полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Lyman Trumbull

The office-seeking fraternity were mostly supporters of Davis, whose appearance as a candidate for the presidency was extremely offensive to the original promoters of the movement. As a judge of the Supreme Court his incursion into the field of politics, unheralded, but not unprecedented, was an indecorum. Moreover, his supporters had not been early movers in the ranks of reform, and their sincerity was doubted. They were extremely active, however, after the movement had gained headway, and they were able to divide the vote of Illinois into two equal parts (21 to 21), so that Trumbull's strength in the convention was seriously impaired. Davis's chances were early demolished by the editorial fraternity, who, at a dinner at Murat Halstead's house, resolved that they would not support him if nominated, and caused that fact to be made known.

Greeley's candidacy had not been taken seriously by the editors at Halstead's dinner-party. As an individual he was generally liked by them and his ability and honesty were held in the highest esteem; but he was looked upon as too eccentric and picturesque to find much support in such a sober-minded convention as ours. Adams and Trumbull were the only men supposed by us to be within the sphere of nomination, and the chances of Adams were deemed the better of the two. We had yet to learn that there are occasions and crowds where personal oddity and a flash of genius under an old white hat are more potent than high ancestry or approved statesmanship, or both those qualifications joined together.

Before nominations were made, a platform was to be framed and adopted. There were three main issues to be considered: Universal amnesty, civil service reform, and tariff reform. On the first and second there was no difference of opinion. Without them the Cincinnati movement would never have taken place; the convention would never have been called. As to the third, there was a difference of opinion which divided the convention and the Committee on Resolutions in the middle, and it soon became known that "there was no common ground on which the protectionists and revenue reformers could stand." So wrote E. L. Godkin from the convention hall to the Nation. He continued:

The Committee on Resolutions, after sitting up a whole night, were compelled to accept the compromise which he [Greeley] proposed—the reference of the whole matter to the people in the congressional districts. It is right to add that the sentiment of the convention was overwhelmingly in favor of this course. There is a touch of absurdity about it, it is true, but it is at least frank and honest, and at all events nothing else was possible. Even such outspoken free-traders as Judge Hoadley, of this city, were compelled to concur in this disposition of the question.

As chairman of the Committee on Resolutions, and a free-trader, I can confirm all that Godkin wrote, and add that the committee considered the expediency of reporting to the convention their inability to agree and asking to be discharged. This plan was rejected lest it should cause a bolting movement, on an issue which was rated only third in importance among those which had brought us together. It was decided that tariff reform could wait, while the pacification of the South and the reform of the civil service could not.

Thursday night, May 2, I had gone to bed at the Burnet House when I was aroused by a loud knock on my door and a voice outside which I recognized as that of Grosvenor exclaiming: "Get up! Blair and Brown are here from St. Louis." Without waiting for an answer he went on knocking at other doors in the corridor and giving the same warning, but no other explanation. I arose, dressed myself, and went down to the rotunda of the hotel, where I found some of the supporters of Trumbull and of Adams who were trying to discover why the arrival of Frank Blair and Gratz Brown should produce a commotion in a convention of more than seven hundred, of which Blair and Brown were not members. Blair was then the Democratic Senator from Missouri. The two newcomers were not visible. They had obtained a room and had called into it some of the Missouri delegation and would not admit any uninvited persons. Presently Grosvenor returned and told us that Brown intended to withdraw as a candidate for the presidency and turn his forces over to Greeley, and himself take the Vice-Presidency. Grosvenor considered this a dangerous combination and said that steps should be taken to checkmate it at once.

The Adams and Trumbull men here collected remained till about two o'clock trying to learn more about the expected coup, but as nothing further could be obtained they retired one by one to uneasy slumber. Grosvenor maintained to the last that great mischief was impending, but could not suggest any way to meet it.

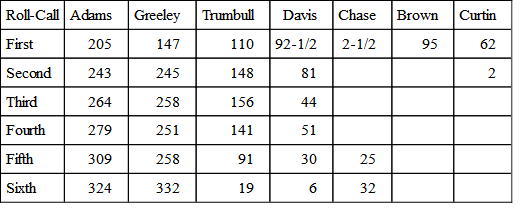

On the following day voting began, and the first roll-call showed Adams in the lead with 205 votes; Greeley had 147, Trumbull 110, Brown 95, Davis 92-1/2, Curtin 62, Chase 2-1/2. Carl Schurz, who was permanent chairman of the convention and a supporter of Adams, then rose and with some signs of embarrassment said that a gentleman who had received a large number of votes desired to make a statement, whereupon he invited the Hon. B. Gratz Brown to come to the platform. Brown advanced to the front, and after thanking his friends for their support said that he had decided to withdraw his name and that he desired the nomination of Horace Greeley as the man most likely to win in the coming election. There was great applause among the supporters of Greeley, but the immediate result did not answer their expectations. Brown could not control even the Missouri delegation. The first vote of the Missouri men had been 30 for Brown. The second was, Trumbull 16, Greeley 10, Adams 4.

All the votes are shown in the following table:

Although Greeley's plurality on the sixth roll-call was small, his gain over the fifth was large, being 74 votes, that of Adams being only 15. This was a signal to all who wished to be on the winning side to take shelter under the old white hat. Changes were made before the result was announced which gave Greeley 482 to 187 for Adams. Then Greeley was declared nominated. The nomination of Gratz Brown for Vice-President followed without much opposition.

The supporters of Adams and of Trumbull were stunned. The first impulse of their leaders, and especially of Schurz, was to put on sackcloth, and go into retirement. Prompt decision, however, was necessary to the editors of daily newspapers. Other persons could go home and take days or weeks to think the matter over, but those who, at Halstead's table, had decided against David Davis, must needs make another prompt decision before the next paper went to press. They decided to support Greeley, because they had honestly led their readers to an honest belief that the Cincinnati movement was for the best interests of the Republic; and they deemed it unfair to turn against it on account of personal vexation against a man whose candidacy had been tolerated through the whole proceedings. That Greeley was an unbalanced man we all knew. That he was liable to go off at a tangent and that his self-esteem and self-confidence might put him beyond the reach of good counsel in affairs of great pith and moment, was the unexpressed thought of most of us. But we knew that his aims were patriotic, and we reflected that some risks are taken at every presidential election. Greeley had not yet been proved an unsafe President, and that was more than could be said for Grant. In fact, Grant's second term proved to be worse than his first.

Schurz was more distressed by the "Gratz Brown trick," as it was commonly called, than by anything else. This had the appearance of a brazen political swap executed in the light of day, by which the presidency and the vice-presidency were disposed of as so much merchandise. He did not, however, in his thoughts connect Greeley with the trade. It was physically impossible that the latter could have been a party to it, if there was a trade. Nevertheless he considered the German vote lost beyond recall by the bad look of it.127 My own belief is that Blair and Brown were jealous of Schurz's power in Missouri; that they feared he would become omnipotent there, dominating both parties, if Adams should be elected President; and that the only way to head him off was to beat Adams. They chose Greeley for this purpose, not because they had any bargain with, or fondness for, him, but because he was the next strongest man in the convention.

The engineers of the Liberal Republican movement went their several ways. Those who held tariff reform of more importance than all other issues abjured Greeley at once. E. L. Godkin and William Cullen Bryant declared war against him because they considered him dangerous and unfit. The following correspondence which took place between Bryant and Trumbull was illustrative of the feelings of many others:

The Evening Post,

41 Nassau Street, Cor. Liberty,

New York, May 8th, 1872.

My dear Sir,

It has been said that you will support the nomination of Mr. Greeley for President. I have no right to speak of any course which you may take in politics in any but respectful terms, but I may perhaps take the liberty of saying that if you give that man your countenance, some of your best friends here will deeply regret it. We who know Mr. Greeley know that his administration, should he be elected, cannot be otherwise than shamefully corrupt. His associates are of the worst sort and the worst abuses of the present Administration are likely to be even caricatured under his. His election would be a severe blow to the cause of revenue reform. The cause of civil service reform would be hopeless with him for President, for Reuben E. Fenton, his guide and counselor, and the other wretches by whom Greeley is surrounded, will never give up the patronage by which they expect to hold their power. As to other public measures there is no abuse or extravagance into which that man, through the infirmity of his judgment, may not be betrayed. It is wonderful how little, in some of his vagaries, the scruples which would influence other men of no exemplary integrity, restrain him. But I need not dwell upon these matters—they are all set forth in the Evening Post which you sometimes see. What I have written, is written in the most profound respect for your public character, and because of that respect. If you conclude to support Mr. Greeley, I shall, of course, infer that you do so because you do not know him.

Yours truly,

Hon. L. Trumbull.

W. C. Bryant.

United States Senate Chamber,

Washington, May 10, 1872.

Wm. C. Bryant, Esq.,

My dear Sir,—Your kind and frank letter is before me. I wish I could see something better than to support Mr. Greeley, but I do not. Personally, I know but little of him, but in common with most people supposed he was an honest but confiding man, who was often imposed upon by those about him. This would be a great fault in a President, I admit, but with proper surroundings could be guarded against, and almost anything would be an improvement on what we have. One of the greatest evils of our time is party despotism and intolerance. Greeley's nomination is a bomb-shell which seems likely to blow up both parties. This will be an immense gain. Most of the corruptions in government are made possible through party tyranny. Members of the Senate are daily coerced into voting contrary to their convictions through party pressure. A notable instance of this was the vote on the impeachment of Johnson, and matters in this respect have not improved since. If by Greeley's election we could break up the present corrupt organizations, it would enable the people at the end of four years to elect a President with a view to his fitness instead of having one put upon them by a vote of political bummers acting in the name of party.

Having favored the Cincinnati movement and Greeley having received the nomination, I see no course left but to try to elect him, and endeavor to surround him, as far as possible, with honest men. Greeley had a good deal of strength among the people and was strong in the convention outside of bargain or arrangement. Many voted for him as their first choice, and in Illinois I feel confident he is a stronger candidate than Adams would have been.

Lyman Trumbull.

Sumner, although urged by many of his warmest friends both before and after the convention, including Frank Bird, Samuel Bowles, and Greeley himself (through Whitelaw Reid), to declare his position, did not break silence until May 31, when he made his great speech against Grant. The speech remains a true catalogue of the shortcomings of Grant as a civil administrator up to that time. All his sins of omission and of commission were there set forth in orderly array, together with the proofs. Sumner thus spared future historians a deal of trouble in searching the records, but the speech was not very effective in the way of changing votes. Sumner sometimes mistook himself for a modern Cicero impeaching Verres. He piled up the agony in the fashion customary in the pleadings of the ancient forum. He overlooked the signal services rendered by Grant before he held any civil office. He did not make allowance for the transition of a tanner's clerk, earning fifty dollars a month and having a family to support, first to the command of half a million soldiers in war time, and then to the presidency of the United States in time of peace, all within the period of eight years. The mistakes naturally arising from such crude beginnings, when meeting gigantic responsibilities in quick succession, ought to have excited pathos as well as censure. By giving due consideration to Grant's whole career, he would have secured a better hearing for the part of it which he wished to impress upon the public mind.

Even now Sumner did not advise anybody to vote for Greeley. His omission to do so was at once construed as an argument favorable to Grant. It was said that the dangers involved in Greeley's eccentricities were so much greater than anything that Grant had done, or could do, that Grant's worst enemy (Sumner) would not advise people to vote for him. Not until the 29th of July did the Massachusetts Senator publicly speak for Greeley, and then only in a letter to some colored voters who had asked his advice. It was then too late to exert much influence. It is doubtful if even the colored men who had sought his advice gave any heed to it. Probably the reason why Sumner did not speak earlier was that he hesitated to break from his abolitionist friends, Garrison, Phillips, and others, who had besought him not to join the Democrats. When he did finally join the forces supporting Greeley, his old friend Garrison turned upon him and chastised him severely in a series of open letters, which Sumner declined to read.

CHAPTER XXVI

THE GREELEY CAMPAIGN

My own feelings immediately after the nomination were set forth in a telegram to the Chicago Tribune published in its issue of May 4. The chief part was in these words:

Cincinnati, May 3.—The nomination of Mr. Greeley was accomplished by the people against the judgment and strenuous efforts of politicians, using the latter word in its larger and higher sense. The Gratz Brown performance has given the whole affair the appearance of a put-up job, but it was merely a lucky guess. The Blairs and Browns do not like Schurz. To defeat a candidate who was likely to be on confidential terms with Schurz, as either Adams or Trumbull would have been, was the thing nearest to their hearts, and for this purpose Brown made his appearance here. His speech in the Convention fell like dish-water on the whole assemblage, and, being followed by the transfer of the Missouri votes to Trumbull, instead of Greeley, showed that he had no influence in his own delegation. The changes from Brown to Greeley were few and far between, and in a short time the convention only remembered that Brown had been a candidate once and was so no longer. But the personal popularity of Greeley was more than a match for the intellectual strength of Trumbull and the moral gravity of Adams. He was stealing votes from both of them all the time. When the Illinois delegation at last perceived that the heart of the convention was carrying away the head, and retired for consultation, the surprising fact was developed that fifteen of their own number preferred Greeley to any candidate not from their own state. The supporters of Adams, while entertaining the most cordial feeling for the friends of Trumbull, think that if the latter had come over to Adams's corner the result would have been different. I do not think so. If the Illinois vote could have been cast solid for Adams at an earlier stage, the result might have been different: but there was no time when Adams could have got more than the twenty-seven votes which were finally cast for him. The contingency of having to divide between Adams and Greeley had never been considered, and, therefore, no time had been allowed to compare views. The vote of the state being thus divided, its weight was lost for any purpose of influencing other votes. Then gush and hurrah swept everything down, and, almost before a vote of Illinois had been recorded by the secretary, the dispatches came rushing to the telegraph instruments that Greeley was nominated. For a moment, the wiser heads in the convention were stunned, though everybody tried to look perfectly contented. Of all the things that could possibly happen, this was the one thing which everybody supposed could not happen. Not even the Greeley men themselves thought it could happen. The only able politician who seemed to be really for Greeley was Waldo Hutchins, of New York, and even his sincerity was questioned by Greeley's backbone friends as long as the Davis movement was regarded as still alive.

How the news was received by Trumbull was told by the New York Herald's Washington dispatch of May 3:

… The scene in the Senate, when the news was received, was one of complacent dignity, such as only the members of that body could arrange, even if they had studied to prepare themselves for an art tableau. Mr. Fenton was the recipient of the dispatches, and his chair was consequently surrounded by a crowd of the less dignified Senators, who could not wait to have the telegrams passed around. Trumbull was the most undisturbed of all those on the floor. His equanimity astonished his friends as well as the numerous strangers in the galleries, who watched closely for indications of excitement in his parchment-like face. In truth, he seemed to get the news rather by some occult process of induction, if he got it at all, than by the course usual to ordinary men. Other members smiled, made comments, exchanged opinions and preserved their dignity with customary success; but he alone asserted an immobility of demeanor that will last for all time, in the memory of its witnesses, as a remarkable instance of self-possession. At last, when every one else had delivered himself of some criticism he remarked to those in his immediate vicinity: "If the country can stand the first outburst of mirth the nomination will call forth, it may prove a strong ticket."

Carl Schurz was slow in reaching a decision to support the ticket. His first endeavor was to induce Greeley, in a friendly way, to decline the nomination, by showing him the sombre aspects of the campaign ahead. In a letter dated May 18, he told Greeley that the dissatisfaction of an influential part of the Liberal Republican forces was such that a meeting had been called to consider the question of putting another ticket in the field before the Democrats should hold their convention. Other discouraging features were presented and the letter concluded with these words:

I have, from the beginning, made it a point to tell you with entire candor how I feel and what I think about this business, and now if the developments of the campaign should be such as to disappoint your hopes, it shall not be my fault if you are deceived about the real state of things.

To this Greeley replied on the 20th, saying that his advices warranted him in predicting that New York would give 50,000 majority for the Cincinnati ticket, and that New England and the South would be nearly solid for it, while in Pennsylvania and the Northwest the chances were at least even. He ended by saying: "I shall accept unconditionally."

The meeting foreshadowed in Schurz's letter to Greeley took place at the Fifth Avenue Hotel on the 20th of June. It was composed mainly of persons who had participated in the Cincinnati Convention and had been greatly disappointed by Mr. Greeley's nomination. William Cullen Bryant presided, but fell asleep in the chair soon after the proceedings began. The first speech was made by Trumbull, who said that his mind was made up to support the Cincinnati ticket. He thought that Greeley had gained strength during the first month of the campaign and that the chances of his election were good. He could see no reason for nominating another ticket. That would simply be playing into the hands of the supporters of Grant.

Schurz's position, as reported by the Nation, was this:

That he, more than any other man, was chagrined by the result of Cincinnati; that he does not consider Mr. Greeley a reformer, and has no expectations of any reforms at his hands, and will say so on the stump; that he believes him "to be surrounded by bad men"; that he (Mr. Schurz), however, is so satisfied of the necessity of defeating Grant and dissolving existing party organizations, that he is ready to use any instrument for the purpose, and will, therefore, support Greeley in the modified and guarded manner indicated above. He looks forward, with a hopefulness bordering on enthusiasm, to the good things which will grow out of the confusion following on Greeley's election, and is deeply touched by the Southern eagerness for Greeley.

A private letter from E. L. Godkin to Schurz, dated Lenox, Massachusetts, June 28, gives reasons for deprecating the course that the latter had decided to take in the campaign.

He has considered Schurz's words about Greeley; would be most glad could he see any way to join in supporting Greeley, Schurz being the one man in American politics who inspires Godkin with some hope concerning them. He maturely considered what he could and would do when Greeley was first nominated. In view of his own share in bringing public feeling to the point of creating the convention, he would have stood by Greeley if possible; saw no chance to do so and sees none now; is satisfied he can have nothing to do with Greeley. If Greeley gave pledges, and broke them, "as I believe he would," it would be no consolation to Godkin that an opposition would thereby be raised up. He went through all this with Grant, who gave far better guarantees than Greeley offers, "and he made fine promises and broke them, and good appointments and reversed them, and I have in consequence been three years in opposition." Cannot afford to repeat this. "Greeley would have to change his whole nature, at the age of 62, in order not to deceive and betray you," and when he has done so it will be too late to atone for having backed him by turning against him, which would then merely discredit one's judgment, and invite suspicion of some personal disappointment. Moreover, the small band of political reformers will have fallen into disrepute and become ridiculous and the country will be worse off than before. Feels that Schurz is sacrificing the future in taking Greeley on any terms....

Parke Godwin was even more bitter against Greeley. He wrote to Schurz under date May 28:

"… I have so strong a sense of Greeley's utter unfitness for the presidency that I cannot well express it. The man is a charlatan from top to bottom, and the smallest kind of a charlatan,—for no other motive than a weak and puerile vanity. His success in politics would be the success of whoever is most wrong in theory and most corrupt in practice." All the most corrupt spoilsmen of either side are either with him now or preparing to go to him. It is the first of duties to expose him and his factitious reputation. Grant and his crew are bad,—but hardly so bad as Greeley and his would be. Besides, Grant, though in very bad hands, has his clutches full: Greeley's set would be newcomers.