полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Benjamin Franklin

"You talk of sun-light, sir," said the foreman to Ben: "can you tell the cause of that wide difference between the light of the sun in England and America?"

Ben replied that he had never discovered that difference.

"What! not that the sun shines brighter in London than in America—the sky clearer—the air purer—and the light a thousand times more vivid—and luminous—and cheering—and all that?"

Ben said that he could not understand how that could be, seeing it was the same sun that gave light to both.

"The same sun, sir! the same sun!" replied the cockney, rather nettled, "I am not positive of that sir. But admitting that it is the same sun, it does not follow that it gives the same light in America as in England. Every thing, you know, suffers by going to the West, as the great French philosophers have proved; then why not the sun?"

Ben said he wondered the gentleman should talk of the sun going to the west.

"What, the sun not go to the west!" retorted the cockney, quite angry, "a pretty story, indeed. You have eyes, sir; and don't these show you that the sun rises in the east and travels to the west?"

"I thought, sir," replied Ben, modestly, "that your own great countryman, sir Isaac Newton, had satisfied every body that it is the earth that is thus continually travelling, and not the sun, which is stationary, and gives the same light to England and America."

Palmer, who had much of the honest Englishman about him, equally surprised and pleased to see Ben thus chastise the pride and ignorance of his foreman, put a stop to the conversation by placing a composing stick in the hands of Ben, while the journeymen gathering around, marvelled hugely to see the young North American take a composing stick in his hand!

Having spent a moment or two in running his eyes over the letter cases, to see if they were fixed as in the printing-offices in America, and glancing at his watch, Ben fell to work, and in less than four minutes finished the following—

"And Nathaniel said, can there any thing good come out of Nazareth?—Philip said, come and see."

Palmer and his workmen were petrified. Near eighty letters set up in less than four minutes, and without a blunder? And then such a delicate stroke at their prejudice and nonsense! Ben was immediately employed.

This was a fine introduction of Ben to the printing office, every person in which seemed to give him a hearty welcome; he wore his rare talents so modestly.

It gave him also a noble opportunity to be useful, which he failed not to improve.

Passing by one of the presses at which a small man, meagre and hollow-eyed, was labouring with unequal force, as appeared by his paleness and big-dropping sweat, Ben touched with pity, offered to give him "a spell." As the pressman and compositor, like the parson and the clerk, or the coffin-maker and the grave-digger are of entirely distinct trades in London, the little pressman was surprised that Ben, who was a compositor, should talk of giving him "a spell." However, Ben insisting, the little pressman gave way, when Ben seized the press, and possessing both a skill and spirit extraordinary, he handled it in such a workman-like style, that the men all declared they should have concluded he had done nothing but press-work all his life. Palmer also, coming by at the time, mingled his applauses with the rest, saying that he had never seen a fairer impression; and, on Ben's requesting it, for exercise and health sake, he permitted him to work some hours every day at press.

On his entrance into Palmer's printing-office, Ben paid the customary garnish or treat-money, for the journeymen to drink. This was on the first floor, among the pressmen. Presently Palmer wanted him up stairs, among the compositors. There also the journeymen called on him for garnish. Ben refused, looking upon it as altogether an unfair demand, and so Palmer himself, to whom it was referred, decided; insisting that Ben should not pay it. But neither justice nor patronage could bear Ben out against the spite of the journeymen. For the moment his back was turned they would play him an endless variety of mischievous tricks, such as mixing his letters, transposing his pages, breaking down his matter, &c. &c. It was in vain he remonstrated against such injustice. They all with one accord excused themselves, laying all the blame on Ralph, for so they called a certain evil spirit who, they pretended, haunted the office and always tormented such as were not regularly admitted. Upon this Ben paid his garnish—being fully convinced of the folly of not keeping up a good understanding with those among whom we are destined to live.

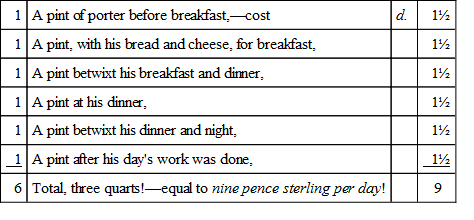

Ben had been at Palmer's office but a short time before he discovered that all his workmen, to the number of fifty, were terrible drinkers of porter, insomuch that they kept a stout boy all day long on the trot to serve them alone. Every man among them must have, viz.

A practice so fatal to the health and subsistence of those poor people and their families, pained Ben to the soul, and he instantly set himself to break it up. But they laughed him to scorn, boasting of their beloved porter, that it was "meat and drink too," and the only thing to give them strength to work. Ben was not to be put out of heart by such an argument as this. He offered to prove to them that the strength they derived from the beer could only be in proportion to the barley dissolved in the water of which the beer was made—that there was a larger portion of flour in a penny loaf; and that if they ate this loaf and drank a pint of water with it, they would get more strength than from a pint of beer. But still they would not hearken to any thing said against their darling beer. Beer, they said, was "the liquor of life," and beer they must have, or farewell strength.

"Why, gentlemen," replied Ben, "don't you see me with great ease carry up and down stairs, a large form of letters in each hand; while you, with both hands, have much ado to carry one? And don't you perceive that these heavy weights which I bear produce no manner of change in my breathing, while you, with only half the weight, cannot mount the stairs without puffing and blowing most distressingly? Now is not this sufficient to prove that water, though apparently the weakest, is yet in reality the strongest liquor in nature, especially for the young and healthy?"

But alas! on most of them, this excellent logic was all thrown away.

"The ruling passion, be it what it will—The ruling passion governs reason still."Though they could not deny a syllable of Ben's reasoning, being often heard to say that, "the American Aquatic (or water drinker) as they called him, was much stronger than any of the beer drinkers," still they would drink.

"But suppose," asked some of them, "we were to quit our beer with bread and cheese for breakfast, what substitute should we have?"

"Why, use," said Ben, "the substitute that I do; which is a pint of nice oat-meal gruel brought to me from your beer-house, with a little butter, sugar and nutmeg, and a slice of dry toast. This, which is more palatable and still less costly than a pint of beer, makes a much better breakfast, and keeps the head clearer to boot. At dinner I take a cup of cold water, which is the wholesomest of all beverages, and requires nothing but a little use, to render it as pleasant. In this way, gentlemen, I save nine pence sterling every day, making in the year nearly three thousand pence! an enormous sum, let me tell you, my friends, to a small family; and which would not only save parents the disgrace of being dunned for trifling debts, but also procure a thousand comforts for the children."

Ben did not entirely lose his reward, several of his hearers affording him the unspeakable satisfaction of following his counsel. But the major part, "poor devils," as he emphatically styled them, "went on to drink—thus continuing all their lives in a state of voluntary poverty and wretchedness!!"

Many of them, for lack of punctuality to pay the publican, would often have their porter stopped.—They would then apply to Ben to become security for them, their light, as they called it, being out. I never heard that he upbraided them with their folly; but readily gave his word to the publican, though it cost him the trouble of attending at the pay-table, every Saturday night, to take up the sums he had made himself accountable for.

Thus, by virtue of the right education, i.e. a good trade, and early fondness for labour and books, did Ben rise, like a young swan of heaven, above the dark billows of adversity; and cover himself with glory in the eyes of these young Englishmen, who had at first been so prejudiced against him. And, better still, when night came, instead of sauntering with them to the filthy yet costly ale-houses and porter cellars, he hastened to his little chamber at his frugal boarding-house, (only 1s. 6d. per week) there to enjoy the divine society of his books, which he obtained on hire from a neighbouring book-store. And commanding, as he always did, through his steadiness and rapidity at work, all the quick off-hand jobs, generally the best paid, he might have made money and enjoyed great peace; but alas! there was a moth in his purse which kept him constantly poor; a canker in his peace which filled his life with vexation. That canker and that moth was his young friend Ralph, whom, as we have seen, he had made an infidel of in Philadelphia; and for which good office, Ralph, as we shall presently see, requited him as might have been expected.

CHAPTER XXVII

"Who reasons wisely, is not therefore wise;His pride in reasoning, not in acting, lies."Some years ago a certain empiric whispered in the ear of a noble lord, in the British parliament, that he had made a wonderful discovery.

"Aye," replied the nobleman, staring; "a wonderful discovery, say you!"

"Yes, my lord, a wonderful discovery indeed! A discovery, my lord, beyond Gallileo, Friar Bacon, or even the great sir Isaac Newton himself."

"The d–l! what, beyond sir Isaac?"

"Yes, 'pon honour, my lord, beyond the great sir Isaac. 'Tis true his attractions and gravitations and all that, are well enough; very clever things to be sure, my lord; but still nothing in comparison of this."

"Zounds, man, what can it be?"

"Why, my lord—please come a little this way—now, in confidence, my lord—I've been such a lucky dog as to discover the wondrous art of raising a breed of sheep without wool!"

The nobleman, who, it is thought, was not very nearly related to Solomon, had like to have gone into fits. "What sir," asked he, with a countenance wild-staring with amazement, "a breed of sheep without wool! impossible!"

"Pardon me, my lord, it is very possible, very true. I have indeed, my lord, discovered the adorable art of raising a breed of sheep without a lock of wool on their backs! not a lock, my lord, any more than there is here on the back of my hand."

"Your fortune is made, sir," replied the nobleman, smacking his hands and lifting both them and his eyes to heaven as in ecstasy—"Your fortune is made for ever. Government, I am sure, sir, will not fail suitably to reward a discovery that will immortalize the British nation."

Accordingly, a motion to that purpose was made in the House of Lords, and the empiric was within an ace of being created a peer of the realm; when, most unfortunately, the duke of Devonshire, a district famed for sheep, got up and begged a little patience of the house until it could be fully understood what great benefit the nation was to derive from a flock of sheep without wool. "Why, zounds! my lords," said the noble duke, "I thought all along that wool was the main chance in a flock of sheep."

A most learned discussion ensued. And it being made apparent to the noble lords, that wool is actually the basis of broadcloths, flannels, and most other of the best British manufactures—and it being also made apparent to the noble lords, which was another great point gained, that two good things are better than one, i.e. that wool and mutton together, are better than mutton by itself, or wool by itself, the motion for a title was unanimously scouted: and in place of a pension the rascal had like to have got a prison, for daring thus to trump up a vile discovery that would have robbed the world of one its greatest comforts.

Just so, to my mind at least, it fares with all the boasted discoveries of our modern atheists. Admitting that these wonderful wizards could raise a nation of men and women without religion, as easily as this, their brother conjurer, could a breed of Merinos without wool—still we must ask cui bono? that is, what good would it be to the world? Supposing they could away at a dash, with all sense of so glorious a being as God, and all comfort of so mighty a hope as heaven, what benefit would it bring to man or beast?

But, God be praised, this dismal question about the consequence of discarding religion need not be asked at this time of day. These gentlemen without religion, like bell-wethers without wool, do so constantly betray their nakedness, I mean their want of morality, that the world, bad as it is, is getting ashamed of them. Here, for example, is master Ralph, who, for reasons abundantly convenient to himself, had accompanied Ben to London—Ben, as he himself confesses, had lent a liberal hand to make Ralph a sturdy infidel, that is, to free him from the restraints of the gospel. Now mark the precious fruits of this boasted freedom. Getting displeased with the parents of a poor girl, whom he had married, he determines to quit her for ever, as also a poor unoffending child he had by her, whom, by the ties of nature, he was bound to comfort and protect! Ben, though secretly abhorring this villany of Ralph, yet suffered himself to be so enamoured of his vivacity and wit, as to make him an inmate. "We were," says Ben, "inseparable companions." Very little cause had he, poor lad! as he himself owns afterwards, to boast of this connexion. But it was fine sport for Ralph; for having brought no money with him from America but what just sufficed to pay his passage, and knowing what a noble drudge Ben was, and also that he had with him fifteen pistoles, the fruits of his hard labours and savings in Philadelphia, he found it very convenient to hang upon him; not only boarding and lodging at his expense, and at his expense going to plays and concerts, but also frequently drawing on his dear yellow boys, the pistoles, for purposes of private pleasure.

If the reader should ask, how Ralph, even as a man of honour, could reconcile it to himself, thus to devour his friend, let me, in turn, ask what business had Ben to furnish Ralph the very alphabet and syntax of this abominable lesson against himself? And, if that should not be thought quite to the point, let me ask again, where, taking the fear of God out of the heart, is the difference between a man and a beast? If man has reason, it is only to make him ten-fold more a beast. Ralph, it is true, did no work; but what of that? He wrote such charming poetry—and spouted such fine plays—and talked so eloquently with Ben of nights!—and sure this was a good offset against Ben's hard labours and pistoles. At any rate Ralph thought so. Nay, more; he thought, in return for these sublime entertainments, Ben ought to support not only him, but also his concubine. Accordingly he went and scraped acquaintance with a handsome young widow, a milliner, in the next street: and what with reading his fine poetry to her, and spouting his plays, he got so completely into her good graces, that she presently turned actress too; and in the "comedy of errors," or "all for love," played her part so unluckily, that she was hissed from the stage, by all her virtuous acquaintance, and compelled to troop off with a big belly to another neighbourhood, where Ralph continued to visit her.

The reader will hardly wonder, when told that Ralph and his fair milliner soon found the bottom of Ben's purse. He will rather wonder what sort of love-powder it was that Ben took of this young man that could, for such a length of time, so fatally have befooled him. But Ben was first in the transgression. Like Alexander the coppersmith, he had done Ralph "much harm," and "God, who is wiser than all, had ordained that he should be "rewarded according to his works.

CHAPTER XXVIII

"Learn to be wise from others' ill,"And you'll learn to do full well."As nothing is so repellant of base minds as poverty, soon as Ralph found that Ben's pistoles were all gone, and his finances reduced to the beggarly ebb of living from hand to mouth, he "cleared out," and betook himself into the country to teach school, whence he was continually writing fine poetical epistles to Ben, not forgetting in every postscript, to put him in mind of his dear Dulcinea, the fair milliner, and to commend her to his kindness. As to Ben, he still persevered, after Ralph's departure, in his good old habits of industry and economy—never indulging in tobacco or gin—never sauntering to taverns or play houses, nor at any time laying out his money but on books, which he always visited, as frugal lovers do their sweethearts, at night. But still it would not all do. He could lay up nothing. The daily postage of Ralph's long poetical epistles, with the unceasing application of the poor milliner, kept his purse continually in a galloping consumption. At length he obtained a release from this unpleasant situation, though in a way that he himself never could think of afterwards without a blush.

After very frequent loans of money to her, she came, it seems, one night to his lodgings on the old errand—to borrow half a guinea! when Ben, who had been getting too fond of her, took this opportunity to offer freedoms which she highly resented.

This Ben tells himself, with a candour that will for ever do him credit among those who know that the confession of folly is the first step on the way to wisdom.

"Having, at that time," says he, "no ties of religion upon me, and taking advantage of her necessitous situation, I attempted liberties (another great error of my life,) which she repelled with becoming indignation. She informed Ralph; and the affair occasioned a breach between us. When he returned to London, he gave to understand that he considered all the obligations he owed me as annihilated by this proceeding; and that I was not to expect one farthing of all the monies I had lent him."

Ben used to say, many years afterwards, that this conduct of his friend Ralph put him in mind of an anecdote he had some where heard, of good old Gilbert Tenant: the same that George Whitefield generally called hell-fire Tenant. This eminent divine, believing fear to be a much stronger motive with the multitude than love, constantly made a great run upon that passion in all his discourses. And Boanerges himself could hardly have held a candle to him in this way. Nature had given him a countenance which he could, at will, clothe with all the terrors of the tornado. And besides he had a talent for painting the scenes of dread perdition in such colours, that when aided by the lightning of his eyes, and the bursting thunders of his voice, it was enough to start the soul of lion-hearted innocence; what then of rabbit-livered guilt? The truth is, he wrought miracles in New-Jersey: casting out devils—the devils of drunkenness, gambling, and lust, out of many a wretch possessed.

Among the thousands whom he thus frightened for their good, was a tame Indian of Woodbury, who generally went by the name of Indian-Dick. This poor savage, on hearing Mr. Tenant preach, was so terrified, that he fell down in the meeting house, and roared as if under the scalping knife.

He lost his stomach: and even his beloved bottle was forgotten. Old Mr. Tenant went to see Dick, and rejoiced over him as a son in the gospel;—heartily thanking God for adding this Indian Gem to the crown of his glory.

Not many days after this, the man of God took his journey through the south counties of New-Jersey, calling the poor clam-catchers of Cape May to repentance. As he returned and drew near to Woodbury, lo! a great multitude! He rejoiced in spirit, as hoping that it was a meeting of the people to hear the word of God: but the uproar bursting upon his ear, put him in doubt.

"Surely," said he, "this is not the voice of praise; 'tis rather, I fear, the noise of drunkenness." And so it was indeed; for it being a day of election, the friends of the candidates had dealt out their brandy so liberally that the street was filled with sots of every degree, from the simple stagger to the dead drunk. Among the rest, he beheld his Indian convert, poor Dick, under full sail in the street, reeling and hallooing, great as a sachem. Mr. Tenant strove hard to avoid him; but Dick, whose quick eye had caught the old pie-balled horse that Tenant rode on, instantly staggered towards him. Tenant put forth all his horsemanship to avoid the interview. He kicked old Pie-ball in one flank, and then in the other; pulled this rein and then that; laid on here with his staff, and laid on there; but all would not do; unless he could at once ride down the drunken beasts, there was no way of getting clear of them. So that Dick, half shaved as he was, soon got along side of old Pie-ball, whom he grappled by the rein with one hand, and stretching forth the other, bawled out, "how do? how do, Mr. Tenant?"

Tenant could not look at him.

Still, Dick, with his arm full extended, continued to bawl, "how do, Mr. Tenant, how do?" Finding that there was no getting clear of him, Mr. Tenant, red as crimson, lifted up his eyes on Dick, who still, bold as brandy, stammered out, "High, Mr. Tenant! d-d-d-don't you know me, Mr. Tenant? Don't you know Indian Dick? Why, sure, Mr. Tenant, you are the man that converted me?"

"I converted you!" replied Tenant, nearly fainting.

"Yes, roared Dick, I'll be d-d-d-nd, Mr. Tenant, if you an't the very man that converted me."

"Poor fellow!" said Tenant, with a heavy sigh, "you look like one of my handiworks. Had God Almighty converted you, you would have looked like another guess sort of a creature."

From Ben's constantly relating this story of old Tenant and Indian Dick, whenever he mentioned the aforesaid case of Ralph's baseness, many of his acquaintance were of opinion, that Ben thereby as good as acknowledged, that at the time he took Ralph in hand, he did not altogether understand the art of converting; or, that at any rate, it would have been much better for Ralph, if, as Mr, Tenant said of Indian Dick, God Almighty had converted him. He would hardly, for the sake of a harlot, have so basely treated his best friend and benefactor.

CHAPTER XXIX

Ben resolves to return to America. – Anecdote of a rare character.

"A wit's a feather, and a chief's a rod,An honest man's the noblest work of God."Ben used, with singular pleasure, to relate the following story of his Quaker friend Denham. This excellent man had formerly been in business as a Bristol merchant; but failing, he compounded with his creditors and departed for America, where, by his extraordinary diligence and frugality, he acquired in a few years a considerable fortune. Returning to England, in the same ship with Ben, he invited all his old creditors to a dinner. After thanking them for their former kindness and assuring them that they should soon be paid, he begged them to take their seats at table. On turning up their plates, every man found his due, principal and interest, under his plate, in shining gold.

This was the man after Ben's own heart. Though he never found in Denham any of those flashes of wit, or floods of eloquence, which used so to dazzle him in Ralph, yet he contracted such a friendship for him, on account of his honesty and Quaker-like meekness, that he would often steal an hour from his books at night, to go and chat with him. And on the other hand, Ben's steady and persevering industry, with his passion for knowledge, had so exalted him in Denham's esteem, that he was never better pleased than when his young friend Franklin, as he always called him, came to see him. One night Denham asked Ben how he would like a trip to America?