полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 71, No. 438, April 1852

Another authority, Messrs Littledale & Co., of Liverpool, remark upon this article as follows, in their circular of the 1st January: —

"Great indeed has been the disappointment during the past year of importers and holders of nearly every description of produce; but to no parties has it been so severe as to those interested in the article of sugar, cotton excepted. The year 1851 opened with high prospects – moderate stocks, an average supply, and a largely increased consumption, arising from the satisfactory condition of the manufacturing districts, and the great prospects which were generally entertained of the approaching Exhibition; but these hopes were soon dissipated, the imports of foreign continuing on an unusually large scale, and the consumption, instead of increasing, barely supporting that of the previous year. The increased production of sugar from beetroot on the Continent is fast displacing all foreign, and the latter, in turn, displacing our colonial, or forcing it down to so low a figure that its production will be unremunerative. In little more than two years the duties will be equalised; and we can see no salvation for our colonies but a complete change, both in the manufacture and curing of this article, as it is quite evident that the taste of the large consumers in the country is changing year by year more in favour of crushed refined… The decline in the value of sugar throughout the past year has been gradual, though marked; and prices now rule 5s. to 6s. per cwt. lower on better descriptions, and 8s. to 10s. on the common and low brown sorts."

With respect, then, to that portion of the supply of sugar derived from the West Indies, the only question which can arise is – Can the grower have succeeded during the past year in reducing the cost of production so far as to have allowed the Gazette average of British plantation to fall from 29s. 2d. nett in February of last year, to 20s. 2d. in the February of this year? We know that during this period no economising of labour has been achieved to warrant a decline of 9s. per cwt. – nearly thirty per cent; and the conclusion is obvious, that the bulk of this saying to the British consumer has come out of the pockets of the colonial proprietor and the British colonial merchant. The price at the commencement of the year, it is admitted, was a barely remunerative one; and every shilling of reduction since has been positive loss.

With respect to East India sugar, which is actually purchased in the country of its growth, the loss has fallen directly upon the importer – the fact being notorious, that prices throughout the year have ruled higher in the colonial markets, and in China, Java, &c., by from 4s. to 5s. per cwt. than it could be sold for on its arrival here. Messrs Littledale & Co. quote the prices of Bengal, Madras, and Mauritius, best and good descriptions, in bond, from 6s. to 6s. 6d. lower in January this year than in January last year, and common and inferior descriptions as much as 8s. to 9s. lower. Upon China and Manilla the fall has been from 3s. to 4s. 6d.

The same authority to which I have before referred – the New London Price Current– remarks of Mauritius sugar, that the "rates are 5s. to 8s. per cwt. lower, the difference being most apparent on brown and inferior qualities;" and of East India, "Stock is 6950, (in London,) and in 1850 it was 5500 tons. Prices range 4s. to 8s. per cwt. under that period, the difference being more apparent on brown and inferior qualities, of which there is a loss upon importation."

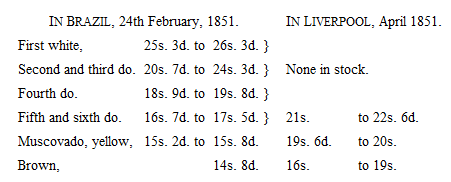

With respect to foreign sugar, a few preliminary explanations are necessary. As is the case with East India produce, the sugar which we draw from foreign countries – the bulk from Cuba and the Brazils – is purchased by British merchants at a price in the country of its growth, regulated of course by the cost of production, and the probable market price in Great Britain. The foreign planter, however, is seldom more than a nominal proprietor, working with borrowed capital, for which he pays an interest of from fifteen to twenty per cent, and living, in all respects, only like a superior servant or agent. With the question, whether of late he has been enabled to reap a profit on his cultivation, I have here nothing to do, although it is most probable that he has not done so, even at the prices which he has been able to secure from the British purchaser. He has had labour foisted upon him beyond his requirements, and at an exorbitant price, the slave-dealer being in many cases the party supplying capital for sugar cultivation, and the virtual proprietor of the soil and stock. So far as regards the operations of British merchants in the produce of Brazil, Cuba, and other foreign tropical produce, the result has been almost equally disastrous with that attending the trade with our own possessions. Prices in these countries have, throughout nearly the whole of the past year, been from 3s. to 5s. above those which could be realised in this country; and the loss upon the entire importation has been little, if at all, less than that upon British colonial produce. The London New Price-Current sums up its remarks upon the trade in foreign sugar by saying, – "Prices, compared with this date last season, exhibit a decline of 3s. on the better, and 4s. to 6s. per cwt. on the brown and inferior qualities." A comparison of the prices in the country of production, with those realised here, will prove this part of my case. From the Pernambuco Price Current, of the 24th of February 1851, I find that the following were the prices of Brazilian sugar, free on board; and I have set opposite to the figures the price which it would command in bond, on its arrival here, as furnished by one of our leading brokers: —

The first qualities of the above are not imported into this market; and adding to the other, for freight at 60s. per ton, 3s. – buyer's commission in Brazil, 3 per cent – insurance, interest, brokerage, and other charges, say 4s. 6d. to 5s. per cwt. – there would be a small loss upon the importation.

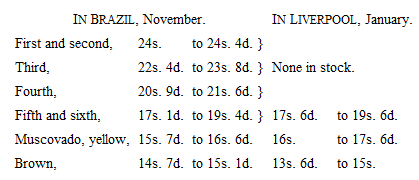

I select a later date, in order to ascertain the cost of the stocks on hand at the commencement of this year. On the 29th November last the quotations were —

At this period freights ruled low, 35s. to 40s.; and, as is always the case when there is an abundance of shipping seeking cargo, the foreigner advanced his rates for produce. Adding 3s. 6d. to 4s. for charges upon imports, there would be a loss of, say 3s. 6d. to 5s. 6d. upon white; 3s. 6d. upon yellow; 5s. 6d. upon low brown, and 3s. 6d. upon the better quality. The same result is found to have resulted upon Cuban and other foreign sugars.

The reduction in this article has not been so sudden as to entitle us to put down more than a portion of it as loss to either importer or producer. Bearing in mind, however, that, from the commencement of the year to the close, it has been arriving in this country at a cost considerably over what it would realise, and that we had a good stock to begin the year with, which has kept accumulating, I believe I am justified in assuming the result of the year's business to be a loss, upon the whole of our sugar imports, of at least £5 per ton; which, upon 400,000 tons of all descriptions, amounts to the sum of £2,000,000 sterling. In this I am borne out by some of our leading authorities, whose names I hand you for your own satisfaction. Having in this calculation merged the stock in hand at the commencement of the year, (107,000 tons,) which was imported at extreme prices, and lost much more than I have taken as an average, it is but fair to add something for the depreciation of the increase of stock held at the close of the year, 50,000 tons, (the total stock having been 157,000 tons against 107,000 at the commencement.) If I estimate this depreciation at £3 per ton – it fell nearly £1 in the beginning of January, and has since been quoted lower – I am satisfied that I am within the mark. This will make the total loss on sugar £2,150,000 sterling.

In the important article of Coffee there has also been a serious loss upon the year's transactions; and this notwithstanding the fact that the import was lighter in 1851 than in either of the two preceding years, having been 22,100 tons of all descriptions against 22,700 in 1850, and 27,000 in 1849. The prices at the close of the year are stated by the London New Price-Current to have been "from 8s. to 16s. per cwt. below this date last season." Messrs Littledale's annual circular shows a fall, in "native ordinary Ceylon" of 16s., and of 15s. in "middling plantation." The fall is less in some of the scarcer sorts. The greatest reduction, however, was in the middle of the year, "good ordinary native Ceylon," which was worth 57s. per cwt. in January, having fallen to 37s. in June. The total loss to importers, I am advised, cannot be estimated at less than £10 per ton, which, upon the total import of 22,100 tons, makes up an amount of £221,000 sterling. It is worth while remarking here, as an instance of the blindness of Whig legislation, that although the duties on coffee were reduced last year from 6d. on foreign, and 4d. on colonial, to a uniform rate of 3d., to the serious injury of colonial interests, and apparently with no other object in view, the consumption was very little increased, having been 31,226,840 lb. in 1850, and only 32,564,164 lb. in 1851. The actual vend by retailers of what is called coffee– the adulterated article – is, however, known to have largely increased; and the grocer and fraudulent dealer, by the use of chicory, the admixture of which with coffee the Chancellor of the Exchequer refused to restrict, and of other worse ingredients, have been enabled to put far more than the amount of the duty remitted into their own pockets. The stock held over from 1850 was 19,300 tons; and as this was very little reduced in December 1851, and the bulk of it was bought at even higher prices than those ruling at the commencement of the year, it will not be unfair to estimate the loss upon it at £10 per ton, the same as that upon the importations. I will, however, assume it to have been only, in round numbers, £150,000. This will make the total loss on coffee £371,000.

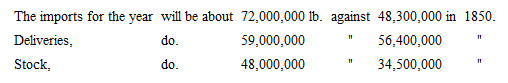

In another important article – Tea – there have been very heavy losses. We commenced the year with prices of congou, the leading article of black tea, at 1s. to 1s. 0½d. for "ordinary to good ordinary," and better sorts proportionally higher. The year closed with the same teas at 8d. to 8½d., and a proportionate fall in other descriptions of black. In some sorts of green there has not been so great a fall; but upon all kinds (two excepted, of which the consumption is not large) I find the decline estimated by Messrs Littledale & Co. at 25 to 35 per cent. The fall per lb. may, with tolerable safety, be set down at 4d. It has not been so gradual as in the case of other descriptions of produce, having, on the contrary, occurred rather suddenly towards the middle and close of the season; and this fact has an important bearing upon the amount actually lost by importers. In the first four months of the year prices gave way a little; but the demand was good, and no serious disaster in the trade was expected. Imports, however, flowed in freely, beyond the requirements for consumption; and the new crop arriving unusually early by the clipper ships, now engaged between this country and China, a sort of panic ensued, and reductions of 2d. to 4d. per lb. were submitted to. With a view to render my calculations with regard to this article perfectly intelligible, I subjoin the state of imports, stock, and consumption, as given in Messrs Littledale's Circular of Jan. 3: —

Thus, although the deliveries in 1851 exceeded those of 1850, there was an increased stock, caused by the unusually early arrival of the new crop. Under these circumstances, I find that I am fully justified in taking the loss upon the entire imports at 2d. per lb., which, upon 72,000,000 lb., will be £600,000. The stock on hand at the commencement of the year, 34,500,000 lb., may be estimated as having lost 4d. per lb., or £575,000, leaving in its place an accumulation of 48,000,000 lb. at the close of the year, upon most of which there is a farther loss upon the price at which it was imported, even assuming that it was well bought, according to the range of prices here in November and December, when the bulk of the new crop reached us. I do not take into account, however, any loss upon this stock, or even upon its excess over that of the preceding year; and only set down the result as above, at a total loss of £1,175,000 for the year.

Even in the import of Foreign Grain the transactions of the year have been of a most unsatisfactory character, and the general result has been a loss, estimated at a very moderate computation to amount to, at the least, £500,000. The whole of this, however, has not fallen directlyi upon British merchants, who are regularly engaged in the trade, but in part upon foreign houses; and upon speculators who, having been misled by the miscalculations of the Free-Trade press, and by an over-sanguine temperament, to anticipate a considerable revival of prices during the close of 1850 and the beginning of 1851, were induced to become holders of the article. In the most favourable cases, however, up to the slight revival which took place at the close of the past year, the importer has been unable to secure more than a bare brokerage, except upon French flour; and taking every redeeming circumstance into consideration, I am warranted in setting down the loss of the year at £500,000, as above stated.

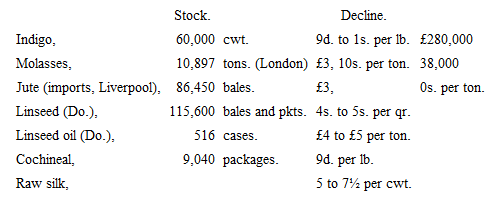

Upon a number of other important articles, the loss has been very heavy throughout the year, both to importers and holders of stock. Amongst these, I may mention many kinds of American provisions, colonial molasses, silk, indigo, jute, hides, linseed, and other seeds, linseed oil, gums, madder roots, dyes, dye-woods, spices, foreign fruits, &c. I shall only trouble your readers with a few, and give, in doing so, the stock and total decline during the year, not being able to give the aggregate loss in detail: —

On dye-woods the loss has been fearful, cargoes imported having in many cases not realised more than actual freights; and foreign fruits have been a drug throughout the year, and have perished, or else been sold at ruinous reductions from import cost. The total loss upon the import of these articles, added to what I have already estimated, will make up a gross amount of ten millions sterling.

I have already stated that, in addition to the loss in first hands, there must have been a very serious one sustained by manufacturers, dealers, and retailers, throughout the country. In all cases of falling markets of either raw materials or produce, the cheaper import presses upon previously made purchases, and compels a sacrifice of a portion of stock in hand. The manufacturer who is consuming cotton bought at 7d. per lb., finds, when he has converted the raw material into goods, that he has to compete with his neighbour, who is willing to make a contract for the same article with cotton at 6d. per lb. The calico printer and dyer finds a competitor who has bought his dyes ten per cent below him. The grocer and tea-dealer has in the same way to accommodate his prices to those which happen to rule in the wholesale market. With respect to the cotton manufacturer, we have been told that his business has been satisfactory; that he had made contracts in advance, which paid him a profit upon the raw material purchased for the purpose of fulfilling them. Suppose this to have been the case, which is only partially so, the loss must have fallen upon the buyer, who would have to take his goods into the home or the foreign market, in competition with more recent and cheaper purchases. Every speculative holder of produce, and every dealer, must have been similarly affected. I conceive, then, that I am not exaggerating the loss sustained by these parties, by estimating it at one-fifth of that which I have traced to importers, and adding another two millions sterling to the previous amount of ten millions.

And now, let me ask, at what are we to estimate the loss sustained by the shipping interest during the past year?

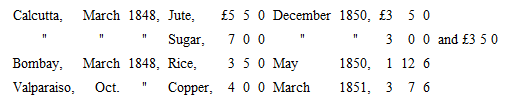

The amount of British tonnage entered inwards during the year ended 5th January 1852 was 4,388,245 tons, against 4,078,544 tons in the preceding year; the entries outwards were 4,147,007 tons against 3,960,764 tons; making a total, inwards and outwards, of 8,535,252 tons in 1851, against 8,039,308 in 1850 – an increase of 495,944 tons. I refer to these returns with a view to base upon them my estimate of loss sustained; and certainly am not inclined to follow those superficial observers who are in the habit of taking the increase of tonnage, shown by them from time to time, as evidence of increased prosperity of the shipowner. It is well known that our steamers engaged in the foreign trade have enormously swelled the entries, both inwards and outwards, during the last two years. From this port alone we have now a fleet of five vessels of 300 tons and upwards, making fortnightly and monthly trips to the North of Europe and the Mediterranean, each trip of which counts for as much in the entries as the long voyage of a sailing vessel. The Cunard Line to the United States has been augmented; and we are establishing other lines to the Brazils, to Australia, &c. Our West Indian and Oriental Fleets have been similarly augmented. As a further cause of the apparent increase of sailing tonnage, the more rapid passages made by vessels of the clipper build may be mentioned – some of which, it is well known, have during the past year made the voyage out and home to China, the East Indies, &c., in from eight to ten months; whereas ships of the ordinary build and rig would have occupied above twelve months, and thus have come once only, instead of twice, into the returns. Deducting the steam and clipper ships, a correct return would, I believe, show a decrease instead of an increase in our mercantile marine; for it is well known that a large amount of British tonnage has during the past three years been rotting in the waters of California. Far better would it have been for some of the remainder, if, instead of contributing to swell these returns with a tale of delusive prosperity, it could have been laid up in dock, saving the cost of unprofitable wear and tear and of wages. But our New Navigation Laws have rendered such a course of no avail to the British shipowner. If a portion of our mercantile navy had been laid up for a time, the foreigner would have promptly assumed its place, and benefited by the advance in freights which would have resulted from competition being withdrawn. As it is, during the whole of the past year, the British shipowner, in carrying on the struggle which has been forced upon him by our Free-Trade policy, has been injuriously met by this competition in every foreign port, and especially in the ports of our Eastern possessions and their dependencies, the carrying trade of which, formerly secured to the shipping of this country, afforded such a valuable source of remuneration to the British shipowner. In the ports of China we have been met with the same depressing competition. There is not, in fact, a country on the surface of the globe to which a ship could be sent, in cargo or in ballast, with any certainty of earning a return freight which would pay even ordinary expenses of wages and port-dues – necessary repairs being out of the question. In the attempt, which I propose to make, to form an estimate of the losses sustained upon shipping during the past year, it must be borne in mind that the year 1850, with which I shall have to compare it, was notoriously one of severe suffering to all parties interested in shipping. We had then begun to feel the effects of the ruinous policy upon which we had embarked; and the amount of loss sustained in that year had been previously unparalleled in the annals of our commerce. There was a decline, for example, of the rates current in 1848, of the extent of which the following figures, taken from the June number of Blackwood, furnishes a correct idea. The figures in question, I may remark, were based upon actual transactions: —

Other freights bore a similar ratio of decrease. During the past and present year we have had sugar brought from Calcutta at as low as 30s. per ton, and cotton from Bombay at £2, 5s. From China we have had tea as low as 40s.; whereas, in 1850, "The Oriental," American clipper, got £6 per ton, an ordinary British ship being able to command about £4. From the west coast of America we have lately had guano brought to this country for as low as 30s. to 40s. per ton. In March last the freight actually realised was £3, 12s. per ton. These, however, it will be said, are extreme cases. I give, therefore, a more general statement, although it is almost impossible to arrive at a fixed rate of freights for any portion of our long-voyage trade. Throughout the whole of our Eastern ports, and of China, as well as in the ports of the west coast of America, the rates have depended, as they did in 1850, upon the number of American vessels arriving in ballast from round Cape Horn in search of freight, after having earned a very ample remuneration from their previous voyage from the Atlantic ports of the United States – a voyage in the benefits of which British shipping is not allowed to participate; – and these have been most arbitrary and uncertain in amount. As a rule, I find that I may safely put down the long-voyage freights, both from the East and West, as having fallen 30 per cent during the past twelve months. This is the case even with regular traders; and with transient ships it is much more. With respect to Mediterranean and other European freights, the reduction is over 10 per cent for British vessels. In Canadian timber freights there has been an average fall to large ports of from 33s. to 30s. per load in 1850, to about 25s. in 1851. With respect to these ships, the bulk of the tonnage is taken up by timber-importers, some of whom are also owners; and the result of the voyage, so far as the profit to the ship is concerned, is mixed up with the result of the sale of the freight. The Australian voyage has been a set-off against the general loss on shipping. Emigrants and goods for these settlements have been in abundance, but ships' expenses have been increased. Only for great and costly precautions, these settlements threaten to be the grave of as large an amount of shipping as that which is now rotting idle in the waters of San Francisco.

In endeavouring to arrive at an estimate of the gross amount of loss to British shipping during the past year, I avail myself of a calculation made by a gentleman who occupies the position of secretary to the Underwriters' Association – the Lloyd's – of Liverpool. In an estimate of the amount to be put down as the freight paid to British shipowners upon the imports of 1850, that gentleman considered that a fair average earning of freight upon long and short voyages would be £2 per register ton. The total entries inwards of 1851 have been 4,388,245 tons, the freight upon which, at the estimated rate of the year 1850, would have been thus, in round numbers, £8,776,490. Bearing in mind that a large portion of British shipping goes out in ballast, and that the earnings outwards are considerably less at all times than inwards, I shall not estimate the outward freight in 1850 at more than 25s. per register ton. Taking the tonnage outwards of 1851 – 4,147,007 tons – at this rate, the amount would be £5,183,750 – making a total, inwards and outwards, of, in round numbers, £13,900,000. I have already said, and shown from its antecedents, that the year 1850 was a year of heavy sacrifice of British shipping. It is much if the bulk of our shipping during that year earned more than would pay for necessarily-occurring repairs, which in many cases were postponed until better times – which were hoped for – should arrive. Taking all things into account – the actual reduction of freights, and the necessity which has accrued for executing those repairs – I cannot set down the loss to the British shipowner during the past year at less than 20 per cent upon his freight, or £2,700,000 sterling. In addition to the shipping engaged in the foreign trade, I have to estimate as well the loss sustained upon our coasting tonnage, which amounted, in 1851, to 12,394,902 tons inwards, and 13,466,155 tons outwards. Upon the earnings of this class of vessels there was a reduction, in 1850, of fully 30 per cent. In fact, during that year, it brought to the owners only loss and annoyance. During the past year it cannot be said that the freights earned have been materially reduced; but they have been earned only whilst the vessels were in rapid course of being thoroughly worn out, repairs bestowed upon them, being felt to be hopeless outlay. I take, as the basis of my calculation, a tonnage about half of the aggregate "inwards and outwards" – viz. 13,000,000; and estimate the freight both ways – and it is not much over the average of one way – at 5s. per ton. We have thus a gross amount of freight earned, of £3,250,000. I might treat the whole of this sum as absolute loss; for it is notorious that, as compared with former years' earnings, it is so. Not one in a hundred of our coasters are paying interest and wages. Cost of necessary repairs they do not pay; and, in fact, they are only sailed either in the fallacious hope of better days to come, or until they go to pieces, and are destined to be broken up for the timber and the copper and iron bolts which they contain. I shall only estimate them, therefore, at the probable amount of their deterioration, which cannot be less than £2,000,000, making a total loss upon British shipping of £4,700,000 sterling. This may appear an extreme amount of loss to those who do not take into consideration the peculiar nature of shipping property, its constant deterioration, and the large proportion which expenses upon it ordinarily bear to the freights earned. With respect to the estimate which I have made of the loss upon our coasters, it will probably be exclaimed against as very vague and incapable of being proved. It must be borne in mind, however, that this class of property has been injuriously affected by a combination of causes, some of which it is only fair to refer to, as, to a certain extent, removing it out of the scope of my general arguments. Our coasting vessels have had to encounter severe competition with steam craft, particularly with respect to the traffic in merchandise and produce capable of bearing the higher rates of freights. Our internal railway communications have also interfered seriously with their traffic coastwise. A considerable amount of our coal and iron carriage has been abstracted from the small vessels formerly employed by it. For example, I heard within the last few weeks, of a government contract for engine-coals from the northern coal-fields having been entered into, such coals to be laid down at one of our dockyards for a little over 16s. per ton per rail– if I remember right, the Great Northern. Still, much of the deterioration in this property is attributable to our new system, which virtually hands over a portion of our coasting trade to the foreign shipowner. Cargoes of Baltic timber, grain, and other produce from Europe, are constantly arriving in the Irish and the British Channel, to be ordered thence to whatever port they may be required, and be most marketable at, rendering a portion of the voyage to all intents and purposes a coasting voyage. And it is much to be feared that, not only as respects this class of shipping, but our ocean-going vessels as well, the British shipowner has not seen the worst, and that he will have to regret the expenditure which he is now making in the attempt, by increasing the sailing qualities of his ships, to compete with his active and more favourably situated rivals. The screw will shortly supersede the "clipper" in carrying merchandise, as the paddle-wheel has superseded every other mode of propulsion in carrying passengers and correspondence. And, in the meanwhile, the latter neutralises the advantages of early arrivals of merchandise, by preparing the consumer to expect it, and to make his arrangements accordingly. A cargo of tea, advised of by steamer and overland mail, although at a distance of two or three months' voyage, exercises nearly the same influence upon the market price as if it was already being landed in one of our ports. The building of expensive vessels calculated for speed in carrying would be an undoubted good under ordinary circumstances; but it is not a paying speculation. Moreover, other countries are rivalling us in this effort to improve our position; and in the mean time we are adding to a mercantile marine, which is unprofitable enough at its present extent.