полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 64 No. 396 October 1848

"We are not surprised that Irish juries will not convict Irish rebels. It is too much to expect that they should do so, even when fully convinced of, and indignant at, their guilt. It would be almost too much to ask from Englishmen. Government have a right to call upon jurors to do their duty, under ordinary circumstances and in ordinary times. In like manner, Government has a right to call upon all citizens to come forward, and act as special constables, in all cases of civil commotion. But it has no right to send them forth, unexercised and unarmed, to encounter an organised and disciplined force, provided with musket and artillery: that is the business of regular troops. In like manner, Government has no right to expect jurors to act at the hazard of their lives and property. The law never contemplated that serving on a jury should be an office of danger. When it becomes such, other agencies must be brought into operation.

"It will not suffice to the Government to have acted with such skill and spirit as to have rendered abortive a formidable and organised rebellion. It must crush the rebellious spirit and the rebellious power. This can never be done by the means of juries. Punishment, to be effectual, must fall with unerring certainty on every one concerned in the crime. They must be made to feel that no legal chicanery, no illegitimate sympathy, can avail to save them. The British nation, we are sure, will never endure that men who have been guilty of such crimes as the Irish felons should escape punishment, and be again let loose on society, to mock and gibe at the impotence of power. Any termination of the crisis would be preferable to one so fatal and disgraceful." —Economist, Sept. 12, 1848.

These articles, emanating from such sources, induce us to hope that the long-protracted distractions of Ireland are about to be brought to a close; and that, after having been for above half a century the battle-field of English faction, or cursed with Liberal English sympathy, and its inevitable offspring, Irish agitation and mendacity – the real secret of its sufferings has been brought to light; and that, by being governed in a manner suitable to its character and circumstances, it will at length take its place among the really civilised nations of the world, and become fit for the exercise of those privileges which, prematurely conceded, have proved its ruin.

One circumstance induces the hope that this anticipation maybe realised, and that is, the highly honourable part which the Irish enrolled in the police have taken in the late disturbances; the fidelity of all the Irish in the Queen's service to their colours; and the general pacific conduct which has, with a few exceptions, been observed by the numerous Hibernians settled in Great Britain during the late disturbances. The conduct of the Irish police, in particular, has been in all respects admirable; and it is net going too far to assert, that to their zeal, activity, and gallantry, the almost bloodless suppression of the insurrection is mainly to be ascribed. The British army does not boast a more courageous body of men than the Irishmen in its ranks; and it is well known that, after a time, they form the best officers of a superior kind for all the police establishments in the kingdom. Although the Irish in our great towns are often a very great burden, especially when they first come over, from the vast number of them who are in a state of mendicity, and cannot at first get into any regular employment, yet when they do obtain it, they prove hardworking and industrious, and do not exhibit a greater proportion of crime than the native British with whom they are surrounded. The Irish quickness need be told to none who have witnessed the running fire of repartee they keep up from the fields with travellers, how rapid soever, on the road; their genius is known to all who are familiar with the works of Swift and Goldsmith, of Burke and Berkeley. Of one thing only at present they are incapable, and that is, self-government. One curse, and one curse only, has hitherto blasted all their efforts at improvement, and that is, the abuse of freedom. One thing, and one thing only, is required to set them right, and that is, the strong rule suited to national pupilage. One thing, and one thing only, is required to complete their ruin, and that is, repeal and independence. An infallible test will tell us when they have become prepared for self-government, and that is, when they have ceased to hate the Saxon – when they adopt his industry, imitate his habits, and emulate his virtues.

We have spoken of the French and the Irish, and contrasted, not without some degree of pride, their present miserable and distracted state with the steady and pacific condition of Great Britain, during a convulsion which has shaken the civilised world to its foundation. But let it not be supposed that France and Ireland alone have grievances which require redress, erroneous policy which stands in need of rectification. England has its full share of suffering, and more than its deserved share of absurd and pernicious legislation. But it is the glory of this country that we can rectify these evils by the force of argument steadily applied, and facts sedulously brought forward, without invoking the destructive aid of popular passions or urban revolutions. We want neither Red Republicans nor Tipperary Boys to fight our battles; we neither desire to be intrenched behind Parisian barricades nor Irish non-convicting juries; we neither want the aid of Chartist clubs, with their arsenals of rifles, nor Anti-corn-law Leagues, with their coffers of gold. We appeal to the common sense and experienced suffering of our countrymen – to the intellect and sense of justice of our legislators; and we have not a doubt of ultimate success in the greatest social conflict in which British industry has ever been engaged.

We need not say that we allude to the Currency – that question of questions, in comparison of which all others sink into insignificance; which is of more importance, even, than an adequate supply of food for the nation; and without the proper understanding of which all attempts to assuage misery or produce prosperity, to avert disaster or induce happiness, to maintain the national credit or uphold the national independence, must ere long prove nugatory. We say, and say advisedly, that this question is of far more importance than the raising of food for the nation; for if their industry is adequately remunerated, and commercial catastrophes are averted from the realm, the people will find food for themselves either in this or foreign states. Experience has taught us that we can import twelve millions of grain, a full fifth of the national subsistence, in a single year. But if the currency is not put upon a proper footing, the means of purchasing this grain are taken from the people– their industry is blasted, their labour meets with no reward – and the most numerous and important class in the community come to present the deplorable spectacle of industrious worth perishing of hunger, or worn out by suffering, in the midst of accumulated stores of home-grown or foreign subsistence.

The two grand evils of the present monetary system are, that the currency provided for the nation is inadequate in point of amount, and fluctuating in point of stability.

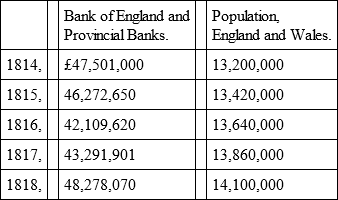

That it is inadequate in point of amount is easily proved. In the undermentioned years, the aggregate of notes in circulation in England and Wales, without Scotland and Ireland, was as follows16: —

Including the Scotch and Irish notes, at that period about £12,000,000, the notes in circulation were about £60,000,000, and the inhabitants of Great Britain 14,000,000; of the two islands about 19,000,000 – or about £3, 4s. a head.

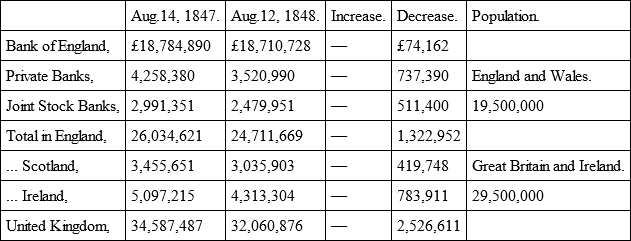

In the year 1848, thirty years afterwards, when the population of the empire had risen to 29,000,000, the exports had tripled, and the imports and shipping had on an average more than doubled, the supply of paper issued to the nation stood thus: —

Notes.

Thus showing a decrease of £1,322,952 in the circulation of notes in England, and a decrease of £2,526,611 in the circulation of the United Kingdom, when compared with the corresponding period last year.17—Times, Aug. 29, 1848.

Thus, in the last thirty years, the population of Great Britain and Ireland has increased from 19,000,000 to 29,500,000; while its currency in paper has decreased from £60,000,000 to £32,000,000. Above fifty per cent has been added to the people, and above a hundred per cent to their transactions, and the currency by which they are to be carried on has been contracted fifty per cent. Thirty years ago, the paper currency was £3, 5s. a head; now it is not above £1, 5s. a head! And our statesmen express surprise at the distress which prevails, and the extreme difficulty experienced in collecting the revenue! It is no wonder, in such a state of matters, that it is now more difficult to collect £52,000,000 from 29,000,000 of people, than in 1814 it was to collect £72,000,000 from 18,000,000.

The circulation, it is particularly to be observed, is decreasing every year. It was, in August 1848, no less than £2,500,000 less than it was in August 1847, though that was the August between the crisis of April and the crisis of October of that year. And this prodigious and progressively increasing contraction of the currency, and consequent drying up of credit and blasting of industry, is taking place at the precise time when the very legislators who have produced it have landed the nation in the expenditure, in three years, of £150,000,000 on domestic railways, independent of a vast and increasing import trade, which is constantly draining more and more of our metallic resources out of the country! Need it be wondered at that money is so tight, and that railway stock in particular exhibits, week after week, a progressive and most alarming decline.

But, say the bullionists, if we have taken away one-half of your paper, we have given you double the former command of sovereigns; and gold is far better than paper, because it is of universal and permanent value. There can be no doubt that the gold and silver coinage at the Mint has been very much augmented since paper was so much withdrawn; and the amount in circulation now probably varies in ordinary times from £40,000,000 to £45,000,000. There can be as little doubt that the circulation, on its present basis, is capable of fostering and permitting the most unlimited amount of speculations; for absurd adventures never were so rife in the history of England, not even in the days of the South Sea Company, as in 1845, the year which immediately followed Sir R. Peel's new currency measures, by which these dangers were to be for ever guarded against. It is no wonder it was so; for the bill of 1844 aggravates speculation as much in periods of prosperity, as it augments distress and pinches credit in times of adversity. By compelling the Bank of England, and all other banks, to hold constantly in their coffers a vast amount of treasure, which must be issued at a fixed price, it leaves them no resource for defraying its charges but pushing business, and getting out their notes to the uttermost. That was the real secret of the lowering of the Bank of England's discounts to 3 and 2-1/2 per cent in 1845, and of the enormous gambling speculations of that year, from the effects of which the nation is still so severely suffering.

But as gold is made, under the new system, the basis of the circulation beyond the £32,000,000 allowed to be issued in the United Kingdom on securities, what provision does it make for keeping the gold thus constituted the sole basis of two-thirds of the currency within the country? Not only is no such provision made, but every imaginable facility is given for its exportation. Under the free-trade system, our imports are constantly increasing in a most extraordinary ratio, and our exports constantly diminishing. Since 1844, our imports have swelled from £75,000,000 to £90,000,000, while our exports have decreased from £60,000,000 to £58,000,000, of which only £51,000,000 are British and Irish exports and manufactures.18 How is the balance paid, or to be paid? In cash: and that is the preparation which our legislators have made for keeping the gold, the life-blood of industry and the basis of two-thirds of the circulation, in the country. They have established a system of trade which, by inducing a large and constant importation of food, for which scarcely any thing but gold will be taken, induces a constant tendency of the precious metals outwards. With the right hand they render the currency and credit beyond £32,000,000 entirely dependent on keeping the gold in the country, and with the left hand they send it headlong out of the country to buy grain. No less than £33,000,000 were sent out in this way to buy grain in fifteen months during and immediately preceding the year 1847. They do this at the very time when, under bills which themselves have passed, and the railways which themselves have encouraged, £150,000,000 was in the next three years to be expended on the extra work of railways! Is it surprising that, under such a system, half the wealth of our manufacturing towns has disappeared in two years; that distress to an unheard-of extent prevails every where; and that the Chancellor of the Exchequer has been obliged to borrow £10,000,000, in the last and present session of Parliament, during general peace?

Let it not be supposed this evil has passed away. It is in full vigour at the present moment. It will never pass away as long as free trade and a fettered currency coexist in this country. The disastrous fact has been revealed by the publication of the Board of Trade returns, that while, during the first six months of this year, our imports have undergone little diminution, our exports have sunk £4,000,000 below the corresponding months in last year. In May alone, the decrease was £1,122,000; in April, £1,467,000.19 Beyond all doubt our exports, this year, of British produce and manufactures, will sink to £45,000,000, while our imports will reach at least £85,000,000! How is the balance paid? In Specie! And still the monetary laws remain the same, and for every five sovereigns above £32,000,000 lent out, a note must be drawn in! It may be doubted whether a system so utterly absurd and ruinous ever was established in any nation, or persevered in with such obstinacy after its pernicious effects had been ascertained by experience.

The manner in which these disastrous effects resulted, necessarily and immediately, from the combined operation of the bills of 1819 and 1844, is thus clearly and justly stated by Mr Salt, in his late admirable letter to Sir R. Peel on the subject.

"The potato crop failed, and an importation of food became necessary; the food was imported at a cost not exceeding one half per cent on the national wealth. It might have been paid for in goods or in gold, and the limit of the loss would have been the amount paid – a sum too insignificant, compared to the national resources, to have been perceptible – and the national industry could have replaced it in a few weeks.

"But the bill of 1819 had made gold the basis of our whole system; and, therefore, when the gold was exported to pay for the food, the whole system was broken up; and the bill provides that this calamity shall in every case be added to that of a bad harvest; that the abstraction of an infinitesimal part of our money shall destroy our whole monetary system; that the purchase of a small quantity of food shall cause an immense quantity of starvation, by destroying the means of distributing the food, and employing labour. If this were the only evil of the bill, its existence ought not to be tolerated an hour.

"Instead of placing the national credit and solvency on the broad and indestructible basis of the national industry and wealth, you have placed all the great national interest on gold, the narrowest and most shifting, and therefore the most unfit, basis it was possible to choose. You could not have done worse.

"The gold being in quantity perfectly unequal to effect the exchanges needful for the existence of society, an immense and disproportioned superstructure of paper money and credit became a compulsory result, and a certain cause of perpetually recurring ruin.

"In framing the bill of 1819 you do not appear to have had a suspicion of this consequence; but in 1844, after an interval of a quarter of a century, this much seems to have dawned obscurely in your mind; but, alas! what was your remedy? – enlarging and securing the too narrow and shifting basis? Not at all; you crippled and limited the superstructure. You left us subject to the whole of your original error, and provided a new one!

"The bill of 1844 provides that, in proportion as the gold money shall disappear, the paper money shall disappear also! Out of the money thus doubly reduced, the unhappy people are compelled to pay unreduced taxes; and out of the inadequate remnant to discharge unreduced debts, and to provide for the unreduced necessities of their respective stations. So the leaven of the law works its way through all society. The payments cannot be made out of these reduced means, the loss of the credit follows the loss of the money; the means of exchange, employment, and consumption are destroyed, and the world looks with amazement on the consummation of your work – the wealthiest nation in the world withering up under the blight of a universal insolvency; an abundance of all things beyond compute, and a misery and want beyond relief.

"The sole aim of your bill has been to convert paper money into gold. I have shown how signally you have failed in this one object, always excepting your special claim of converting £48,000,000 of paper money into £15,000,000 of gold, for which mutation I suspect few will thank you. In all other respects, the whimsicality of your fate has been to establish a universal inconvertibility. Labour cannot be converted into wages, East India estates, West India estates, railway shares, sugar, rice, cotton goods, &c.; in short, all things are inconvertible except gold. There has been nothing like it since the days of Midas.

"The facts, sir, are of your creation, not of mine. I cannot alter or disguise them. You have had confided to your administration, by our illustrious sovereign, this most powerful state, of almost unlimited extent and fertility – a people unrivalled in their knowledge, caution, skill, and energy, possessed of unlimited means of creating wealth, and out of all these elements of human happiness your measures have produced a chaos of ruin, misery, and discontent. You can scarcely place your finger on the map, and mark a spot in this vast empire where all the elements of prosperity do not exist abundantly; you cannot point out one where you have not produced results of ruin. Every resource is paralysed, every interest deranged; the very empire is threatened with dissolution. The Canadas, the West Indies, and Ireland, are threatening secession, and England has to be garrisoned against its people as against a hostile force; the very loyalty of English hearts is beginning to turn into disaffection. Review once more these vast resources, and these wretched results, and I trust you will not make the fatal opinion of your life the only one to which you will persist in adhering."

This is language at once fearless, but measured – cutting, but respectful, which, on such an emergency, befits a British statesman. There is no appeal to popular passions, no ascribing of unworthy motives, no attempt to evade inquiry by irony; facts, known undeniable facts, are alone appealed to. Inferences, clear, logical, convincing, are alone drawn. If such language was more frequent, especially in the House of Commons, the plague would soon be stayed, and its former prosperity would again revisit the British Empire.

In opposition to these damning facts, the whole tactics of the bullionists consist in recurring to antiquated and childish terrors. They call out "Assignats, assignats, assignats!" – they seek to alarm every holder of money by the dread of its depreciation. They affect to treat the doctrine of keeping a fair proportion between population, engagements, and currency, as a mere chimera. In the midst of the deluge, they raise the cry of fire; when wasting of famine, they hold out to us the terrors of repletion; when sinking from atrophy on the way-side, they strive to terrify us by the dangers of apoplexy. The answer to all this tissue of affectation and absurdity is so evident, that we are almost ashamed to state it. We all know the dangers of assignats; we know that they are ruinous when issued to any great extent. So also we know the dangers of apoplexy and intoxication; but we are not on that account reconciled to a regimen of famine and starvation. We know that some of the rich die of repletion, but we know that many more of the poor die of want and wretchedness. We do not want to be deluged with inconvertible paper, which has been truly described as "strength in the outset, but weakness in the end;" but neither do we desire to be starved by the periodical abstraction of that most evanescent of earthly things, a gold circulation. Having the means, from our own immense accumulated wealth, of enjoying that first of social blessings, an adequate, steady, and safe currency, we do not wish to be any longer deprived of it by the prejudices of theorists, the selfishness of capitalists, or the obstinacy of statesmen. Half our wealth, engaged in trade and manufactures, has already disappeared, under this system, in two years; we have no disposition to lose the remaining half.

The duty on wheat now is only five shillings a quarter; in February next it will fall to one shilling a quarter, and remain fixed at that amount. The importation of grain, which was felt as so dreadful a drain upon our metallic resources in 1847, may, under that system, be considered as permanent. We shall be always in the condition in which the nation is when three weeks' rain has fallen in August. Let merchants, manufacturers, holders of funded property, of railway stock, of bank stock, reflect on that circumstance, and consider what fate awaits them if the present system remains unchanged. They know that three days' rain in August lowers the public funds one, and all railway stock ten per cent. Let them reflect on their fate if, by human folly, an effect equal to that of three weeks' continuous fall of rain takes place every year. Let them observe what frightful oscillations in the price of commodities follow the establishing by law a fixed price for gold. Let them ponder on the consequences of a system which sends twelve or fifteen millions of sovereigns out of the country annually to buy grain, and contracts the paper remaining in it at the same time in the same proportion. Let them observe the effect of such a system, coinciding with a vast expenditure on domestic railways. And let them consider whether all these dreadful evils, and the periodical devastation of the country by absurd speculation and succeeding ruin, would not be effectually guarded against, and the perils of an over-issue of paper also prevented, by the simple expedient of treating gold and silver, the most easily transported and evanescent of earthly things, like any other commodity, and making paper always payable in them, but at the price they bear at the moment of presentment. That would establish a mixed circulation of the precious metals and paper, mutually convertible, and allow an increased issue of the latter to obviate all the evils flowing from the periodical abstractions of the former. To establish the circulation on a gold basis alone, in a great commercial state, is the same error as to put the food of the people in a populous community on one root or species of grain. Ireland has shown us, in the two last years, what is the consequence of the one – famine and rebellion; England, of the other – bankruptcy and Chartism.

BYRON'S ADDRESS TO THE OCEAN