полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 70, No. 434, December, 1851

The question naturally occurs – How is it that, with all these natural advantages and encouragements to colonisation, and with its proximity to our shores, so very small a proportion – not more than one in sixty or seventy of the emigrants from Great Britain – make New Brunswick their destination? Professor Johnston, while he maintains that, taking population into account, New Brunswick is in this respect no worse off than Canada, adverts to several causes of a special nature which may have retarded its settlement. But the truth is, that the question above started leads us directly to another of far greater compass and importance – What is the reason that all our colonies taken together absorb so small a proportion of our emigrants compared with the United States? What is the nature of the inducements that annually impel so large a number of our countrymen to forfeit the character of British subjects, and prefer a domicile among those who are aliens in laws, interests, and system of government?

We hardly know how to venture upon anything connected with the ominous subject of emigration, at a moment when the crowds leaving our shores, at the rate of nearly a thousand every day, are such as to startle the most apathetic observer, and shake the faith of the most dogmatic economist in the truth of his speculations. This is not the place to inquire what strangely compulsive cause it may be that has all at once swelled the ordinary stream of emigration into a headlong torrent.6 Mayhap it is neither distant, nor doubtful, nor unforetold. But whatever it may be, there stands the fact – which we can neither undo, nor, for aught that can be seen at present, prevent its annual recurrence in future, or say how and when the waves are to be stayed. "When the Exe runs up the streets of Tiverton," says a certain noble prophet – whose vaticinations, however, have not been very felicitous hitherto – "then, and not till then, may we expect to see the reversal of the free-import system;" and then, and not till then, we take leave to add, may we hope to see the ebbing of that tide of British capital and British strength which is now flowing strongly and steadily into the bay of New York.

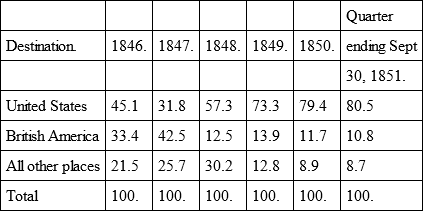

Proportion of British Emigration to the Colonies and to the United States, 1846-50 inclusive.

The accompanying abstract, from the returns of the Emigration Commissioners, exhibits two most remarkable results: – 1st, The proportion of emigration to British America and other destinations is gradually falling off; 2d, That to the United States is steadily and rapidly increasing, so that they now receive four out of every five emigrants who leave our shores. Is this distribution to be regarded as a matter of indifference in a political point of view? Are we to understand that it is no concern to us who remain behind, whether the labour and capital of those who leave us shall go to fill up the vacuum of our own colonial empire, or to carry new accessions of wealth and power to those in whose prosperity (to put the matter mildly) we have only a secondary interest? This question the consistent Free-Trader is bound to answer unhesitatingly in the affirmative. In his cosmopolitan philosophy, the interests of one country are no more to be considered than those of any other. The theory of absolute freedom of exchange expunges altogether the idea of nationalism, and regards man, not as a member of this or that community, but as the denizen of a great universal republic. Local and historical associations – ties of kindred and of birth – are only so many obstructions in the way of human progress; and an Englishman is nothing more than the subject of certain animal wants and instincts, the gratification of which he must be left to seek wherever he finds the materials most abundant. Such is Free Trade in its true scope and ultimate tendency. What shall be said, then, of the consistency or sincerity of those pseudo-apostles of the doctrine, who, having been the most active in promoting that nibbling and piecemeal legislation which they choose to call freedom of trade – who have been loudest in proclaiming a universal commercial fraternity, and in denouncing colonies as a wasteful encumbrance – are now the first to take alarm at the natural and inevitable result of their own measures, and to call out for a better regulation of emigration; in other words, for legislative interference with the free action of those of our countrymen who, being thrust out of employment in the land of their birth, are so literally following out the great maxim of buying in the cheapest market and selling in the dearest?

The text is a tempting one, but we must refrain from wandering further from the subject with which we started – namely, the inducements which lead so many of our emigrants to select the United States as their future home. One of the prevalent causes has been very well stated by Professor Johnston – that which we may call the capillary attraction of former emigration: —

"A letter from a connection or acquaintance determines the choice of a place to go to, and, without further inquiry, the emigrant starts. Thus for a while, emigration to a given point, once begun, goes on progressively by a sort of innate force. Those who go before urge those who follow by hasty and inaccurate representations; so that, the more numerous the settlers from a particular district, the more numerous also the invitations for others to follow, till the fever of emigration subsides. In other words, in proportion as the home-born settlers in one of these countries increases, will the number of home-born emigrants to that country increase —but for a time only, if the place have real disadvantages." – (Vol. ii, p. 204.)

It is vain to shut our eyes to the fact that the government of the United States offers to the emigrant many real, substantial, and peculiar advantages. The first and most important aid that can be given to the intending settler is a complete and accurate survey of the country; and this has been accomplished by the States government at great expense, but in so perfect a manner that a purchaser has no difficulty in at once pointing out, on the official plan, any lot he may have selected in the most remote corner of the wilderness. The next point of importance to him is simplicity of conveyance and security of title; and so effectual and satisfactory is the American system that litigation in original land-titles is almost unknown. Then as to the weighty consideration of price – which perhaps ought to have been first mentioned – the uniform and very low rate in the States of 5s. 3d. an acre saves infinite trouble, disputation, and jealousy. Such are some of the temptations held out to the intending purchaser of land; and it must be confessed that, in each particular, they present a striking contrast to the difficulties he has to meet in some of the British colonies – the arbitrary changes of system, the vexatious delays, and the comparatively exorbitant charges – which must appear to the settler as if they had been contrived on purpose to discourage him. When we add to these the prospects of ready employment in the States held out to other classes of emigrants, and the stringent laws lately made for their protection, both on the passage and on their arrival, we cannot be at a loss to see that the direction which emigration has lately taken is not the result of chance or caprice, but of a deliberate comparison of advantages, which the most ignorant can easily understand and appreciate.

The main object of Professor Johnston's visit being of a scientific character, his remarks on the general topics of manners and politics occur only incidentally; but it is impossible for any traveller to keep clear of such subjects in writing of a country, the peculiarities of which are pressed upon his notice at every hour of the day, and at every corner of the street. Rabelais tells us of a certain island, explored by the mighty Pantagruel, whose inhabitants lived wholly upon wind– that is, being interpreted, on flattery; and the visitor of the States who finds himself, as it were, pinned to the wall, and compelled to yield up his admiration at discretion, may be sometimes tempted to believe that he has made a similar discovery, and that the flatulent diet of compliment is somehow congenial to an American appetite. Professor Johnston seems to have had his candour or his eulogistic powers sometimes severely tested, if we may guess from his quiet hint, that "it is unpleasant to a stranger to be always called on to admire and praise what he sees in a foreign country; and it is a part of the perversity of human nature to withhold, upon urgent request, what, if unasked, would have been freely and spontaneously given." He is of course prepared for the reception which any work, aiming at mere impartiality, is sure to meet with among Transatlantic critics; and it will, therefore, not surprise him to find that the above peccant sentence has been already pounced upon by them as proving malice prepense, and as affording a significant key to all his observations on the institutions of the States.

The following extract explains the origin of two of those euphonious party designations in which our neighbours delight, and which may perchance have puzzled some of our readers: —

"In England, to be a democrat still implies a position at the very front of the movement party, and a desire to hasten forward political changes, irrespective of season or expediency. But among the American democrats there is a Conservative and a Radical party. The former, who desire to restrain 'the amazing violence of the popular spirit,' are nicknamed by their democratic adversaries the 'Old Hunkers;' the latter, who profess to have in their hearts 'sworn eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man,' are stigmatised as 'Barnburners.' The New York Tribune, in reference to the origin of the names themselves, says that the name 'Hunkers' was intended to indicate that those on whom it was conferred had an appetite for a large 'hunk' of the spoils; though we never could discover that they were peculiar in that. On the other hand, the 'Barnburners' were so named in allusion to the story of an old Dutchman who relieved himself of rats by burning his barns, which they infested, just like exterminating all banks and corporations, to root out the abuses connected therewith." – (Vol. i. p. 218.)

Equally mysterious is the term "log-rolling," though the thing itself is not altogether unknown in legislatures nearer home.

"When the trees are felled and trimmed, rolling the logs to the rivers or streams down which they are to be floated, as soon as the spring freshets set in, remains to be done. This being the hardest work of all, the men of several camps will unite, giving their conjoined strength to the first party on Monday, to the second on Tuesday, and so on. A like system in parliamentary matters is called 'log-rolling.' You and your friends help me in my railroad bill, and I and my friends help you with your bank charter; or sometimes the Whigs and Democrats, when nearly balanced, will get up a party log-rolling, agreeing that the one shall be allowed to carry through a certain measure without much opposition, provided a similar concession is granted to the other." – (Vol. ii. p. 297.)

The Notes convey to us the strong impression that Professor Johnston's visit to the West has operated as a wholesome corrective of a certain tendency in his political opinions. He seems to have left home with a warm admiration of American institutions generally, which, like Slender's love, "it pleased heaven to diminish on further acquaintance." At all events, he could not avoid being struck with some of the many perplexities and anomalies that result from referring everything directly to the popular voice. In England, whatever dissensions may arise about the enactment of law, all are agreed in a sensitive jealousy as to the purity of its administration. The most rampant Radical among us looks upon justice as far too sacred a thing to be hazarded in the rude chance-medley of popular election. The keenest partisan feels that, in the lofty and unswerving integrity of our judges, he possesses a substantial security and blessing, for the loss of which no place, power, or parliamentary triumph, could compensate. To one accustomed to regard with veneration the dignified independence of the judicial office in Great Britain, nothing will appear more harshly repugnant to sound policy than the system, lately introduced into some of the New England States, of appointing all judges, high and low, by the votes of the electors of the district over which they are to preside, and for a limited term of years.

"It was deservedly considered a great triumph when the appointment of judges for life liberated the English bench from the influence of the Crown, and when public opinion became strong enough to enforce the selection of the most learned in the law for the highest judicial offices. Now, passing over the objection which some will strongly urge, that the popular electors are not the best judges of the qualifications of those who aspire to the bench, and that the most popular legal demagogue may expect to obtain from them the highest legal appointment, it may be reasonably asked whether popular influence in seasons of excitement, and on questions of great moment, may not bias the minds of judges whose appointment is in the hands of the people? – whether the fear of a coming election may not deter them from unpopular decisions? The influence of a popular majority may here as profoundly pollute the fountains of justice as the influence of the Crown ever did among us at home." – (Vol. i. p. 150.)

At first sight, it seems quite unaccountable that an enlightened people should ever have devised or sanctioned a system which so obviously exposes the bench to the risk of corruption; and one is at a loss to reconcile a reverence for the law with an ordinance that subjects her minister to the ordeal of canvassing and cajoling all and sundry – perhaps the very men who may next day be in the dock before him. But the root of the anomaly is not hard to find. Into the purest of republics ambition and cupidity – the love of office and the love of dollars – will force their way. But then, under that form of constition, situations of trust and emolument are necessarily few in comparison to the number of candidates for them. The offices in the civil departments of the United States governments are not numerous. The navy employs altogether some five hundred officers above the rank of midshipman – exactly the number of our post-captains; and the whole army of the Confederation, rank and file, musicians and artificers included, is very little over ten thousand men. There is little temptation to enter the medical profession, in which learning and experience go for nothing, and a Brodie is precisely on a level with a "Doctor Bokanky;" – nor the Church, in which the pastor is hired by the twelvemonth, and is thought handsomely paid with a wage of £100 a-year. What field, then, remains for the aspiring spirit but the law? – and what wonder if the sixteen thousand attorneys, who, we are told, find a living in the States, and take a leading part in the management of all public business, should vote "the higher honours of the profession" far too few to be retained as perpetual incumbencies? Hence has sprung the device of popular election to, and rotation in, the sweets of office, which, by "passing it round," and giving everyone a chance, is designed to render it as generally available as possible. The constitution of the judiciary is not uniform, but varies in almost every different state. In New York, the Judges of Appeals, as well as those of the Supreme and Circuit Courts, are elected by the people at large, and for a term of eight years, each leaving office in rotation. In New Jersey they are appointed for six years by the governor and senate; in Vermont, annually by the legislature. In Connecticut nearly the same system prevails as that in Vermont; while in Massachusetts the judges retain office "during good behaviour." The salaries are not less various, in some States the remuneration of judges of supreme courts being £500 a-year, which is about the highest rate; and in others so low as £180. There are no retiring allowances in any case; and as they are thus liable to be thrown out of office at an uncertain period, or compelled to vacate it after a short term of years, it can scarcely be expected that such remuneration will secure the highest grade of legal acquirements, either for the bench itself, or for the inferior offices of attorney-generalships and chief-clerkships, which are all held by the same lax tenure of popular favour. Even if the system has "worked well," as it is said to have done by American writers, during the four or five years it has been in operation in New York – even if it be true that the lawyers of the Empire State have, by avoiding the snares thrown in their way, given proof individually of the probity of Cato, and of a constancy worthy of Socrates, we still say that the State does wrong in putting their virtues to such a test. Mr Johnston supplies us with an example of the temptation it holds out to a dangerous pliancy of principle. Most of our readers must be aware of the existence of an active and noisy party in the States, who, under the name of "Anti-renters," are seeking to free themselves from payment of certain reserved rents, or feu-duties, as they would be termed in Scotland, which form the stipulated condition of land tenure in a certain district.

"The question has caused much excitement and considerable disturbance in the State. It has been agitated in the legislature and in the courts of law, and the supposed opinion in regard to it of candidates for legal appointments, is said to have formed an element which weighed with many in determining which candidate they would support. During the last canvass for the office of attorney-general, I met with the following advertisement in the public journals of the State: —

"'I have repeatedly been applied to by individuals to know my opinions with regard to the manorial titles, and what course I intend to pursue, if elected, in relation to suits commenced, and to be commenced, under the joint resolution of the Senate and Assembly. I have uniformly replied to these inquiries, that I regard the manor titles as a public curse which ought not to exist in a free government, and that if they can be broken up and invalidated by law, it will give me great pleasure; and I shall prosecute the pending suits with as much vigour and industry as I possess, and will commence others, if, on examination, I shall be satisfied there is the least chance of success. I regard these prosecutions as a matter of public duty, and, in this instance, duty squares with my inclination and wishes.

'L. S. CHATFIELD.'"Mr Chatfield," adds Professor Johnston, "is now attorney-general; and I was informed that the known opinions of certain of the old judges on this exciting question was one of the understood reasons why they were not re-elected by popular suffrage, when, according to the new constitution, their term of office had expired." – (Vol. ii. p. 291.)

Here, then, we see the highest law officer of the State openly "bidding" for office – truckling to faction – and indecently condescending to enact the part of a "soft-sawderer." That term, we presume, is the proper American equivalent for the stinging soubriquet with which Persius stigmatises some Chatfield – some supple attorney-general of his day —

"Palpo, quem ducit hiantemCretata ambitio."When persons of the highest official position scruple not thus undisguisedly to trim their course according to the "popularis aura," one can scarcely help suspecting a want of firmness of principle and genuine independence among the classes below them. De Tocqueville's observations have taught us to doubt whether the tree of liberty that grows under the shadow of a tyrant majority can ever attain a healthy stability, however vigorous it may appear externally. No one questions that the Americans enjoy, under their institutions, very many of the blessings of a liberal and cheaply-administered government. You have perfect liberty of speech and action, so far as the government is concerned. The avowal of one's opinion is not followed, as in Italy, or in the rival republic of France, by a hint that your passport is ready, or by the polite attendance on you, wherever you go, of a mysterious gentleman in black; but you feel yourself, nevertheless, perpetually "en surveillance," and constrained either to sail with the stream, or to adopt a reserve and reticence which, to an Englishman, is almost as irksome as the knowledge that there is a spy sitting at the same dinner-table with him.

The spirit of Professor Johnston's strictures on such anomalies will, of course, insure his being set down by his democratic friends in America as an unmitigated "old hunker;" and he certainly shows no great liking for practical republicanism. But to find fault with our neighbours' arrangements, and to be contented with our own, are two very different things; and, accordingly, our author takes many opportunities, as he goes along, of showing that he is quite aware of the innumerable rents in our own old battered tea-kettle of a constitution, and of the infinite tinkering it will take to make it hold water.

We should have held him unworthy of the character of a true Briton if he had omitted the occasion of a grumble at our system of taxation, though, of course, we differ with him entirely in the view he takes of the evil. After an elaborate comparison of the taxation in the United States with that of Great Britain, he sums up all with the following somewhat sententious apophthegm: —

"The great contrast between the two sections of the Anglo-Saxon race on the opposite sides of the Atlantic is this —On the one side the masses rule and property pays; on the other side property rules and the masses pay." – (Vol. ii. 254.)

The sentence sounds remarkably terse and epigrammatic. Most of such brilliant and highly-condensed crystals of wisdom, however, will be found on analysis to contain, along with some exaggerated truth, a considerable residuum of nonsense; and this specimen before us, we apprehend, forms no exception. Even if the fact so broadly asserted were indisputable, we should still be inclined to doubt, after what the author has himself told us, whether the "rule of the masses" is always an unmixed blessing to a community. He has seen enough of it to know at least that the preponderance of popular sway is not incompatible with much social restraint – with prejudice and narrow-mindedness – with what he considers a false commercial principle – with a disregard of public faith, and of the rights of other nations; and lastly, with a contempt of the rights of humanity itself, and a legalised traffic in our fellow men. But, if we understand him rightly, he does not so much defend the abstract excellence of the democratic principle as advocate a nearer approach, on our part, to the American model of taxation. In the States, he says, property pays – in England the masses pay; – that is, if we strip the proposition of its antithetical obscurity, the owners of property pay less here than they do in America – not only absolutely less, but less in proportion to the whole amount of taxation. The calculations on which he founds this assertion are too long and involved to be quoted at length, but we will endeavour to abridge them so as to enable the reader to judge of their accuracy.

The taxes in the United States are of three classes: 1st, – the national taxes, amounting to about six millions a-year, which are raised chiefly by customs duties on imports; 2d, – the state taxes; 3d, – the local taxes, for the service of the several counties, cities, and townships. These two last classes are levied chiefly in the form of an equal rate assessed upon the estimated value of all property, real and personal.

In order to compare the incidence of the public burdens upon property in the two countries, Professor Johnston selects the case of New York State, in which the total taxable property (personal as well as real) in 1849 was 666,000,000 of dollars, and the amount of rates levied for state and local taxes 5,500,000 dollars, or about 4⁄5 per cent on the gross valuation. Turning then to Great Britain, (excluding Ireland,) he sets down the fee simple value of the real property alone in estates above £150 a-year, as rated to the income-tax, at £2,382,000,000.