полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 70, No. 433, November 1851

The nature and objects of the Agricultural Relief Associations may be gathered from the report of the Suffolk meeting, lately held at Bury St. Edmunds. The assumption of all the speakers was, that Protection cannot be expected either from the present or the future Parliament.

"Politicians," said one gentleman, "were every day shifting their ground. Men who a few short months ago threatened to assume the reins of Government, with the express design of reversing the policy of the last few years, were now faltering in their purpose, and confessing both their inability and unwillingness to effect these changes."

Another spoke as follows: —

"It was generally known, that while the farmers were asleep the Free-Trade policy came into operation. This at once cut off not less than 20 per cent of the capital employed in farming. This blow the farmers felt very keenly. They at once began to open their eyes, unstop their ears, and to unloose their tongues. They earnestly inquired what steps should be taken by them in the new circumstances under which they were placed. They heard various voices in reply, but the loudest and most powerful of these assured them that they would go back to Protection, and that by next Session too. Next Session passed, however, without exhibiting the least prospect of that result, and they had been going on, Session after Session, until the present moment, when they seemed farther from Protection than ever. Others told them to lay out all their capital on land, and they would be sure to get remuneration. They had done that too, and their capital was gone without any prospect of remuneration."

Another gentleman, hitherto known as a staunch Protectionist, thus announced his reasons for joining the movement: —

"The fact was, that when he found members of the House of Commons, who had been returned to Parliament for the express purpose of supporting Protection, saying, behind the scenes, that it was impossible to expect Protection back again; and when he found members of the House of Peers telling him that if they stood out for Protection it would cost them their coronets, he was forced to come to the conclusion that the voice of the people had doomed these laws. He then began to ask himself this plain and simple question – if they give the country cheap corn, won't they give us cheap taxation? He was willing to grow corn against any man, come from where he might; but, at the same time, he must have a fair field to do it in."

Here are the views of the society as contained in the chairman's summary: —

"When their agricultural distress had been relieved by the repeal of the malt-tax, by the permanent fixation of tithe on an equitable basis, by the extinction of church-rates, by a revision of the county expenditure, the abolition of the game-laws, the removal of all restrictions on the cultivation of land, a change in the law of distress, the rights of the tenant-farmers recognised, the abominable abuses of the poor-law corrected, and when the bulk of taxation was shifted from the shoulders of the productive to those of the unproductive classes – from industry upon wealth – then might they hope that honesty, industry, and perseverance would meet their due reward."

We do not make these quotations with any intention of criticising the opinions expressed. We simply lay them before our readers as a specimen of that spirit which is now possessing the farmers – a spirit engendered by wrong, and strengthened by the suffering of years. If anything could make us believe that coronets are in danger of falling, it is the expression of such views on the part of men who hitherto have been the best defenders of the Constitution, and the most averse to yield to any of the impulses of change. But, as we have already said, we cannot blame the speakers. If they are convinced in their own minds that a return to Protection is impossible, their condition is such that they must necessarily have recourse to any expedient, however desperate, which can afford them the prospect of relief. We have long foreseen this crisis. Situated as Great Britain is, the choice lies simply between a return to Protection to Labour, and an assault on the public burdens. There is no other alternative. Cheapness may be established as the rule, but cheapness cannot co-exist with heavy taxation. To hope that the burden can be shifted from one shoulder to another is clearly an absurdity. If it is to be sustained, the productive classes must have the means of sustaining it. If those means are denied them, the burden is altogether intolerable.

It is not a little instructive to remark that, even now, the supporters of Free Trade are compelled to stop and leave their scheme unfinished. They cannot carry it out in its integrity without ruining the finances of the country. They have exposed the farmer to unlimited competition in produce, but they still continue to restrict the sphere of his industry and production. The malt-tax is a heavy burden upon him, and he is specially prohibited from growing tobacco, or engaging in the manufacture of beetroot sugar. These restrictions, say the Free-Traders, are absolutely necessary for revenue. Granted; but if you put on restrictions, are you not bound to give an equivalent? As for the argument in favour of the malt-tax, that it is the consumer who really pays the duty, that might be extended with equal justice to the instance of raw cotton. Why is barley, the produce of our own country, to be taxed, and cotton, the produce of a foreign country, to be exempted? Besides this, we have always understood that beer, tobacco, and sugar, are articles which enter largely into the consumption of the agricultural as well as that of other classes; so that here is a grievance totally opposed to the principles of Free Trade, and yet supported and perpetuated by the very men who have adopted Free Trade as their motto! We instance these things as proofs that Free Trade never can be made, in the strict sense of the word, the law and system of the land, so long as the present enormous expenditure is continued; and in saying this, we hope it will be understood that we are as much opposed as ever to the views of the party who are for cutting down our national establishments.

We anticipate, in the course of next Session, to hear many propositions made on the subject of adjustment of taxation. Each class is anxious to be freed from its own peculiar burdens, and to devolve them upon others; and certainly never was there any case so strong or so urgent as that which can be brought forward on the part of the agriculturists. But who is to relieve them? Will any other class submit to the transference which is necessarily implied? Will the manufacturers or the capitalists undertake to provide for the six millions which at present they are most unjustly wresting from the owners and occupiers of the soil? Here is the real difficulty. Justice, we know, is not regarded as an indispensable element of taxation: if it were so, the income-tax would never have been imposed in its present form. If the claims of the farmers who are banded together for agricultural relief were granted, immediate national bankruptcy would be the result. This is the grand dilemma in which we are placed by the Free-Traders. Either a gross and palpable act of injustice and oppression must be perpetuated – so long at least as the victims have the means of payment – or, as was long ago prophesied, the capitalists and the fundholders must suffer. The truth is, that the productive power of the country cannot meet the demands upon it in the shape of taxation if it remains exposed to unlimited foreign competition.

In order properly to comprehend this point, which is one of the utmost importance, it is necessary to discard theory altogether, and to adopt history as our guide. The financial system of Great Britain, acting upon and influencing the commercial arrangements and social relations of the country, is not difficult of comprehension if we trace it step by step; and without a due understanding of this, and the vast influence which monetary laws exercise over the wellbeing and progress of a nation, it is impossible for any one to form a sound judgment on the conflicting principles of Protection and Free Trade, or to discover the true and only source of the difficulties which now surround us. It is the misfortune of the present age that so little attention is paid to the abstruser portions of history, which, in reality, are the most valuable for us. Wars of succession or conquest, naval engagements, records of intrigue or details of diplomatic dexterity, have a peculiar charm and interest for readers of every kind; but few take the pains to go more deeply into the subject, and investigate in what manner such events have affected the resources of a country, and whether, by diminishing its wealth or by stimulating the energies of its population, they have lowered or raised its position in the scale of nations. That portion of history which relates to external events is worthless for practical purposes, unless we combine with it the study of that portion which relates to its finance. Under the modern system, now universal throughout Europe, which leaves the debts and engagements of former generations to be liquidated or provided for by the next, no man can be called a statesman or politician who has not addicted himself to these studies.

The Funding System, as is well know, began with the Revolution, and has continued up to the present hour. It was strenuously opposed and vigorously assailed by some of the most able and clear-sighted in the country, such as Bolingbroke, David Hume, and Adam Smith, who from time to time pointed out the consequences which must ultimately ensue from this method of mortgaging posterity, more especially if the burden were allowed to increase without any steps being taken to provide for its ultimate extinguishment. It is the peculiarity of a debt so constituted, that for a time it gives great additional stimulus to the energies of a country. It enables it to prosecute conquests, and to undertake designs, which it could not otherwise have achieved; and it is not until long afterwards, when the payment of the interest or annual charge becomes a severe burden upon a generation which had no share in contracting the debt, that the mischievous effects of the system become apparent. At the outbreak of the French Revolution, the public debt of Great Britain amounted to £261,735,059, and the annual charge was £9,471,675. A very large portion of this debt was incurred for the war waged with our American colonies.

At that time the currency of the country was placed on the metallic basis, but the great drain of the precious metals occasioned by the enormous subsidies which Great Britain furnished to her allies on the Continent, to engage their support against the revolutionary armies of France, reduced the nation to the very verge of bankruptcy, and necessitated in 1797 the suspension of cash payments. The immediate effect of this step upon the finances of the country has been so justly, and at the same time so clearly, stated by Mr Alison in his History of Europe, and the consequences of the subsequent return to the old system of cash payments, after their suspension for nearly a quarter of a century, are so graphically depicted, that we cannot do better than entreat the attention of the reader to the following extract: —

"This measure having been carried by Mr Pitt, a committee was appointed, which reported shortly after that the funds of the Bank were £17,597,000, while its debts were only £13,770,000, leaving a balance of £3,800,000 in favour of the establishment; but that it was necessary, for a limited time, to suspend the cash payments. Upon this, a bill for the restriction of payments in specie was introduced, which provided that bank-notes should be received as a legal tender by the collectors of taxes, and have the effect of stopping the issuing of arrest on mesne process for payment of debt between man and man. The bill was limited in its operation to the 24th June; but it was afterwards renewed from time to time, and in November 1797 continued till the conclusion of a general peace; and the obligation on the Bank to pay in specie was never again imposed till Sir Robert Peel's Act in 1819.

"Such was the commencement of the paper system in Great Britain, which ultimately produced such astonishing effects; which enabled the empire to carry on for so long a period so costly a war, and to maintain for years armaments greater than had been raised by the Roman people in the zenith of their power; which brought the struggle at length to a triumphant issue, and arrayed all the forces of Eastern Europe in English pay, against France on the banks of the Rhine. To the same system must be ascribed ultimate effects as disastrous, as the immediate were beneficial and glorious; the continued and progressive rise of rents, the unceasing, and to many calamitous, fall in the value of money during the whole course of the war; increased expenditure, the growth of sanguine ideas and extravagant habits in all classes of society; unbounded speculation, prodigious profits and frequent disasters among the commercial rich; increased wages, general prosperity, and occasional depression among the labouring poor. But these effects, which ensued during the war, were as nothing compared to those which have, since the peace, resulted from the return to cash payments by the bill of 1819. Perhaps no single measure ever produced so calamitous an effect as that has done. It has added at least a third to the National Debt, and augmented in a similar proportion all private debt in the country, and at the same time occasioned such a fall of prices by the contraction of the currency as has destroyed the sinking fund, rendered great part of the indirect taxes unproductive, and compelled in the end a return to direct taxation in a time of general peace. Thence has arisen a vacillation of prices unparalleled in any age of the world; a creation of property in some and destruction of it in others, which equalled, in its ultimate consequences, all but the disasters of a revolution."7

The immediate effect of the suspension of cash payments on the part of the State bank was an enormous increase in the circulation of paper. The prices of commodities rose to nearly double their previous value, and a period of prosperity commenced, at least for one generation. During the twenty-two years which elapsed from the suspension of cash payments in 1797 down to 1819, when their resumption was provided for by Act of Parliament, or at least during eighteen years of that period, reckoning down to the re-establishment of peace in Europe, the career of England has no parallel in the annals of the world. The vast improvements and discoveries in machinery which were made towards the latter end of the century – the inventions of Hargreaves, Arkwright, Cartwright, Crompton, and Watt, came into play with astounding effect at a time when Great Britain held the mastery of the seas, and could divert the supplies of raw material from all other shores except her own. During the hottest period of the war, and in spite of all prohibitions, England manufactured for the Continent. Capital, or that which passed for capital, was plentiful; credit was easy, and profits were enormous. Some idea of the rapidity with which our manufactures progressed may be drawn from the fact that, whereas in 1785 the quantity of cotton wrought up was only 17,992,882 lbs., in 1810 it had increased to 123,701,826. Under this stimulus the population augmented greatly. The rise in the value of commodities gave that impulse to agriculture by means of which tracts of moorland have been converted into smiling harvest-fields, fens drained, commons enclosed, and huge tracts reclaimed from the sea. The average price of wheat in 1792, was 42s. 11d.; in 1810, it was 106s. 2d. per quarter. Wages rose, though not in the same proportion, and employment was abundant.

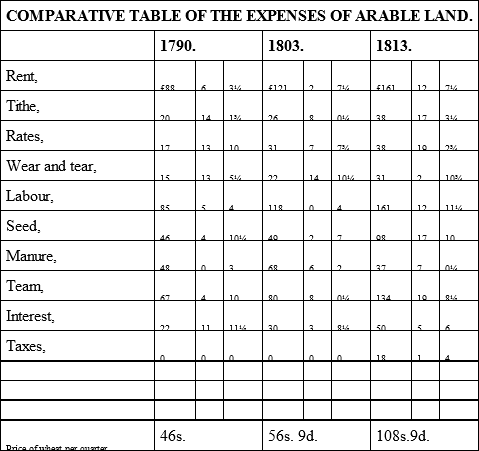

In short, the paper age, while it lasted, transcended, in so far as Britain was concerned, the dreams of a golden era. Those who suffered from the suspension of cash payments were the original fundholders, annuitants, and such landlords as had previously let their properties upon long leases. But the distress of such parties was little heard, and less heeded, amid the hum of the multitudes who were profiting by the change. The creditor might be injured, but the debtor was largely benefited. One immediate effect of this rise in prices was, a corresponding rise in fixed salaries and the expenses of government. Hence, the domestic expenditure of the country was greatly increased; new taxes were levied, and the permanent burden of the National Debt augmented to an amount which, sixty years ago, would have been reckoned entirely fabulous. As a specimen of the increased expense of cultivating arable land, it may here be worth while to insert the following comparative table, calculated by Mr Arthur Young, and laid before a committee of the House of Lords. The extent is one hundred acres: —

So long as the war lasted, the import of corn from abroad into this country was insignificant in amount. In 1814 the amount of wheat and wheat flour brought in amounted to only 681,333 quarters, being considerably above the average of years since the commencement of the century. In fact, Britain was then self-supporting. In time of war it is plain that, from our insular position, we cannot trust to any supplies beyond those which are raised at home, and there cannot be any doubt of the capability of the land to support a much larger population than that which presently exists. To those who glance superficially at the above table, the price of wheat in the year 1813 will appear monstrous, even when the great increase in the cost of cultivation is taken into account. This is the error, and it is a gross one, which has been studiously perpetuated by our statists, and even by some eminent writers on political economy. True, the price of wheat was then 108s. 9d., but it was estimated in a depreciated currency. Owing to various causes which it would be tedious to explain, the apparent difference between the value of the pound note and the guinea was far slighter than might have been expected, not amounting to more than seven or eight shillings, and actual depreciation, by sale of the notes for less than their nominal value, was by statute made penal. The price of gold and silver bullion never rose to an extent commensurate with the depreciation of the paper: in fact the coinage, as must be in the recollection of many, almost entirely disappeared, and was replaced by tokens of little intrinsic value, which served as the medium of interchange. In this depreciated and fluctuating currency commodities were valued, and by far the greater part of our National Debt was contracted. The paper pound in 1813 was probably, we may almost say certainly, not worth more than 10s. of metallic currency. In this view the quarter, estimated according to the present standard, was sold for 54s. 4½d – a price which modern statesmen allow to be barely remunerative.

If this point were generally understood, a vast amount of delusion which possesses the public mind would be dispelled. The relative value of money to commodities has been as entirely changed, by the return to cash payments, as if shillings had been substituted for sixpences. If the creditor suffered in 1797, the debtor has suffered far more severely in consequence of the Act of 1819, as we shall immediately proceed to show. Meantime, we shall entreat the reader to keep in mind that all incomes and expenditure, public or private, during the war and the suspension of cash payments, are to be estimated not by our present metallic standard, but by the fluctuating value of a depreciated currency.

When peace was established the ports were opened. Then it became evident that foreign importations, if permitted, would at once and for ever extinguish the landed interest. The annual charge of the debt alone was, in 1816, the first year of peace, £32,938,751; and the current annual expenditure £32,231,020 – in all, upwards of sixty-five millions. Had, therefore, the price of wheat in Britain been suddenly reduced to the Continental level, as would have been the case but for the imposition of the Corn Laws, the national bankruptcy would have been immediate. No argument is required to prove this and it has often struck us as singular that this crisis – for such it was – has been so seldom referred to, especially in later discussions. We are not now defending the original suspension of cash payments – a measure which, nevertheless, seems to us to have been dictated by the strongest political necessity, however baneful its results may prove to the present and future generations. We simply say, that eighteen years' operation of that system, with the enormous expenditure and liabilities which it entailed, rendered Protection necessary the moment importation was threatened, to save the country from immediate bankruptcy following on its unparalleled efforts.

It is utter folly, and worse, to say, as political economists now contend, and as ignorant demagogues aver, that the Corn Laws were originally proposed solely for the benefit of the landlords. Without the imposition of such laws, the whole financial system of Great Britain must instantly have disappeared. The amount of taxes which were required – first, to pay the interest of the National Debt, and, secondly, to meet the expenses of Government, (greatly increased by the change in the monetary laws effected in 1797) – rendered Protection to labour and to native produce absolutely indispensable. How could it be otherwise? Had wheat been sold in the British market at 46s., or even 50s., from what sources could the revenue have been levied? Under the new system, the expenses of cultivation had nearly doubled in twenty-three years – could the produce be put back to the same rates as before? So long as the monetary system then established did exist, that was clearly impossible. Protection was imperatively demanded, not by any class of the community, but by the state. To refuse it would have been national suicide. And so it was carried, doubtless very much against the inclination of the populace, who naturally enough expected that the return of peace would bring with it some substantial advantages in the shape of cheapness, and were proportionally disappointed when they discovered that the whole rent-charge of the wars, which had been so long maintained, must be liquidated before they could taste the anticipated blessings of the cheap loaf.

The return to cash payments, effected by the Act of 1819, is by far the most important event in our history since the change of dynasty. We believe that the late Sir Robert Peel, then a very young man, who was made the mouthpiece of a particular party on that occasion, really did not understand, to its full extent, the tremendous responsibility which he incurred. He acted simply as the exponent of the measure, at the instigation and by the direction of Mr Ricardo, who, under the guise of a political economist, concealed the crafty and selfish motives of the race from which he originally sprung. Ricardo was at that time considered a grand authority on matters of finance, his field of preparatory study having been the Stock Exchange, on which he is understood to have realised a large fortune. All his prepossessions, therefore, were in favour of the capitalists; and it is not uncharitable to conclude that his private interests lay in the same direction. That act provided for the gradual resumption of cash payments throughout England, to be consummated in 1823, for the establishment of a fixed gold standard, and for the withdrawal of all bank-notes under the amount of five pounds. Had this act been carried into effect in all its integrity, general bankruptcy must have immediately ensued, from the absorption of the circulating medium. The existence of the small notes, however, was respited, and this enabled the country bankers to go on for some time without a crash. Still the violent contraction of the currency, so caused, had the necessary effect of spreading dismay throughout all sections of the community. The circulation of the Bank of England, at 27th February 1819, was £25,126,700. On the 28th February 1823, it was contracted to £18,392,240. At the former period its private discounts amounted to more than nine millions; at the latter, they were considerably under five. As a matter of course, the country bankers were compelled to follow the example of the great establishment, and the immediate results of this grand financial measure may be described in a few words. The tree was thoroughly shaken. According to Mr Doubleday —