полная версия

полная версияLove and Mr. Lewisham

Mr. Lewisham pulled at his moustache.

"You begin to take me. And after all, these worthy people do not suffer so greatly. If I did not take their money some other impostor would. Their huge conceit of intelligence would breed perhaps some viler swindle than my facetious rappings. That's the line our doubting bishops take, and why shouldn't I? For example, these people might give it to Public Charities, minister to the fattened secretary, the prodigal younger son. After all, at worst, I am a sort of latter-day Robin Hood; I take from the rich according to their incomes. I don't give to the poor certainly, I don't get enough. But – there are other good works. Many a poor weakling have I comforted with Lies, great thumping, silly Lies, about the grave! Compare me with one of those rascals who disseminate phossy jaw and lead poisons, compare me with a millionaire who runs a music hall with an eye to feminine talent, or an underwriter, or the common stockbroker. Or any sort of lawyer…

"There are bishops," said Chaffery, "who believe in Darwin and doubt Moses. Now, I hold myself better than they – analogous perhaps, but better – for I do at least invent something of the tricks I play – I do do that."

"That's all very well," began Lewisham.

"I might forgive them their dishonesty," said Chaffery, "but the stupidity of it, the mental self-abnegation – Lord! If a solicitor doesn't swindle in the proper shabby-magnificent way, they chuck him for unprofessional conduct." He paused. He became meditative, and smiled faintly.

"Now, some of my dodges," he said with a sudden change of voice, turning towards Lewisham, his eyes smiling over his glasses and an emphatic hand patting the table-cloth; "some of my dodges are damned ingenious, you know —damned ingenious – and well worth double the money they bring me – double."

He turned towards the fire again, pulling at his smouldering pipe, and eyeing Lewisham over the corner of his glasses.

"One or two of my little things would make Maskelyne sit up," he said presently. "They would set that mechanical orchestra playing out of pure astonishment. I really must explain some of them to you – now we have intermarried."

It took Mr. Lewisham a minute or so to re-form the regiment of his mind, disordered by its headlong pursuit of Chaffery's flying arguments. "But on your principles you might do almost anything!" he said.

"Precisely!" said Chaffery.

"But – "

"It is rather a curious method," protested Chaffery; "to test one's principles of action by judging the resultant actions on some other principle, isn't it?"

Lewisham took a moment to think. "I suppose that is so," he said, in the manner of a man convinced against his will.

He perceived his logic insufficient. He suddenly thrust the delicacies of argument aside. Certain sentences he had brought ready for use in his mind came up and he delivered them abruptly. "Anyhow," he said, "I don't agree with this cheating. In spite of what you say, I hold to what I said in my letter. Ethel's connexion with all these things is at an end. I shan't go out of my way to expose you, of course, but if it comes in my way I shall speak my mind of all these spiritualistic phenomena. It's just as well that we should know clearly where we are."

"That is clearly understood, my dear stepson-in-law," said

Chaffery. "Our present object is discussion."

"But Ethel – "

"Ethel is yours," said Chaffery. "Ethel is yours," he repeated after an interval and added pensively – "to keep."

"But talking of Illusion," he resumed, dismissing the sordid with a sign of relief, "I sometimes think with Bishop Berkeley, that all experience is probably something quite different from reality. That consciousness is essentially hallucination. I, here, and you, and our talk – it is all Illusion. Bring your Science to bear – what am I? A cloudy multitude of atoms, an infinite interplay of little cells. Is this hand that I hold out me? This head? Is the surface of my skin any more than a rude average boundary? You say it is my mind that is me? But consider the war of motives. Suppose I have an impulse that I resist – it is I resist it – the impulse is outside me, eh? But suppose that impulse carries me and I do the thing – that impulse is part of me, is it not? Ah! My brain reels at these mysteries! Lord! what flimsy fluctuating things we are – first this, then that, a thought, an impulse, a deed and a forgetting, and all the time madly cocksure we are ourselves. And as for you – you who have hardly learned to think for more than five or six short years, there you sit, assured, coherent, there you sit in all your inherited original sin – Hallucinatory Windlestraw! – judging and condemning. You know Right from Wrong! My boy, so did Adam and Eve … so soon as they'd had dealings with the father of lies!"

* * * * *At the end of the evening whisky and hot water were produced, and Chaffery, now in a mood of great urbanity, said he had rarely enjoyed anyone's conversation so much as Lewisham's, and insisted upon everyone having whisky. Mrs. Chaffery and Ethel added sugar and lemon. Lewisham felt an instantaneous mild surprise at the sight of Ethel drinking grog.

At the door Mrs. Chaffery kissed Lewisham an effusive good-bye, and told Ethel she really believed it was all for the best.

On the way home Lewisham was thoughtful and preoccupied. The problem of Chaffery assumed enormous proportions. At times indeed even that good man's own philosophical sketch of himself as a practical exponent of mental sincerity touched with humour and the artistic spirit, seemed plausible. Lagune was an undeniable ass, and conceivably psychic research was an incentive to trickery. Then he remembered the matter in his relation to Ethel…

"Your stepfather is a little hard to follow," he said at last, sitting on the bed and taking off one boot. "He's dodgy – he's so confoundedly dodgy. One doesn't know where to take hold of him. He's got such a break he's clean bowled me again and again."

He thought for a space, and then removed his boot and sat with it on his knee. "Of course!.. all that he said was wrong – quite wrong. Right is right and cheating is cheating, whatever you say about it."

"That's what I feel about him," said Ethel at the looking-glass.

"That's exactly how it seems to me."

CHAPTER XXIV.

THE CAMPAIGN OPENS

On Saturday Lewisham was first through the folding doors. In a moment he reappeared with a document extended. Mrs. Lewisham stood arrested with her dress skirt in her hand, astonished at the astonishment on his face. "I say!" said Lewisham; "just look here!"

She looked at the book that he held open before her, and perceived that its vertical ruling betokened a sordid import, that its list of items in an illegible mixture of English and German was lengthy. "1 kettle of coals 6d." occurred regularly down that portentous array and buttoned it all together. It was Madam Gadow's first bill. Ethel took it out of his hand and examined it closer. It looked no smaller closer. The overcharges were scandalous. It was curious how the humour of calling a scuttle "kettle" had evaporated.

That document, I take it, was the end of Mr. Lewisham's informal honeymoon. Its advent was the snap of that bright Prince Rupert's drop; and in a moment – Dust. For a glorious week he had lived in the persuasion that life was made of love and mystery, and now he was reminded with singular clearness that it was begotten of a struggle for existence and the Will to Live. "Confounded imposition!" fumed Mr. Lewisham, and the breakfast table was novel and ominous, mutterings towards anger on the one hand and a certain consternation on the other. "I must give her a talking to this afternoon," said Lewisham at his watch, and after he had bundled his books into the shiny black bag, he gave the first of his kisses that was not a distinct and self-subsisting ceremony. It was usage and done in a hurry, and the door slammed as he went his way to the schools. Ethel was not coming that morning, because by special request and because she wanted to help him she was going to copy out some of his botanical notes which had fallen into arrears.

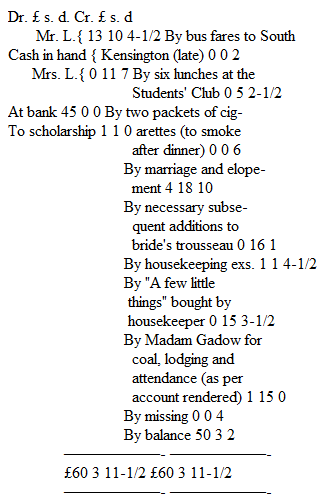

On his way to the schools Lewisham felt something suspiciously near a sinking of the heart. His preoccupation was essentially arithmetical. The thing that engaged his mind to the exclusion of all other matters is best expressed in the recognised business form.

From this it will be manifest to the most unbusiness like that, disregarding the extraordinary expenditure on the marriage, and the by no means final "few little things" Ethel had bought, outgoings exceeded income by two pounds and more, and a brief excursion into arithmetic will demonstrate that in five-and-twenty weeks the balance of the account would be nothing.

But that guinea a week was not to go on for five-and-twenty weeks, but simply for fifteen, and then the net outgoings will be well over three guineas, reducing the "law" accorded our young couple to two-and-twenty weeks. These details are tiresome and disagreeable, no doubt, to the refined reader, but just imagine how much more disagreeable they were to Mr. Lewisham, trudging meditative to the schools. You will understand his slipping out of the laboratory, and betaking himself to the Educational Reading-room, and how it was that the observant Smithers, grinding his lecture notes against the now imminent second examination for the "Forbes," was presently perplexed to the centre of his being by the spectacle of Lewisham intent upon a pile of current periodicals, the Educational Times, the Journal of Education, the Schoolmaster, Science and Art, The University Correspondent, Nature, The Athenaeum, The Academy, and The Author.

Smithers remarked the appearance of a note-book, the jotting down of memoranda. He edged into the bay nearest Lewisham's table and approached him suddenly from the flank. "What are you after?" said Smithers in a noisy whisper and with a detective eye on the papers. He perceived Lewisham was scrutinising the advertisement column, and his perplexity increased.

"Oh – nothing," said Lewisham blandly, with his hand falling casually over his memoranda; "what's your particular little game?"

"Nothing much," said Smithers, "just mooching round. You weren't at the meeting last Friday?"

He turned a chair, knelt on it, and began whispering over the back about Debating Society politics. Lewisham was inattentive and brief. What had he to do with these puerilities? At last Smithers went away foiled, and met Parkson by the entrance. Parkson, by-the-bye, had not spoken to Lewisham since their painful misunderstanding. He made a wide detour to his seat at the end table, and so, and by a singular rectitude of bearing and a dignified expression, showed himself aware of Lewisham's offensive presence.

Lewisham's investigations were two-fold. He wanted to discover some way of adding materially to that weekly guinea by his own exertions, and he wanted to learn the conditions of the market for typewriting. For himself he had a vague idea, an idea subsequently abandoned, that it was possible to get teaching work in evening classes during the month of March. But, except by reason of sudden death, no evening class in London changes its staff after September until July comes round again. Private tuition, moreover, offered many attractions to him, but no definite proposals. His ideas of his own possibilities were youthful or he would not have spent time in noting the conditions of application for a vacant professorship in physics at the Melbourne University. He also made a note of the vacant editorship of a monthly magazine devoted to social questions. He would not have minded doing that sort of thing at all, though the proprietor might. There was also a vacant curatorship in the Museum of Eton College.

The typewriting business was less varied and more definite. Those were the days before the violent competition of the half-educated had brought things down to an impossible tenpence the thousand words, and the prevailing price was as high as one-and-six. Calculating that Ethel could do a thousand words in an hour and that she could work five or six hours in the day, it was evident that her contributions to the household expenses would be by no means despicable; thirty shillings a week perhaps. Lewisham was naturally elated at this discovery. He could find no advertisements of authors or others seeking typewriting, but he saw that a great number of typewriters advertised themselves in the literary papers. It was evident Ethel also must advertise. "'Scientific phraseology a speciality' might be put," meditated Lewisham. He returned to his lodgings in a hopeful mood with quite a bundle of memoranda of possible employments. He spent five shillings in stamps on the way.

After lunch, Lewisham – a little short of breath-asked to see Madam Gadow. She came up in the most affable frame of mind; nothing could be further from the normal indignation of the British landlady. She was very voluble, gesticulatory and lucid, but unhappily bi-lingual, and at all the crucial points German. Mr. Lewisham's natural politeness restrained him from too close a pursuit across the boundary of the two imperial tongues. Quite half an hour's amicable discussion led at last to a reduction of sixpence, and all parties professed themselves satisfied with this result.

Madam Gadow was quite cool even at the end. Mr. Lewisham was flushed in the face, red-eared, and his hair slightly disordered, but that sixpence was at any rate an admission of the justice of his claim. "She was evidently trying it on," he said almost apologetically to Ethel. "It was absolutely necessary to present a firm front to her. I doubt if we shall have any trouble again…

"Of course what she says about kitchen coals is perfectly just."

Then the young couple went for a walk in Kensington Gardens, and – the spring afternoon was so warm and pleasant – sat on two attractive green chairs near the band-stand, for which Lewisham had subsequently to pay twopence. They had what Ethel called a "serious talk." She was really wonderfully sensible, and discussed the situation exhaustively. She was particularly insistent upon the importance of economy in her domestic disbursements and deplored her general ignorance very earnestly. It was decided that Lewisham should get a good elementary text-book of domestic economy for her private study. At home Mrs. Chaffery guided her house by the oracular items of "Inquire Within upon Everything," but Lewisham considered that work unscientific.

Ethel was also of opinion that much might be learnt from the sixpenny ladies' papers – the penny ones had hardly begun in those days. She had bought such publications during seasons of affluence, but chiefly, as she now deplored, with an eye to the trimming of hats and such like vanities. The sooner the typewriter came the better. It occurred to Lewisham with unpleasant suddenness that he had not allowed for the purchase of a typewriter in his estimate of their resources. It brought their "law" down to twelve or thirteen weeks.

They spent the evening in writing and copying a number of letters, addressing envelopes and enclosing stamps. There were optimistic moments.

"Melbourne's a fine city," said Lewisham, "and we should have a glorious voyage out." He read the application for the Melbourne professorship out loud to her, just to see how it read, and she was greatly impressed by the list of his accomplishments and successes.

"I did not, know you knew half those things," she said, and became depressed at her relative illiteracy. It was natural, after such encouragement, to write to the scholastic agents in a tone of assured consequence.

The advertisement for typewriting in the Athenaeum troubled his conscience a little. After he had copied out his draft with its "Scientific phraseology a speciality," fine and large, he saw the notes she had written out for him. Her handwriting was still round and boyish, even as it had appeared in the Whortley avenue, but her punctuation was confined to the erratic comma and the dash, and there was a disposition to spell the imperfectly legible along the line of least resistance. However, he dismissed that matter with a resolve to read over and correct anything in that way that she might have sent her to do. It would not be a bad idea, he thought parenthetically, if he himself read up some sound authority on the punctuation of sentences.

They sat at this business quite late, heedless of the examination in botany that came on the morrow. It was very bright and cosy in their little room with their fire burning, the gas lit and the curtains drawn, and the number of applications they had written made them hopeful. She was flushed and enthusiastic, now flitting about the room, now coming close to him and leaning over him to see what he had done. At Lewisham's request she got him the envelopes from the chest of drawers. "You are a help to a chap," said Lewisham, leaning back from the table, "I feel I could do anything for a girl like you – anything."

"Really!" she cried, "Really! Am I really a help?"

Lewisham's face and gesture, were all assent. She gave a little cry of delight, stood for a moment, and then by way of practical demonstration of her unflinching helpfulness, hurried round the table towards him with arms extended, "You dear!" she cried.

Lewisham, partially embraced, pushed his chair back with his disengaged arm, so that she might sit on his knee…

Who could doubt that she was a help?

CHAPTER XXV.

THE FIRST BATTLE

Lewisham's inquiries for evening teaching and private tuition were essentially provisional measures. His proposals for a more permanent establishment displayed a certain defect in his sense of proportion. That Melbourne professorship, for example, was beyond his merits, and there were aspects of things that would have affected the welcome of himself and his wife at Eton College. At the outset he was inclined to regard the South Kensington scholar as the intellectual salt of the earth, to overrate the abundance of "decent things" yielding from one hundred and fifty to three hundred a year, and to disregard the competition of such inferior enterprises as the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, and the literate North. But the scholastic agents to whom he went on the following Saturday did much in a quiet way to disabuse his mind.

Mr. Blendershin's chief assistant in the grimy little office in Oxford Street cleared up the matter so vigorously that Lewisham was angered. "Headmaster of an endowed school, perhaps!" said Mr. Blendershin's chief assistant "Lord! – why not a bishopric? I say," – as Mr. Blendershin entered smoking an assertive cigar – "one-and-twenty, no degree, no games, two years' experience as junior – wants a headmastership of an endowed school!" He spoke so loudly that it was inevitable the selection of clients in the waiting-room should hear, and he pointed with his pen.

"Look here!" said Lewisham hotly; "if I knew the ways of the market I shouldn't come to you."

Mr. Blendershin stared at Lewisham for a moment. "What's he done in the way of certificates?" asked Mr. Blendershin of the assistant.

The assistant read a list of 'ologies and 'ographies. "Fifty resident," said Mr. Blendershin concisely – "that's your figure. Sixty, if you're lucky."

"What?" said Mr. Lewisham.

"Not enough for you?"

"Not nearly."

"You can get a Cambridge graduate for eighty resident – and grateful," said Mr. Blendershin.

"But I don't want a resident post," said Lewisham.

"Precious few non-resident shops," said Mr. Blendershin. "Precious few. They want you for dormitory supervision – and they're afraid of your taking pups outside."

"Not married by any chance?" said the assistant suddenly, after an attentive study of Lewisham's face.

"Well – er." Lewisham met Mr. Blendershin's eye. "Yes," he said.

The assistant was briefly unprintable. "Lord! you'll have to keep that dark," said Mr. Blendershin. "But you have got a tough bit of hoeing before you. If I was you I'd go on and get my degree now you're so near it. You'll stand a better chance."

Pause.

"The fact is," said Lewisham slowly and looking at his boot toes, "I must be doing something while I am getting my degree."

The assistant, whistled softly.

"Might get you a visiting job, perhaps," said Mr. Blendershin speculatively. "Just read me those items again, Binks." He listened attentively. "Objects to religious teaching! – Eh?" He stopped the reading by a gesture, "That's nonsense. You can't have everything, you know. Scratch that out. You won't get a place in any middle-class school in England if you object to religious teaching. It's the mothers – bless 'em! Say nothing about it. Don't believe – who does? There's hundreds like you, you know – hundreds. Parsons – all sorts. Say nothing about it – "

"But if I'm asked?"

"Church of England. Every man in this country who has not dissented belongs to the Church of England. It'll be hard enough to get you anything without that."

"But – " said Mr. Lewisham. "It's lying."

"Legal fiction," said Mr. Blendershin. "Everyone understands. If you don't do that, my dear chap, we can't do anything for you. It's Journalism, or London docks. Well, considering your experience, – say docks."

Lewisham's face flushed irregularly. He did not answer. He scowled and tugged at the still by no means ample moustache.

"Compromise, you know," said Mr. Blendershin, watching him kindly. "Compromise."

For the first time in his life Lewisham faced the necessity of telling a lie in cold blood. He glissaded from, the austere altitudes of his self-respect, and his next words were already disingenuous.

"I won't promise to tell lies if I'm asked," he said aloud. "I can't do that."

"Scratch it out," said Blendershin to the clerk. "You needn't mention it. Then you don't say you can teach drawing."

"I can't," said Lewisham.

"You just give out the copies," said Blendershin, "and take care they don't see you draw, you know."

"But that's not teaching drawing – "

"It's what's understood by it in this country," said Blendershin. "Don't you go corrupting your mind with pedagogueries. They're the ruin of assistants. Put down drawing. Then there's shorthand – "

"Here, I say!" said Lewisham.

"There's shorthand, French, book-keeping, commercial geography, land measuring – "

"But I can't teach any of those things!"

"Look here," said Blendershin, and paused. "Has your wife or you a private income?"

"No," said Lewisham.

"Well?"

A pause of further moral descent, and a whack against an obstacle.

"But they will find me out," said Lewisham.

Blendershin smiled. "It's not so much ability as willingness to teach, you know. And they won't find you out. The sort of schoolmaster we deal with can't find anything out. He can't teach any of these things himself – and consequently he doesn't believe they can be taught. Talk to him of pedagogics and he talks of practical experience. But he puts 'em on his prospectus, you know, and he wants 'em on his time-table. Some of these subjects – There's commercial geography, for instance. What is commercial geography?"

"Barilla," said the assistant, biting the end of his pen, and added pensively, "and blethers."

"Fad," said Blendershin, "Just fad. Newspapers talk rot about commercial education, Duke of Devonshire catches on and talks ditto – pretends he thought it himself – much he cares – parents get hold of it – schoolmasters obliged to put something down, consequently assistants must. And that's the end of the matter!"

"All right," said Lewisham, catching his breath in a faint sob of shame, "Stick 'em down. But mind – a non-resident place."

"Well," said Blendershin, "your science may pull you through. But I tell you it's hard. Some grant-earning grammar school may want that. And that's about all, I think. Make a note of the address…"

The assistant made a noise, something between a whistle and the word