полная версия

полная версияPacking and Portaging

Dillon Wallace

Packing and Portaging

CHAPTER I

PACKING AND THE OUTFIT

ORDINARILY the verb to pack means to stow articles snugly into receptacles, but in the parlance of the trail it often means to carry or transport the articles from place to place. The pack in the language of the trail is the load a man or horse carries.

Likewise, a portage on a canoe route is a break between navigable waters, over which canoe and outfit must be carried; or the word may be used as a verb, and one may say, "I will portage the canoe," meaning "I will carry the canoe." In the course of the following pages these terms will doubtless all be used in their various significations.

Save for the few who are able to employ a retinue of professional guides and packers to attend to the details of transportation, the one chief problem that confronts the wilderness traveler is that of how to reduce the weight of his outfit to the minimum with the least possible sacrifice of comfort. It is only the veriest tenderfoot that deliberately endures hardships or discomforts where hardships and discomforts are unnecessary. Experienced wilderness travelers always make themselves as comfortable as conditions will permit, and there is no reason why one who hits the trail for sport, recreation or health should do otherwise.

In a description, then, of the methods of packing and transporting outfits the tenderfoot and even the man whose feet are becoming calloused may welcome some hints as to the selection of compact, light, but, at the same time, efficient outfits. These hints on outfitting, therefore, I shall give, leaving out of consideration the details of camp making, camp cookery and those phases of woodcraft that have no direct bearing upon the prime question of packing and transportation on the trail.

Let us classify the various methods of wilderness travel under the following heads: 1. By Canoe; 2. With Saddle and Pack Animals; 3. Afoot in Summer; 4. On Snowshoes; 5. With Dogs and Sledge. Taking these in order, and giving our attention first to canoe travel, it will be found convenient further to subdivide this branch of the subject and discuss in order: (a) The Canoe and its Equipment; (b) Camp Equipment for a Canoe Trip; (c) Personal Equipment; (d) Food; (e) The Portage.

CHAPTER II

THE CANOE AND ITS EQUIPMENT

A SIXTEEN-FOOT canoe with a width of at least 33 inches and a depth of at least 12 inches will accommodate two men, an adequate camping outfit and a full ten weeks' provisions very nicely, and at the same time not lie too deep in the water. A fifteen-foot canoe, unless it has a beam of at least 35 inches and a depth of 12 inches or more, is unsuitable. Three men with their outfit and provisions will require an eighteen-foot canoe with a width of 35 inches or more and a depth of no less than 13 inches, or a seventeen-foot canoe with a width of 37 inches and 13 inches deep. The latter size is lighter by from ten to fifteen pounds than the former, while the displacement is about equal.

The best all-around canoe for cruising and hard usage is the canvas-covered cedar canoe. Both ribs and planking should be of cedar, and only full length planks should enter into the construction. Where short planking is used the canoe will sooner or later become hogged—that is, the ends will sag downward from the middle.

In Canada the "Peterborough" canoe is more largely used than the canvas-covered. These are to be had in both basswood and cedar. Cedar is brittle, while basswood is tough, but the latter absorbs water more readily than the former and in time will become more or less waterlogged.

Cruising canoes should be supplied with a middle thwart for convenient portaging. Any canoe larger than sixteen feet should have three thwarts. To lighten weight on the portage, and provide more room for storing outfit, it is advisable to remove the cane seats with which canvas canoes are usually provided. This can be readily done by unscrewing the nuts beneath the gunwale which hold the seats in position.

Good strong paddles—sufficiently strong to withstand the heavy strain to which cruising paddles are put—should be selected. On the portage they must bear the full weight of the canoe; they will frequently be utilized in poling up stream against stiff currents; and in running rapids they will be subjected to rough usage. On extended cruises it is advisable to carry one spare paddle to take the place of one that may be rendered useless.

Experienced canoemen pole up minor rapids. Poles for this purpose can usually be cut at the point where they are needed, but pole "shoes"—that is, spikes fitted with ferrules—to fit on the ends of poles are a necessary adjunct to the outfit where poling is to be done. Without shoes to hold the pole firmly on the bottom of the stream the pole may slip and pitch the canoeman overboard. The ferrules should be punctured with at least two nail holes, by which they may be secured to the poles, and a few nails should be carried for this purpose.

A hundred feet or so of half-inch rope should also be provided, to be used as a tracking line and the various other uses for which rope may be required.

CHAPTER III

CAMP EQUIPMENT FOR A CANOE TRIP

PERSONAL likes and prejudices have much to do with the form of tent chosen. My own preference is for either the "A" or wedge tent, with the Hudson's Bay model as second choice, for general utility. Either of these is particularly adapted also to winter travel where the tent must often be pitched upon the snow. If, however, the tent is only to be used in summer, and particularly in canoe travel where a light, easily erected model is desired, the Frazer tent is both ideal for comfort and is an exceedingly light weight model for portaging.

Duck or drill tents are altogether too heavy and quite out of date. They soak water and are an abomination on the portage. The best tent is one of balloon silk, tanalite, or of extra light green waterproofed tent cloth. The balloon silk tent is very slightly heavier than either of the others, but is exceedingly durable. For instance, a 71/3 × 71/3 foot "A" tent of either tanalite or extra light green waterproof tent cloth, fitted with sod cloth, complete, weighs eight pounds, while a similar tent of waterproof balloon silk weighs nine pounds. A Hudson's Bay model, 6 × 9 feet, weighs respectively seven and seven and one-half pounds.

These three cloths are not only waterproof and practically rot proof, but do not soak water, which is a feature for consideration where much portaging is to be done and camp is moved almost daily.

Some dealers recommend that customers going into a fly or mosquito country have the tent door fitted with bobbinet. The idea is good, but cheese cloth is much cheaper and incomparably better than bobbinet.

The cheese-cloth door should be made rather full, and divided at the center from tent peak to ground, with numerous tie strings to bring the edges tight together when in use, and other strings or tapes on either side, where it is attached to the tent, to reef or roll and tie it back out of the way when not needed.

When purchasing a light-weight tent, see that the dealer supplies a bag of proper size in which to pack it.

A pack cloth 6 × 7 feet in size, of brown waterproof canvas weighing about 31/2 pounds, makes an excellent covering for the tent floor at night. On the portage blankets and odds and ends will be packed and carried on it. If one end and the two sides of the pack cloth are fitted with snap buttons it may be converted into a snug sleeping bag with a pair of blankets folded lengthwise, the bottom and sides of the blanket secured with blanket safety pins as a lining for the bag.

My standby for summer camping is a fine all-wool gray blanket 72 × 78 inches in size and weighing 51/2 pounds. This I have found sufficient even in frosty autumn weather—always, in fact, until the weather grows cold enough to freeze streams and close them to canoe navigation. Used as a lining for the improvised pack cloth sleeping bag, this blanket is quite bedding enough and makes an exceedingly comfortable bed, too.

A three-quarter axe with a 24- or 28-inch handle makes a mighty good camp axe. A full axe is heavy and inconvenient to portage and the lighter axe will serve every purpose in any country at any time. Personally I favor the Hudson's Bay axe. This may be had fitted either with a 24-inch or 18-inch handle. In the two-party outfit which we are discussing there should be two axes, one of which may be fitted with the shorter handle, but the other should have at least a 24- and preferably a 28-inch handle. Every axe should have a leather sheath or scabbard for convenient packing. The so-called pocket axes are too small to be of practical use. The camper does not wish to miss the luxury of the big evening camp-fire, and he can never provide for it with a small hatchet or toy pocket axe.

Cooking utensils of aluminum alloy are the lightest and best for the trail. Tin and iron will rust, enamel ware will chip, and unalloyed aluminum is too soft and bends out of shape. The best sporting goods dealers carry complete outfits of aluminum alloy. I have used them in the frigid North and in the tropics, in canoe, sledging, tramping and horseback journeys, and can recommend them unequivocally, save perhaps the frying pan.

The two-man cooking and dining outfit should contain the following utensils:

1 Pot with cover 7 × 61/2 inches, capacity three quarts.

1 Coffee pot 6 × 61/8 inches, capacity two quarts.

1 Steel frying pan 97/8 × 2 inches, with folding handle.

1 Pan 9 × 3 inches, with folding handle, for mixing- and dish-pan.

2 Plates 87/8 inches diameter.

2 Cups.

2 Aluminum alloy forks.

2 Dessert spoons.

1 Large cooking spoon.

1 Dish mop.

2 Dish towels.

The regular aluminum alloy cup is too small for practical camp use. There is an aluminum bowl, however, holding one pint, but without a handle. This is about the right size for a practical cup, and I have a handle riveted on it and use it as a cup. The top only of the handle should be attached, that the cups may set one inside the other. The heat conducting quality of aluminum makes it a question whether or not enamel cups are not preferable.

To pack the outfit snugly, set the mixing pan into the frying pan, the handles of both pans folded, place the plates, one on top of the other, in the mixing pan, the cooking pot on top of these, and the coffee pot inside the cooking pot. The cups will fit in the coffee pot. The weight of this outfit complete is 51/2 pounds.

A waterproof canvas bag of proper size should be provided in which to pack the utensils. Forks and spoons, wrapped in a dish towel, will fit nicely in the canvas bag alongside the pots.

Waterproof canvas is suggested for the bag, not to protect the utensils but because anything but waterproofed material will absorb moisture and become watersoaked in rainy weather, adding materially to the weight of the outfit.

One of the handiest aids to baking is the aluminum reflecting baker. An aluminum baker 16 × 18 inches when open, folds to a package 12 × 18 inches and about two inches thick, and fitted into a waterproof canvas case weighs, case and all, about four pounds.

Broilers, fire irons, fire blowers or inspirators, as they are sometimes called, and many other things that are convenient enough but quite unnecessary, should never burden the outfit. Even though the weight of some of them may be insignificant, each additional claptrap makes one more thing to look after. There are a thousand and one claptraps, indeed, that outfitters offer, but which do not possess sufficient advantage to pay for the care and labor of transportation, and my advice is, leave them out, one and all.

Outfitters supply small packing bags of proper size to fit, one on top of another, into larger waterproof canvas bags. These small bags are made preferably of balloon silk. By using them the whole outfit may be snugly and safely packed for the portage.

In one of these small bags keep the general supply of matches, though each canoeist should carry a separate supply for emergency in his individual kit.

In like manner two or three cakes of soap should be packed in another small bag. Floating soap is less likely to be lost than soap that sinks.

A dozen candles will be quite enough. These if packed in a tin box of proper size will not be broken.

Repair kits should be provided. A file for sharpening axes and a whetstone for general use are of the first importance. Include also a pair of pincers, a ball of stout twine and a few feet of copper wire. A tool haft or handle with a variety of small tools inside is convenient. Either a stick of canoe cement, a small supply of marine glue, or a canoe repair outfit such as canoe manufacturers put up and which contain canvas, white lead, copper tacks, calor and varnish will be found a valuable adjunct to the outfit should the canoe become damaged. This tool and repair equipment should be packed in a strong canvas bag small enough to drop into the larger nine-inch waterproof bag.

A small leather medicine case with vials containing, in tabloid form, a cathartic, an astringent (lead and opium pills are good) and bichloride of mercury, suffices for the drug supply. Surgical necessities are: Some antiseptic bandages, a package of linen gauze, a spool of adhesive plaster and one-eighth pound of absorbent cotton, wrapped in oiled silk. In addition most campers find it convenient to have in their personal outfit a pair of small scissors. These are absolutely necessary if one is to put on a bandage properly. The regular surgical scissors, the two blades of which hook together at the center, are the most convenient sort, both to use and to carry, and have the keenest edge.

A pair of tweezers takes up but little room and is useful for extracting splinters or for holding a wad of absorbent cotton in swabbing out a wound, as cotton will, of course, become septic if held in the fingers.

A small scalpel is better than the knife blade for opening up an infection, as it is more convenient to handle and will make a deep short incision when desired. These will all be packed in one of the small balloon silk bags.

CHAPTER IV

PERSONAL EQUIPMENT

EACH canoeist should have a personal kit or duffle bag of waterproof canvas. These may be purchased from outfitters and are usually 36 inches deep and of 12, 15, 18 or 21 inches diameter. The 12-inch bag, however, is amply large to accommodate all one needs in the way of clothing and other personal gear. This, as well as every other waterproof canvas packing bag mentioned, excepting the cooking kit bag, should be supplied with a handle on the bottom and one on the side. These bags not only keep the contents dry, but, as previously stated, do not absorb moisture to add to the weight, a very essential feature where every unnecessary pound must be eliminated. I was once capsized in a rapid and my duffle bag lay half a day in the water before it was recovered. The contents were perfectly dry.

One suit of medium weight woolen underclothing in addition to the suit worn is ample for a short trip. Four extra pairs of thick woolen socks should be provided—the home-knit kind. An excellent material for trousers to be worn on the trail is moleskin, though for midsummer wear a good quality khaki is first rate. Moleskin, however, will withstand the hardest usage and to my mind is superior to khaki or any other material where wading is necessary and on cold or rainy days, as it is very nearly windproof. A good leather belt should be worn, even though suspenders support the trousers.

The outer shirt should be of light weight gray or brown flannel and provided with pockets. A blue flannel shirt of the best quality is all right. The cheaper qualities of blue crock, and this feature makes them objectionable. If the outer shirt is too heavy it will be found cumbersome under the exertion of the portage.

A large, roomy Pontiac shirt to slip over the outer shirt and use as a sweater is much preferable to a sweater on the trail. It is windproof and warm. Do not take a coat—the Pontiac shirt will be both coat and sweater. A coat is always in the way on a canoe trip and makes the pack that much heavier.

A pair of low leather or canvas wading shoes for river work and larrigans or shoe pacs for ordinary wear, large enough to admit two pairs of woolen socks, are best suited to canoeing. Heavy, hobnailed mountaineer shoes or boots are not in place here.

Heavy German socks, supplied with garter and clasp to hold them in position, are better than canvas leggings, and protect the legs from chill at times when wading is necessary in icy waters.

Any kind of an old slouch hat is suitable.

Some canoeists take with them a suit of featherweight oilskin. Personally I have never worn rainproof garments when canoeing. Once I carried a so-called waterproof coat, but it was not waterproof. It leaked water like a sieve, and was no protection even from the gentlest shower. I am inclined, however, to favor featherweight oilskins, though not while portaging—they would be found too warm—but when paddling in rainy weather, or to wear on rainy days about camp.

If the trip is to extend into a black fly or mosquito region, protection against the insects should be provided. A head net of black bobbinet that will set down upon the shoulders, with strings to tie under the arms, is about the best arrangement for the head. Old loose kid gloves, with the fingers cut off, and farmers' satin elbow sleeves to fit under the wrist bands of the outer shirt will protect the wrists and hands. The armlets should be well and tightly sewn upon the gloves, for black flies are not content to attack where they alight, and will explore for the slightest opening and discover some undefended spot. They are, too, a hundred times more vicious than mosquitoes.

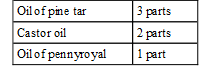

There are many receipts for fly dope, but in a half hour after application perspiration will eliminate the virtue of most mixtures and a renewed application must be made. Nessmuk's receipt is perhaps as good as any, and the formula is as follows:

If when you were a child your father held your nose as an inducement for you to open your mouth while your mother poured castor oil down your throat, the odor of the castor oil rising above the odors of the other ingredients will revive sad memories. Indeed it is claimed for this mixture that the dead will rise and flee from its compounded odor as they would flee from eternal torment. It certainly should ward off such little creatures as black flies and mosquitoes.

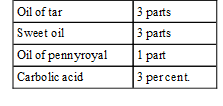

Another effective mixture is:

An Indian advised me once to carry a fat salt pork rind in my pocket, and now and again rub the greasy side upon face and hands. I tried it and found it nearly as good as the dopes.

Unless one penetrates, however, far north In Canada during black fly season these extraordinary precautions will scarcely be necessary. There Is nowhere In the United States a region where black flies are really very bad (though perhaps I am drawing invidious comparisons in making the statement), and even in interior Newfoundland they are, compared with the farther north, tame and rather inoffensive though always troublesome.

The choice of fishing tackle, guns and arms depends largely upon personal taste. Steel rods of the best quality will serve better than split bamboo on an extended trip where one, continuously on the portage trail, is often unable to properly dry the tackle. The steady soaking of a split bamboo rod for a week is likely to loosen the sections and injure a fine rod. A waterproof canvas or pantasote case is the right sort for the rod—leather cases are unpractical on a cruising trip.

Leather gun cases, too, under like circumstances will become watersoaked, and under any circumstances they are unnecessarily heavy. Use canvas cases therefore in consideration for your back. They are light and in a season of rain immeasurably better than leather.

Economize, also, on ammunition. Do your target practice before you hit the trail. A hunter that cannot get his limit of big game with twenty rifle cartridges is an unsafe individual to turn loose in the woods.

For spruce grouse, ptarmigan and other small game a ten-inch barrel, 22-caliber single-shot pistol is an excellent arm, provided one has had some previous experience in its use. It is not a burden on the belt, and a handful of cartridges in the pocket are not noticed.

Pack your cartridges in a strong canvas bag, your gun grease and accessories in another receptacle.

On the belt also carry a broad-pointed four-inch blade skinning knife of the ordinary butcher knife shape. This will be your table knife, as well as cooking and general utility knife.

In the pocket carry a stout jackknife, a waterproof matchbox, always kept well filled, and a compass.

A film camera is more practical for the trail than a plate camera for many reasons, one of which is weight. Plates are heavy and easily broken. It is well to have each roll of films put up separately in a sealed, water-tight tin. Dealers will supply them thus at five cents extra for each film roll. A waterproof pantasote case, too, is better than leather, for leather in a long-continued rain will become watersoaked, as before stated.

If a plate camera is carried the plates may be packed in a small light wooden box—a starch box, for instance. The box will protect them under ordinary circumstances. Film rolls, however, may be carried in a small canvas bag that will slip into one of the larger waterproof bags.

My object in outlining outfit is rather to emphasize the possibilities of selecting a light and efficient outfit that may be easily packed and transported on the trail, than to evolve an infallible check list; therefore I shall not attempt to name in detail toilet articles, tobacco and odds and ends. Take nothing, however, save those things you will surely find occasion to use, unless I may suggest an extra pipe, should your pipe be lost. A small balloon silk bag will hold them, together with a sewing case containing needles, thread, patches and some safety pins. Another will hold the hand towels and hand soap in daily use, while an extra hand towel may be stowed in your duffle bag.

In concluding this chapter it may be pertinent to say that the novice on the trail is pretty certain to burden himself with many things he will seldom or never use. Take your outfitter into your confidence. Tell him what sort of a trip you contemplate and he will advise you. First-class outfitters are usually practical out-of-door men and camping experts. They have made an extended study of the subject, for it is part of their business to do so. Therefore, in selecting outfit, it is both safe and wise to rely upon the advice of any responsible outfitter.

CHAPTER V

FOOD

THE true wilderness voyager is willing to endure some discomforts on the trail, to work hard and submit to black flies and other pests, but as a reward he usually demands satisfying meals. There is, indeed, no reason for him to deny himself a variety and a plenty, unless his trip is to extend into months. Weight on the portage trail is always the consideration that cuts down the ration. Packing on one's back a ration to be used two or three months hence is discouraging.

I have evolved a two-week food supply for two men, based upon the United States army ration, varied as the result of my own experiences have dictated. It offers not only great variety, but is an exceedingly bountiful ration even for hungry men. Personal taste will suggest some eliminations or substitutions that may be made without material loss or change in weight. If there is certainty of catching fish or killing game, or if opportunity offers for purchasing fresh supplies along the trail, reductions in quantity may be made accordingly. For each additional man, or for any period beyond two weeks, a proportionate increase in quantity may be made.