heart thumped hard against her chest. She was worried about other parts of him, too. She was not so naive to think this man was safe. His muscled body, his ability to speak English and Gaelic, were testament to a soldier’s training.

Without a doubt, he would have a foul temper when he woke. But what choice did she have? She had hid in the hut. It wasn’t her fault the brastling man had entered. She’d had to swing the cauldron and protect herself.

But now what? He was sure to awaken soon. He was English, but she didn’t know if he’d burned the village. She couldn’t take any chances. It wasn’t just her own life she had to worry about.

‘Think, Gaira, think!’ She had his weapons. They might give her some control. Quickly finishing the knot, she scrambled back into the scant shadows to wait.

* * *

‘What do you mean she’s not at her brother’s?’ Busby of Ayrshire spat on the ground. The glob hit square in the centre of the old leather shoe worn by his messenger.

‘She’s not on Colquhoun lands, my laird,’ the messenger stuttered. ‘Her brothers were most surprised to see me.’

Busby rubbed his meaty hands down the front of his rough brown tunic. The only satisfaction in this bit of news? His cowering messenger was afraid. He liked it when they were afraid.

‘Did you explain to that whoreson Bram if he dinna produce his sister to me within a sennight, our bargain was off?’

‘Aye. We were given leave to search the castle.’

Busby took a step forward. ‘Did you tell them for this bit of inconvenience, I demand the further compensation of five sheep? And I wouldn’t have taken her had I known she was so bothersome? And if they want war between our clans they’ll have it?’

‘Aye, my laird.’ The messenger bent his body to look up. ‘I told them all, every bit of it. It dinna make nae difference. We searched everywhere and there was nae sign of her.’

The wench had been missing for three days while he waited for the messenger to bring her back or bring him news. The fact he had neither fuelled his fury.

‘Tell me their response,’ Busby demanded.

The messenger shifted his feet and almost imperceptibly took a step back. ‘They were not pleased.’

‘What. Do. You. Mean?’

The messenger took a full step back. Busby let him. It did not matter. The messenger was still within his reach.

‘They were most displeased. I, er, feared for my life. They said something about losing their sister and, if anything should happen to her, it’s on your head.’

‘What?’ he roared, and clenched one hand around the man’s thin neck.

A croaking sound escaped the man’s mouth and Busby eased his grip. ‘They told me they’d search the area from here to Campbell land first, but you should go south.’

He released the man, who scrambled back. ‘Go south? What for?’