полная версия

полная версияTen Thousand a-Year. Volume 3

"Don't be too sure of that," said Aubrey, gravely.

"Sure? I've no more doubt of it," replied Delamere, briskly, "than I have of our now being in Vivian Street—if there be the slightest pretence to fairness in a committee of the House of Commons. Why, upon my honor, we've got no fewer than eleven distinct, unequivocal, well-supported"–

"If election committees are to be framed of such people as appear to have been returned"–....

Did, however, the gaudy flower of Titmouse's victory at Yatton contain the seeds of inevitable defeat at St. Stephen's? 'T was surely a grave question; and had to be decided by a tribunal, the constitution of which, however, the legislature hath since, in its wisdom, seen fit altogether to alter. With matters, therefore, as they then were—but now are not—I deal freely, as with history.

The first glance which John Bull caught of his new House of Commons, under the Bill for giving Everybody Everything, almost turned his stomach, strong as it was, inside out; and he stood for some time staring with feelings of alternate disgust and dismay. Really, as far at least as outward appearance and behavior went, there seemed scarcely fifty gentlemen among them; and those appeared ashamed and afraid of their position. 'T was, indeed, as though the scum that had risen to the simmering surface of the caldron placed over the fierce fires of revolutionary ardor, had been ladled off and flung upon the floor of the House of Commons. The shock and mortification produced such an effect upon John, that he took for some time to his bed, and required a good deal of severe treatment, before he in any degree recovered himself. It was, indeed, a long while before he got quite right in his head!—As the new House anticipated a good deal of embarrassment from the presidency of the experienced and dignified person who had for many years filled the office of Speaker, they chose a new one; and then, breathing freely, started fair for the session.

Some fifty seats were contested; and one of the very earliest duties of the new Speaker, was to announce the receipt of "a petition from certain electors of the borough of Yatton, complaining of an undue return; and praying the House to appoint a time for taking the same into its consideration." Mr. Titmouse, at that moment, was modestly sitting immediately behind the Treasury bench, next to a respectable pork-butcher, who had been returned for an Irish county, and with whom Mr. Titmouse had been dining at a neighboring tavern; where he had drunk whiskey and water enough to elevate him to the point of rising to present several petitions from his constituents—first, from Smirk Mudflint, and others, for opening the universities of Oxford and Cambridge to Dissenters of every denomination, and abolishing the subscription to the Thirty-Nine Articles; secondly, from Mr. Hic Hæc Hoc, praying for a commission to inquire into the propriety of translating the Eton Latin and Greek grammars into English; thirdly, from several electors, praying the House to pass an act for exempting members of that House from the operation of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Laws, as well as from arrest on mesne and final process; and lastly, from certain other electors, praying the House to issue a commission to inquire into the cause of the Tick in sheep. I say this was the auspicious commencement of his senatorial career, meditated by Mr. Titmouse, when his ear caught the above startling words uttered by the Speaker; which so disconcerted him—prepared though he was for some such move on the part of his enemies, that he resolved to postpone the presentation of the petitions of his enlightened constituents, till the ensuing day. After sitting in a dreadful fright for some twenty minutes or so, he felt it necessary to go out and calm his flurried spirits with a glass of brandy and soda-water. As he was leaving the House, a little incident happened to him, which was attended with very memorable consequences.

"A word with you, sir," whispered a commanding voice, in his ear, as he felt himself caught hold of by some one sitting at the corner of the Treasury Bench—"I'll follow you out—quietly, mind."

The speaker was a Mr. Swindle O'Gibbet, a tall, elderly, and somewhat corpulent person, with a broad-brimmed hat, a slovenly surtout, and vulgar swaggering carriage; a ruddy shining face, that constantly wore a sort of greasy smile; and an unctuous eye, with a combined expression of cunning, cowardice, and ferocity. He spoke in a rich brogue, and with a sort of confidential and cringing familiarity; yet, withal, 't was with the air and the tone of a man conscious of possessing great direct influence out of doors, and indirect influence within doors. 'T was, in a word, at once insinuating and peremptory—submissive and truculent. Several things had concurred to give Titmouse a very exalted notion of Mr. O'Gibbet. First, a noble speech of his, in which he showed infinite "pluck" in persevering against shouts of "order" from all parts of the House for an hour together; secondly, his sitting on the front bench, often close beside little Lord Bulfinch, the leader of the House. His Lordship was a Whig; and though, as surely I need hardly say, there are thousands of Whigs every whit as pure and high-minded as their Tory rivals, his Lordship was a very bitter Whig. The bloom of original Whiggism, however, ripening fast into the rottenness of Radicalism, gave out at length an odor which was so offensive to many of his own early friends, that they were forced to withdraw from him. Personally, however, he was of respectable character, and a man of considerable literary pretensions, and enjoyed that Parliamentary influence generally secured to the possessor of talent, tact, experience, and temper. Now, it certainly argued some resolution in Mr. O'Gibbet to preserve an air of swaggering assurance and familiarity beside his aristocratic little neighbor, whose freezing demeanor towards him—for his Lordship evinced even a sort of shudder of disgust when addressed by him—Mr. O'Gibbet felt to be visible to all around. Misery makes strange bed-fellows, but surely politics stranger still; and there could not have been a more striking instance of it, than in Lord Bulfinch and Mr. O'Gibbet sitting side by side—as great a contrast in their persons as in their characters. But the third and chief ground of Titmouse's admiration of Mr. O'Gibbet, was a conversation—private and unheard the parties had imagined it, in the lobby of the House; but every word whereof had our inquisitive, but not excessively scrupulous, little friend contrived to overhear—between Mr. O'Gibbet and Mr. Flummery, a smiling supple Lord of the Treasury, and whipper-in of the Ministry. Though generally confident enough, on this occasion he trembled, frowned, and looked infinitely distressed. Mr. O'Gibbet chucked him under the chin, familiarly and good-humoredly, and said—"Oh, murther and Irish! what's easier?—But it lies in a nut-shell. If you won't do it, I can't swim; and if I can't swim, you sink—every mother's son of you. Oh, come, come—give me a bit of a push at this pinch."

"That's what you've said so often"–

"Fait, an' what if I have? And look at the shoves that I've given you," said Mr. O'Gibbet, with sufficient sternness.

"But a—a—really we shall be found out! The House suspects already that you and we"–

"Bah! bother! hubbabo! Propose you it; I get up and oppose it—vehemently, do you mind—an' the blackguards opposite will carry it for you, out of love for me, ah, ha!—Aisy, aisy—softly say I! Isn't that the way to get along?" and Mr. O'Gibbet winked his eye.

Mr. Flummery, however, looked unhappy, and remained silent and irresolute.

"Oh, my dear sir—exporrige frontem! Get along wid you, you know it's for your own good," said Mr. O'Gibbet; and shoving him on good-humoredly, left the lobby, while Mr. Flummery passed on, with a forced smile, to his seat. He continued comparatively silent, and very wretched, the whole night.

Two hours before the House broke up, but not till after Lord Bulfinch had withdrawn, Mr. Flummery, seizing his opportunity, got up to do the bidding, and eventually fulfilled the prophecy, of Mr. O'Gibbet, amid bitter and incessant jeers and laughter from the opposition.

"Another such victory and we're undone," said Mr. Flummery, with a furious whisper, soon afterwards to Mr. O'Gibbet.

"Och, go to the ould divil wid ye!" replied Mr. O'Gibbet, thrusting his tongue into his cheek, and moving off.

Now Titmouse had contrived to overhear almost every word of the above curious colloquy, and had naturally formed a prodigious estimate of Mr. O'Gibbet, and his influence in the highest quarters.—But to proceed.—Within a few minutes' time might have been seen Titmouse and O'Gibbet earnestly conversing together, remote from observation, in one of the passages leading from the lobby. Mr. O'Gibbet spoke all the while in a tone which at once solicited and commanded attention. "Sir, of course you know you've not a ghost of a chance of keeping your seat? I've heard all about it. You'll be beat, sir,—dead beat; will never be able to sit in this Parlimint, sir, for your own borough, and be liable to no end o' penalties for bribery, besides. Oh, my dear sir, how I wish I had been at your elbow! This would never have happened!"

"Oh, sir! 'pon my soul—I—I"—stammered Titmouse, quite thunderstruck at Mr. O'Gibbet's words.

"Hush—st—hush, wid your chattering tongue, sir, or we'll be overheard, and you'll be ruined," interrupted Mr. O'Gibbet, looking suspiciously around.

"I—I—beg your pardon, sir, but I'll give up my seat. I'm most uncommon sorry that ever—curse me if I care about being a mem"–

"Oh! and is that the way you spake of being a mimber o' Parlimint? For shame, for shame, not to feel the glory of your position, sir! There's millions o' gintlemen envying you, just now!—Sir, I see that you're likely to cut a figure in the House."

"But, begging your pardon, sir, if it costs such a precious long figure—why, I've come down some four or five thousand pounds already," quoth Titmouse, twisting his hand into his hair.

"An' what if ye have? What's that to a gintleman o' your consequence in the country? It's, moreover, only once and for all; only stick in now—and you stay in for seven years, and come in for nothing next general election; and now—d'ye hear me, sir? for time presses—retire, and give the seat to a Tory if you will—(what's the name o' the blackguard? Oh, it's young Delamere)—and have your own borough stink under your nose all your days! But can you keep a secret like a gintleman? Judging from your appearance, I should say yes—sir—is it so?" Titmouse placed his hand over his beating heart, and with a great oath solemnly declared that he would be "mum as death;" on which Mr. O'Gibbet lowered his tone to a faint whisper—"You'll distinctly understand I've nothing to do with it personally, but it's impossible, sir—d'ye hear?—to fight the divil except with his own weapons—and there are too many o' the enemies o' the people in the House—a little money, sir—eh? Aisy, aisy—softly say I! Isn't that the way to get along?" added Mr. O'Gibbet, with a rich leer, and poking Titmouse in the ribs.

"'Pon my life that'll do—and—and—what's the figure, sir?"

"Sir, as you're a young mimber, and of Liberal principles," continued Mr. O'Gibbet, dropping his tone still lower, "three thousand pounds"–Titmouse started as if he had been shot. "Mind, that clears you, sir, d'ye understand? Everything! Out and out, no reservation at all at all—divil a bit!"

"'Pon my precious soul, I shall be ruined between you all!" gasped Titmouse, faintly.

"Sir, you're not the man I took you for," replied Mr. O'Gibbet, impatiently and contemptuously. "Don't you see a barleycorn before your nose? You'll be beat after spending three times the money I name, and be liable to ten thousand pounds' penalties besides for bribery"–

"Oh, 'pon my life, sir, as for that," said Titmouse, briskly, but feeling sick at heart, "I've no more to do with it than—my tiger"–

"Bah! you're a babby, I see!" quoth O'Gibbet, testily. "What's the name o' your man o' business?—there's not a minute to lose—it's your greatest friend I mane to be, I assure ye—tut, what's his name?"

"Mr. Gammon," replied Titmouse, anxiously.

"Let him, sir, be with me at my house in Ruffian Row by nine to-morrow morning to a minute—and alone," said Mr. O'Gibbet, with his lip close to Titmouse's ear—"and once more, d'ye hear, sir?—a breath about this to any one, an' you're a ruined man—you're in my power most complately!"—With this Mr. O'Gibbet and Mr. Titmouse parted—the former having much other similar business on hand, and the latter determined to hurry off to Mr. Gammon forthwith: and in fact he was within the next five minutes in his cab, on his way to Thavies' Inn.

Mr. Gammon was at Mr. O'Gibbet's (of whom he spoke to Titmouse in the most earnest and unqualified terms of admiration) at the appointed time: and after an hour's private conference with him, they both went off to Mr. Flummery's official residence in Pillory Place; but what passed there I never have been able to ascertain with sufficient accuracy to warrant me in laying it before the reader.

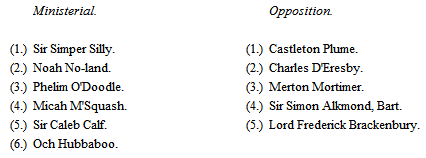

When the day for taking into consideration the Yatton Petition had arrived—on a voice calling out at the door of the House, "Counsel in the Yatton petition!" in walked forthwith eight learned gentlemen, four being of counsel for the petitioner, and four for the sitting member—attended by their respective agents, who stood behind, while the counsel took their seats at the bar of a very crowded and excited House; for there were several election committees to be balloted for on that day. The door was then locked; and the order of the day was read. Titmouse might have been seen popping up and down about the back ministerial benches, like a parched pea. On the front Treasury bench sat Mr. O'Gibbet, his hat slouched over his fat face, his arms folded. On the table stood several glasses, containing little rolls of paper, each about two or three inches long, and with the name of every member of the House severally inscribed on them. These glasses being placed before the Speaker, the clerk rose, and taking out one or two of the rolls of paper at a time, presented them to the Speaker; who, opening each, read out aloud the name inscribed, to the House. Now, the object was, on such occasions, to draw out the names of thirty-three members then present; which were afterwards to be reduced, by each party alternately striking off eleven names, to ELEVEN—who constituted the committee charged with the trial of the petition. Now the astute reader will see that, imagining the House to be divided into two great classes, viz. those favorable and those opposed to the petitioner—according to whose success or failure a vote was retained, lost, or gained to the party—and as the number of thirty-three cannot be more nearly divided than into seventeen and sixteen, 't is said by those experienced in such matters, that in cases where it ran so close—that side invariably and necessarily won who drew the seventeenth name; seeing that each party having eleven names of those in his opponent's interest, to expunge out of the thirty-three, he who luckily drew this prize of the SEVENTEENTH MAN, was sure to have SIX good men and true on the committee against the other's FIVE. And thus of course it was, in the case of a greater or less proportion of favorable or adverse persons answering to their names. So keenly was all this felt and appreciated by the whole House on these interesting—these solemn, these deliberative, and JUDICIAL occasions—that on every name being called, there were sounds heard, and symptoms witnessed, indicative of eager delight or intense vexation. Now, on the present occasion, it would at first have appeared as if some unfair advantage had been secured by the opposition; since five of their names were called, to two of those of their opponents; but then only one of the five answered, (it so happening that the other four were absent, disqualified as being petitioned against, or exempt,) while both of the two answered!—You should have seen the chagrined faces, and heard the loud acclamations of "Ts!—ts!—ts!" on either side of the House, when their own men's names were thus abortively called over!—the delight visible on the other side!—The issue long hung in suspense; and at length the scales were evenly poised, and the House was in a state of exquisite anxiety; for the next eligible name answered to, would really determine which side was to gain or lose a seat.

"Sir Ezekiel Tuddington"—cried the Speaker, amid profound and agitated silence. He was one of the opposition—but answered not; he was absent. "Ts! ts! ts!" cried the opposition.

"Gabriel Grubb"—This was a ministerial man, who rose, and said he was serving on another committee. "Ts! ts! ts!" cried the ministerial side.

"Bennet Barleycorn"—(opposition)—petitioned against. "Ts! ts! ts!" vehemently cried out the opposition.

"Phelim O'Doodle"–

"Here!" exclaimed that honorable member, spreading triumph over the ministerial, and dismay over the opposition side of the House; and the thirty-three names having been thus called and answered to, a loud buzz arose on all sides—of congratulation or despondency.

The fate of the petition, it was said, was already as good as decided.—The parties having retired to "strike"3 the committee, returned in about an hour's time, and the following members were then sworn in, and ordered to meet the next morning at eleven o'clock:—

And the six, of course, on their meeting, chose the chairman, who was a sure card—to wit, Sir Caleb Calf, Bart.4

Mr. Delamere's counsel and agents, together with Mr. Delamere himself, met at consultation that evening, all with the depressed air of men who are proceeding with any undertaking contra spem. "Well, what think you of our committee?" inquired, with a significant smile, Mr. Berrington, the eloquent, acute, and experienced leading counsel. All present shrugged their shoulders, but at length agreed that even with such a committee, their case was an overpowering one; that no committee could dare to shut their eyes to such an array of facts as were here collected; the clearest case of agency made out—Mr. Berrington declared—that he had ever known in all his practice; and eleven distinct cases of BRIBERY, supported each by at least three unexceptionable witnesses; together with half-a-dozen cases of TREATING; in fact, the whole affair, it was admitted, had been most admirably got up, under the management of Mr. Crafty, (who was present,) and they must succeed.

"Of course, they'll call for proof of AGENCY first," quoth Mr. Berrington, carelessly glancing over his enormous brief; "and we'll at once fix this—what's his name—the Unitarian parson, Muff—Muffin—eh?"

"Mudflint—Smirk Mudflint"–

"Aha!—Well!—we'll begin with him, and–then trot out Bloodsuck and Centipede. Fix them—the rest all follow, and they'll strike, in spite of their committee—or—egad—we'll have a shot at the sitting member himself."

By eleven o'clock the next morning the committee and the parties were in attendance—the room quite crowded—such a quantity of Yatton faces!—There, near the chairman, with his hat perched as usual on his bushy hair, and dressed in his ordinarily extravagant and absurd style—his glass screwed into his eye, and his hands stuck into his hinder coat-pockets, and resting on his hips, stood Mr. Titmouse; and after the usual preliminaries had been gone through, up rose Mr. Berrington with the calm confident air of a man going to open a winning case—and an overwhelming one he did open—the chairman glancing gloomily at the five ministerials on his right, and then inquisitively at the five opposition members on his left. The statement of Mr. Berrington was luminous and powerful. As he went on, he disclosed almost as minute and accurate a knowledge of the movements of the Yellows at Yatton, as Mr. Gammon himself could have supplied him with. That gentleman shared in the dismay felt around him. 'T was clear that there had been infernal treachery; that they were all ruined. "By Jove! there's no standing up against this—in spite of our committee—unless we break them down at the agency—for Berrington don't overstate his cases," whispered Mr. Granville, the leading counsel for the sitting member, to one of his juniors, and to Gammon; who sighed and said nothing. With all his experience in the general business of his profession, he knew, when he said this, little or nothing of what might be expected from a favorable election committee. Stronger and stronger, blacker and blacker, closer and closer, came out the petitioner's case. The five opposition members paid profound attention to Mr. Berrington, and took notes; while, as for the ministerials, one was engaged with his betting book, another writing out franks, (in which he dealt,) a third conning over an attorney's letter, and two were quietly playing together at "Tit-tat-to." As was expected, the committee called peremptorily for proof of Agency; and I will say only, that if Smirk Mudflint, Barnabas Bloodsuck, and Seth Centipede, were not fixed as the "Agents" of the sitting member—then there is no such relation as that of principal and agent in rerum naturâ; there never was in this world an agent who had a principal, or a principal who had an agent.—Take only, for instance, the case of Mudflint. He was proved to have been from first to last an active member of Mr. Titmouse's committee; attending daily, hourly, and on hundreds of occasions, in the presence of Mr. Titmouse—canvassing with him—consulting him—making appointments with him for calling on voters, which appointments he invariably kept; letters in his handwriting relating to the election, signed some by Mr. Titmouse, some by Mr. Gammon; circulars similarly signed, and distributed by Mudflint, and the addresses in his handwriting; several election bills paid by him on account of Mr. Titmouse; directions given by him and observed, as to the bringing up voters to the poll; publicans' bills paid at the committee-room, in the presence of Mr. Titmouse—and, in short, many other such acts as these were established against all three of the above persons. Such a dreadful effect did all this have upon Mr. Bloodsuck and Mr. Centipede, that they were obliged to go out, in order to get a little gin and water; for they were indeed in a sort of death-sweat. As for Mudflint, he seemed to get sallower and sallower every minute; and felt almost disposed to utter an inward prayer, had he thought it would have been of the slightest use. Mr. Berrington's witnesses were fiercely cross-examined, but no material impression was produced upon them; and when Mr. Granville, on behalf of the sitting member, confident and voluble, rose to prove to the committee that his learned friend's case was one of the most trumpery that had ever come before a committee—a mere bottle of smoke;—that the three gentlemen in question had been no more the agents of the sitting member than was he—the counsel then on his legs—the agent of the Speaker of the House of Commons, and that every one of the petitioner's witnesses was unworthy of belief—in fact perjured—how suddenly awake to the importance of the investigation became the ministerialist members! They never removed their eyes from Mr. Granville, except to take notes of his pointed, cogent, unanswerable observations! He called no witnesses. At length he sat down; and strangers were ordered to withdraw—and 'twas well they did: for such an amazing uproar ensued among the committee, as soon as the five opposition members discovered, to their astonishment and disgust, that there was the least doubt among their opponents as to the establishment of agency, as would not, possibly, have tended to raise that committee, as a judicial body, in public estimation. After an hour and a half's absence, strangers were readmitted. Great was the rush—for the fate of the petition hung on the decision to be immediately pronounced. As soon as the counsel had taken their seats, and the eager, excited crowd been subdued into something like silence, the chairman, Sir Caleb Calf, with a flushed face, and a very uneasy expression, read from a sheet of foolscap paper, which he held in his hand, as follows:—