полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 423, January 1851

That bribe was the removal of the import duties on grain and provisions to Great Britain. Let the secret instigators of the movement – the men who organised the machinery of the League – disguise the fact as they may, that, and that alone, was the actual cause of our lowered tariffs and the ultimate repeal of the corn-laws. The Manchester Chamber hoped – most vainly, as it now appears – that, by giving a new stimulus to agriculture in America, at the expense of the vast body of British producers, they could at least ward off the evil day when the American manufacturer should be able to annihilate their trade, by depriving them of the enormous profits which they realised on the conversion of the raw material into yarn. What these profits were will appear from the fact that the price of cotton wool at Liverpool, in 1843-4, was 6d., whilst twist was selling at 101⁄4d.; and that in 1844-5, the price of wool having fallen to 4d., the market value of twist was 113⁄4d. Hitherto the prices, as fixed in England, have regulated those of the world.

That the late Sir Robert Peel, himself a scion of the cotton interest, should have been swayed by such considerations, is not, perhaps, remarkable; but that any portion of the landed gentry, of the producers for the home market, the labourers and the mechanics of Great Britain, should have allowed themselves to be deceived by the idea, that diminished or depreciated production could possibly tend either to their individual or to the national advantage, will hereafter be matter of marvel. We who know the amount of artifice and misrepresentation which was used, and who never can forget the guilty haste with which the disastrous measure was hurried through both Houses of Parliament, without giving to the nation an opportunity of expressing its deliberate opinion, feel, and have felt, less surprise than sorrow at the event. With British feeling, however, we have at present nothing to do; our object is to trace the effect which our relaxation has exercised upon American policy.

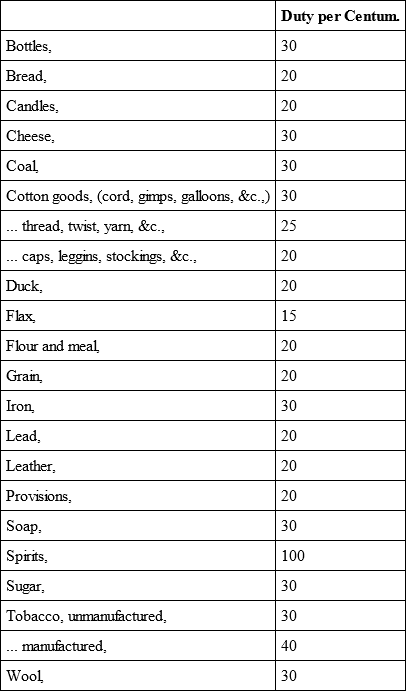

The American tariff of 1846, denounced by the Protectionists of the States as injurious to home interests, and supported by the Free-Trade party, imposes, among others, the following duties: —

These duties are somewhat lower, though not materially so, than the former tariff of 1842; but they certainly offer no inconsiderable amount of protection to home industry and produce. We have already seen the progress which has been made by the American cotton manufacturers, iron-masters, and miners; and it is now quite evident that, unless that progress is checked – which it only can be by the will of the Americans – our exports to that quarter must naturally decline. This is not our anticipation merely; it has been expressed openly and anxiously in the columns of the Free-Trade journals. In the iron districts of Scotland and Staffordshire, the apprehension that henceforward the American market will be generally closed against them, is, we know, very prevalent; and the following extract from the report of the Morning Chronicle, (April 11, 1850,) on the condition and prospects of the iron trade in the spring of 1850, applies exactly to the opening of 1851: —

"The present state of our commercial negotiations with the United States, particularly in relation to the exportation of iron from this country, promises greatly to aggravate existing evils. It is feared by many largely interested in the iron manufacture of this neighbourhood, that the efforts of Sir Henry Bulwer at Washington to obtain a modification of the American tariff, with respect more especially to the importation of iron, will prove abortive for some time to come. Our exports of iron from South Staffordshire are said to be already considerably reduced; and should our Transatlantic friends continue, as they threaten, their restrictive commercial policy, business in these important manufacturing districts must of necessity be still more limited than it is at the present moment."

What the prospects are of future relaxation may be gathered from the following extract from the message of President Fillmore to Congress, which has reached us whilst writing this article. We observe that the Times is bitterly chagrined to find that the President "has stated and commended the false doctrine of Protection." Was it to be expected that he would have done otherwise, seeing that the vast majority of the American public are thoroughly imbued with the same doctrines, however false and heretical they may appear in the eyes of Manchester?

"All experience has demonstrated the wisdom and policy of raising a large portion of revenue for the support of Government from duties on goods imported. The power to lay these duties is unquestionable, and its chief object, of course, is to replenish the Treasury. But if, in doing this, an incidental advantage may be gained by encouraging the industry of our own citizens, it is our duty to avail ourselves of that advantage.

"A duty laid upon an article which cannot be produced in this country, such as tea or coffee – adds to the cost of the article, and is chiefly or wholly paid by the consumers. But a duty laid upon an article which may be produced here stimulates the skill and industry of our own country to produce the same article, which is brought into the market in competition with the foreign article, and the importer is thus compelled to reduce his price to that at which the domestic article can be sold, thereby throwing a part of the duty upon the producer of the foreign article. The continuance of this process creates the skill, and invites the capital, which finally enable us to produce the article much cheaper than it could have been procured from abroad, thereby benefiting both the producer and the consumer at home. The consequence of this is, that the artisan and the agriculturist are brought together; each affords a ready market for the produce of the other, the whole country becomes prosperous, and the ability to produce every necessary of life renders us independent in war as well as in peace.

"A high tariff can never be permanent. It will cause dissatisfaction and will be changed. It excludes competition, and thereby invites the investment of capital in manufactures to such excess, that when changed it brings distress, bankruptcy, and ruin upon all who have been misled by its faithless protection. What the manufacturer wants is uniformity and permanency, that he may feel a confidence that he is not to be ruined by sudden changes. But, to make a tariff uniform and permanent, it is not only necessary that the law should not be altered, but that the duty should not fluctuate. To effect this, all duties should be specific, wherever the nature of the article is such as to admit of it. Ad valorem duties fluctuate with the price, and offer strong temptations to fraud and perjury.

"Specific duties, on the contrary, are equal and uniform in all ports and at all times, and offer a strong inducement to the importer to bring the best article, as he pays no more duty upon that than upon one of inferior quality. I therefore strongly recommend a modification of the present tariff, which has prostrated some of our most important and necessary manufactures, and that specific duties be imposed sufficient to raise the requisite revenue, making such discrimination in favour of the industrial pursuits of our country as to encourage home production without excluding foreign competition. It is also important that an unfortunate provision in the present tariff, which imposes a much higher duty upon the raw material that enters into our manufactures than upon the manufactured article, should be remedied."

So that America, the great democratic state on which we relied for reciprocity, is going ahead, not, as our Free-Traders foretold, in their direction, but precisely on the opposite tack.

What is there wonderful in this? Was it likely that a country, possessing within itself the raw material in abundance, and, so far as cotton was concerned, having a virtual monopoly of its growth, should for ever refuse to avail itself of its natural advantages, and to stimulate agriculture by giving it that enormous increment of consumption which must arise from the establishment of domestic manufactures? Does not common sense show us that, the nearer the point of exchange can be brought to the exchanging parties, the more advantageous and profitable to both parties must that interchange necessarily become? Unquestionably it is for the interest of the American planter to have the manufactory brought as close as possible to his plantation, seeing that thereby he would avoid the enormous charges which he bears at present, both in land carriage and freightage – charges which, of themselves, go a great way towards the annihilation of his profit. Add to this that those charges on the raw material necessarily enhance the price of the fabric when converted by British machinery, and again transported to America, and it must become evident to every one how largely the American planter is interested in the foundation and success of American manufactures. The interest of the agriculturist is equally great. For him a steady market at his own door, such as extended manufactures alone can give, is the readiest and most certain source of wealth and prosperity. What he wants is regular consumption, and the nearer the customers can be found, the greater will be the demand, and the more profitable the supply.

We need not, however, argue a matter which has been already settled on the other side of the Atlantic. It suffices us to know that, in all human probability, America will persevere as she has begun, taking every advantage which we are foolish enough to give her, and yet adhering to her system of protecting domestic labour, and of riveting more closely than before all branches of industry by the bonds of mutual interest. Such clear, distinct, and philosophic principles as are enunciated by a late American writer make us blush for the confused, absurd, and contradictory jargon which of late years has been proffered to the world, with so much parade, as the infallible dicta of British political economy.

"A great error exists in the impression now very commonly entertained in regard to national division of labour, and which owes its origin to the English school of political economists, whose system is throughout based upon the idea of making England 'the workshop of the world,' than which nothing could be less natural. By that school it is taught that some nations are fitted for manufactures and others for the labours of agriculture; and that the latter are largely benefited by being compelled to employ themselves in the one pursuit, making all their exchanges at a distance, thus contributing their share to the maintenance of the system of 'ships, colonies, and commerce.' The whole basis of their system is conversion and exchange, and not production, yet neither makes any addition to the amount of things to be exchanged. It is the great boast of their system that the exchangers are so numerous and the producers so few; and the more rapid the increase in the proportion which the former bear to the latter, the more rapid is supposed to be the advance towards perfect prosperity. Converters and exchangers, however, must live, and they must live out of the labour of others; and if three, five, or ten persons are to live on the product of one, it must follow that all will obtain but a small allowance of the necessaries and comforts of life, as is seen to be the case. The agricultural labourer of England often receives but eight shillings a-week, being the price of a bushel and a half of wheat.

"Were it asserted that some nations were fitted to be growers of wheat and others grinders of it, or that some were fitted for cutting down trees, and others for sawing them into lumber, it would be regarded as the height of absurdity, yet it would not be more absurd than that which is daily asserted in regard to the conversion of cotton into cloth, and implicitly believed by tens of thousands even of our countrymen. The loom is as appropriate and necessary an aid to the labours of the planter as is the grist-mill to those of the farmer. The furnace is as necessary and as appropriate an aid to the labours of both planter and farmer as is the saw-mill; and those who are compelled to dispense with the proximity of the producer of iron labour are subjected to as much disadvantage as are those who are unable to obtain the aid of the saw-mill and the miller. The loom and the anvil are, like the plough and the harrow, but small machines, naturally attracted by the great machine, the earth; and when so attracted all work together in harmony, and men become rich, and prosperous, and happy. When, on the contrary, from any disturbing cause, the attraction is in the opposite direction, and the small machines are enabled to compel the products of the great machine to follow them, the land invariably becomes poor, and men become poor and miserable, as is the case with Ireland."

In short, the American system is, to stimulate production by creating a ready market at home, and, as the best means of creating that market, to encourage the conversion of the raw material within the United States, by laying on a protective duty on articles of foreign manufacture. The British system now is, to discourage home production, and to sacrifice everything for the desperate chance of maintaining an unnatural and fortuitous monopoly of conversion, not of our own raw material only, but of that of other countries. In the attempt to secure this exceedingly precarious advantage – which, be it remembered, does not conduce to the prosperity of the great majority of the nation – our rulers and politicians have deliberately resolved that agriculture shall be rendered unprofitable; and that the bulk of our artisans, who can look to the home market only, shall henceforward be left unprotected from the competition of the whole world. It needs little sagacity to predict which system is based upon sound principles; or which, being so based, must ultimately prevail. Our economists never seem to regard the body of British producers (who, as a class, are very slightly interested in the matter of exports) in the light of important consumers. If they did so, they could not, unless smitten by judicial blindness, fail to perceive that, by crippling their means, and displacing their labour, they are in effect ruining the home market, upon which, notoriously, two-thirds even of the converters depend. The stability of every state must depend upon its production, not upon its powers of conversion. The one is real and permanent, the other liable to be disturbed and annihilated by many external causes. A country which produces largely, even though it may not have within it the means of adequate conversion, is always in a healthy state. Not only the power, but the actual source of wealth is there; and, as years roll on, and capital accumulates, the subsidiary process of conversion becomes more and more developed, not to the injury of the producer – but to his great and even incalculable advantage.

The natural power of the production of Great Britain, as compared with other states, is not very high. Its insular position, and the variableness of its climate, renders the quality of our harvests uncertain; but that uncertainty is perhaps compensated, on the average, by our superior agriculture, and the vast pains, labour, and capital which have been expended on the tillage of our land. Our meadows, downs, and hill pastures have, however, been most valuable to us in furnishing a better quality of wool than can elsewhere be obtained in Europe – an advantage which our forefathers perceived and wisely availed themselves of – for, as early as the reign of Edward III., manufacturers from Hainault were brought into this country by the advice of Queen Philippa, and laid the foundation of the most prosperous, healthy, and legitimate trade which we possess. Ever since, the woollen manufacture has been inseparably connected with the interests of the British soil. Few luxuries, or even such articles of luxury as are now considered necessaries, can be grown in Great Britain. For wine our climate is unsuited; but there is nothing whatever to prevent us – except a system which calls itself, though it is not, Free Trade – from growing the coarser kinds of tobacco, and from establishing manufactories of sugar from beet-root. Our stock of minerals is great – almost inexhaustible – and to this fact we must look for our singular pre-eminence during so many years in Europe. Our unlimited supply of coal and iron gave us an advantage which no other European nation possessed – it was, in fact, virtually a monopoly – and upon that we built our claim to become the workshop of the world. Nor was the claim in any degree a preposterous one. That singular monopoly of minerals – for such it seemed – gave us the actual power, if judiciously used, of controlling the process of conversion, not only here, but elsewhere throughout the globe. Manual labour, it mattered not what was the distance, had no chance at all against the triumphs of machinery; and hence our commerce extended itself far and wide, to savage as well as civilised nations, and our arms were used to force a market where it could not otherwise be obtained. This, if not our strength, was undoubtedly the cause of our supremacy, and even of our extended colonisation; and as we obtained command of a raw material of foreign growth, so did we adapt our machinery to convert it into fabrics for the world.

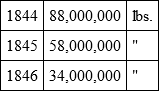

It is by no means a pleasant matter to recur to certain particulars in our commercial and manufacturing history. We found the East Indies in the possession of a considerable manufacture of cotton, the producer and the converter being there reciprocally dependant. That we have stopped, the object being to compel the Hindustani to receive his clothing direct from Manchester. And we have succeeded so far that, last year, our exports to Hindostan were so great, that, by lumping them in the general account, our statists were able to furnish what appeared to many a convincing argument in favour of Free Trade, though in reality it had nothing to do with that question. But at what cost have these operations been made on India? Simply at this, that, whilst destroying the native manufacture, we have also curtailed the production of the raw material. Of the rapid diminution in its amount let the following figures tell: —

IMPORT OF COTTON FROM INDIA TO ENGLAND.

But raw material we must have, else our machinery is of no use. We have had so long a monopoly of cotton-spinning that we have accustomed ourselves, spite of nature, and spite of fact, to believe that our whole destiny was that of cotton-spinning. We ignore all history in favour of that particular shrub; and, pinning our faith to export tables – concocted by the weakest and most contemptible of charlatans – we make no hesitation in avowing that the prosperity and destiny of Great Britain is indissolubly entwined with our monopoly of cotton twist! That would be simply laughable, if we had not absolutely legislated on, and committed ourselves to that theory. We stand just now, in the face both of Europe and America – we know not whether we ought to exclude the other quarters of the globe – in the most ridiculous possible position. Our economists are permitted to say to them – "Send us your raw material, and we shall be proud and happy to work it up for you. Don't be at the pains or the cost of rearing manufactories for yourselves. That would entail upon you, not only a great deal of trouble, but a vast expenditure of capital, which you had much better lay out in improving your extra soil, and in bringing it to good cultivation. We can promise you a ready market here. Our proprietors and farmers are unquestionably heavily burdened by taxation, but they must submit to the popular will; or, if they choose to dissent, they may sell off their stock and emigrate to your country, where doubtless they will prove valuable acquisitions. You, we are well aware, are able to provide us with food cheaper than they can do it; and cheapness is all we look to. We shall even do more for you. We agree to admit to our market, at merely nominal duties, all your small articles of manufacture. You may undersell and annihilate, if you can, our glovers, hatters, shoemakers, glass-blowers, and fifty others – only do not interfere with the larger branches, and, above all, do not touch our monopoly of cotton."

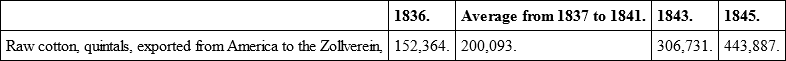

It is now obvious, and we believe generally acknowledged by those who have most practical knowledge of the subject, that the monopoly is broken up. America is seriously addressing herself to the task of applying her lately discovered stores of coal and iron to practical use; and, as we shall presently have occasion to show, she has no need to train workmen for that purpose, since the great emigration from this country supplies her with practised hands. That her rivalry will be of the most formidable description there can be no matter of doubt, for she will still be able to retain command of the raw material, and, retaining that, to regulate the price of cotton and cotton goods at New Orleans, instead of permitting Liverpool or Manchester to dictate authoritatively to the world. Whether the Manchester Chamber, finding their last move utterly abortive in securing monopoly, may succeed in rearing up plantations of cotton elsewhere than in America, is a point upon which we cannot speak with any degree of certainty. That they are alarmed, and deeply alarmed, at the prospect before them is evident, not only from the representations made in Parliament, and the desponding tone of their organs, but from the experiments which they have instituted for the purpose of ascertaining whether some other vegetable product may not be used as a substitute for cotton. Even if they were successful in one or other, or in both of their inquiries, it seems clear to us that they never can hope to regain their former ascendency. They must be exposed to the competition not only of America, but of the Confederation of the Zollverein, which now receives from the United States a large and increasing supply of raw material. The following table will show the extreme rapidity in the growth of that consumption: —

Although it never can be agreeable to know that any important branch of trade in this country is retrograding or falling into decay, we cannot affect to feel much sympathy with the cotton manufacturers, and that for several reasons. In the first place, their trade was a factitious one, not founded upon or tending in any degree to promote the real production of Great Britain, but avowedly rendering us dependant to a dangerous degree upon foreign supplies. Secondly, there can be no doubt that our demand for the raw material has had the effect of perpetuating slavery in the southern states of America. And, lastly, we cannot forget that we owe all our present difficulties to the machinations of men connected with the cotton manufacture. The doctrine that the strength of Britain lay in its powers of conversion, not in its powers of production, originated with them; and in their selfish eagerness to maintain a monopoly, even then in a precarious position, they made no scruple of sacrificing every interest which stood in their way. Our readers cannot fall to recollect the arguments which were employed by the champions and leaders of the League. America, whether as an example or an ally, was never out of their mouths. We were to spin for America, weave for America, do everything in short for her which the power of machinery could achieve. America, on the other hand, was to forego all idea of interfering with our industrial pursuits, in the way of encouraging her own children to become manufacturing rivals, and was to apply herself solely to the production of raw material, cotton, corn and provisions, wherewith the whole of us were to be fed. Our statesmen acted on this faith, assured us that we had but to show the example, and reciprocity must immediately be established, and opened the British ports without any condition whatever. The consequence was an influx of corn and provisions far greater than they expected, which at once annihilated agricultural profits in Great Britain, and is rapidly annihilating agriculture itself in Ireland. We were told to take comfort, because the very amount of the importations showed that it could not be continued; and yet it is continued up to the present day, and prices remain at a point which, even according to the estimate of the Free-traders, is not only unremunerative, but so injurious to the grower that he must lose by the process of cultivation. The actual labourer was the last sufferer, but he is suffering now, and his future prospects are most miserable and revolting. The smaller branches of manufacture, and the multitudes of artisans employed in these, have felt grievously the effect of lowered tariffs, and, even still more, the competition which has been engendered by the amount of displaced labour. Our large towns are the natural receptacles for those who have been driven from the villages, on account of sheer lack of employment; and ever and anon philanthropists are made to shudder by the tales of woe, and want, and fearful deprivation, which are forced upon the public ear. And yet few of them appear to have traced the evil to its source, which lies simply in the legislative discouragement of production, for the sake of a system of conversion which can offer no means adequate to the wants and numbers of the competing population.