полная версия

полная версияBirds and All Nature, Vol. V, No. 3, March 1899

Hares generally feed at night, lying in their forms in some bush or copse during the greater part of the day; rabbits, on the contrary, generally remain in the warmest corner of the burrow during the dark hours. The food of the hare consists of all kinds of vegetables similar in nature to cabbage and turnips, which are favorite dainties with it; it is also especially fond of lettuce and parsley.

The great speed of the hare in running is chiefly due to the fact that the hind legs are longer than the fore. This is also the reason why it can run better up hill than down. Generally it utters a sound only when it sees itself in danger. This cry resembles that of a little child, being a shrill scream or squeak.

Among the perceptive senses of the hare, hearing is best developed; the smell is fairly keen, but sight is rather deficient. Prudence and vigilance are its most prominent characteristics. The slightest noise – the wind rustling in the leaves, a falling leaf – suffices to excite its attention and awaken it from sleep. Dietrich Aus Dem Winckell says that the greatest vice of the hare is its malice, not because it expresses it in biting and scratching, but because it often proves its disposition in the most revolting manner, the female by denying her maternal love, and the male by his cruelty to the little leverets.

It is said that captive hares are easily tamed, become readily used to all kinds of nourishment usually fed to rabbits, but are very delicate and apt to die. If they are fed only on hay, bread, oats, and water, and never anything green, they live longer. A tame hare, in the possession of Mr. Fuchs in Wildenberg, which slept and ate with his dogs, ate vegetable food only in default of meat – veal, pork, liver, and sausage causing it to go into such raptures that it would execute a regular dance to get at these dainties.

Besides the flesh, which as food is justly esteemed, the fur of the hare is also put to account. The skin is deprived of its hair, tanned and used in the manufacture of shoes, of one kind of parchment, and of glue; the hair is used in the manufacture of felt.

Mark Twain, in his "Roughing It," gives this humorous and characteristic description of the jack rabbit:

"As the sun was going down, we saw the first specimen of an animal known familiarly over two thousand miles of mountain and desert – from Kansas clear to the Pacific ocean – as the 'jackass-rabbit.' He is well named. He is just like any other rabbit, except that he is from one-third to twice as large, has longer legs in proportion to his size, and has the most preposterous ears that ever were mounted on any creature but a jackass. When he is sitting quiet, thinking about his sins, or is absent-minded, or unapprehensive of danger, his majestic ears project above him conspicuously; but the breaking of a twig will scare him nearly to death, and then he tilts his ears back gently, and starts for home. All you can see then, for the next minute, is his long form stretched out straight, and 'streaking it' through the low sage-bushes, head erect, eyes right, and ears just canted to the rear, but showing you just where the animal is, just the same as if he carried a jib. When he is frightened clear through, he lays his long ears down on his back, straightens himself out like a yardstick every spring he makes, and scatters miles behind him with an easy indifference that is enchanting. Our party made this specimen 'hump himself.' I commenced spitting at him with my weapon, and all at the same instant let go with a rattling crash. He frantically dropped his ears, set up his tail, and left for San Francisco at lightning speed. Long after he was out of sight we could hear him whiz."

C. C. M.DESTRUCTION OF BIRD LIFE

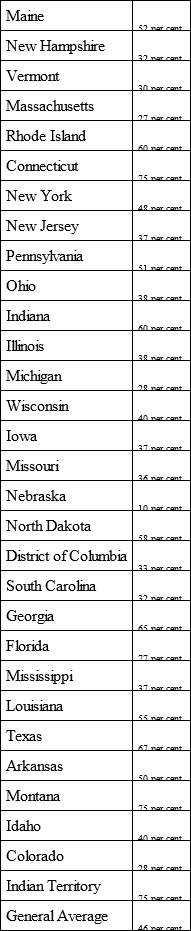

STEPS have been taken under the direction of the New York zoölogical society to ascertain, as nearly as possible, to what extent the destruction of bird life has been carried in this country and the result of the investigation is given in its second annual report, recently published. Replies to questions on the subject were received from over two hundred competent observers in the different states and territories, and the following table is believed to give a fair, certainly not exaggerated, idea of the loss of bird life within the past decade and a half.

The following are the percentages of decrease throughout the states mentioned, during the last fifteen years, according to the reports:

At least three-fifths of the total area of the United States is represented by the thirty states and territories above named, and the general average of decrease of bird life therein is 46 per cent. These figures are startling indeed and should arouse everyone to the gravity of the situation which confronts us. It requires but little calculation to show that if the volume of bird life has suffered a loss of 46 per cent. within fifteen years, at this rate of destruction practically all birds will be exterminated in less than a score of years from now.

WE BELIEVE IT

THERE is no being so homely, none so venomous, none so encased in slime or armed with sword-like spines, none so sluggish or so abrupt in behavior, that it cannot win our favor and admiration – the more, the better we know it. However it may be in human society, with the naturalist it is not familiarity which breeds contempt. On the contrary, it has been said, with every step of his advancing knowledge he finds in what was at first indifferent, unattractive, or repulsive, some wonder of mechanism, some exquisite beauty of detail, some strangeness of habit. Shame he feels at having so long had eyes which seeing saw not; regret he feels that the limits of his life should be continually contracting, while the boundaries of his science are always expanding; but so long as he can study and examine, he is so far contented and happy.

THE PINEAPPLE

THIS tropical fruit is so-called from its resemblance in form and appearance to the cones of some species of pine. Its botanical name in most general use is Ananassa sativa, but some botanists who do not regard it as distinct from Bromelia, call it B. ananas. The Bromeliaceæ, to which it belongs, are a small family of endogenous plants, quite closely related to the canna, ginger, and banana families, and differing from them in having nearly regular flowers and six stamens, all perfect. As the pineapple has become naturalized in parts of Asia and Africa, its American origin has been disputed, but there is little doubt that it is a native of Brazil, and perhaps some of the Antilles, now a part of the domain of the United States. This fruit is a biennial, with the habit of the Aloe, but with much thinner leaves. In cultivation it early produces seeds but, in ripening, the whole flower cluster undergoes a remarkable change; all parts become enormously enlarged, and when quite ripe, fleshy and very succulent, being pervaded by a saccharine and highly flavored juice. Instead of being a fruit in the strict botanical sense of the term, it is an aggregation of accessory parts, of which the fruit proper forms but a very small portion.

The first pineapples known in England were sent as a present to Oliver Cromwell; the first cultivated in that country were raised in about 1715, though they were grown in Holland in the preceding century. The successful cultivation of the fruit was early considered one of the highest achievements in horticulture, and the works of a few years ago are tediously elaborate in their instructions; but the matter has been so much simplified that anyone who can command the proper temperature and moisture may expect success.

For many years pineapples have been taken from the West Indies to England in considerable quantities, but the fruit is so inferior to that raised under glass that its cultivation for market is prosecuted with success. The largest fruit on record, as the produce of the English pineries, weighed fourteen pounds and twelve ounces. Better West Indian pineapples are sold in our markets than in those of England, as we are nearer the places of growth.

The business of canning this fruit is largely pursued at Nassau, New Providence, whence many are also exported whole. The business has grown greatly within a few years, and now that the United States is in possession of the West Indian islands, exportations may be expected to increase and the demand satisfied.

More than fifty varieties of the pineapple are enumerated. The plant is evidently very variable, and when South America was first visited by Europeans, they found the natives cultivating three distinct species. Some varieties, with proper management, will be in fruit in about eighteen months from the time the suckers are rooted. The juice of the pineapple is largely used in flavoring ices and syrups for soda-water; the expressed juice is put into bottles heated through by means of a water bath and securely corked while hot. If stored in a cool place it will preserve its flavor perfectly for a year. The unripe fruit is very acrid, and its juice in tropical countries is used as a vermifuge. The leaves contain an abundance of strong and very fine fibers, which are sometimes woven into fabrics of great delicacy and lightness.

Nor is it every apple I desire;Nor that which pleases every palate best;'Tis not the lasting pine that I require,Nor yet the red-cheeked greening I request,Nor that which first beshrewed the name of wife,Nor that whose beauty caused the golden strife.No, no! bring me an apple from the tree of life.C. C. M.LITTLE BUSYBODIES

BELLE P. DOWNEYONE'S own observation tends to confirm the wonderful stories told by naturalists about ants. They have a claim to rank next to man in intelligence.

Seven or eight ants once attempted to carry a wasp across the floor. In the course of the journey they came to a crevice in a plank caused by a splinter which had been torn off. After repeated attempts to cross this deep ravine all the ants abandoned the task as hopeless except one who seemed to be the leader of the enterprise. He went on a tour of investigation, and soon found that the crevice did not extend very far in length. He then went after the retreated ants. They obeyed the summons and returned, when all set about helping to draw the wasp around the crevice. This little incident proves the ant is possessed of the power of communicating its wishes to others. Ants have been seen to bite off the legs of a cockroach in order to get it into the narrow door of their nest. The brain of ants is larger in proportion to their size than that of any other insect. Naturalists think that they have memory, judgment, experience, and feel hatred and affection for their kind. They are valorous, pugnacious, and rapacious, but also inclined to be helpful as they assist each other at their toilet. They have a peculiarity among insects of burying their dead. It is a curious fact that the red ants, which are the masters, never deposit their dead by the side of their black slaves, thus seeming to show some idea of caste.

Ants yawn, sleep, play, work, practice gymnastics, and are fond of pets, such as small beetles, crickets, and cocci, which they entertain as guests in their homes.

Indeed, ants are social, civilized, intelligent citizens of successfully governed cities. Even babies are claimed by the state. Their government is a happy democracy where the queen is "mother" but not ruler, and where the females have all the power. The queen is highly honored and at death is buried with magnificence. In her devotion to her lot in life she pulls off her glittering wings and becomes a willing prisoner in the best room of a house of many apartments. Here she is cared for by devoted followers who polish her eggs, carry them upward to the warmth of the sun in daytime, and back to the depths of the habitation to protect them from the chill of night. These eggs are so small as scarcely to be seen by the eye alone. They are bright and smooth, without any division. It is very strange, but these eggs will not develop into larvæ unless carefully nursed. This is effected by licking the surface of the eggs. Under the influence of this process they mature and produce larvæ. The larvæ are fed, like young birds, from the mouths of the nurses. When grown they spin cocoons and at the proper time the nurses help them out by biting the cases. The next thing the nurses do is to help them take off their little membranous shirts. This is done very gently. The youngsters are then washed, brushed, and fed, after which the teachers educate them as to their proper duties.

It is astonishing how many occupations are followed by these little busy-bodies whose size and weakness are made up for by their swiftness, their fineness of touch, the number of their eyes and a powerful acid which they use in self-defense. Their jaws are so much like teeth that they serve for cutting, while their antennæ are useful for measurement, and their front feet serve as trowels with which to mix and spread mortar. Ants may be said to have the following occupations: Housewives, nurses, teachers, spinners, menials, marauders, soldiers, undertakers, hunters, gardeners, agriculturalists, architects, sculptors, road makers, mineralogists, and gold miners.

Ants keep cows – the aphides – for which they sometimes build stables and place in separate stalls from the cocci, which they also use. They make granaries where they store ant rice. If the grain begins to sprout they are wise enough to cut off the sprout. If it gets wet they have often been seen carrying it up to the sunshine to dry and thus prevent sprouting. The honey-ant is herself a storehouse of food in case of famine. This kind of ant has a distension of the abdomen in which honey is stored by the workers for cases of need. They inject the honey into the mouth of the ant. When it is needed she forces it up to her lips by means of the muscles of the abdomen. It is said that the Mexicans like to culture honey ants and eat the honey themselves.

The leaf-cutting ant is the gardener. It is devoted to growing mushrooms or at least a kind of fungi of which it is fond. This accounts for the beds of leaves it carries to its nest, on which the fungi develop.

The Roman naturalist, Pliny, gives an account of some ants in India which extract gold from mines during the winter. In the summer, when they retire to their holes to escape the heat, the people steal their gold. McCook has found that we have ants who are mineralogists, as they cover their hill with small stones, bits of fossils and minerals, for which they go down like miners more than a yard deep into the earth.

That some kinds of ants are architects has been clearly proven, for an observer saw an ant architect order his workmen to alter a defective arch, which they did, apparently to suit his views of how arches should be constructed!

The ants who act as sculptors work in wood. The red ants of the forest build storied houses in trees with pillars for support. There is a little brown ant which makes a house forty stories high; half the rooms are below ground. There are pillars, buttresses, galleries, and various rooms with arched roofs. This ant works in clay. If her material becomes too dry she is compelled to wait for moisture.

The blind ant is a remarkable builder. She makes long galleries above ground. She does not use cement as some ants do, so she builds rapidly and her structure is flimsy.

The Saiiva ants of Brazil are skillful masons. They construct chambers as large as a man's head that have immense domes, and outlets seventy yards long. The Brazilians say that the Indians, in cases of wounds, when it was necessary to close them as with stitching, used the jaws of the Saiiva ant. The ant was seized by the body and placed so that the mandibles were one on each side of the cut. Then, when pressed against the flesh, the ant would close the mandibles and unite the two sides of the cut as firmly as a good stitch would do it. A quick twist of the ant's body separated it from the head. After a few days the heads were removed with a knife and the operation was complete.

In view of this we are tempted to say that ants are also surgeons, but die themselves instead of having their patients do so!

A friend who has lived long in Brazil tells me that the Saiiva ants are so large the nuns in the convents use their bodies to dress as dolls, making them represent soldiers, brides and grooms, and so forth.

One species of ants do nothing except capture slaves. These are not able to make their own nests, to feed their larvæ, or even to feed themselves, but are so helpless they would die if neglected by their servants. There are three species that keep slaves, but these are not the only ones who go to war, as the usually peaceful agricultural ants sometimes get short of seed and go forth to plunder each other's nests.

It is stated that a thousand species of ants are known. No doubt there is much of interest about each kind. The "Driver Ant" is so choice of time and labor that, when building its covered roads, if a crevice in a rock or a shady walk is reached, it utilizes these, then continues arching its path as before. If a flood comes these ants form into large balls with the weak ones in the middle, the stronger on the outside, and so swim on the water.

The ant benefits man by acting as a scavenger, by turning up the subsoil, and in various other ways. But flowers prefer the visits of moths and butterflies; as ants are of no service to them in scattering pollen, they do not wish them to get their honey. Some of the flowers have found out that ants, though so industrious by reputation, are lazy about getting out early in the morning for they dislike the dew very much. Hence by 9 o'clock these wary flowers have closed their doors. Others take the precaution to baffle ant visitors by holding an extra quantity of dew on the basins of their leaves, while still others exude a sticky fluid from their stems which glues the poor ants to the spot.

Campanula secretes her honey in a box with a lid. Cyclamen presents curved surfaces, while narcissus makes her tube top narrow. Other flowers have hooks and hairs by which the ants are warned to seek their honey elsewhere.

THE CHARITY OF BREAD CRUMBS

THE recent "cold wave," which with its severity and length has sorely tried the patience of Denver's citizens, has had its pleasant features. Perhaps chief of these has been the presence in our midst of scores of feathered visitors driven in, doubtless, by pangs of hunger, from the surrounding country.

Flocks of chickadees have flown cheerily about our streets, chirping and pecking industriously, as if to shame those of us who lagged at home because of zero temperature. They were calling to one another as we stood at the window watching them last Saturday morning.

Suddenly, down the street with the swiftness and fury of an Apache band, tore a group of small savages, each armed with a weapon in the shape of a stick about two feet long.

"What can those boys be playing?" inquired someone, and the answer to the question was found immediately as in horror she saw the sticks fly with deadly exactness into a group of the brave little snowbirds, and several of them drop lifeless or flutter piteously in the frozen street.

"How can boys be so heartless!" said the lady, rising in righteous wrath to reason with them.

"Thoughtless is nearer the truth," remarked a friend who had witnessed the scene. "Their hearts haven't been awakened on the bird question and it would be better to try and stir up their mothers and teachers than to fuss at the boys themselves."

But the Denver birds have plenty of friends and this has been proved many times during the past week.

At the surveyor-general's office Saturday morning there was held a large reception at which refreshments were served and the guests were largely house finches – small, brown birds with red about their throats. For a number of seasons the ladies and gentlemen employed there have spread a liberal repast several times each day upon the broad window ledges for these denizens of the air. The day being very cold, someone suggested that perhaps if the window were opened and seed scattered inside also, the birds would come in and get warm.

The feast was arranged with bits of apple, small cups of water, and a liberal supply of seed. And the invitation was accepted with alacrity. A swarm of busy little brown bodies jostled and twittered and ate ravenously of the viands provided, while thankful heads were raised over the water cups to let that cool liquid trickle down thirsty throats. It was a lovely sight and everyone in the room kept breathlessly still, but at last some noise outside alarmed the timid visitors and they whirred away in a small cloud, leaving but a remnant of the plenteous repast behind.

Several of the tiny creatures becoming puzzled flew about the room in distress, trying to get away, and one little fellow bumped his head violently against a glass and fell ignominiously into a spittoon. He was rescued and laid tenderly on the window sill to dry, a very bedraggled and exhausted bit of creation. It was interesting to watch the effect of this disaster upon every one in the office, including Mr. Finch himself.

Gentlemen and ladies vied with each other in showing attentive hospitality to the injured guest. He had his head rubbed and his wings lovingly stroked, and being too ill to resent these familiarities, he soon became accustomed to them. He was finally domiciled in a small basket and grew very chipper and tame indeed before his departure, which was after several days of such luxury and petting as would quite turn the head of anything less sensible than a finch.

It is said the gentleman who makes these birds his grateful pensioners buys ten pounds of seed at a time, and another gentleman and his wife, who reside at the Metropole, deal out their rations with so lavish a hand that their windows are fairly besieged with feathered beggars clamoring for food.

In a neighbor's yard I noticed always a small bare spot of ground. No matter how high the snow might drift around it, this small brown patch of earth lay dark and bare.

"Why do you keep that little corner swept?" I inquired.

"Oh, that is the birds' dining-room," was the answer, and then I noticed scraps of bread and meat and scattered crumbs and seeds. And as many times as I may look from my windows I always see from one to five fluffy bunches at work there stuffing vigorously.

Many of our teachers have made the lot of our common birds their daily study and delight. In the oldest kindergarten in the city the window sills are raised and the birds' food scattered upon a level with the glass, so that every action of the little creatures can be watched with ease by the children within.

In numbers of homes and in many of our business offices the daily needs of our little feathered brothers are thoughtfully cared for.

Let this feeling grow and this interest deepen in the hearts of Denverites, especially in the children's hearts. It will make this city a veritable paradise as the summer approaches, "full of the song of birds." It will make of it a heaven in the course of time, for not only the humble finch and snowbird, but for nature's most beautiful and aristocratic choristers.

"To-day is the day of salvation." To-day is the very best day of the best month in which to consider the needs of these poor which, thank God, "we have always with us." —Anne C. Steele, in Denver Evening Post, Feb. 3, 1899.

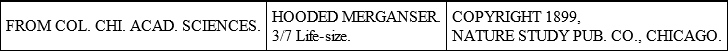

THE HOODED MERGANSER

(Lophodytes cucullatus.)LYNDS JONESEVEN the merest tyro in bird study need have no fear of confusing the male of this species with any other bird, as a glance at the picture will make evident. No other bird can boast such a crest, and few ducks a more striking pattern of dress or a more stately manner. The species inhabits the whole of North America, including Cuba, occasionally wandering to Europe and rarely to Greenland. It is locally common and even abundant, or used to be, in well watered and well wooded regions where fish are abundant, but seems to be growing less numerous with the advance of settlements in these regions. The food consists of fish, mollusks, snails, and fresh water insects which are obtained by diving as well as by gleaning.