полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 66, No 405, July 1849

We say advisedly, each interest has looked on with indifference when its neighbour was destroyed. That this strong phrase is not misapplied to the effect of these measures in the West Indies, is too well known to require any illustration. Ruin, widespread and universal, has, we know by sad experience, overtaken, and is rapidly destroying these once splendid colonies. While we write these lines, a decisive proof17 has been judicially afforded of the frightful depreciation of property which has there taken place, from the acts of successive administrations acting on liberal principles, and yielding to popular outcries: the fall has amounted to ninety-three per cent. Beyond all doubt, since the new system began to be applied to the West Indies, property to the amount of a hundred and twenty millions has perished under its strokes. The French Convention never did anything more complete. Free-trade fanaticism may well glory in its triumphs; it is doubtful if they have any parallel in the annals of mankind.

We do not propose to resume the debate on the Navigation Laws, of which the public have heard so much in this session of parliament. We are aware that their doom is sealed; and we accept the extinction of shipping protection as un fait accompli, from which we must set out in all future discussions on the national prospects and fortunes. But, in order to show how enormously perilous is the change thus made, and what strength of argument and arrays of facts free-trade fanaticism has had the merit of triumphing over, we cannot resist the temptation of transcribing into our pages the admirable letter of Mr Young, the able and unflinching advocate of the shipping interest, to the Marquis of Lansdowne, after the late interesting debate on the subject in the House of Lords. We do so not merely from sincere respect for that gentleman's patriotic spirit and services, but because we do not know any document which, in so short a space, contains so interesting a statement of that leading fact on which the whole question hinges – viz. the progressive and rapid decline of British, and growth of foreign tonnage, with those countries with whom we have concluded reciprocity treaties: affording thus a foretaste of what we may expect now that we have established a reciprocity treaty, by the repeal of the Navigation Laws, with the whole world:

"My Lord, – In the debate last night on the Navigation Laws, your Lordship said, —

'The noble and learned Lord opposite has spoken contemptuously of statistics. Let me remind that noble and learned Lord that if any statement founded on statistics remains unshaken, it is the statement that under reciprocity treaties now existing, by which this country enjoys no protection, she, nevertheless, monopolises the greater part of the commerce of the north of Europe.'

As an impartial statist, as well as a statesman, your Lordship will perhaps permit me to invite your attention to the following abstract from Parliamentary returns, respectfully trusting that, if the facts it discloses should be found irreconcilable with the opinions you have expressed, a sense of justice will induce your Lordship to correct the error: —

The reciprocity treaty with the United States was concluded in 1815.

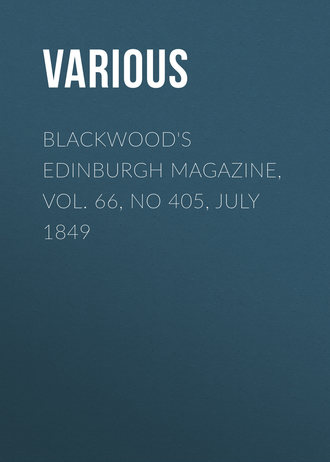

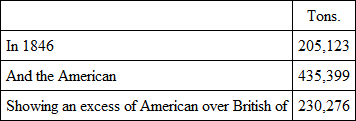

The British inward entries from that country were —

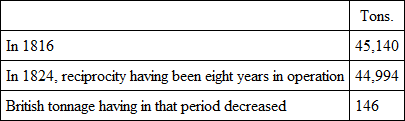

The inward entries of American tonnage were —

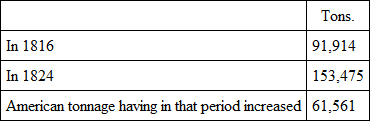

During that period no reciprocity existed with the Baltic Powers; and

Thus, from the peace in 1815 to 1824, when the "Reciprocity of Duties Act" passed, in the trade of the only country in the world with which great Britain was in reciprocity, her tonnage declined 146 tons, and that of the foreign nation advanced 61,561 tons; while in the trade with the Baltic powers, with which no reciprocity existed, British tonnage advanced on its competitors in the proportion of 51,362 to 31,443 tons.

From 1824 the reciprocity principle was applied to the Baltic powers; and —

And during this same period, the proportion of tonnage of the United States continued, under the operation of the same principle, steadily to advance, the British entries thence being —

I have (I hope not unfairly) introduced into this statement American tonnage, because it shows that while, in the period antecedent to general reciprocity, the adoption of the principle in the trade with that nation produced an actual decline of British navigation, while in the trade with the Baltic powers, which was free from that scourge, British navigation outstripped its competitor, it exhibits in a remarkable manner the reverse result, from the moment the principle was applied to the Baltic trade; while, above all, it completely negatives the statement of the greater part of the commerce of the north of Europe being monopolised by British ships, showing that in that commerce, in 1846, of an aggregate of 660,055 tons, British shipping had only 88,894 tons, while no less than 571,161 tons were monopolised by Baltic ships!"

It is evident, from this summary, that the decline of British and growth of foreign shipping will be so rapid, under the system of Free Trade in Shipping, that the time is not far distant when the foreign tonnage employed in conducting our trade will be superior in amount to the British. In all probability, in six or seven years that desirable consummation will be effected; and we shall enjoy the satisfaction of having purchased freights a farthing a pound cheaper, by the surrender of our national safety. It need hardly be said that, from the moment that the foreign tonnage employed in conducting our trade exceeds the British, our independence as a nation is gone; because we have reared up, in favour of states who may any day become our enemies, a nursery of seamen superior to that which we possess ourselves. And every year, which increases the one and diminishes the other, brings us nearer the period when our ability to contend on our own element with other powers is to be at end, and England is to undergo the fate of Athens after the catastrophe of Aigos Potamos – that of being blockaded in our own harbours by the fleets of our enemies, and obliged to surrender at discretion on any terms they might think fit to impose.

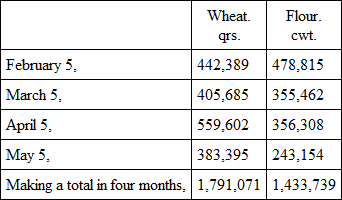

But in truth, the operations of the free-traders will, to all appearance, terminate our independence, and compel us to sink into the ignoble neutrality which characterised the policy of Venice for the last two centuries of its independent existence, before the foreign seamen we have hatched in our bosom have time to be arrayed in a Leipsic of the deep against us. So rapid, so fearfully rapid, has been the increase in the importation of foreign grain since the repeal of the corn laws took place, and so large a portion of our national sustenance has already come to be derived from foreign countries, that it is evident, on the first rupture with the countries furnishing them, we should at once be starved into submission. The free-traders always told us, that a considerable importation of foreign grain would only take place when prices rose high; that it was a resource against seasons of scarcity only; and that, when prices in England were low, it would cease or become trifling. Attend to the facts. Free trade in grain has been in operation just three years. We pass over the great importation of the year 1847, when, under the influence of the panic, and high prices arising from the Irish famine, no less than 12,000,000 quarters of grain were imported in fifteen months, at a cost of £31,000,000, nearly the whole of which was paid in specie. Beyond all doubt, it was the great drain thus made to act upon our metallic resources – at the very time when the free-traders had, with consummate wisdom, established a sliding paper circulation, under which the bank-notes were to be withdrawn from the public in proportion as the sovereigns were exported – which was the main cause of the dreadful commercial catastrophe which ensued, and from the effects of which, after two years of unexampled suffering, the nation has scarcely yet begun to recover. But what we wish to draw the public attention to is this. The greatest importation of foreign grain ever known, into the British islands, before the corn laws were repealed, was in the year 1839, when, in consequence of three bad harvests in succession, 4,000,000 quarters in round numbers were imported. The average importation had been steadily diminishing before that time, since the commencement of the century: in the five years ending with 1835, it was only 381,000 quarters. But since the duties have become nominal, since the 1st February in this year, the importation has become so prodigious that it is going on at the rate of FIFTEEN MILLIONS of quarters a-year, or a full fourth of the national consumption, which is somewhat under sixty millions. This is in the face of prices fallen to 44s. 9d. for the quarter of wheat, and 18s. the quarter of oats! We recommend the Table below, taken from the columns of that able free-trade journal, the Times– showing the amount of importation for the month ending April 5, 1849, when wheat was at 45s. a-quarter – to the consideration of those well-informed persons who expect that low prices will check, and at last stop importation. It shows decisively that even a very great reduction of prices has not that tendency in the slightest degree. The importation of grain and flour is going on steadily, under the present low prices, at the rate of about 15,000,000 quarters a-year.18

The reasons of this continued and increasing importation, notwithstanding the lowness of prices, is evident, and was fully explained by the protectionists before the repeal of the corn laws took place, though the free-traders, with their usual disregard of facts when subversive of a favourite theory, obstinately refused to credit it. It is this. The price of wheat and other kinds of grain, in the grain-growing countries, especially Poland and America, is entirely regulated by its price in the British islands. They can raise grain in such quantities, and at such low rates, that everything depends on the price which it will fetch in the great market for that species of produce – the British empire. In Poland, the best wheat can be raised for 16s. a-quarter, and landed at any harbour in England at 25s. The Americans, out of the 250,000,000 quarters of bread stuffs which they raise annually, and which, if not exported, is in great part not worth above 10s. a-quarter, can afford, with a handsome profit to the exporting merchant, to send grain to England, however small its price may be in the British islands. However low it may be, it is much higher than with them – and therefore it is always worth their while to export it to the British market. If the price here is 40s., it will there be 28s. or 30s.; if 30s. here, it will not be more than 15s. or 20s. there. Thus the profit to be made by importation retains its proportion, whatever prices are in this country, and the motives to it are the same whatever the price is. It is as great when wheat is low as when it is high, except to the fortunate shippers, before the rise in the British islands was known on the banks of the Vistula or the shores of the Mississippi. Now that the duty on wheat is reduced to 1s. a-quarter, we may look for an annual importation of from 15,000,000 to 20,000,000 quarters – that is, from a fourth to a third of the annual subsistence, constantly, alike in seasons of plenty and of scarcity.

That the importation is steadily going on, appears by the following returns for the port of London alone, down to May, taken from the Morning Post of May 7: —

Entered for home consumption during the month ending —

– equal, if we take 3½ cwt. of flour to the qr. of wheat, to 2,200,700 qrs. of the latter. The importations of the first four months of the year are, therefore, nearly as great as they were during the whole of the preceding twelve months, the quantities duty paid in 1848 being, of wheat, 2,477,366 qrs., and of flour, 1,731,974 cwt.

The reason why young states, especially if they possess land eminently fitted for agricultural production, such as Poland and America, can thus permanently undersell older and longer established empires in the production of food, is simple, permanent, and of universal application, but nevertheless it is not generally understood or appreciated. It is commonly said that the cause is to be found in the superior weight of debts, public and private, in the old state. There can be no doubt that this cause has a considerable influence in producing the effect, but it is by no means the only or the principal one. The main cause is to be found in the superior riches of the old state, when compared with the young one, which makes money of less value, because it is more plentiful. The wants and necessities of an extended commerce, the accumulated savings of centuries of industry, at once require an extended circulation, and produce the wealth necessary to purchase it. The precious metals, and wealth of every sort, flow into the rich old state from the poor young one, for the same reason that corn, and wine, and oil, follow the same direction in obedience to the same impulse. That it is the superior riches, and not the debts or taxes, of England which render prices so high, comparatively speaking, in these islands, is decisively proved by the immense difference between the value of money, and the cost of living at the same time, in different parts of the same empire, subject to the same public and private burdens, – in London, for example, compared with Edinburgh, Aberdeen, and Lerwick. Every one knows that £1500 a-year will not go farther in the English metropolis than £1000 in the Scotch, or £750 in the ancient city of Aberdeen, or £500 in the capital of the Orkney islands. Whence this great difference in the same country, and at the same time? Simply, because money is over plentiful in London, less so in Edinburgh, and much less so in Aberdeen or Lerwick. The same cause explains the different cost of agricultural production in England, Poland, the Ukraine, and America. It is the comparative poverty, the scarcity of money, in the latter countries which is the cause of the difference. Machinery, and the division of labour, almost omnipotent in reducing the cost of the production of manufactured articles, are comparatively impotent in affecting the cost of articles of rude or agricultural produce. England, under a real system of free trade, would undersell all the world in its manufactures, but be undersold by all the world in its agricultural productions. If the national debt was swept away, and the whole taxes of Great Britain removed, the cost of agricultural production would not be materially different from what it now is. We shall be able to raise grain as cheap as the serfs of Poland, or the peasants of the Ukraine, when we become as poor as they are, but not till then. Under the free-trade system, however, the period may arrive sooner than is generally suspected, and the importation of foreign grain be checked by the universal pauperism and grinding misery of the country.

Assuming it, then, as certain that, under the free-trade system, the importation of grain is to be constantly from a third to a fourth of the annual consumption, the two points to be considered are, How is the national independence to be maintained, or incessant commercial crises averted, under the new system? These are questions on which it will become every inhabitant of the British islands to ponder; for on them, not only the independence of his country, but the private fortune of himself and his children, is entirely dependent. If so large a portion as a third or a fourth of the annual subsistence is imported almost entirely from three countries, Russia, Prussia, and America, how are we to withstand the hostility of these states? Prussia, in the long run, is under the influence of Russia, and follows its system of policy. The nations on whom we depend for so large a part of our food are thus practically reduced to two, viz., Russia and America – what is to hinder them from coalescing to effect our ruin, as they practically did in 1800 and 1811, against the independence of England? Not a shot would require to be fired, not a loan contracted. The simple threat of closing their harbours would at once drive us to submission. Importing a third of our food from these two states, to what famine-price would the closing of their harbours speedily raise its cost! The failure of £15,000,000 worth of potatoes in 1847 – scarce a twentieth part of the annual agricultural produce of these islands, which is about £300,000,000, – raised the price of wheat, in 1848, from 60s. to 110s. – what would the sudden stoppage of a third do? Why, it would raise wheat to 150s. or 200s. a-quarter – in other words, to famine-prices – and inevitably induce general rebellion, and compel national submission. After the lapse of fifteen centuries, we should again realise, after similar Eastern triumphs, the mournful picture of the famine in Rome, in the lines of the poet Claudian,19 from the stoppage of the wonted supplies of grain from the two granaries of the empire, Egypt and Libya, by the effect of the Gildonic war. But the knowledge of so terrible a catastrophe impending over the nation would probably prevent the collision. England would capitulate while yet it had some food left, on the first summons from its imperious grain-producing masters.

But supposing such a decisive catastrophe were not to arise, at least for a considerable period, how are commercial crises to be prevented from continually recurring under the new policy? How is the commercial interest to be preserved from ruin – from the operation of the system which itself has established? This is a point of paramount interest, as it directly affects every fortune in the kingdom, the commercial in the first instance, but also the realised and landed in the last; but, nevertheless, it seems impossible to rouse the nation to a sense of its overwhelming importance and terrible consequences. Experience has now decisively proved that the corn-growing states, upon whom we most depend for our subsistence, will not take our manufactures to any extent, though they will gladly take our sovereigns or bullion to any imaginable amount. The reason is, they are poor states, who are neither rich enough to buy, nor civilised enough to have acquired a taste for our manufactured articles, but who have an insatiable thirst for our metallic riches, the last farthing of which they will drain away, in exchange for their rude produce. The dreadful monetary crises of 1839 and 1848, it is well known, were owing to the drain upon our metallic resources, produced by the great grain importations of those years, in the latter of which above £30,000,000 of gold, probably a half of the metallic circulation, was at once sent headlong out of the country. Now, if an importation of grain to a similar amount is to become permanent, and an export of the precious metals to a corresponding degree to go on year after year, how, in the name of wonder, is a perpetual repetition of similar disasters to be prevented?

We could conceive, indeed, a system of paper currency which might in a great degree, if not altogether, prevent these terrible disasters. If the nation possessed a circulation of bank-notes capable of being extended in proportion as the metallic circulation was withdrawn by the exchanges of the commerce in grain, as was the law during the war, the industry of the country might be vivified and sustained during the absence of the precious metals, and their want be very little, if at all, experienced. But it is well known that not only is there no provision made by law, or the policy of government, for an extension of the paper circulation when the metallic currency is withdrawn, but the very reverse is done. There is a provision, and a most stringent and effectual one, made for the contraction of the currency at the very moment when its expansion is most required, and when the national industry is threatened with starvation in consequence of the vast and ceaseless abstraction of the precious metals which free trade in grain necessarily establishes. When free trade is sending gold headlong out of the country, to buy food, Sir Robert Peel's law sends the bank-notes, public and private, back into the banker's coffers, and leaves the industry of the country without either of its necessary supports! Beyond all question, it is the double operation of free trade in sending the sovereigns in enormous quantities out of the country, and of the monetary laws, in contracting the circulation of paper in a similar degree, and at the same time, which has done all the mischief, and produced that widespread ruin which has now overtaken nearly all the interests – but most of all the commercial interests – in the state. That ruin is easily explained, when it is recollected what government has done by legislative enactment, on free-trade principles, during the last five years.

1. They first, by the Acts of 1844 and 1845, restricted the paper circulation of the whole empire, including Ireland, to £32,000,000 in round numbers. For every note issued, either by the Bank of England or private banks, above that sum, they required these establishments to have sovereigns in their coffers.

2. Having thus restricted the currency, by which the industry of the country was to be paid and supplied, to an amount barely sufficient for its ordinary wants, they next proceeded to encourage to the greatest degree railway speculation, and pass bills through parliament requiring an extraordinary expenditure, in the next four years, of £333,000,000 sterling.

3. Having thus contracted the currency of the nation, and doubled its work, they next proceeded to introduce, in 1846 and the two following years, the free-trade system, under the operation of which our specie was sent out of the country in enormous quantities, in exchange for food, and by the operation of the law the paper proportionally contracted.20

4. When this extraordinary system of augmenting the work of the people, at the time the currency which was to sustain it was withdrawn, had produced its natural and unavoidable effects, and landed the nation, in October 1847, in such a state of embarrassment as rendered a suspension of the law unavoidable, and induced a commercial crisis of unexampled severity and duration, the authors of the monetary measures still clung to them as the sheet-anchor of the state, and still upheld them, although it is as certain as any proposition in Euclid, that, combined with a free trade in grain, they must produce a constant succession of similar catastrophes, until the nation, like a patient exhausted by repeated shocks of apoplexy, perishes under their effects.

It may be doubted whether the annals of the world can produce another example of insane and suicidal policy on so great a scale as has been exhibited by the government of England of late years, in its West India measures, and the simultaneous establishment of free trade and fettered currency, and a railway mania, in the heart of the empire.

The effect of these measures upon the internal state of the empire has been beyond all measure dreadful, and has far exceeded the worst predictions of the protectionists upon their inevitable effect. Proofs on this subject crowd in on every side, and all entirely corroborative of the prophecies of the protectionists, and subversive of all the prognostics of the free-traders. It was confidently asserted by them that their system would immensely increase our foreign trade, because it would enrich the foreign agriculturists from whom we purchased grain, and who would take our manufactures in exchange; and what has been the result, after free-trade principles have been in full operation for three years? Why, they have stood thus: —