полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 56, Number 350, December 1844

"It is evident that if the small notes issued in Scotland should be current beyond the Border, they would have the effect, in proportion as their circulation should extend itself, of displacing the specie, and even in some degree the local currency of England. Such an interference with the system established for England would be a manifest and gross injustice to the bankers of this part of the empire. If it should take place, and it should be found impossible to frame a law consistent with sound and just principles of legislation, effectually restricting the circulation of Scotch notes within the limits of Scotland, there will be, in the opinion of your committee, no alternative but the extension to Scotland of the principle which the legislature has determined to apply to this country.

"The other circumstances to which your committee meant to refer, as bearing materially upon their present decision, will arise in the event of a considerable increase in the crime of forgery. Your committee called for returns of the number of prosecutions and convictions for forgery, and the offence of passing forged notes, during the last twenty years in Scotland, which returns will be found in the appendix. There appears to have been, during that period, no prosecutions for the crime of forgery; to have been eighty-six prosecutions for the offence of issuing forged promissory notes – fifty-two convictions; and eight instances in which the capital sentence of the law has been carried into effect."

This may, on the whole, be considered as an impartial report; and, as it is as well in every case to disencumber a question from specialties, we shall state here that experience has since shown that there has been no tendency whatever to the introduction of Scottish notes into England. With regard to the other special point referred to by the committee – that of forgery – such a thing as a forged bank-note is now unknown in Scotland. The evidence taken before the last committee on banks of issue in 1841, established the fact, that since the improved steel plates were brought into general use, there has never been a forgery of a note. Such being the case, it is unnecessary here to dispute the wisdom of that policy which would leave a great national institution at the mercy of a single forger. The experience of this last month alone might show how wretchedly that test would operate if applied even to the Bank of England.

Setting these specialties aside, the only possibly grounds which this committee saw for any future legislative interference were, "the increasing wealth and commerce of Scotland, the rapid extension of her commercial intercourse with England, and the circumstances which may affect that intercourse after the re-establishment of an English metallic currency." To us the first part of this reservation sounds somewhat like a threat of future bleeding when Scotland shall have become more pursy and plethoric. Nevertheless we are ready to join issue with our opponents on any of these grounds.

The report of the Lords was even more favourable; and, at the risk of being thought tedious, we cannot refrain from inserting their admirable digest of the evidence, which, for candour and clearness, might be taken as a universal model.

"With respect to Scotland, it is to be remarked, that during the period from 1766 to 1797, when no small notes were by law issuable in England, the portion of the currency in Scotland in which payments under five pounds were made, continued to consist almost entirely of notes of £1 and £1, 1s.; and that no inconvenience is known to have resulted from this difference in the currency of the two countries. This circumstance, amongst others, tends to prove that uniformity, however desirable, is not indispensably necessary. It is also proved, by the evidence and by the documents, that the banks of Scotland, whether chartered or joint-stock companies or private establishments, have for more than a century exhibited a stability which the committee believe to be unexampled in the history of banking; that they supported themselves from 1797 to 1812 without any protection from the restriction by which the Bank of England and that of Ireland were relieved from cash payments; that there was little demand for gold during the late embarrassments in the circulation; and that, in the whole period of their establishment, there are not more than two or three instances of bankruptcy. As, during the whole of this period, a large portion of their issues consisted almost entirely of notes not exceeding £1 or £1, 1s., there is the strongest reason for concluding, that, as far as respects the banks of Scotland, the issue of paper of that description has been found compatible with the highest degree of solidity; and that there is not, therefore, while they are conducted upon their present system, sufficient ground for proposing any alteration, with the view of adding to a solidity which has been so long sufficiently established.

"This solidity appears to derive a great support from the constant exchange of notes between the different banks, by which they become checks upon each other, and by which any over-issue is subject to immediate observation and correction.

"There is also one part of the system, which is stated by all the witnesses (in the opinion of the committee very justly stated) to have had the best effects upon the people of Scotland, and particularly upon the middling and poorer classes of society, in producing and encouraging habits of frugality and industry. The practice referred to is that of cash-credits. Any person who applies to a bank for a cash-credit is called upon to produce two or more competent securities, who are jointly bound, and after a full enquiry into the character of the applicant, the nature of his business, and the sufficiency of his securities, he is allowed to open a credit, and to draw upon the bank for the whole of its amount, or for such part as his daily transactions may require. To the credit of this account he pays in such sums as he may not have occasion to use, and interest is charged or credited upon the daily balance, as the case may be. From the facility which these cash-credits give to all the small transactions of the country, and from the opportunities which they afford to persons who begin business with little or no capital but their character, to employ profitably the minutest products of their industry, it cannot be doubted that the most important advantages are derived to the whole community. The advantage to the banks who give those cash-credits arises from the call which they continually produce for the issue of their paper, and from the opportunity which they afford for the profitable employment of part of their deposits. The banks are indeed so sensible that, in order to make this part of their business advantageous and secure, it is necessary that their cash-credits should (as they express it) be frequently operated upon, that they refuse to continue them unless this implied condition be fulfilled. The total amount of their cash-credits is stated by one witness to be five millions, on which the average amount advanced by the banks may be one-third.

"The manner in which the practice of deposits on receipt is conducted tends to produce the same desirable results. Sums to as low an amount as £10 (and in some instances lower) are taken by the banks from the depositor, who may claim them at demand. He receives an interest, usually about one per cent below the market rate. It is stated that these deposits are, to a great extent, left uncalled for from year to year, and that the depositors are in the habit of adding, at the end of each year, to the interest then accrued, the amount of their yearly savings; that the sums thus gradually accumulated belong chiefly to the labouring and industrious classes of the community; and that, when such accounts are closed, it is generally for the purpose of enabling the depositors either to purchase a house or to engage in business.

"It is contended by all the persons engaged in banking in Scotland, that the issue of one-pound notes is essential to the continuance both of their cash-credits and of the branch banks established in the poorest and most remote districts. Whether the discontinuance of one-pound notes would necessarily operate to the full extent which they apprehend, in either of these respects, may perhaps admit of doubt; but the apprehensions entertained on this head, by the persons most immediately concerned, might, for a time at least, have nearly the same effect as the actual necessity; and there is strong reason to believe, that if the prohibition of one-pound notes should not ultimately overturn the whole system, it must for a considerable time materially affect it.

"The directors of the Bank of England, who have been examined before the committee, have given it as their opinion, that a circulation of notes of £1 in Scotland or in Ireland would not produce any effects injurious to the metallic circulation of England, provided such notes be respectively confined within the boundary of their own country.

"Notwithstanding the opinions which have been here detailed, the committee are, on the whole, so deeply impressed with the importance of a metallic circulation below £5 in England, not only for the benefit of England, but likewise for that of all the other parts of the empire, that if they were reduced to make an option between the establishment of such a metallic circulation in Scotland, or the abandonment of it in England, they would recommend the prohibition of small notes in Scotland. But they entertain a reasonable expectation, that legislative measures may be devised which will be effectual in preventing the introduction of Scotch paper into England; and unless such measures should in practice prove ineffectual, or unless some new circumstance should arise to derange the operations of the existing system in Scotland itself, or materially to affect the relations of trade and intercourse between Scotland and England, they are not disposed to recommend that the existing system of banking and currency in Scotland should be disturbed."

This is just what a Parliamentary report ought to be – calm, perspicuous, and decided. There is no circumlocution nor ambiguity of expression here. After a patient investigation into the whole question, and a minute examination of enemies as well as friends, the Lords arrived at the opinion, that the existing banking system of Scotland ought on all points to be maintained, and they not only stated their general conviction, but gave their reasons for upholding each part in detail, in the luminous manner which has always been the characteristic of that august Assembly, and which has established its proud reputation as not only the noblest, but the most upright tribunal of the world. It is worthy of the most marked attention, that the committee of the Lords in this report, which afterwards received the sanction of the House, advocated no temporary continuance of the banking system in Scotland, but were clearly of opinion that it should remain as a permanent institution. They evidently entertained no ideas, grounded upon mere expediency, that it would be prudent to wait until Scotland, by means of her cherished institutions and her own internal industry, arrived at that point of condition when it might be expedient to introduce the lancet, and drain off a little of her superfluous blood. They vent upon the righteous maxim – that a nation, as well as a man, is entitled to work out its own resources in peace, so long as it does not trench upon the industry or prerogatives of its neighbour, and so long as no impeachment can be laid against the prudence and stability of its institutions. We defy any man to read over this report, and to adduce one word from it which shall convey the idea that it was not intended as a final judgment, with the simple qualifications that we have stated in the last sentence.

These two reports saved the country – we trust we shall not hereafter be compelled to add, only for a time – from its great impending misfortune. The circulation in England became metallic, with what success it is not for us to say, whilst Scotland was allowed to retain her paper currency with at least most perfect satisfaction to herself. One pregnant fact, however, it would be unpardonable for us to omit – as showing the stability of the northern system when compared with that practised in the south – that at the last investigation before a committee of the House of Commons in 1841, it was stated, that whereas in Scotland the whole loss sustained by the public from bank failures, for a century and a half, amounted to L. 32,000, the loss to the public, during the previous year in London alone, was estimated at ten times that amount!

Since 1826, we have had eighteen years' further experience of the system, without either detecting derangement in its organization, or the slightest diminution of confidence on the part of the public. There has been no interference with the metallic currency of England. Forgery is a crime now utterly unknown, as is also coining, beyond the insignificant counterfeits of the silver issue. This, in fact, is a great advantage which we have above the English in point of security, since we are exempt from the risk of receiving into circulation either base or light sovereigns, and since the banks provide for the deterioration of their notes by tear and wear, whilst the holder of a light sovereign has to pay the difference between the standard and the deficient weight. When we reflect upon the small amount of the wages of a labouring man, it is manifest how important this branch of the subject is; for were gold allowed in Scotland to supersede the paper currency, a fresh and most dangerous impetus would be given to the crime of coining; and there cannot be a doubt, that in the remoter districts, where gold is utterly unknown, a most lamentable series of frauds would be perpetrated, with little risk of detection, but with the cruelest consequences to the poor and illiterate classes.

We are not, however, inclined to adopt the opinion expressed by the committee of the House of Commons, to the extent of admitting that it would be either politic or just to disturb the whole banking system of a country on account of private frauds, whether forgeries or the fabrication of counterfeit coin. If their opinion was a sound one, the weight of evidence is now upon our side of the argument; but we hold that the interests at stake are far too great to be affected by any such minor details. If any new circumstance has arisen "to affect the relations of trade and intercourse between Scotland and England," we at least are wholly unconscious of the occurrence, and, of course, it is the duty of those who meditate a change to point it out, in order that it may be thoroughly scrutinized. Internally, the business of the banks has been increasing, and, commensurate with that increase, there has been a vast addition to the number of branch banks spread over the face of the country; so that, whereas in 1825 there was but one office for every 13,170 individuals, in 1841 there was an office for every 6600 of the population. This is plainly the inevitable effect of competition; but lest that increase should be founded upon by our opponents as a proof of over-circulation, we shall say a few words upon the subject of the exchange between the banks themselves, which is a leading feature of our whole system, and the most complete check against over-trading which human ingenuity could devise. Fortunately we have ample data for our statement in the evidence tendered to the committee on banks of issue in 1841.

It is right, however, to premise that, strictly speaking, there are not more, nay, there are positively fewer banks in Scotland at the present moment than there were in 1825, though the amount of paid-up capital in the banks is more than doubled. It is the branches alone which make this astonishing increase. Now, as a branch is merely a local agency of the parent bank, established at a distance for the sake of outlying business, the number of parties engaged in banking who are responsible to the public is not thereby increased, nor is the amount in circulation extended. In fact, the multiplication of the branch banks has been of extraordinary benefit to the public, by affording the inhabitants of even the remotest districts a ready, easy, and favourite method of deposit, and by extinguishing all risks of credit. Further, it has this manifest advantage, that the manager of the branch bank has far greater facilities of ascertaining the character, habits, and pursuits of those persons who may have received the advantage of a cash-credit accommodation, and can immediately report to his superiors any circumstances which may render it advisable that the credit should be contracted or withdrawn. So far are we from holding that the multiplication of branch banks is any evil or incumbrance, that we look upon it as an increased security not only to the banker but the dealer. The latter, in fact, is the principal gainer; because a competition among the banks has always the effect of heightening the rate of interest given upon deposits, and of lowering the rates charged upon advances. Nor does this give any impetus to rash speculation on the part of the dealer, but directly the reverse. The deposits always increase with the advancing rate of interest; and experience has shown, that it is not until that rate declines to two per cent that deposited money is usually withdrawn, which is the signal of commencing speculation. To the mere speculator the banks afford no facilities, but the reverse. Their cash credits are only granted for the daily operations of persons actively engaged in trade, business, or commerce. So soon as that credit appears to be converted into a different channel, it is withdrawn, as alike dangerous to the user and unprofitable to the bank which has given it.

Of thirty-one banks in Scotland which issue notes, five only are chartered– that is, the responsibility of the proprietors in those established is confined to the amount of their subscribed capital. The remaining twenty-six are, with one or two exceptions, joint-stock banks, and the proprietors are liable to the public for the whole of the bank responsibilities to the last shilling of their private fortunes. The number of persons connected with these banks as shareholders is very great, almost every man of opulence in the country being a holder of stock to a greater or a less amount. That some jealousy must exist among so many competitors in a limited field, is an obvious matter of inference. Such jealousy, however, has only operated for the advantage of the public, by the maintenance of a common and vigilant watch upon the manner in which the affairs of each establishment are conducted, and against the intrusion of any new parties into the circle whose capital does not seem to warrant the likelihood of their ultimate stability. Accordingly, the Scottish bankers have arranged amongst themselves a mutual system of exchange, as stringent as if it had the force of statute, by means of which an over-issue of notes becomes a matter of perfect impossibility. Twice in every week the whole notes deposited with the different bank offices in Scotland are regularly interchanged. Now, with this system in operation, it is perfectly ludicrous to suppose that any bank would issue its paper rashly for the sake of an extended circulation. The whole notes in circulation throughout Scotland return to their respective banks in a period averaging from ten to eleven days in urban, and from a fortnight to three weeks in rural districts. In consequence of the rate of interest allowed by the banks, no person has any inducement to keep bank paper by him, but the reverse, and the general practice of the country is to keep the circulation at as low a rate as possible. The numerous branch banks which are situated up and down the country, are the means of taking the notes of their neighbours out of the circle as speedily as possible. In this way it is not possible for the circulation to be more than what is absolutely necessary for the transactions of the country.

If, therefore, any bank had been so rash as to grant accommodation without proper security, merely for the sake of obtaining a circulation, in ten days, or a fortnight at the furthest, it is compelled to account with the other banks for every note they have received. If it does not hold enough of their paper to redeem its own upon exchange, it is compelled to pay the difference in exchequer bills, a certain amount of which every bank is bound by mutual agreement to hold, the fractional parts of each thousand pounds being payable in Bank of England notes or in gold. In this way over-trading, in so far as regards the issue of paper, is so effectually guarded and controlled, that it would puzzle Parliament, with all its conceded conventional wisdom, to devise any plan alike so simple and expeditious.

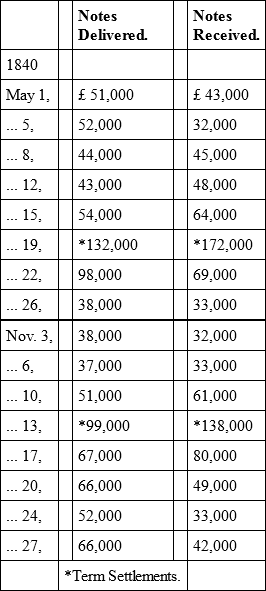

The amount of notes at present in circulation throughout Scotland is estimated at three millions, or at the very utmost three millions and a half. At certain times of the year, such as the great legal terms of Whitsunday and Martinmas, when money is universally paid over and received, there is, of course, a corresponding increase of issue for the moment which demands an extra supply of notes. It is never considered safe for a bank to have a smaller amount of notes in stock than the average amount which is out in circulation; so that the whole amount of bank-notes, both in circulation and in hand, may be calculated at seven millions. The fluctuation at the above terms is so remarkable, that we are tempted to give an account of the number of notes delivered and received by the bank of Scotland in exchange with other banks during the months of May and November 1840: —

It will be seen from the above table how rapidly the system of bank exchange absorbs the over-issue, and how instantaneously the paper drawn from one bank finds its way into the hands of another.

If further proof were required of the absurdity of the notion, that a paper circulation has a necessary tendency to over-issue, the following fact is conclusive. The banking capital in Scotland has more than doubled between the years 1825 and 1840 – a triumphant proof of their increased stability; whilst the circulation has been nearly stationary, but, if any thing, rather diminished than otherwise. We quote from a report to the Glasgow Chamber of Commerce.

"The first return of the circulation was made in Scotland in 1825. Every one knows the extraordinary advance which Scotland has made between that period and 1840; for instance, in the former of these years, she manufactured 55,000 bales of cotton, in the latter, 120,000 bales. In 1826, the produce of the iron furnaces was 33,500 tons; in 1840, about 250,000 tons. In 1826, the banking capital of Scotland was £4,900,000; in 1840, it was about £10,000,000; yet with all this progress in industry and wealth, the circulation of notes, which in 1825 varied from £3,400,000 to £4,700,000, was in 1839 from £2,960,000 to £3,670,000, and in the first three months of 1840, £2,940,000."

We are induced to dwell the more strongly upon these facts, because we have strong suspicions that our opponents will endeavour to get at our monetary system by raising the senseless cry of over-issue – senseless at any time as a political maxim, it being the grossest fallacy to maintain that an increased issue is the cause of national distress, unless, indeed, it were possible to suppose that bankers were madmen enough to dispense their paper without receiving a proper equivalent – not only senseless, but positively nefarious, when the clear broad fact stares them in the face, that Scotland has in fifteen years thrown double the amount of capital into its banking establishments, increased its productions in a threefold, and in some cases a sevenfold ratio, augmented its population by nearly half a million, (one-fifth part of the whole,) and yet kept its circulation so low as to exhibit an actual decrease.

If we were called upon to state the cause of this certainly singular fact, we should, without any hesitation, attribute it to the great increase of the bank branches. The establishment of a branch in a remote locality, has invariably, from the thrifty habits of the Scottish people, absorbed all the paper which otherwise would have been hoarded for a time, and left in the hands of the holders without any interest. It would thus seem, from practice, that the doctrines of the political economists upon this head are absolutely fallacious; that the increase of banks, supposing these banks to issue paper and to give interest on deposits, has a direct tendency to check over-circulation, and in fact does partially supersede it.