полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 67, No. 416, June 1850

The Right Hon. the Earl of EGLINTON then came forward, amidst loud cheers, to move the following resolutions: – "That the cordial thanks of this meeting be respectfully offered to his Grace the Duke of Richmond, K.G., for his manly and consistent maintenance of the cause of Protection on all occasions, and especially for the able and impartial manner in which he has presided over the proceedings of this day." The noble earl said, that meeting had been characterised by more unanimity than any meeting, perhaps, at which he had ever assisted; but he felt certain that whatever might be the unanimity, and whatever might be the enthusiasm with which they had received the preceding resolutions, the one which he had then to propose would be received with still more unanimity, and with still greater enthusiasm. He had to propose the thanks of the meeting to their noble chairman. (Loud and long continued cheers.) Many censures had that day been unsparingly, but he should confess most justly, showered down upon that class to which he belonged. He was, however, proud to say, that he, in common with hundreds of others, had escaped from that censure. He was also proud to say that the class to which he more especially belonged – he meant the peerage of Scotland – had been particularly exempt from that vacillation and apathy which had distinguished too many of the nobility of the empire. (Hear, hear.) When he told them that out of 16 representative peers who sat in the House of Lords for Scotland, on the great division which took place with respect to the repeal of the corn laws, 10 had voted against the measure, 2 had not voted at all, one of whom was now as stanch a Protectionist as any present, and only 4 had recorded their votes against the principle of Protection – one of these being thousands of miles off, and perhaps incapable of forming any decision of his own upon the subject – when he told them those facts, he thought they would admit that the peerage of Scotland had not as a body been deficient in their duty upon that occasion. One of the most eloquent speakers who had addressed them that day, Professor Aytoun, had told them of some bad articles which came from Scotland in the shape of political economists. But he (the Earl of Eglinton) could not refrain from saying one word in favour of "Auld Scotland" upon that occasion, and he would ask them whether they had not seen one good article come from that country in the shape of the Professor himself? (Cheers.) It might not be so well known to the body of the meeting as it was to him, how deeply the Protectionist cause was indebted to that gentleman (hear); but he knew that the most powerful, the most eloquent, and the most convincing statements in favour of Protection had come from his pen. (Cheers.) He should also call to their recollection the honest specimen of a Scotch tenant-farmer – namely, Mr Watson, whom they had heard that day, and of whom he confessed he, as a countryman, felt proud, (hear, hear;) but, above all, he begged to state, that Scotland owned one-half of their noble chairman. The noble duke was one-half a Scotchman by birth, by property, and by feeling. (Hear, hear.) He knew that that was not a time of the day to go on descanting on all that they owed to the noble duke, and still more did he know that the presence of the noble duke did not afford the fitting opportunity for adopting such a course. He should say, however, that he well knew that there was not in that room, or in the country, a sincere well-wisher to the British empire, who did not look upon the noble duke as one of the most straightforward, one of the most gallant, and one of the most useful men whom this country ever possessed. (Cheers.) He should not detain them longer; but would content himself with leaving the resolution in their hands. (Great cheering.)

Lord JOHN MANNERS, M.P., came forward, amidst very loud and general cheering, to second the resolution. The noble lord said that in terminating the proceedings of that most remarkable meeting – remarkable not only for the ability of the speeches which they had heard, and the unanimity that had characterised their proceedings, but also for the presence of so many delegates, representing, and representing so truly, every suffering interest in this great community – he felt that he had a task at once most difficult and most gratifying to perform. Most truly had Lord Eglinton said that in the presence of the noble duke a certain reserve was necessary in speaking of those qualities which commanded their admiration; but still they should not be doing justice to their feelings if they permitted that opportunity to pass without saying that they did not know in the whole peerage one man who more justly commanded the respect, the admiration, and the affection of the industrious classes of this country. (Cheers.) Lord Eglinton had said some thing in favour of that house to which the noble duke belonged; and he (Lord J. Manners) hoped he might be allowed for one moment to say something in favour of that house to which he had so recently been returned. He could not, like some of the gentlemen who had that day addressed them, despair even of the present graceless House of Commons. (Hear, hear, and laughter.) If they asked him his reason, he should tell them that he found one in the fact, that, when that House of Commons had first met, the majority then against those principles which that meeting had assembled to enforce, and which they intended to carry into successful operation, amounted to not less than 100; while at the present moment that majority could not, he believed, be estimated at more than a score of votes. Another reason why he did not despair of the present House of Commons was derived from the recent election of the hon. and gallant colonel the member for Cork, who was then assisting at their proceedings. (Hear, hear.) He had no doubt but that at future elections they would continue further to increase the number of members ready to advocate and support their cause. If he might be permitted to give one word of advice, he would suggest that, while they took every precaution for returning, for the future, members who were prepared to vindicate the great principle of protection to native industry, they ought not to discourage, but to aid, those members in the present House of Commons who zealously sought to put down that system which they believed in their consciences to be working the destruction of this mighty empire. (Hear.) He should further say, that he found a fresh justification for a return of their somewhat waning confidence in the House of Lords, in the presence among them that day of the noble duke to whom they were going to offer by acclamation the vote of their unbounded confidence and admiration. (Cheers.) When they saw the noble duke supporting the dignity of the peerage with so much gallantry, so much honesty, and such unswerving onwardness of purpose, they might, he thought, well take courage; and believe that both Houses of Parliament would yet faithfully represent, and faithfully carry out, the principles on which the Constitution of this country had so long depended, and on which it must continue to depend if it was still to remain the Constitution of the greatest empire of the known world. (Hear, hear.) He called on them to vote by acclamation the resolution which he had the honour to second. He called upon them to rise as one man and give three lusty cheers for their noble chairman the Duke of Richmond. (The call was responded to with enthusiasm, the whole meeting rising as one man.)

The NOBLE DUKE proceeded to acknowledge the compliment as follows: – I rise, as you may well conceive that I must, impressed with a deep feeling of gratitude to you, the delegates from nearly every county in England and Scotland, for the very kind and flattering manner in which you have been pleased to pass the present resolution. I claim no merit for myself for what I have done in Parliament and out of Parliament, with the view of preventing the adoption of the Free-trade policy, or with a view of regaining protection to native industry. I claim no merit to myself for the course I have pursued, because I think that course is absolutely necessary, not only for the welfare and the prosperity of the landed interest of the country, but for the welfare of all classes of our fellow-subjects. (Hear, hear.) I never advocated protection to the farmer without also advocating protection to the silk weaver and to the manufacturer. (Hear, hear.) I am called on in Parliament not to legislate for one class, but to legislate for all classes, and I therefore have not pledged myself to the maintenance of the principle of protection without an earnest inquiry into the whole subject. I have, however, thought it my duty to give a pledge, and, with God's help, I will never violate it. (Cheers.) I am not made of that stuff which would permit me to veer about like the wind, and to flatter every popular demagogue. (Hear, hear.) I have one English quality in me, which is, that I will not be bullied into any course of which my judgment disapproves. (Hear, hear.) I will not allow a knot of Manchester Free-traders to dictate to the good sense of the community at large. (Hear, hear.) I will not consent to lose the colonies of this great empire. (Hear, hear.) I will not help to carry out a system which is bringing ruin to our shipping interest, (cheers,) and which forces to emigration those honest and industrious mechanics, who, by their skill, their energy, and their good conduct, have, up to the time of the repeal of the Navigation Laws, been able to get a fair day's wages for a fair day's work. (Cheers.) Neither will I consent to have the honour and glory of this great country dependent upon Mr Cobden and his party. (Cheers.) I am for English ships, manned by English hearts of oak. (Renewed cheers.) I am for protecting domestic industry in all its branches. (Hear, hear.) I feel, however, that at this time of the evening I ought not to trespass at any length on your attention; but cordially agreeing with all the resolutions that have been put here to-day, and carried unanimously, and agreeing with much that has fallen from the different eloquent gentlemen who have addressed you, I must speak out my own mind; and I hope that you, the farmers of England, will not respect me the less for doing so. (Hear.) Well, then, I must say that I only recommend constitutional means, (hear, hear,) and I certainly do not recommend the adoption of any threats of violence or force, and still less do I recommend that we should band ourselves together not to pay taxes, (Hear, hear.) We are the representatives of a truly loyal people. By constitutional means we shall gain a victory of which we shall afterwards have reason to be proud; but if we descend to the miserable and degrading tricks of the Anti-Corn Law League, (hear, hear,) we cannot be respected, because we cannot respect ourselves. I thank you for the confidence you have shown towards me. I thank you, in my own name, and in the name of many Protectionists who have not been able to be present here to-day, for the unanimous manner in which you have carried the resolutions, and the patience with which you have listened to him who is now addressing you, who is so little worthy of attention. But as long as I shall continue to have health, I shall take every opportunity of meeting the tenant-farmers of this country, (hear, hear,) notwithstanding that I may be told in the House of Lords, in a majority of whose members I have no confidence, (hear, hear,) that by presiding at meetings of this description I am creating a panic among the tenantry. That, gentlemen, is the last attack that has been made on me and on my noble friends around me. I was told the other night, in the House of Lords, by a noble lord who is a disciple of Sir R. Peel, that it was to myself and to those who pursued a similar course to mine that the lowness in the price of corn is to be attributed. (Hear, hear, and laughter.) His assertion was, "That the speeches delivered in this country found their way into the German newspapers, and that the German farmers, believing that shortly a duty on the import of foreign corn would be imposed, sent over their corn to this country and sold it here at a loss." In reply I stated that, if this statement was correct, I could not regret that I had contributed to the foreigners losing money, if they choose to send their corn here. I have no bad feeling to the foreigner; but I may say that, if we are exposed to taxes from which he is exempt, I could feel no pity for any loss that he might sustain in his competition with the agriculturists of this country. (Cheers.) One word on the subject of the income tax, which is now so oppressive to the tenant-farmer. When I stated in the House of Lords, a few evenings ago, that the farmers had no right to be called upon to pay that tax whilst they derived no profit from their holdings, Lord Grey said that he admitted the hardness of the case, but that he and his party had not originally enacted the law, but that it emanated from Sir R. Peel. (Hear, hear, and laughter.) To that I felt it my duty to say, that although they did not originally enact the law, they had extended the time of its operation. (Hear, hear.) At the same time, I certainly did not attempt to justify Sir R. Peel; for I would be the last man to undertake such a task. (Hear, hear.) I again thank you for the confidence you have shown towards me; and if my services can ever be of the slightest use to the tenantry of this country, or to its domestic industry, I can only say that those services, such as they are, will ever be at your disposal. (The noble Duke concluded amidst enthusiastic cheering.)

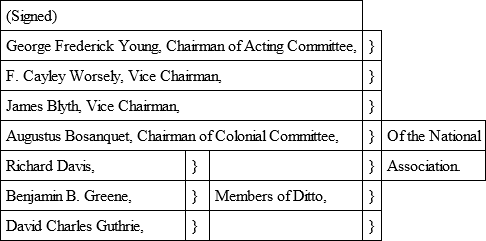

The meeting immediately separated, Mr G. F. Young informing the delegates that the National Association was anxious for their presence at their rooms, at the South Sea House, on the following morning, at eleven o'clock.

PRESENTATION OF THE MEMORIAL TO LORD JOHN RUSSELLThe delegates re-assembled in considerable numbers at the South Sea House on Saturday morning, when they agreed to the following address to the Prime Minister, which had been prepared, in conformity with the resolutions passed at the great aggregate meeting at the Crown and Anchor on Tuesday last: —

"TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD JOHN RUSSELL, M.P., FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY, &c"May it please your Lordship, – We are deputed to address you in the name and at the desire of a public meeting held in this metropolis on the 7th inst., which, consisting of a considerable number of members of both Houses of Parliament, merchants, shipowners, tradesmen, and others connected with the most important interests of the nation, and comprising nearly 500 owners and occupiers of land, specially delegated by the agriculturists of every part of the United Kingdom, to represent the present condition of their respective localities, and to express their opinion on the public policy of your lordship's administration, presents a just claim to the serious attention of her Majesty's Government.

"On the authority of this meeting, unanimously expressed, it is our duty to declare to your lordship that intolerable distress now almost universally pervades the British agricultural interest; that many branches of the colonial interest are fast sinking into ruin; that the shipping and other great interests of the country are involved in difficulty and deep depression; and that large masses of the industrial population are reduced to a state of lamentable deprivation and suffering.

"It must be obvious that such a condition of affairs is fraught with consequences disastrous to the public welfare; and if not speedily remedied, it is the conviction of the meeting that it will endanger the public peace, prove fatal to the maintenance of public credit, and may even place in peril the safety of the State.

"It is our duty further to declare to your lordship that the dangerous evils we have thus described are, in the deliberate judgment of the meeting, attributable to the recent changes made in those protective laws by which the importation of articles of foreign production had long been regulated, which changes it regards as most rash and impolitic. It considers the ancient system of commercial law to have been based on the most just principles, and dictated by the soundest views of national policy. It cannot forget that, under that system, Great Britain attained an unexampled state of prosperity and a proud pre-eminence in the scale of nations; and it is its firm conviction that if the principle of fostering and protecting British industry and British capital be abandoned, many of the most important interests of the State will be utterly and cruelly sacrificed, and the national prosperity and greatness be ruinously impaired.

"The meeting is further of opinion that no relief from general or local taxation, which would be consistent with the maintenance of public faith and the efficiency of public establishments, could enable the British and colonial producer successfully to compete with foreign productions; and that the only hope of replacing the agricultural and other native and colonial interests in a state of prosperity rests on the re-establishment of a just system of import duties.

"The meeting deeply deplores that the distressing and destructive consequences of the system of miscalled Free Trade having been repeatedly and urgently pressed on the attention of Parliament, the House of Commons has treated the just complaints of the people with indifference, has exhibited a total want of sympathy for their sufferings, and has refused to adopt any measures for removing or alleviating the prevalent difficulty and distress.

"This conduct has naturally produced a widely-diffused feeling of disappointment, discontent, and distrust, which is rapidly undermining the reliance of the people in the justice and wisdom of Parliament, the best security for loyalty to the Throne, and for the maintenance of the invaluable institutions of the country.

"Having thus faithfully represented to your lordship the general views on the policy of the country, expressed in the recorded resolutions of the meeting we represent, we proceed to discharge the further duty intrusted to us of addressing your lordship as the head of that Administration by which the policy so strongly deprecated is continued and defended.

"We are charged earnestly to remonstrate and protest on the part of the deeply injured thousands whose property has been torn from them by the unjust and suicidal impolicy of which we complain; and still more emphatically on behalf of the millions of the industrial population dependent on them for employment, and consequently for subsistence, against the longer continuance of a system which, under the specious name of Free Trade, violates every principle of real freedom, since it dooms the taxed, fettered, and disqualified native producer to unrestricted competition in his own market with the comparatively unburdened foreigner. We not only deny the moral right of any government or of any legislature to have involved in certain loss and suffering large masses of a flourishing community, for the sake of giving trial to a mere experiment; but we assert that the experiment has been tried, and has signally and disastrously failed, and we demand therefore, as the right of those we represent, the prompt restoration of that protection from unrestricted foreign import which can alone rescue them from impending destruction.

"It is painful for us to declare, but it is our duty not to disguise, that the pertinacious adherence of the Cabinet, of which your lordship is at the head, to the policy of miscalled Free Trade, and its determined rejection of the appeals of the people for a reversal of that policy, have extended to the executive government of the country the same feelings of distrust and discontent which are widely diffused with respect to the representative branch of the Legislature. We solemnly adjure your lordship to remember that discontent unattended to may ripen into disaffection.

"We know that the loyalty of the people to their most gracious Sovereign, under all their grievances and wrongs, remains, and will remain, unshaken; but we are aware, and it is our duty, therefore, to warn her Majesty's Government, that the state of feeling in many districts of the country is most critical and alarming, hazardous to its peace, perilous to the maintenance of public credit, and dangerous to its established institutions; nor must we be deterred, either by our unqualified respect for your lordship's personal character, or by the just consideration we owe to the elevated position you occupy, from casting on your lordship and your colleagues the awful responsibility of all the consequences that may result from a continuance of your refusal either to redress the wrongs of the people, or to allow them the constitutional opportunity for the vindication of their rights, by dissolving the Parliament and appealing to the voice of the country.

"London, May 11, 1850."

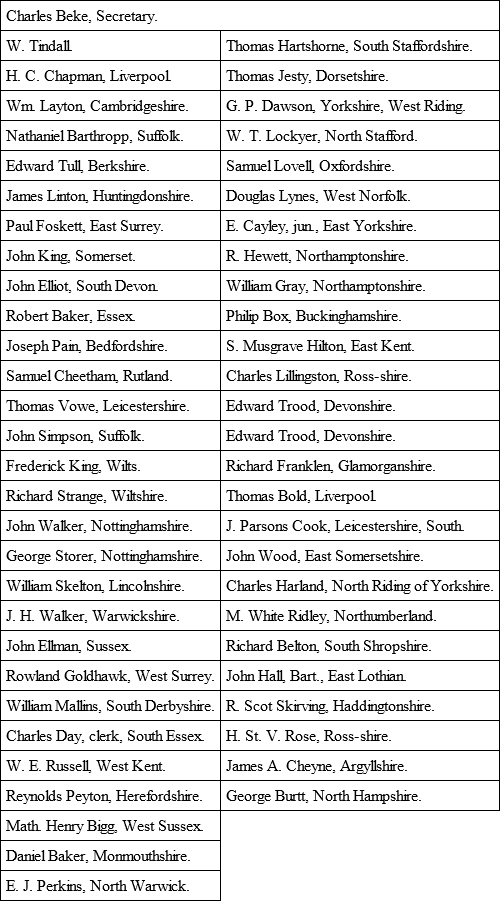

Shortly after twelve o'clock the deputation proceeded to the Premier's official residence in Downing Street. It consisted of the several gentlemen whose names were appended to the address, and was accompanied by Mr Newdegate, M.P., Colonel Sibthorp, M.P., Mr Bickerton, (Shropshire,) Sir J. F. Walker Drummond, Bart., (Midlothian,) Mr Hugh Watson, (Keillor,) Forfarshire; Mr John Dudgeon, (Spylaw,) Roxburghshire, &c.

On the deputation being ushered into the reception-room, Lord John Russell welcomed the gentlemen composing it with characteristic courtesy, and cordially shook Mr Young by the hand, at the same time expressing his regret that the Duke of Richmond was unable to attend.

Mr Young. – I was about to explain to your lordship that his Grace is unable to attend from indisposition, and that I this morning received a letter from his Grace, which I will read to your lordship: —

"Goodwood, May 10, 1850.""My Dear Sir, – I write to ask you to make my excuses to the deputation if I do not make my appearance to-morrow at a quarter past twelve in Downing Street. I have not been able to leave my room to-day from a violent cold and rheumatism, and if not better, shall not be able to go to London for some days.

"Believe me, my dear sir, yours sincerely,"G. F. Young, Esq. (Signed) "Richmond."Mr Young continued – I feel deep regret that his Grace is unable to attend here to-day; but I beg to assure your lordship that we have his Grace's concurrence in all our proceedings, and I am about to place in your lordship's hands a document which has been drawn up under his full sanction, and to which his Grace's signature would have been affixed if his absence from indisposition had not prevented it, and we had not been ignorant of that fact until it was too late to transmit it to him for signature. Your Lordship is, no doubt, aware that a large public meeting took place in this metropolis on Tuesday last, at which certain resolutions were adopted relative to protection to native industry; and amongst them one appointing a deputation to wait upon your lordship with a memorial, and to furnish you with such explanations as you may require. With your lordship's permission, I will now proceed to read the address with which I have the honour to be intrusted. Mr Young here read the address, and continued thus: – I do not know, my lord, that it becomes me to make any comments upon this document, which has been prepared with the unanimous assent of the gentlemen whom I have here with me to-day, except to refer you generally to the opinions which it contains, and on their behalf to tender any explanation which your lordship may deem requisite in reference to the assertions therein made, or to any point connected with the subject which is now brought under your lordship's notice with very great pain on the part of those for whom I have the honour to speak.

Lord J. Russell. – I may be allowed to say – and I do not do so without due consideration – that, of course, I am ready at all times to take upon myself all the responsibility which belongs to the executive government; but with regard to the assertions in this address respecting the House of Commons, you state – "That the meeting is further of opinion that no relief from general or local taxation which would be consistent with the maintenance of public faith, and the efficiency of public establishments, could enable the British and colonial producer successfully to compete with foreign productions." Now, that proposal for relief from general and local taxation, consistent with the maintenance of public faith and the efficiency of public establishments, is, in fact, the only proposition of a large nature that has been rejected by the House of Commons. You also say here, "that the only hope of replacing the agricultural and other native and colonial interests in a state of prosperity, rests on the re-establishment of a just system of import duties." I do not deny, or wish in any way to shrink from the responsibility which rests upon her Majesty's government for the line of policy they have adopted; but no such proposition has been made to the House of Commons, and the House of Commons has not rejected any such proposition.