полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 69, No. 427, May, 1851

It is not surprising that consequences so wide-spread and disastrous should follow the abandonment of the principle of protection to native industry; for it is the cement which alone has hitherto held together the vast and multifarious parts of the British empire. What was it, during the war, which retained all the colonies in steady and grateful loyalty to the British throne, and made even foreign colonial settlements hail with joy the pendants of our fleets fitted out for their subjugation, and in secret pray for the success of their enemy's arms? It was a sense of individual advantage – the consciousness that the Imperial Government on the throne knew no distinctions of locality, but distributed the same equal justice to the planter of Jamaica or the back-woodsman of Canada, as to the manufacturer of Manchester or the farmer of Yorkshire. All were anxious to gain admittance into the great and glorious empire, whose flaming sword, like that of the cherubim at the gate of Paradise, turned every way, and which extended to all its subjects, how distant and unrepresented soever, the same just and equal protection. Norway petitioned to be admitted into the great confederacy, and tendered its crown to Great Britain. Java mourned being shut out from it. The day when the British standard was withdrawn from the colonies, restored with imprudent generosity by victorious England at the peace of 1814, was to them one of universal mourning. There was no thought then of breaking off from the British empire; no mention of Bunker's Hill or Saratoga. The object of universal ambition was to gain admission, or remain in it.

And what were the dependencies which were then so anxious to obtain an entrance into, or retain their connection with, the British empire, and are now equally, or more solicitous, to break off from it? They were the West Indies, which at that period took off £3,500,000 worth annually of our manufactures, and employed 250,000 tons of our shipping; Canada, which has since, with 1,500,000 inhabitants, taken off above £3,000,000, and employed 1,100,000 tons of our shipping; and Australia, which now, with only 250,000 inhabitants, consumes above £2,000,000 worth of our manufactures; while Russia, with 66,000,000, takes off only £1,500,000 worth annually. So vast, various, and growing are the British colonies in every quarter of the globe, that half our export trade had become to us a home trade; and we enjoyed the inestimable advantage, hitherto unknown to any country that ever existed, of reaping domestic profits at each end of the chain which encircled the earth. This it was which held together the British empire, which preserved it intact amidst the greatest dangers, and caused the industry of the heart of the empire to grow with the growth, and strengthen with the strength, of its most distant extremities. In casting away our colonies, in destroying the bond of mutual interest which had so long held them in willing obedience to the heart of the empire, we have voluntarily abandoned our best customers; we have broken up the greatest and most growing dominion that ever yet existed upon earth; we have loaded ourselves at home with a multitude of useless mouths, which cannot find bread from the decline of the colonial market, and let the boundless fields of our distant provinces remain waste for want of the robust arms pining for employment at home, which might have converted them into an earthly paradise, and these islands into the smiling and prosperous heart of an empire which embraced half the globe.

The emigration which has gone on, and has now increased to 300,000 a-year, has done little to obviate these evils: for, since protection to our colonies has been withdrawn, four-fifths of it has gone to the United States, where the principle of protection to native industry is fully established, and constantly acted upon by their Government.

Matters, however, are not yet irremediable. Appearances are threatening, the danger is imminent, but the means of salvation are still within our grasp. All that is requisite is, to return with caution and moderation to the Protective policy which raised the British empire to such an unparalleled pitch of grandeur, and to abandon, cautiously and slowly, the selfish and suicidal policy which is now, by the confession of all, breaking it up. The great party – the National Party – which placed in Sir Robert Peel's hands the means of arresting this downward course, of restoring this glorious progress, still exists in undiminished numbers and increased spirit. It has gained one inestimable advantage – it has learned to know who are to be relied on as faithful to their principles, and who are to be for ever distrusted, as actuated only by the motives of ambition or selfishness. It has gained an equally important advantage in having had sophistry laid bare by experience. We have now learned, by actual results, at what to estimate the flattering predictions of the Free-Traders. The frightful spectacle of 300,000 emigrants annually driven for years together, since Free Trade began, into exile from the British islands; the proved decline of the taxable income of the industrious classes (Schedule D) by £8,000,000 since 1842, and £6,000,000 since 1846; the rise of our importation of foreign grain, in four years, from less than 2,000,000 of quarters annually to above 10,000,000; the increase of our imports in the last eight years by sixty-eight per cent, while our exports have only increased by fifty-one per cent during the same period; the increase of crime in a year of boasted prosperity to 74,000 commitments, a greater amount than it had ever reached in one of the severest adversity; the diminution of Irish agricultural produce by £8,000,000 in four years, and of British by at least £60,000,000 in value during the same period; the total ruin of the West Indies, the approaching severance of the other colonies from our empire, or their voluntary abandonment by our Government; the admitted increase of the national debt by £20,000,000 during twenty years of general peace; – these, and a hundred other facts of a similar description, have opened the eyes of so large a proportion of the nation to the real tendency of the new system, that it has already become evident, even to their own adherents, that, at latest, at the next election, if not before, the Protectionists will be in power.

Lord Stanley has announced, with the candour and straightforwardness which become a lofty character, what are the principles on which he is prepared to accept office. He was instantly to have taken off the Income Tax, which presses so severely on the industrious classes, and supplied the deficiency, which would amount to about £3,000,000, by a moderate import duty on all foreign commodities. The effect of these measures would have been incalculable: it is hard to say whether they would have benefitted the nation most by the burdens which were taken off, or those which were laid on. The first would relieve the most hard-working and important part of the middle class, and let loose above £5,000,000 a-year, now absorbed by the Income Tax, in the encouragement of domestic industry; the second would produce the still more important effect of enabling the nation to bear the burden of the necessary taxation, and compel the foreigners, who now so liberally furnish us with everything we desire tax-free, to bear the same proportion of our burdens which we do of theirs. A large part of the taxes of Prussia, and all the Continental States – the whole of the American – is derived from import duties; and in this way our artisans and manufacturers are compelled to pay a considerable proportion, probably not less than a half, of the national burdens of these states. Meanwhile their rude produce is admitted duty free to our harbours, so that we get no part of our revenue from them. They levy thirty per cent on our goods, and the whole of that goes to swell their revenue, to the relief of their subjects; we levy two or three per cent on their grain, and the miserable pittance is scarcely perceptible amidst the immense load of our taxation.

The benefit of the fiscal changes which Lord Stanley proposed would have been great, immediate, and felt by the most meritorious and heavily burdened class of the community – the middle class; the burden for which it would have been commuted would have afforded a certain amount of protection to native industry, so as to relieve the most suffering classes engaged in production, and that at the cost of a burden on consumers so trifling as to have been altogether imperceptible.

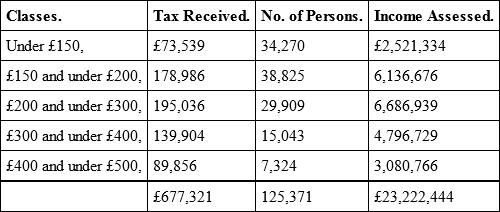

To illustrate the extreme injustice of the Income Tax, and the way in which it presses on the most industrious and hard-worked, as well as important class of the community, we subjoin a Table of Schedule D (Trades and Professions) for the year ending 5th April 1848; and we take that year in preference to the subsequent ones, to avoid the objection of the commercial crisis of 1848 having rendered the view partial and deceptive.61 From this important Table it appears that the sums received from persons under £500 a-year were —

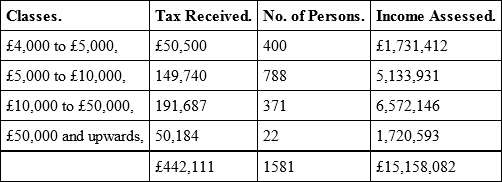

And the incomes above £4000 stood thus: —

Note.– From a Return ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 31st May 1849.

So that out of £1,685,977, which was the sum received from persons in trades and professions in Great Britain that year, no less than £677,000 came from 125,371 persons whose incomes were under £500 a-year, while only one thousand five hundred and eighty-one persons were assessed as having incomes above £4000! This dreadful tax therefore is, par excellence, the shopkeeper's, manufacturer's, and professional man's tax; and they are assessed for it in numbers sixty times more numerous than the rich. And yet the assessment of all is laid on at the same rate! Is it surprising that the Chancellor of the Exchequer said, in support of this tax, that it was so unjust to all, that no one was worse off than his neighbour, or had any reason to complain? And let every tradesman, manufacturer, clerk, and professional man, who pays this odious and unjust tax for the next three years, recollect that he owes the burden entirely to the Free-Traders; for if they had not been in a majority in the House of Commons, Lord Stanley would have come in and taken it off.

Two statesmen, belonging to different schools, have come prominently forward during the late Ministerial crisis; and to one or other of them, or perhaps to both alternately, if they live, the destinies of the empire, for a long period of time, will in all probability be intrusted. These are Lord Stanley and Sir James Graham. Both are men of great ability, vast application, extensive experience, tried business habits, great oratorical and debating power; but, in other respects, their characters are as opposite as the poles are asunder. As usual, in such cases, while their characters bear the marks of distinct individuality, they are the types or representatives of the two great parties which now divide the British empire. The first is straightforward, intrepid, and manly – patriotic, but not vacillating – willing to undertake the burdens of office, but unwilling to do so unless he can carry out the principles which he deems essential to the salvation of his country. The second is ambitious, cautious, diplomatic, desirous of power, but fearful of the shoals with which it is beset; and desirous so to shape his policy and conceal his intentions, as to avoid shipwreck by coming openly into collision with any powerful party in the state. The device of the one is the steady polar star of duty; the guide of the other the flickering light of expedience. The first refused the Premiership when offered to him by his sovereign, because he thought the time had not yet arrived when he could carry out his principles; the latter has so often changed his side, and held office under so many parties, that no man alive can tell what his principles are. The first broke off from Sir Robert Peel in office, when he deserted his principles; the latter deserted his principles to join Sir Robert Peel when entering on power. The first, while still in opposition, has already announced to the country what line of policy he is determined to adopt if placed in power; the last has talked of a mutiny in the army as a reason for continuing the ruin of agriculture, and a rebellion in Ireland as a reason for tamely submitting to Papal aggression. The one is of the true breed of the British lion, the other a mongrel cross between the Whig and the Free-Trader.

1

Longfellow's Poetical Works.

Bryant's Poetical Works.

Whittier's Poetical Works.

Poems. By James Russell Lowell.

Poems. By O. W. Holmes

2

"What was the star I know not, but certainly some star it was that attuned me unto thee."

3

Lettres sur l'Amérique. Par X. Marmier. 2 volumes. Paris, 1851.

The United States and Cuba. By John Glanville Taylor. London, 1851.

4

La Havane. Par Madame la Comtesse Merlin.

5

Thick clumsy buckskin gloves.

6

Amongst these, Professor James Johnston now takes honourable rank. His valuable Notes on North America reached us too late for notice in the present article – admitting even that they could with propriety have been included in a review of works of a lighter and more ephemeral character. His volumes, which address themselves particularly to the agriculturist and emigrant, are replete with useful information, and we shall take an early opportunity of drawing attention to their instructive and interesting contents.

7

A species of gigantic reed or cane, which attains an elevation of fifty feet, in clumps of two or three hundred stems.

8

The Book of the Farm. By Henry Stephens, F.R.S.E. Second Edition. 2 vols. 8vo. Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London: 1851.

9

Those acquainted with the writings of Tull, Arthur Young, Marshall, and Elkington, must know that, although not exempt from errors, they evolved the leading principles of a right agriculture. Indeed, we would seem almost to be recovering only the lost principles and practices of the Roman farmers of old. They seem to have known the mode of manuring ground by penning sheep upon it – nay, what will astonish Mr Mechi, they practised the plan of feeding them in warm and sheltered places with sloping and carefully prepared floors, upon barley and leguminous seeds, hay, bran, and salt. They knew the advantage of a complete pulverisation of the soil, and the necessity of deep ploughing. Their drainage was deep, and if Palladius does not mislead us, they seem in certain cases to have employed earthenware or tile-drains. But to those who wish to know more of Roman husbandry, and who may not have leisure or opportunity to consult the originals, we have great pleasure in recommending Professor Ramsay's (of Glasgow) paper entitled "Agricultura," in the last edition of Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, – an admirable specimen of condensed erudition.

10

Modern State Trials: Revised and Illustrated, with Essays and Notes. By William C. Townsend, Esq., M.A., Q.C., Recorder of Macclesfield. In 2 vols. 8vo. Longman Co., 1850.

11

The duty here performed by the President of the Court is in England discharged by an officer of the Court called the Clerk of Arraigns.

12

This was subsequently altered to "claiming to be Earl of Stirling." – Swinton, p. 48.

13

Ante, p. 477 et seq.

14

Bell's Dictionary of the Law of Scotland, p. 844. In civil cases this rule is reversed. —Id. ib.

15

Alison's Practice of the Criminal Law of Scotland, p. 651.

16

Swinton, p. 196.

17

Ante, p. 470, et passim.

18

Ante, p. 474.

19

Swinton, p.309.

20

Per Lord Meadowbank, Id. ib.

21

Id., p. 84.

22

Id., p. 94.

23

Ante, p. 473.

24

Swinton, p. 205.

25

Ante.

26

Id., p. 475. Swinton, App., p. vii.

27

Ante, p. 484.

28

Swinton, p. 311. This seems a slight inaccuracy, on the part of the learned Judge, of fifty-eight instead of fifty. —Ante, p. 484.

29

Pref. p. xxi.

30

Swinton, p. 209.

31

When the precept issues in favour of a Writer to the Signet, or of the Keeper of the Signet, (as Lord Stirling then was,) the precept passes the signet gratis: and that word is written at the bottom. – Swinton, p. 84.

32

Ante, p. 470.

33

Ante, p. 483.

34

Starkie On Evidence, vol. i. p. 8, note G. 3d ed.

35

See the Pedigree, ante, p. 473.

36

Swinton, Append., p. xxiii.

37

Id., p. xxix.

38

Ante, p. 484-7.

39

See it in extenso, ante, p. 486.

40

Ante, p. 475.

41

Swinton, pp. 143-4.

42

Id., App. lviii.

43

Swinton, p. 237.

44

Ante, pp. 466, 480.

45

Ante, p. 480.

46

Ante, p. 467.

47

Ante, pp. 481-2.

48

Swinton, p. 263.

49

Swinton, p. 263.

50

Ib. p. 265.

51

This superscription was charged in the indictment as a forgery.

52

Ib. p. 293-4.

53

Swinton, p. 324.

54

Swinton, p. 333-4.

55

Such a thing would not be allowed in England, except, probably, under very special circumstances. We never witnessed anything of the kind.

56

Swinton, pp. 333-4.

57

Ib., pp. 335-6.

58

In Scotland, the verdict in a criminal case is according to a majority of the jury; in a civil case they must be unanimous.

59

This was the anonymous letter to Madlle. le Normand, dated the 10th July 1837, accompanying the map professed to have been left with her so mysteriously on the ensuing day. See it in extenso in our last Number, p. 482.

60

Swinton, p. 300.

61

Table showing Number of Persons charged for the Income Tax, and Sum received, for the Year ending 5th April 1848 (under Schedule D.)