полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 68, No 422, December 1850

Mr Laing's intimate acquaintance with the habits and condition of those countries, which now seem destined to stand in the same relation to Great Britain as Numidia did to decaying Rome, has enabled him also to point out how vain is the expectation that they will permanently extend the use of our manufactures in proportion to our consumption of their corn. No one has more forcibly shown the insanity of sacrificing, for so vague a prospect, the prosperity of those classes who chiefly maintain the home market.

"The superior importance of the home market for all that the manufacturing industry of Great Britain produces, compared to what the foreign market, including even the colonial, takes off, furnishes one of the strongest arguments against the abolition of the Corn Laws… The home consumpt, not the foreign, is undeniably that which the great mass of British manufacturing labour and capital is engaged in supplying. Take away from the home consumers the means to consume – that is, the high and artificial value of their labour, or rate of wages produced by the working of the Corn Laws – and you stop this home market. You cut off the spring from which it is fed. You sacrifice a certain home market for an uncertain foreign market. You sacrifice four-fifths for the chance of augmenting one-fifth. If the one-fifth, the foreign consumpt, should be augmented so as to equal the four-fifths – the home consumpt – it would still be a question of very doubtful policy whether it should be so augmented: whether the means of living of so large a proportion of the productive classes should be made to depend so entirely upon a demand which political circumstances might suddenly cut off," &c.36

Knowing the opinions held by Mr Laing to be thus adverse to that change of the law which virtually gave to the metayeur or proprietor of Holstein, Pomerania, or Poland, a preference in Mark Lane over the farmer of Norfolk or Lincolnshire, it was with some surprise, and some apprehension for the consistency of the author, that, in turning over the table of contents of the volume before us, we came to the following heading: – "On the abolition of the Corn Laws as a Conservative measure for the English landed interest."

The process by which he has arrived at the conclusion, that a measure confessedly so disastrous in its immediate consequences will ultimately turn out beneficial to one section at least of the landed interest, seems to be this: He thinks that, in the chief corn-growing countries of the Continent, cultivation is already so generally extended over all the soils capable of yielding any return, that the land cannot, in any circumstances, give employment to a greater number of the inhabitants than it does already; whereas Great Britain contains, in his opinion, a much larger proportional area of improvable soil, which forms a reserve or provision for the future increase of our population. A succession of bad harvests in Germany or France, or any considerable addition to their present population, would necessarily reduce these countries, he believes, to extreme famine and misery; because, the land being already fully occupied and filled up, and their surplus numbers having no considerable outlet in manufacturing or commercial industry, they have no resources to fall back upon in seasons of calamity. But in England there still remains a large extent of "woods, and groves planted and preserved for ornament, parks, pleasure-grounds, lawns, shrubberies, old grass-fields producing only crops for luxury, such as pasture and hay for the finer breeds of horses;" while a still larger area of arable ground is left uncultivated in Ireland and Scotland. Hence, as our population increases, we possess a safety-valve in our untilled soil which does not exist on the Continent; we have still the means of subsisting our daily-increasing numbers; and, so long at least as these means last, it is probable that the owners of the already cultivated lands will be left in the peaceable enjoyment of their property. But that possession would not have been secure had the abolition of the Corn Laws not been conceded at the time it was – the people might have driven the landowners from their occupations, as they did in the first French Revolution; "the free importation of food has averted a similar social convulsion, and has deprived the agitator and hireling speech-maker of his plea of oppression from class interests, and conventional laws in favour of the landowners."37 These seem to be the grounds on which Mr. Laing regards the abolition of the Corn Laws as a Conservative measure – "which will preserve, for some generations at least, to our nobility, gentry, and landed interests, their domains, their estates, and their proper social interests."

As this line of defence seems to be a favourite one with the straggling remnant of that party, who, having been the immediate instruments by which the change was effected, nevertheless still venture to claim for themselves the title of Conservatives, we may shortly review the grounds on which it rests. So far as Mr. Laing's adoption of it is concerned, we may remark that the conclusion, taken by itself, is not absolutely incongruous with that disapproval of the measure of 1816 which the author has elsewhere expressed so strongly; because, in fact, he regards the question from two very different points of view. The political philosopher occupies a very different standing ground from a minister or senator. From his speculative elevation, his eye passes over the events and consequences nearest to him, and strives to penetrate the dim possibilities of the future; and if we look at human events from this ground, there are perhaps few even of the severest public calamities that are not followed by some compensatory, though it may be distant, benefit. If we can shut our eyes to the wretchedness and desolation caused by a great fire in a crowded town, we may look forward to a time when the narrow alleys and unwholesome dwellings, now in ruins before us, shall be replaced by roomy and well-built habitations, and we may perhaps consider the prospective health and comforts of the next occupants as counterbalancing the present misery. It may or it may not prove true, that the concession of 1816 will put an end to disaffection, and be remembered for generations to come in the hearts of a contented and grateful people; it may or it may not secure the aristocracy in the peaceable enjoyment of their patrimonial estates and privileges.

These, however, are results that every one will admit to be at least problematical, while there can be no doubt whatever as to the direct and immediate consequences of the measure. The most obstinate partisan no longer ventures to question the distress and ruin that is every day spreading among the larger section of the British people – the labourers, tenant farmers, and smaller landowners. And now the sufferers are told to make the most of what is left to them, and be thankful that they have escaped a revolution. It may, perchance, occur to them to question whether, in regard to their property at least, the chances of a revolution would have made their condition much worse than it is at present. Looking at the estimates of the depreciation of their possessions, which have been so triumphantly paraded by their enemies, they may be inclined to doubt whether an insurrection, or even a foreign invasion, would have cost them greatly more than ninety-one millions a-year. To the humbler and most oppressed section of the agricultural body, the congratulation on their escape from a worse fate than that they now complain of, may sound not unlike the exhortation of a highwayman who, having stripped his victim of his cash, bids him bless his stars that he is allowed to get off with whole bones, and a coat to cover them. It is true, indeed, that the pressure is not so severely felt by the lords of great domains – cannot indeed be so; for to the owner of £10,000 a-year the loss of one-fourth of his income – though it may oblige him to curtail his expenses in matters of external show, still leaves ample means for the gratification of his accustomed habits and tastes. But what comfort is it to the owner of a small estate, who is reduced to the necessity of selling it for what it will bring – perhaps for some such price as we see recorded in the transactions of the Encumbered Estates Court of Dublin – or to the farmer, who is preparing to carry his family and the remnant of his capital to some other land – or to the labourer, who finds his earnings cut down to 6s. 6d. a-week – what consolation is it to men so circumstanced, that the policy which has caused their ruin may possibly enable the great territorial lords to retain their overgrown estates, and the privileges of their order, "for some generations to come?" Mr Laing, observe, does not venture to anticipate more than a respite for them; and some will be disposed to doubt whether even their permanent safety, and the perpetuation of their rights, would not be too dearly purchased at the price we are now paying for it in the ruin of a far more numerous, and perhaps not less valuable, class of the community. We have often had occasion to express our opinion as to the alleged crisis of 1846, which is said to have been so opportunely averted – as well as to the principle which ought to animate a Government in meeting such difficulties. We are not of those who think the main business of a cabinet is to keep on good terms with "the agitator and hireling speech-maker," – and that he is the wisest minister who is most adroit in timing his concessions, and casting off his principles at the moment they become inconvenient. Any seeming tranquillity, any truce with the enemies of constitutional order purchased by such a policy, can never be otherwise than temporary and precarious, because, it is insincere – insincere on both sides – a hollow compromise between principle and the expediency of the hour.

When we look to the reasons Mr Laing gives for the opinion we have been commenting on, they will be found to hang together rather loosely. They pre-suppose that agitation de rebus frumentariis, and specially the agitation of the League, could only proceed from the pressure of want. Now, the very week that the Bill passed, the price of wheat was 52s. 2d. – which, curiously enough, is the exact sum fixed on by Mr Wilson as the natural price of wheat in England. At that time beef was selling in London at 7s. 3d. a stone. The corn averages for the whole previous year were a fraction over 49s. 6d. The average of the ten previous years was 56s. 6d., which, by another strange coincidence, corresponds to a sixpence with the price admitted by Sir Robert Peel. With such rates of the chief articles of subsistence, how can it be said that scarcity was the cause of the Corn-Law agitation? The idea of famishing millions imploring bread may have been an appropriate figure of speech in the rabid cantations of an Ebenezer Elliot; but who seriously believes that the cry of "abolition" was the voice of a starving people, and not the mere watchword of a faction? Scarcity was only the pretext for the clamour before which the Government yielded; and is there any one weak or sanguine enough to believe that, by removing that pretext, and yielding to that clamour, we have silenced the voice of discontent, and ruined the trade of the demagogue? Is agrarian agitation no longer possible? Can we shut our eyes to what is even now passing in the north of Ireland? The fire which we are told was finally extinguished in 1846, has reappeared in that quarter, and already the sparks from it are kindling up in other parts of the empire. The demand for what is called "fixity of tenure" is but the germ of a new agitation, the future phases of which, unless it shall be met in a very different spirit from that which has characterised our recent policy, it is not difficult to foresee. It will become the new rallying point of disaffection – the centre of inflammatory action. The old machinery of the League will be set up anew, and the passions of the people will again be excited by a course of studious and systematic irritation. Ministers will hesitate, deprecate, and dally with the difficulty; rival statesmen will by turns fan the flame, or feebly resist it, as suits the party tactics of the day; until, at length, some one more yielding or less scrupulous than his competitors, will discover that the demand is founded on justice and sound policy – will concede all that is asked of him, and finally will turn round complacently and claim the gratitude of his country for having saved it from a revolution.

Our view, then, of this vindication of abolition, on the ground that it has averted a social convulsion, is briefly this. The discontent which then prevailed was not, as it pretended to be, the consequence of scarcity and dearness of provisions, or of any real grievance, but was in truth produced and fostered by artificial influences, which may at any time be again called into action. The spirit of agitation which then found a convenient pretext in the corn duties, will not fail to find an equally fit handle to lay hold of on the next favourable opportunity; and it is vain, therefore, to hope that we have purchased by our concessions a lasting immunity from disturbance, or any enduring guarantee for the safety of property on its present basis. It is on grounds of justice, and not of mere statecraft, that so great a question must be argued. Had the corn-laws been founded on injustice and partiality, that surely was in itself an ample and all-sufficient reason for sweeping them away. But if, on the contrary, they were productive of no such injustice to the people at large – if equity, as well as the implied guarantee of a long succession of laws, demanded an adherence to their principle as a partial compensation for the disproportionate burdens we have imposed on the land – then the allegation that their maintenance might have produced a popular outbreak, is, after all, but a feeble and ambiguous defence for the Ministry who so readily surrendered them. The coup d'état which we are now asked to applaud as the crowning act of Conservative wisdom, sinks into a mere wily evasion of a difficulty by giving over the interests of the weaker party as a peace-offering to the more clamorous – a sacrifice of established rights to the "civium ardor prava jubentium."

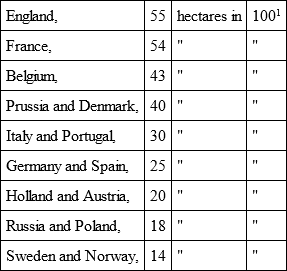

It is quite true, as Mr Laing tells us, that there exists a very large reserve of available land in Great Britain – a reserve quite sufficient, under proper management, to maintain our population for centuries to come, even at its present large ratio of increase. But that there is no similar reserve on the Continent, we beg leave to doubt. The statement may be true as regards those districts to whose condition Mr Laing has paid most attention. It may be true of France, and the peasant-cultivated parts of West Prussia, and the North of Germany; but can we say that the countries watered by the Vistula, the Bug, the Dniester – can we say that Livonia, Volhynia, Podolia – that those vast districts whose produce reaches us through Odessa, (whence it was shipped to England last winter, at a freight of 6s. a-quarter,) are already cultivated up to the full measure of their capabilities? The following comparative statement of the proportion which the cultivated land bears to the superficial extent of the different countries of Europe, is taken from the Annuaire Statistique for 1850: —

1The estimate for this country is clearly too small. Out of one hundred acres in England, seventy-eight are under cultivation, or in meadow. For the British Islands, the proportion is about sixty-four to one hundred. As to the extent of uncultivated but available land in Prussia, see the Evidence of Mr Banfield before the Committee of the House of Lords on Burdens affecting Land.

Unless we assume, (which we have no right to do,) that the extent of irreclaimable mountain, marsh, and sand, is much greater in proportion to the area of Belgium, Prussia, and Germany, the countries chiefly referred to by Mr Laing, than it is in Britain, we apprehend that their reserve is, to say the least, considerably larger than ours. We must notice also, that our author seems to regard the unreclaimed land of Britain as if it were a fund on which we can fall back at any time, when unfavourable harvests abroad shall have curtailed our accustomed supplies from the countries of the Continent. But a little consideration will show that, after we have once learnt to trust to annual foreign supplies, it is utterly vain to expect that their occasional deficiency will be supplemented, in case of emergency, from our own spare resources. Land is not like the instruments of production employed by the manufacturer. People talk of having recourse to our less fertile soils, as if it were a matter as easily and speedily accomplished as setting a mill in motion by raising the sluice. But the ponderous machine of agriculture is not so easily set a-going. On unreclaimed soils, an expenditure of from £12 to £25 an acre is required at the very outset. Fences and houses have to be erected, roads and drains to be formed, roots to be grubbed up, stones to be removed, before even the seed can be placed in the ground. Taking the farmer's capital into account, we are probably within the mark when we assert that £26 an acre, on the average, must be laid out on new land, before a single bushel can be reaped from it; and, even when ready for a rotation, an additional preparation of two or three years is necessary to bring it into a state for bearing wheat. Now, is there any speculator so insane as to risk such an expenditure on the possible chance of an occasional and simultaneous failure of the crops on the Continent? Even if grain were at a famine price, will any one be found to throw away his money in ploughing up "lawns, woods, shrubberies, village greens, and waste corners," when the very next season may see our ports swarming as usual with foreign grain ships, and "buyers firm" at 35s. a quarter?

A bad harvest is not an event that can be foreseen, and provided against, in the same way that the thrifty housekeeper lays in an additional stock of fuel, when there is talk of a strike among the colliers. The calamity is upon us long before the most skilful and far-sighted husbandman can arrange his plans and modify his rotations for the purpose of meeting the emergency. It is out of the question, then, under the present system at least, to talk of our spare land as if it were a spare coach-horse, or a spare pair of breeches, ready for use at any moment. We have taken away the only incitement to improvement, by taking care that it shall never be profitable. We have dammed back from our own fields that fertilising stream which is now spreading over and enriching the land of our neighbours. And now that we have chosen to throw ourselves on the resources of other nations – now that we may say, as the Romans did in the days of Claudian, "pascimur arbitrio Mauri" – we must not wonder if occasionally the supply turns out to be insufficient. We do not apprehend that a general scarcity can be of very frequent occurrence; but of this we may rest assured, that when it does happen, there is no portion of Europe in which the scourge of famine will be so severely felt as in this island, and it will then be utterly vain to look for relief from an expansion of that native agriculture which we have been at such pains to cripple and discourage.

We should convey to our readers a very incorrect notion of Mr Laing's work, if we led them to believe that it is wholly occupied with such subjects as we have been discussing. The commercial, military, and administrative systems of European governments certainly form his most important themes; but his remarks on the arts, customs, and literature of those countries are always amusing, and uttered with a straightforward and fearless disregard of what other people have said upon the same topic. He has no respect for conventional opinions in matters of taste; and he avows an English preference for the solid utilities and material comforts of everyday life over mere ornament. In fact, his views on the fine arts generally, are, to say the least, rather peculiar. The art of fresco-painting seems somehow to excite his bile more than anything else. His aversion to it is as intense and contemptuous as that with which Cobbett regarded the opera. It is clear to us that his digestive organs must have been fearfully disordered during his visit to Munich. From the Pinakothek to the spittoons in the Hall of the Graces, nothing seems to have pleased him – all is tawdry hollow, and out of place – and that æsthetic refinement which the ex-king of Bavaria took under his especial protection is, in his eyes, opposed to all common sense and true civilisation. We cannot join him in regarding the art of the upholsterer as more important than that of the sculptor, or in thinking the possession of hearth-rugs and window-curtains, and plenty of earthenware utensils, truer tests of national civilisation than libraries and picture-galleries. But, to a certain extent, we are disposed to share in his distrust of the genuineness of that progress in art which depends on Government encouragement. The taste which is reared and stimulated in the artificial air of palaces, instead of attaining a healthy and vigorous development, often yields little fruit except empty mannerisms. And, if the labours of the painter and the sculptor be apt to take a questionable direction under courtly tutelage, there is still more room to doubt whether any important progress in manufactures, or the mechanical arts, can be prompted by princely patronage, however well designed. We have already had proof in England of what enterprise and ingenuity can accomplish without such aid – it remains to be seen what advancement they are to make in the leading-strings of court favour, and under the inspiration of puffs in the Times newspaper, and promises of medals, with suitable inscriptions, and the bustling exertions of a semi-official staff of attachés.

Notwithstanding his heretical notions about the value of the fine arts, in a national point of view, Mr Laing's pictures of Continental life and scenery, and his criticisms on foreign manners and customs, will be found full of information and instruction, even by those who have resided for years in the countries he describes.

WHO ROLLED THE POWDER IN?

A LAY OF THE GUNPOWDER PLOT["Upon this the conversation dropped, and soon afterwards Tresham departed. When he found himself alone, he suffered his rage to find vent in words. 'Perdition seize them!' he cried: 'I shall now lose two thousand pounds, in addition to what I have already advanced; and, as Mounteagle will not have the disclosure made till the beginning of November, there is no way of avoiding payment. They would not fall into the snare I laid to throw the blame of the discovery, when it takes place, upon their own indiscretion. But I must devise some other plan.'" – Ainsworth's Life and Times of Guy Fawkes.]

They've done their task, and every caskIs piled within the cell:They've heaped the wood in order good,And hid the powder well.And Guido Fawkes, who seldom talks,Remarked with cheerful glee —"The moon is bright – they'll fly by night!Now, sirs, let's turn the key."The wind without blew cold and stout,As though it smelt of snow —But was't the breeze that made the kneesOf Tresham tremble so?With ready hand, at Guy's command,He rolled the powder in;But what's the cause that Tresham's jawsAre chattering to the chin?Nor wine nor beer his heart can cheer,As in his chamber loneHe walks the plank with heavy clank,And vents the frequent groan."Alack!" quoth he, "that this should be —Alack, and well-a-day!I had the hope to bring the Pope,But in a different way."I'd risk a rope to bring the PopeBy gradual means and slow;But Guido Fawkes, who seldom talks,Won't let me manage so.That furious man has hatched a planThat must undo us all;He'd blow the Peers unto the spheres,And throne the Cardinal!"It's time I took from other bookThan his a saving leaf;I'll do it – yes! I'll e'en confess,Like many a conscious thief.And on the whole, upon my soul,As Garnet used to teach,When human schemes are vain as dreams,'Tis always best to peach!"My mind's made up!" He drained the cup,Then straightway sate him down,Divulged the whole, whitewashed his soul,And saved the British crown: —Disclosed the walks of Guido Fawkes,And swore, with pious aim,That from the first he thought him cursed,And still opined the same.Poor Guido died, and Tresham eyedHis dangling corpse on high;Yet no one durst reflect at firstOn him who played the spy.Did any want a Protestant,As stiff as a rattan,To rail at home 'gainst priests at Rome —Why, Tresham was their man!'Twas nothing though he'd kissed the ToeAbroad in various ways,Or managed rather that his wife's fatherShould bear the blame and praise.Yet somehow men, who knew him whenHe wooed the Man of Sin,Would slightly sneer, and whisper near,Who rolled the powder in?MORALIf you, dear youth, are bent on truthIn these degenerate days,And if you dare one hour to spareFor aught but "Roman Lays;"If, shunning rhymes, you read the Times,And search its columns through,You'll find perhaps that Tresham's lapseIs matched by something new.Our champion John, with armour on,Is ready now to stand(For so we hope) against the Pope,At least on English land.'Gainst foreign rule and Roman bullHe'll fight, and surely win.But – tarry yet – and don't forgetWho rolled the powder in!