полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 68, No 422, December 1850

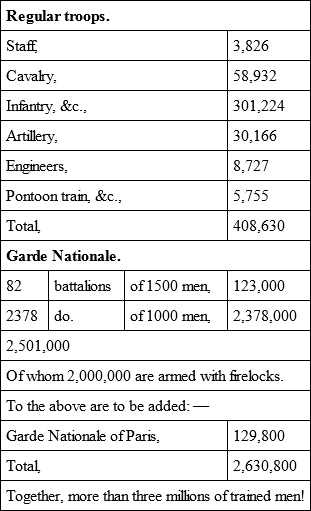

We regret to observe that, since then, the Times seems to have changed its tone on this very important subject, and it now regards the preparation necessary to insure the security of England as too costly for the object proposed. This is a novel view, even in ethics. We have been taught that it was our duty, in case of necessity, to expose even our lives in defence of our country; and we do hope that there are some among us who still adhere to that noble lesson. No such sacrifice is required just now. All that is demanded – and demanded it ought to be, not by isolated writers, or even high and competent authorities, but by the general voice of the nation – is, that our navy should be put upon an efficient footing – that the Admiralty should be reformed, and no chief of it appointed who is not conversant with the details of the service of which he is selected as the head – that no other Minto should be allowed to make his high maritime office the source of family patronage – that a ready and constant supply of skilled and experienced seamen should be secured – and that the vast expenditure lavished on our ships should not be rendered nugatory for want of hands to man them adequately when launched. Furthermore, we require that the standing force of our army at home should be so augmented as to render it certain that, in any sudden emergency, we may not have to depend upon the voluntary efforts of a panic-stricken and undisciplined mob. We have already spoken of the chances of our being involved in war, and also of the possibility of an invasion: let us now examine what amount of disposable forces we have ready, in the event of such a terrible emergency. Our muster-roll, inferior certainly to the Homeric catalogue, is as follows: – In Great Britain and Ireland we have precisely 61,848 regular enlisted soldiers of all departments of the service! Of these, 24,000 are stationed in Ireland alone, whence, in the event of the occurrence of any disturbance, they could scarcely be withdrawn; so that the whole defensible force of England and of Scotland is reduced to rather less than 38,000 soldiers! That number would hardly be doubled were we to add the whole of the pensioners, more or less worn out, the corps of yeomanry, and the half-drilled workmen of the dockyards: and with this force some of us are content to await invasion; whilst others, more reckless still, are even clamouring for its reduction! Farther, as if we were resolved to push on folly to the furthest extreme, the drawing of the militia has been, by Act of Parliament, suspended; so that even that slender thread, which in some degree connected the civilian with the military service, has been broken. This is the bare naked truth, with which foreigners are perfectly well acquainted, and which they will continue to bear in mind, notwithstanding our attempts to amuse them, with glass-houses and gigantic toy-shops.

What would not the elder Buonaparte have given to find us in such a state! Very far, indeed, are we from imagining that the present President of the French Republic bears any personal ill-will to this country, wherein he has met with much hospitality; but, giving him the utmost credit for amicable dispositions and pacific intentions, we cannot forget the peculiarity of the position which he occupies, or the varied influences which control him. However we may wish to believe the contrary, it is certain that France regards herself rather as the rival than as the ally of England. It cannot, indeed, be otherwise. France has recollections, not of the most soothing kind, which no lapse of time has been able to efface; and these will infallibly, when an opportunity occurs, regulate her future conduct.

And how stands France at this moment with regard to military preparation? Observe – there is no enemy threatening her from without. Of all states in Europe she is the least likely to be attacked. Yet we find her available force as follows: —

We need not dwell on the disproportion which is apparent here; indeed, our whole task is one from which we would most willingly have been held excused. It is not pleasant either to note or to reiterate the undoubted fact of our weakness; and yet what help is there, when purblind demagogues are allowed by senseless clamour to drown the accents of a voice still speaking to us from the verge of the grave? Let Sir Francis Head illustrate this point, and may his words sink deep in the heart of an unwise generation.

"Why, we ask, have the Duke of Wellington's repeated prayers, supplications, admonitions, and warnings "to various Administrations," and through the press to the British people, been so utterly disregarded? Without offering one word of adulation – we have personally no reason to do so – we cannot but observe, that no problem in science, no theory, important or unimportant, has ever been more, thoroughly investigated than the character of the Duke of Wellington by his fellow-countrymen.

"During the spring and summer of his life, the attention of the British nation followed consecutively each movement of his career in India, Portugal, Spain, Denmark, the Low Countries, France, and latterly in the senate. In the autumn of his life, the secret springs which had caused his principal military movements, as well as his diplomatic arrangements, were unveiled by the publication of despatches, letters, and notes, official as well as private, which without palliation or comment developed the reasons, – naked as they were born, – upon which he had acted, on the spur of the moment, in the various predicaments in which he had been placed. In the winter of his life, bent by age, but with faculties matured rather than impaired by time, it has been his well-known practice, almost at the striking of the clock, to appear in his place in the House of Lords, ready not only to give any reasonable explanations that might be required of him, but to disclose his opinions and divulge his counsel on subjects of the highest importance. Every word he has uttered in public has been recorded; many of his private observations have been repeated; his answers to applications of every sort have usually appeared in print; even his "F.M." epigrammatic notes to tradesmen and others, almost as rapidly as they were written, have not only been published, but in one or two instances have actually been sold by auction. Wherever he walks, rides, or travels, he is observed; in short, there never has existed in any country a public servant whose conduct throughout his whole life has been more scrupulously watched, or whose sayings and doings have by himself been more guilelessly submitted to investigation. The result has been that monuments and inscriptions in various parts of London, of the United Kingdom, and throughout our colonial empire, testify the opinion entertained in his favour; and yet although in the Royal Palace, in both Houses of Parliament, at public meetings, and in private society, every opportunity seems to be taken to express unbounded confidence in his military judgment, sagacity, experience, integrity and simplicity of character, yet in our Legislature, in the Queen's Government, as well as throughout the country, there has for many years existed, and there still exists, an anomaly which foreigners observe with utter astonishment, and which history will not fail to record – viz., that his opinion of the defenceless state of Great Britain has, by statesmen, and by a nation who almost pride themselves on their total ignorance of the requirements of war, been utterly disregarded!"

We have but little space left for further comment. We do not consider it necessary to follow Sir Francis Head through almost any portion of his masterly details, or to sketch, even in outline, the picture which he has drawn of the possible consequences of our supineness. On these points the book must speak for itself. We venture to think that it will not be without some effect, however it may be assailed by vulgar abuse, or depreciated by contemptible flippancy. It speaks home to the feelings of Englishmen, has the merit of great perspicuity, and deals prominently with facts which can neither be gainsaid nor denied.

Even to the apostles of peace – the fanatics, as we think, of the present age – Sir Francis holds out the olive branch. He represents to them, what they probably cannot see, that the only method of realising their cherished idea of voluntary arbitration and reduction of armaments, is by maintaining at a crisis like the present the true balance of power. And certainly he is right, if there be anything at all in their scheme. For our own part, we hold it to be absolutely and entirely chimerical. It is a mere phase or fiction of that wretched notion of cosmopolitanism, which some years ago was preached by Cobden – a notion to which the events and experiences of each successive month have given the practical lie, and which never could have been hatched except in the addled brain of some ignorant and vainglorious egotist. By herself, Britain must stand or fall. The good and the evil she has done – the influence which she has exerted, one way or the other, over the destinies of the human race, is written in the everlasting chronicle; and her fate is in the hand of Him who raises or crushes empires. What trials we may have to undergo – what calamities to suffer – what moral triumphs to achieve – are known to Omnipotence alone. But as a high rank in the scale of nations has been given us, let us, at all events, be true to ourselves, in so far as human prudence and manly foresight can avail. Let us not, for the sake of miserable mammon – or, still worse, for the crude theories of a pragmatical upstart – imperil the large liberties which have been left to us, as the best legacy of our forefathers. Our duty is to uphold, by all the means in our power, the honour and the integrity of our native land: nor dare we hope for the blessing or the countenance of the all-controlling Power, one moment after we have proved ourselves false to the country which gave us birth.

THE POPISH PARTITION OF ENGLAND

If a religious Revolution consists in a powerful change in the religious feelings of a country, then are we at this moment in the midst of a religious Revolution! If a spirit of ardour suddenly starting forth in a period of apathy, if public zeal superseding public indifference, and if popular fidelity to a great forgotten cause, pledging itself to make that cause national once more, exhibit an approach to a miracle, then there has been made on the mind of England an impression not born of man. But if those high interpositions have always had a purpose worthy of the source from which they descend, we must regard the present change of the general mind as only a precaution against some mighty peril of England, or a preparation for some comprehensive and continued triumph of principle in Europe. That England is a tolerant country has never been questioned. Though the whole frame of its constitution is actually founded on the supremacy of the sovereign, and, of course, on the derivation of ecclesiastical power, as well as of every other, from the throne; though therefore the high appointments of the Church have been vested in the Crown, and the subordination of the great body of the clergy has necessarily connected them with the throne, the principle of toleration shapes all things. The ecclesiastical constitution excludes all violence to other disciplines; allows every division of religious opinion to take its own way; and even suffers Popery, with all its hostility, to take its own way – to have its churches and chapels, its public services, its discipline, and all the formalities, however alien and obnoxious, which it deems important to its existence.

None familiar with the history of Popery can doubt that its principle is directly the reverse – that it tolerates no other religion; that it suffers no other religious constitution; that where the tree of Popery lifts its trunk and spreads its branches, all freedom of opinion withers within its shade.

Rome, by an usurpation unexampled even in the wildest periods of heathenism, insists on seizing that which is wholly beyond human seizure – the conscience; demands that uniformity of opinion which it was never within the competency of man to enforce on man; and punishes man by the dungeon, confiscation, and death, for feelings which he can no more control, and for truths which he can no more controvert, than he can the movements of the stars.

If it has been argued that Protestantism is equally condemnatory of those who dissent from its doctrine, the obvious answer is, that it simply declares the condemnation annexed by Scripture to vice. But it attempts no execution of that punishment, leaving the future wholly to the mercy or the justice of the Judge of the quick and dead. Popery not merely passes the sentence, but executes it, as far as can be done by man. Thus the distinction is, that Protestantism goes no further than to declare what the welfare of mankind requires to be declared. But Popery takes the judgment into its own hands; and, where it has power, punishes by confiscation and chains, by the dungeon and the grave. And the especial evil of this usurpation is, that this punishment may exist, not for notorious vice, but for conspicuous virtue; not only that it takes God's office into its grasp, but that it insults the whole character of God's law. It goes farther still, and gathers within its circle of reprobation things which are wholly beyond the limit of crime – the exercise of knowledge, the right of conscience, and the sincerity of decision.

Yet, by this violent assumption of divine right, and lawless comprehension of crime, Popery has slain millions!

This distinction draws the broad line between Popery and Protestantism. The Protestant never persecutes; he is barred by his religion. The Papist never tolerates; he is stimulated by his creed. When Protestant worship is tolerated in Popish countries, the toleration is either compelled by Protestant superiority, or purchased by Popish necessities. But the claim of supremacy corrupts the whole combination. Where it is not extorted from the hands of Government, it still remains in the mind of the priesthood. Where it is blotted from the statute book, it is still registered in the breviary. Where it is extinguished by policy, it is revived by priestcraft. Like the pestilence, disappearing from the higher orders, it lurks in the rags of the populace, and waits only some new chance of earth or air, to ravage the land again. Or, like the housebreaker, hiding his head while day shines, but waiting only for nightfall to sally forth, and gather his plunder when men are vigilant no more.

The Papal Bull which has aroused such a storm of wrath in England, gives the full exemplification of this undying spirit of usurpation in Popery.

Beaten down in field and council three centuries and a half since – baffled in every attempt to domineer over England from the Reformation – in every instance sinking from depth to depth – wholly excluded from legislative power by the greatest of British kings, William III., for a hundred years of the most memorable triumphs of the constitution – Popery has now, before our eyes, to the astonishment of our understandings, and to the resistless evidence of its own passion for power, returned to all its old demands, and to more than its old demands; and, as if to make the evidence more glaring, returned at the moment when England is at the height of power, and Rome in the depth of debasement; when England is in her meridian of intelligence, and Rome in her midnight; when England is the great influential power of peace and war to all nations, and when Rome is a garrison of foreign hirelings, and her monarch the menial of their master's will.

If those demands are made, with Popery living in an actual paralysis of all the functions of sovereignty, what would be their execution with Popery lording it over the land? If Popery can issue these proclamations from the floor of its dungeon, what would be the sway of its sword when it strode over the neck of the empire? If, stript and manacled, it can thus rage against Protestantism, what would be its fury when, with new strength and unrestrained daring, its march headed by treachery in the higher orders, and followed by fanaticism in the lower, it should take possession of the Constitution?

While England was in a state of drowsy tranquillity, a Papal Bull appeared, under the signature of Cardinal Lambruschini, the Papal Secretary. A more daring document never was fabricated in the haughtiest days of Papal tyranny. It divided England into twelve Dioceses of the Popedom; it appointed twelve bishops, and appropriated to them all the rights and privileges of Episcopacy in England; and it called on all the Papists to contribute to the new pomp of the Popish worship, and the subsistence of the Diocesans.

This document is long and desultory; but as it is of importance to lay the case authentically before the reader, it shall be given in its own words, abbreviating only the formalities of the verbiage.

"Pius P. P. IX. – The power of ruling the Universal Church, committed by our Lord Jesus Christ to the Roman Pontiff in the person of St Peter, Prince of the Apostles, hath preserved through every age in the Apostolic See this remarkable solicitude, by which it consulteth for the advantage of the Catholic religion in all parts of the world, and studiously provideth for its extension. And this correspondeth with the design of its Divine founder, who, when he ordained a head to the Church, looked forward to the consummation of the world. Among other nations, the famous realm of England hath experienced the effects of this solicitude on the part of the Sovereign Pontiff."

After referring to the agency sustained by the Papacy in England from 1623, by nominal bishops, the Bull declares that, from the commencement of his pontificate, Pius had his attention fixed on the "promotion of the Church's advantage in that kingdom. Wherefore, having taken into consideration the present state of Catholic affairs in that kingdom, and reflecting on the very large and everywhere increasing number of Catholics there; considering also that the impediments which principally stood in the way of the spread of Catholicity were daily being removed, we judged that the time had arrived when the form of Ecclesiastical Government in England might be brought back to that model in which it exists freely among other nations." It seemed good to the Pope to establish his Bishops among us, as they were in Popish countries. The result is, "that in the kingdom of England, according to the common rule of the Church, we constitute and decree that there be restored the hierarchy of ordinary bishops."

Before we proceed, we must observe the quantity of assumption, even in this fragment. 1st, That Christ gave the Headship of the Universal Church, (he himself being the only Head); 2d, That St Peter was the head of the apostles, (which is contradicted by the whole apostolic history;) and 3d, That this right has always and everywhere belonged to Rome! – (a right resisted by the Greek Church, by a large portion of even the Latin Church, by the early British Church, and by the Syrian.)

It is further admitted, that a change has lately taken place in the relative conditions of English Protestantism and Popery, and that the appointment of bishops is for the purpose "of extending that change" – in other words, of acquiring power, and urging proselytism, in a Protestant state, where the Papist is tolerated only on the promise of peace.

But all disguise is now thrown aside, as if it was no longer necessary. The movement is acknowledged to be one of national conversion; religious conquest is declared to be the object; the Pope, in planting twelve new bishops in British sees, declares that he is resuming the old supremacy of Rome – thus, holding out reconciliation in one hand, and retaliation in the other, he is prepared at once to supersede the national religion.

In conformity with this declaration, he has taken the map of England into his hand; and, surrounded by his cardinals, has dissected it into dioceses in the following style: —

All England and Wales shall henceforth form one Archiepiscopal Province.

In the district of London there shall be an Archbishopric of Westminster, comprising Middlesex, Essex, and Hertfordshire.

The See of Southwark is to be suffragan to that of Westminster, and is to comprehend the counties of Berks, Southampton, Surrey, Sussex, and Kent, with the isles of Wight, Jersey, Guernsey, and the adjacent isles.

In the north there is to be the Diocese of Hexham.

The Diocese of York will be established at Beverley.

In the west, the See of Liverpool, comprehending the Isle of Man, Lonsdale, Amounderness, (?) and West Derby.

The See of Salford, comprising Blackburn and Leyland.

In Wales, there shall be the Diocese of Shrewsbury, comprising Anglesea, Caernarvon, Denbighshire, Flintshire, Merionethshire, Montgomeryshire, Cheshire, and Salop.

And the Diocese of Newport, comprising Brecknockshire, Glamorganshire, Carmarthenshire, Pembrokeshire, Monmouthshire, and Herefordshire.

The West is divided into two Bishoprics: —

Clifton, comprising Gloucestershire, Somersetshire, and Wiltshire; And Plymouth, comprising Devonshire, Dorsetshire, and Cornwall.

In the Central District, the Diocese of Nottingham shall comprise Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, and Rutlandshire.

The Diocese of Birmingham, comprising the counties of Stafford, Warwick, Worcester, and Oxford.

The Eastern district shall form one Diocese, under the name of Northampton.

Thus England shall form one Ecclesiastical Province, under one Archbishop and twelve Bishops.

They are to correspond with the College de Propagandâ Fide.

The new Bishops are to be unshackled by any previous customs of the Romish Church in England, and to have full Episcopal powers.

The Papal letter concludes by a recommendation to the Roman Catholics of England "to contribute, so far as in their power," by their pecuniary means, to the dignity of their Prelates and the "splendour of their worship," &c.

To prevent all idea that this division is merely nominal or spiritual, or unconnected with penalties on Protestantism, the principal Popish journal in England has added the following comment: —

"Rome has more than spoken; she has spoken and acted. She has again divided our land into dioceses, and has placed over each a pastor, to whom all baptized persons (!) without exception (!) within that district, are openly commanded to submit themselves in all ecclesiastical matters, under pain of damnation (!) And the Anglican Sees– those ghosts of realities long past away —are utterly ignored."

The bull proceeds: "Thus, then, in the most flourishing kingdom of England, there will be established one Ecclesiastical Province, consisting of an Archbishop or metropolitan head, and twelve Bishops, his suffragans, by whose exertions and pastoral cares we trust God will give to Catholicity in that country a fruitful and daily increasing extension.

"Wherefore we now reserve to ourselves and our successors, the Pontiffs of Rome, the power of again dividing the said province into others, and of increasing the number of dioceses, as occasion shall require; and, in general, as it shall seem fitting in the land, we may freely declare new limits to them."

Thus we find that the Pope is to hold a perpetual bag of mitres in his hand, out of which every aspirant for the honours of Rome and the lucre of England is to have his dole. Every head among us that aches for honours may now know where to look for them. Professorships and parishes need no longer keep the new school lingering on the edge of Popery; their consciences (!) may be relieved without injuring their pockets; they may allow themselves to "speak out;" and after half-a-dozen years of the most stubborn denials of Popery – of paltry protests and beggarly equivocation – of defending their orthodoxy in the press, and betraying their apostacy in the pulpit – they will be enabled to turn their backs on Protestantism, probably with a very useful addition to their resources, and start up from Curates and Canons into "My Lords." England would give very comfortable room for a speculation of this kind. Sixpence a piece from twenty millions of people would be better than all the Professorships of both Universities; and a seat in the House of Lords (which would be inevitably demanded, and which would be unhesitatingly conceded by Whig flexibility) would place the obscure and the avaricious very much at their ease.