полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 66, No 409, November 1849

In addition to these admirable observations, it may be stated, as another, and perhaps the principal reason why transportation, when conducted on proper principles, is attended with such immediate and beneficial influences on the moral character of the convict, that it places him in situations where scope is afforded for the development of the domestic and generous affections. A counterpoise is provided to self. It is the impossibility of providing such a counterpoise within the four walls of a cell – the extreme difficulty of finding it, in any circumstances in which a prisoner can be placed, on his liberation from jail in his own country, which is the chief cause of the total failure of all attempts to work a moral reform on prisoners, when kept at home, by any, even the most approved system of jail discipline. But that which cannot be obtained at home is immediately, on transportation, found in the colonies. The criminal is no longer thrown back on himself in the solitude of a cell – he is not surrounded by thieves and prostitutes, urging him to resume his old habits, on leaving it. The female convict, on arriving in New South Wales, is almost immediately married; ere long the male, if he is industrious and well-behaved, has the means of being so. Regular habits then come to supplant dissolute – the natural affections spring up in the heart with the creation of the objects on which they are to be exercised. The solitary tenant of a cell – the dissolute frequenter of spirit-cellars and bagnios, acquires a home. The affections of the fireside begin to spring up, because a fireside is obtained.

Incalculable is the effect of this change of circumstances on the character of the most depraved. Accordingly it is mentioned by Mr Cunningham, in his very interesting Account of New South Wales, that great numbers of young women taken from the streets of London, who have resisted all efforts of Christian zeal and philanthropy in Magdalene Asylums or Penitentiaries at home, and embark for New South Wales in the most shocking state of depravity, become sensibly improved in their manners, and are not unfrequently entirely reformed by forming, during the voyage, temporary connections with sailors, to whom, when the choice is once made, they generally remain faithful: so powerful and immediate is the effect of an approach even to a home, and lasting ties, on the female heart.6 The feelings which offspring produces are never entirely obliterated in the breast of woman. It has been often observed, that though dissolute females generally, when they remain at home, find it impossible to reform their own lives, yet they rarely, if they have the power, fail to bring up their children at a distance from their haunts of iniquity. So powerful is the love of children, and the secret sense of shame at their own vices, in the breasts even of the most depraved of the female sex.

It has been proved, accordingly, by experience, on the very largest scale, not only that the reformation of offenders, when transported to a colony in a distant part of the world, takes place, if they are preserved in a due proportion of numerical inferiority to the untainted population, to an extent unparalleled in any other situation; but that, when so regulated, they constitute the greatest possible addition to the strength, progress, and riches of a colony. From official papers laid before parliament, before the unhappy crowding of convicts in New South Wales began, and the gang-system was introduced, it appears that between the years 1800 and 1817 – that is, in seventeen years – out of 17,000 convicts transported to New South Wales, no less than six thousand had, at the close of the period, obtained their freedom from their good conduct, and had earned among them, by their free labour, property to the amount of £1,500,000! It may be safely affirmed that the history of the world does not afford so astonishing and gratifying an instance of the moral reformation of offenders, or one pointing so clearly to the true system to be pursued regarding them. It will be recollected that this reformation took place when 17,000 convicts were transported in seventeen years – that is, on an average, 1000 a-year only – and when the gang-system was unknown, and the convict on landing at Sidney was immediately assigned to a free colonist, by whom he was forthwith marched up the country into a remote situation, and employed under his master's direction in rural labour or occupations.

And that the colony itself prospers immensely from the forced labour of convicts being added, in not too great proportions, to the voluntary labour of freemen, is decisively proved by the astonishing progress which Australia has made during the last fifty years; the degree in which it has distanced all its competitors in which convict labour was unknown; and the marvellous amount of wealth and comfort, so much exceeding upon the whole that known in any other colony, which now exists among its inhabitants. We say upon the whole, because we are well aware that in some parts of Australia, particularly Van Diemen's Land, property has of late years been most seriously depreciated in value – partly from the monetary crisis, which has affected that distant settlement as well as the rest of the empire, and partly from the inordinate number of convicts who have been sent to that one locality, from the vast increase of crime at home, and the cessations of transportation to Sidney; – a number which has greatly exceeded the proper and salutary proportion to freemen, and has been attended with the most disastrous results. But that the introduction of convicts, when not too depraved, and kept in due subordination by being in a small minority compared to the freemen, is, so far from being an evil, the greatest possible advantage to a colony, is decisively proved by the parliamentary returns quoted below, showing the comparative progress during a long course of years of Australia, aided by convict labour, and the Cape of Good Hope and Canada, which have not enjoyed that advantage. These returns are decisive. They demonstrate that the progress of the convict colonies, during the last half century, has been three times as rapid as that of those enjoying equal or greater advantages, to whom convicts have not been sent; and that the present state of comforts they enjoy, as measured by the amount per head of British manufactures they consume, is also triple that of any other colony who have been kept entirely clear from the supposed stain, but real advantages, of forced labour.7

Accordingly, the ablest and best-informed statistical writers and travellers on the Continent, struck with the safe and expeditious method of getting quit of and reforming its convicts which Great Britain enjoys, from its numerous colonies in every part of the world, and the want of which is so severely felt in the Continental states, are unanimous in considering the possession of such colonies, and consequent power of unlimited transportation, as one of the very greatest social advantages which England enjoys. Hear what one of the most enlightened of those writers, M. Malte-Brun, says on the subject: —

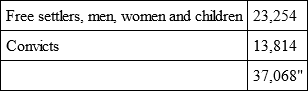

"England has long been in the habit of disposing of its wicked citizens in a way at once philosophic and politic, by sending them out to cultivate distant colonies. It was thus that the shores of the Delaware and the Potomac were peopled in America. After the American war, they were at a loss where to send the convicts, and the Cape of Good Hope was first thought of; but, on the recommendation of the learned Sir Joseph Banks, New South Wales obtained the preference. The first vessel arrived at Botany Bay on the 20th January 1788, and brought out 760 convicts, and according to a census taken in 1821, exhibited the following results in thirty-three years, viz. —

In 1832, that population had risen to 40,000 souls.8 In 1821, there were in the colony 5000 horses, 120,000 horned cattle, and 350,000 sheep. It consumed, at that period, 8,500,000 francs' (£340,000) worth of English manufactures, being about £8, 10s. a-head, and exported to Europe about £100,000 worth in rude produce.

"Great division of opinion has existed in France, for a long course of years, on the possibility of diminishing the frequency of the punishment of death, as well as that of the galleys; but a serious difficulty has been alleged in the expense with which an establishment such as New South Wales would cost. It is worthy of remark, however, that from 1789 to the end of 1821, England had expended for the transport, maintenance, and other charges of 33,155 convicts, transported to New South Wales, £5,301,023, being scarce a third of what the prisoners would have cost in the prisons of Great Britain, without having the satisfaction of having changed into useful citizens those who were the shame and terror of society.

"When a vessel with convicts on board arrives in the colony, the men who are not married in it, are permitted to choose a wife among the female convicts. At the expiration of his term of punishment, every convict is at liberty to return to his own country, at his own expense. If he chooses to remain, he obtains a grant of land, and provisions for 18 months: if he is married the allotment is larger, and an adequate portion is allowed for each child. Numbers are provided with the means of emigration at the expense of government; they obtain 150 acres of land, seed-corn, and implements of husbandry. It is worthy of remark that, thanks to the vigilance of the authorities, the transported in that colony lose their depraved habits; that the women become well behaved and fruitful; and that the children do not inherit the vices of their parents. These results are sufficient to place the colony of New South Wales among the most noble philanthropic institutions in the world. After that, can any one ask the expense of the establishment?" – Malte-Brun, Géographie Universelle, xii. 194-196.

But here a fresh difficulty arises. Granting, it will be said, that transportation is so immense a benefit to the mother country, in affording a safe and certain vent for its criminals; and to the colonies, by providing them with so ample a supply of forced labour, what is to be done when they will not receive it? The colonies are all up in arms against transportation; not one can be persuaded, on any terms, to receive these convicts. When a ship with convicts arrives, they begin talking about separation and independence, and reminding us of Bunker's Hill and Saratoga. The Cape shows us with what feelings colonies which have not yet received them view the introduction of criminals; Van Diemen's Land, how well founded their apprehensions are of the consequences of such an invasion of civilised depravity. This difficulty, at first sight, appears not only serious but insurmountable. On a nearer examination, however, it will be found that, however formidable it may appear, it could easily be got over; and that it is entirely owing to the true principles of transportation having been forgotten, and one of the first duties of government neglected by our rulers for the last thirty years.

It is very remarkable, and throws an important light on this question, that this horror at the influx of convicts, which has now become so general in the colonies as to render it almost impossible to find a place where they can with safety be landed, is entirely of recent origin. It never was heard of till within the last fifteen or twenty years. Previous to that time, and even much later, transportation was not only regarded by the penal colonies without aversion, but with the utmost possible complacency. They looked to a series of heavy assizes in Great Britain with the same feelings of anxious solicitude, as the working classes do to a good harvest, or the London tradesman to a gay and money-spending season. Spirits never were so high in Sidney, speculation never so rife, property never so valuable, profits never so certain, as when the convict ships arrived well stored with compulsory emigrants. If any one doubts this, let him open the early numbers of the Colonial Magazine, and he will find them filled with resolutions of public meetings in New South Wales, recounting the immense advantages the colony had derived from the forced labour of convicts, and most earnestly deprecating any intermission in their introduction. As a specimen, we subjoin a series of resolutions, by the Governor and Council of New South Wales, on a petition agreed to, at a public meeting held in Sidney, on 18th February 1838.

Resolutions of the Legislative Council, New South Wales, 17th July 18384. Resolved.– That, in opinion of this council, the numerous free emigrants of character and capital, including many officers of the army and navy, and East India Company's service, who have settled in this colony, with their families, together with a rising generation of native-born subjects, constitute a body of colonists who, in the exercise of the social and moral relations of life, are not inferior to the inhabitants of any other dependency of the British crown, and are sufficient to impress a character of respectability upon the colony at large.

5. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, the rapid and increasing advance of this colony, in the short space of fifty years from its first establishment, in rural, commercial, and financial prosperity, proves indisputably the activity, the enterprise, and industry of the colonists, and is wholly incompatible with the state of society represented to exist here.

6. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, the strong desire manifested by the colonists generally, to obtain moral and religious instruction, and the liberal contributions, which have been made from private funds, towards this most essential object, abundantly testify that the advancement of virtue and religion amongst them is regarded with becoming solicitude.

7. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, if transportation and assignment have hitherto failed to produce all the good effects anticipated by their projectors, such failure may be traced to circumstances, many of which are no longer in existence, whilst others are in rapid progress of amendment. Amongst the most prominent causes of failure may be adduced the absence, at the first establishment of the colony, of adequate religious and moral instruction, and the want of proper means of classification in the several gaols throughout the colony, as well as of a sufficient number of free emigrants, properly qualified to become the assignees of convicts, and to be intrusted with their management and control.

8. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, the great extension which has latterly been afforded of moral and religious instruction, the classification which may in future be made in the numerous gaols now in progress of erection, upon the most approved principles of inspection and separation, the most effectual punishment and classification of offenders in ironed gangs, according to their improved system of management – the numerous free emigrants now eligible as the assignees of convicts, and the accumulated experience of half a century – form a combination of circumstances, which renders the colony better adapted at the present, than at any former period, to carry into effect the praiseworthy intentions of the first founders of the system of transportation and assignment, which had no less for its object reformation of character than a just infliction of punishment.

9. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, no system of penal discipline, or secondary punishment, will be found at once so cheap, so effective, and so reformatory, as that of well-regulated assignment – the good conduct of the convict, and his continuance at labour, being so obviously the interest of the assignee; whilst the partial solitude and privations, incidental to a pastoral or agricultural life in the remote districts of the colony, (which may be made the universal employment of convicts,) by effectually breaking a connexion with companions and habits of vice, is better calculated than any other system to produce moral reformation, when accompanied by adequate religious instruction.

10. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, many men who, previously to their conviction, had been brought up in habits of idleness and vice, have acquired, by means of assignment, not only habits of industry and labour, but the knowledge of a remunerative employment, which, on becoming free, forms a strong inducement to continue in an honest course of life.

11. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, the sudden discontinuance of transportation and assignment, by depriving the colonists of convict labour, must necessarily curtail their means of purchasing crown lands, and, consequently, the supply of funds for the purpose of immigration.

12. Resolved.– That, in the opinion of this council, the produce of the labour of convicts, in assignment, is thus one of the principal, though indirect means, of bringing into the colony free persons: it is obvious, therefore, that the continuance of emigration in any extended form, must necessarily depend upon the continuance of the assignment of convicts.9

It is not surprising that they viewed, at this period, the transportation system in this light; for under it they had made advances in population, comfort, and riches, unparalleled in any other age or country of the world.

How, then, has it happened that so great a change has come over the views of the colonists on this subject; and that the system which they formerly regarded, with reason, as the sheet-anchor of their prosperity, is now almost universally looked to with unqualified aversion, as the certain forerunner of their destruction? The answer is easy. It is because transportation, as formerly conducted, was a blessing, and because, as conducted of late years, it has become a curse, that the change of opinion has arisen in regard to it. The feelings of the colonists, in both cases, were founded on experience – both were, in the circumstances in which they arose, equally well founded, and both were therefore equally entitled to respect and attention. We have only to restore the circumstances in which the convicts were a blessing, to revive the times in which their arrival will be regarded as a boon. And to effect this, can easily be shown not only to be attended with no difficulty, but only to require the simultaneous adoption by government of a system of punishment at home, and of voluntary emigration at the public expense abroad, attended with a very trifling expense, and calculated to relieve, beyond any other measure that could by possibility be devised, the existing distress among the labouring classes of Great Britain and Ireland.

To render the introduction of penal labour into a colony an advantage, three things are necessary. 1st, that the convicts sent out should be for the most part instructed in some simple rural art or occupation, of use in the country into which they are to be transplanted. 2d, that they should in general be beginners in crime, and a small number of them only hardened in depravity. 3d, what is most important of all, that they should be preserved in a due proportion, never exceeding a fourth or a fifth to the free and untainted settlers. Under these conditions, their introduction will always prove a blessing, and will be hailed as a boon. If they are neglected, they will prove a curse, and their arrival be regarded as a punishment.

Various circumstances have contributed, of late years, to render the convict system a dreadful evil, instead of, as formerly, a signal benefit to the colonies. But that affords no ground for despair; on the contrary, it furnishes the most well-grounded reason for hope. We are suffering under the effects of an erroneous regimen, not any inherent malady in the patient. Change this treatment, and his health will soon return.

It is well known that the greatest pains have of late years been taken, in this country, to instruct prisoners in jail in some useful handicraft; and that, so far has this been carried, that our best-regulated jails are more in fact great houses of industry. The general penitentiary at Pentonville, in particular, where the convicts sentenced to transportation are trained, previous to their removal to the penal settlements, is a perfect model of arrangement and attention in this important respect. But it is equally well known that it is only of late years that this signal reform has come into operation; and we have the satisfaction of knowing that already its salutary effects have been evinced, in the most signal manner, with the convicts sent abroad. Previous to the year 1840, scarcely anything was done on any considerable scale, either to teach ordinary prisoners trades in jail, to separate them from each other, or to prepare them, in the public penitentiaries, for the duties in which they were to be engaged, when they arrived at their distant destination. The county jails, now resounding with the clang of ceaseless occupation, pursued by prisoners in their separate cells, then only re-echoed the din of riot and revelling in the day-rooms where the idle prisoners were huddled together, and beguiled the weary hours of their captivity by stories of perpetrated crime, or plans for its renewal the moment they got out of confinement. But the ideas of men are all formed on the experience of facts, or the thoughts driven into them, for a considerable time back. The present universal horror at transportation is founded on the experience of the prisoners with which, for a quarter of a century, New South Wales had been flooded, from the idle day-rooms or profligate hulks of Great Britain. Some years must elapse before the effects of the improved discipline received, and laborious habits acquired, in the jails and penitentiaries of the mother country, produces any general effect on public opinion in its distant colonies.

The relaxation of the severity of our penal code at home, during the last thirty years, however loudly called for by considerations of justice and humanity, has undoubtedly had a most pernicious influence on the class of convicts who have, during that period, been sent to the colonies. In so far as that change of system has diminished the frequency of the infliction of the punishment of death, and limited, practically speaking, that dreadful penalty to cases of wilful and inexcusable murder, it must command the assent of every benevolent and well-regulated mind. But, unfortunately, the change has not stopped there. It has descended through every department of our criminal jurisprudence, and come in that way to alter much for the worse the class of criminals who of late years have been sent to the penal colonies. The men who were formerly hanged are now for the most part transported; those formerly transported are now imprisoned; and those sent abroad have almost all, on repeated occasions, been previously confined, generally for a very long period. As imprisonment scarcely ever works any reformation on the moral character or habits of a prisoner, whatever improved skill in handicraft it may put into his fingers, this change has been attended with most serious and pernicious effect on the character of the convicts sent to the colonies, and gone far to produce the aversion with which they are now everywhere regarded.

It has been often observed, by those practically acquainted with the working of the transportation system in the colonies, that the Irish convicts were generally the best, and the Scotch, beyond all question, the worst who arrived. This peculiarity, so widely different from, in fact precisely the reverse of, what has been observed of the free settlers from these respective countries, in every part of the world, has frequently been made the subject of remark, and excited no little surprise. But the reason of it is evident, and, when once stated, perfectly satisfactory. The Scotch law, administered almost entirely by professional men, and on fixed principles, has long been based on the principle of transporting persons only who were deemed irreclaimable in this country. Very few have been sent abroad for half a century, from Scotland, who had not either committed some very grave offence, or been four or five times, often eight or ten times, previously convicted and imprisoned. In Ireland, under the moderate and lenient sway of Irish county justices, a poacher was often transported who had merely been caught with a hare tucked up under his coat. Whatever we may think of the justice of such severe punishments for trivial offences, in the first instance, there can be but one opinion as to its tendency to lead a much better class of convicts from the Emerald Isle, than the opposite system did from the shores of Caledonia. Very probably, also, the system of giving prisoners "repeated opportunities of amendment," as it is called in this country – but which, in fact, would be more aptly styled "renewed opportunities for depravity" – has, from good but mistaken motives, been carried much too far in Scotland. Be this as it may, nothing is more certain than that the substitution of a race of repeatedly convicted and hardened offenders, under the milder system of punishment in Great Britain, during the last twenty years, for one comparatively uninitiated in crime, such as were formerly sent out, has had a most pernicious effect on the character of the convicts received in the colonies, and the sentiments with which their arrival was regarded.