полная версия

полная версияTravels on the Amazon

It is a fact which has been frequently stated, and which seems fully established, that the Amazon carries its fresh waters out into the ocean, which it discolours for a distance of a hundred and fifty miles from its mouth. It is also generally stated that the tide flows up the river as far as Obidos, five hundred miles from the mouth. These two statements appear irreconcilable, for it is not easy to understand how the tides can flow up to such a great distance, and yet no salt water enter the river. But the fact appears to be, that the tide never does flow up the river at all. The water of the Amazon rises, but during the flood as well as the ebb the current is running rapidly down. This takes place even at the very mouth of the river, for at the island of Mexiana, exposed to the open sea, the water is always quite fresh, and is used for drinking all the year round. But as salt water is heavier than fresh, it might flow up at the bottom, while the river continued to pour down above it; though it is difficult to conceive how this could take place to any extent without some salt water appearing at the margins.

The rising of the water so far up the river can easily be explained, and goes to prove also that the slope of the river up to where the tide has any influence cannot be great; for as the waters of the ocean rose, the river would of course be banked up, the velocity of its current still forcing its waters onward; but it is not easy to see how the stream could be thus elevated to a higher level than the waters of the ocean which caused the rise, and we should therefore suppose that at Obidos, where the tidal rise ceases to be felt, the river is just higher than the surface of the ocean at the highest spring-tides.

A somewhat similar phenomenon is seen at the mouth of the Tapajóz. Here, at the end of the dry season, there is but a small body of water, and the current is very sluggish. The Amazon, however, rises considerably with the tides, and its waters then become higher than those of the Tapajóz, and they therefore enter into that river and force it back; we then see the Amazon flowing rapidly down, at the same time that the Tapajóz is flowing up.

It seems to be still a disputed question among geographers, whether the Pará river is or is not a branch of the Amazon. From my own observation, I am decidedly of opinion that it is not: it appears to me to be merely the outlet of the Tocantíns and of numerous other small streams. The canal or channel of Tagipurú, which connects it with the Amazon, and by which all the trade between Pará and the interior is carried on, is one of a complete network of channels, along which the tide ebbs and flows, so as in a great measure to disguise the true direction and velocity of its current. It seems probable that not a drop of Amazon water finds its way by this channel into the Pará river, and I ground my opinion upon the following facts.

It is well known, that in a tidal river the ebb-tide will continue longer than the flood, because the stream of the river requires to be overcome, and thus delays the commencement of the flood, while it facilitates that of the ebb. This is very remarkable in all the smaller rivers about Pará. Taking this as our guide, we shall be able to ascertain which way the current in the Tagipurú sets, independently of the tide.

On my journey from Pará to the Amazon, our canoe could only proceed with the tide, having to wait moored to the bank while it was against us, so that we were of course anxious to find the time of our tedious stoppages diminished. Up to a certain point, we always had to wait more time than we were moving, showing that the current set against us and towards Pará; but after passing that point, where there was a bend, and several streams met, we had but a short time to wait, and a long ebb in our favour, showing that the current was with us or towards the Amazon, whereas it would evidently have been different had there been any permanent current flowing from the Amazon through the Tagipurú towards Pará.

I therefore look upon the Tagipurú as a channel formed by the small streams between the Tocantíns and Xingú, meeting together about Melgáco, and flowing through a low swampy country in two directions, towards the Amazon, and towards the Pará river.

At high tides the water becomes brackish, even up to the city of Pará, and a few miles down is quite salt. The tide flows very rapidly past Pará, up all the adjacent streams, and as far as the middle of the Tagipurú channel; another proof that a very small portion, if any, of the Amazon water is there to oppose it.

The curious phenomenon of the bore, or "piroróco," in the rivers Guamá and Mojú, I have described and endeavoured to explain in my Journal, and need not now repeat the account of it. (See page 89.)

Our knowledge of the courses of most of the tributaries of the Amazon is very imperfect. The main stream is tolerably well laid down in the maps as far as regards its general course and the most important bends; the details, however, are very incorrect. The numerous islands and parallel channels,—the great lakes and offsets,—the deep bays,—and the varying widths of the stream, are quite unknown. Even the French survey from Pará to Obidos, the only one which can lay claim to detailed accuracy, gives no idea of the river, because only one channel is laid down. I obtained at Santarem a manuscript map of the lower part of the river, much more correct than any other I have seen. It was, with most of my other papers, lost on my voyage home; but I hope to be able to obtain another copy from the same party. The Madeira and the Rio Negro are the only other branches of the Amazon whose courses are at all accurately known, and the maps of them are very deficient in anything like detail. The other great rivers, the Xingu, the Tapajóz, the Purús, Coarí, Teffe, Juruá, Jutaí, Jabarí, Içá, Japurá, etc., though all inserted in our maps, are put in quite by guess, or from the vaguest information of the general direction of their course. Between the Tocantíns and the Madeira, and between the Madeira and the Uaycali, there are two tracts of country of five hundred thousand square miles each, or each twice as large as France, and as completely unexplored as the interior of Africa.

The Rio Negro is one of the most unknown in its characteristic features; although, as before stated, its general course is laid down with tolerable accuracy. I have narrated in my Journal how I was prevented from descending on the north side of it, and thus completing my survey of its course.

The most remarkable feature is the enormous width to which it spreads,—first, between Barra and the mouth of the Rio Branco, and from thence to near St. Isabel. In some places, I am convinced, it is between twenty and thirty miles wide, and, for a very great distance, fifteen to twenty. The sources of the rivers Uaupés, Isanna, Xié, Rio Negro, and Guaviare, are very incorrectly laid down. The Serra Tunuhy is generally represented as a chain of hills cutting off these rivers; it is, however, a group of isolated granite peaks, about two thousand feet high, situated on the north bank of the river Isanna, in about 1° north latitude and 70° west longitude. The river rises considerably beyond them, in a flat forest-country, and further west than the Rio Negro, for there is a path across to the Inirizá, a branch of the Guaviare which does not traverse any stream, so that the Rio Negro does not there exist.

My own journey up the Uaupés extended to near 72° west longitude. Five days further in a small canoe, or about a hundred miles, is the Jurupari caxoeira, the last fall on the river. Above that, traders have been twelve days' journey on a still, almost currentless river, which, by the colour of its water, and the aspect of its vegetation, resembles the Upper Amazon. For all this distance, which must reach very nearly to the base of the Andes, the river flows through virgin forest. But the Indians in the upper part say there are campos, or plains, and cattle, further up; and they possess Spanish knives and other articles, showing that they have communications with the civilised inhabitants of the country to the east of Bogotá.

I am therefore strongly inclined to believe that the rivers Ariarí and others, rising about a hundred miles south of Bogotá, are not, as shown in all our maps, the sources of the Guaviare, but of the Uaupés, and that the basin of the Amazon must therefore be here extended to within sixty miles of the city of Bogotá. This opinion is strengthened by information obtained from the Indians of Javíta, who annually ascend the Guaviare to fish in the dry season, and who state that the river is very small, and in its upper part, where some hills occur and the forest ends, it is not more than a hundred yards wide; whereas the Uaupés, at the furthest point the traders have reached, is still a large river, from a quarter of a mile to a mile in width.

The Amazon and all its branches are subject, like most tropical rivers, to an annual rise and fall of great regularity. In the main stream, and in all the branches which flow from the Andes, the waters begin to rise in December or January, when the rains generally commence, and continue rising till June, when the fine weather has just set in. The time when the waters begin to fall is about the 21st of June,—seldom deviating more than a few days from this date. In branches which have their sources in a different direction, such as the Rio Negro, the time of rising does not coincide. On that river the rains do not commence steadily till February or March, when the river rises with very great rapidity, and generally is quite filled by June, and then begins to fall with the Amazon. It thus happens that in the months of January and February, when the Amazon is rising rapidly, the Rio Negro is still falling in its upper part; the waters of the Amazon therefore flow into the mouth of the Rio Negro, causing that river to remain stagnant like a lake, or even occasionally to flow back towards its source. The total rise of the Amazon between high and low water mark has not been accurately ascertained, as it cannot be properly determined without a spirit-level; it is, however, certainly not less than forty, and probably often fifty feet. If therefore we consider the enormous water surface raised fifty feet annually, we shall gain from another point of view an idea of the immense quantity of water falling annually in the Amazon valley. We cannot take the length of the Amazon with its main tributaries at less than ten thousand miles, and their average width about two miles; so that there will be a surface of twenty thousand square miles of water, raised fifty feet every year. But it is not only this surface that is raised, for a great extent of land on the banks of all the rivers is flooded to a great depth at every time of high water. These flooded lands are called, in the language of the country, "gapó" and are one of the most singular features of the Amazon. Sometimes on one side, sometimes on both, to a distance of twenty or thirty miles from the main river, these gapós extend on the Amazon, and on portions of all its great branches. They are all covered with a dense virgin forest of lofty trees, whose stems are every year, during six months, from ten to forty feet under water. In this flooded forest the Indians have paths for their canoes, cutting across from one river to another, which are much used, to avoid the strong current of the main stream. From the mouth of the river Tapajoz to Coary, on the Solimões, a canoe can pass, without once entering the Amazon: the path lies across lakes, and among narrow inland channels, and through miles of dense flooded forest, crossing the Madeira, the Purus, and a hundred other smaller streams. All along, from the mouth of the Rio Negro to the mouth of the Iça, is an immense extent of gapó, and it reaches also far up into the interior; for even near the sources of the Rio Negro, and on the upper waters of the Uaupés, are extensive tracts of land which are annually overflowed.

In the whole country around the mouth of the Amazon, round the great island of Marajó, and about the mouths of the Tocantíns and Xingú, the diurnal and semi-monthly tides are most felt, the annual rise and fall being almost lost. Here the low lands are overflowed at all the spring-tides, or every fortnight, subjecting all vegetation to another peculiar set of circumstances. Considerable tracts of land, still covered with vegetation, are so low, that they are flooded at every high water, and again vary the conditions of vegetable growth.

GEOLOGY

Fully to elucidate the Geology of the Amazon valley, requires much more time and research than I was able to devote to it. The area is so vast, and the whole country being covered with forests renders natural sections so comparatively scarce, that the few distant observations one person can make will lead to no definite conclusions.

It is remarkable that I was never able to find any fossil remains whatever,—not even a shell, or a fragment of fossil wood, or anything that could lead to a conjecture as to the state in which the valley existed at any former period. We are thus unable to assign the geological age to which any of the various beds of rock belong.4

My notes, and a fine series of specimens of the rocks of the Rio Negro, were lost, and I have therefore very few materials to go upon.

Granite seems to be, in South America, more extensively developed than in any other part of the world. Darwin and Gardner found it in every part of the interior of Brazil, in La Plata, and Chile. Up the Xingú Prince Adalbert met with it. Over the whole of Venezuela and New Granada, it was found by Humboldt. It seems to form all the mountains in the interior of Guiana, and it was met with by myself over the whole of the upper part of the Rio Negro, and far up the Uaupés towards the Andes.

From what I could see of the granitic formation of the Upper Rio Negro, it appeared to be spread out in immense undulating areas, the hollows of which, being filled up with alluvial deposits, form those beds of earth and clay which occur, of various dimensions, everywhere in the midst of the granite formation. In these places grow the lofty virgin forests, while on the scantily covered granite rocks, and where beds of sand occur, are the more open catinga forests, so different in their aspect and peculiar in their vegetation. What strikes one most in this great formation, is its almost perfect flatness. There are no ranges of mountains, or even slightly elevated plateaus; all is level, except the abrupt peaks that rise suddenly from the plain, to a height of from one hundred to three thousand feet. In the Upper Rio Negro these peaks are very numerous. The first is the Serra de Jacamí, a little above St. Isabel; it rises immediately from the bank of the river, on the south side, to a height of about six hundred feet. Several others are scattered about, but the Serras de Curicuriarí are the most lofty. They consist of a group of three or four mountains, rising abruptly to the height of near three thousand feet; towards their summits are immense precipices and jagged peaks. Higher up, on the same river, is another group of rather less height. On the Uaupés are numerous hills, some conical, others dome-shaped, but all keeping the same character of abrupt elevations, quite independent of the general profile of the country. About the falls of the river Uaupés there are small hills of granite, broken about in the greatest confusion. Great chasms or bowls occur, and slender pillars of rock rise above the surrounding forest like dead trunks of giant trees. Up the river Isanna, the Tunuhy mountains are a similar isolated group. The Cocof is a quadrangular or cubical mass, about a thousand feet in elevation, which forms the boundary between Brazil and Venezuela; and behind it are the Pirapocó, and the serras of the Cababurís, which seem rather more extensive, and form something more like a connected range of hills.

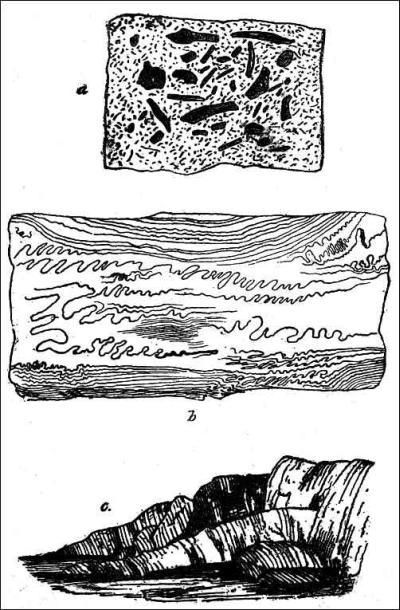

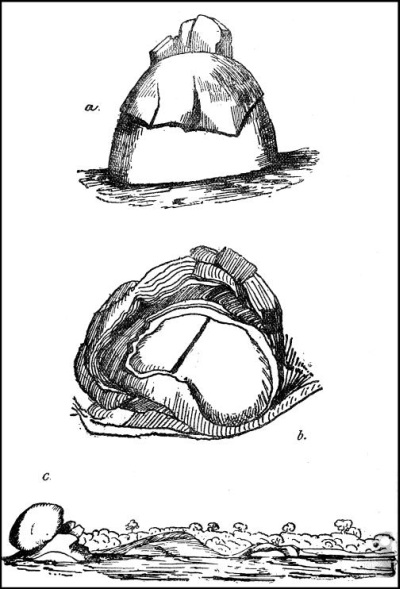

PLATE II.

a. Fragments embedded in granite. b. Granite with twisted veins. c. Stratified rocks protruded through granite.

GRANITE ROCKS AND VEINS, ETC.

PLATE III.

FORMS OF GRANITE ROCKS.

But the great peculiarity of them all is, that the country, does not perceptibly rise to their bases; they spring up abruptly, as if elevated by some local isolated force. I ascended one of the smaller of these serras as far as practicable, and have recorded my impressions of it in my Journal. (See page 153.)

The isolation and abrupt protrusion of these mountains is not, however, altogether without parallel in the Andes itself. This mighty range, from all the information I can obtain, rises with almost equal abruptness from an apparently level plain. The Andes of Quito, and southward to the Amazon, is like a huge rocky rampart, bounding the great plain which extends in one unbroken imperceptible slope from the Atlantic Ocean to its base. It is one of the grandest physical features of the earth,—this vast unbroken plain,—that mighty and precipitous mountain-range.

The granitic rocks of the Rio Negro in general contain very little mica; in some places, however, that mineral is abundant, and exists in large plates. Veins of pure quartz are common, some of very great size; and numerous veins or dykes of granite, of a different colour or texture. The direction of these is generally nearer east and west, than north and south.

Just below the falls of the Rio Negro are some coarse sandstone rocks, apparently protruding through the granite, dipping at an angle of 60° or 70° south-south-west. (Plate II. c.) Near the same place a large slab of granite rock exhibits quantities of curiously twisted or folded quartz veins (Plate II. b.), which vary in size from a line to some inches in diameter, and are folded in a most minute and regular manner.

On an island in the river, near this place, are finely stratified crystalline rocks, dipping south from 70° to vertical, and sometimes waved and twisted.

The granite often exhibits a concentric arrangement of laminæ, particularly in the large dome-shaped masses in the bed of the river (Plate III. a, c), or in portions protruding from the ground (Plate III. b). Near São Gabriel, and in the Uaupés, large masses of pure quartz rock occur, and the shining white precipices of the serras are owing, I have no doubt, to the same cause. At Pimichin, near the source of the Rio Negro, the granite contains numerous fragments of stratified sandstone rock imbedded in it (Plate II. a); I did not notice this so distinctly at any other locality.

High up the river Uaupés there is a very curious formation. All along the river-banks there are irregular fragments of rocks, with their interstices filled up with a substance that looks exactly like pitch. On examination, it is found to be a conglomerate of sand, clay, and scoriæ, sometimes very hard, but often rotten and easily breaking to pieces; its position immediately suggests the idea of its having been liquid, for the fragments of rocks appear to have sunk in it.

Coarse volcanic scoriæ, with a vitreous surface, are found over a very wide area. They occur at Caripé, near Pará,—above Baião, in the Tocantíns,—at the mouth of the Tapajóz,—at Villa Nova, on the Amazon,—above Barra, on the Rio Negro, and again up the Uaupés. A small conical hill behind the town of Santarem, at the mouth of the Tapajóz, has all the appearance of being a volcanic cone.

The neighbourhood of Pará consists entirely of a coarse iron sandstone, which is probably a continuation of the rocks observed by Mr. Gardner at Maranham and in the Province of Piauhy, and which he considered to belong to the chalk formation. Up the Tocantíns we found fine crystalline stratified rocks, coarse volcanic conglomerates, and fine-grained slates. At the falls were metamorphic slates and other hard crystalline rocks; many of these split into flat slabs, well adapted for building, or even for paving, instead of the stones now imported from Portugal into Pará. In the serras of Montealegre, on the north bank of the Amazon, are a great variety of rocks,—coarse quartz conglomerates, fine crystalline sandstones, soft beds of yellow and red sandstones, and indurated clay rocks. These beds are all nearly horizontal, but are much cleft and shattered vertically; they are alternately hard and soft, and by their unequal decay have formed the hanging stones and curious cave described in my Journal.

The general impression produced by the examination of the country is, that here we see the last stage of a process that has been going on, during the whole period of the elevation of the Andes and the mountains of Brazil and Guiana, from the ocean. At the commencement of this period, the greater portion of the valleys of the Amazon, Orinooko, and La Plata must have formed a part of the ocean, separating the groups of islands (which those elevated lands formed on their first appearance) from each other. The sediment carried down into this sea by the rapid streams, running down the sides of these mountains, would tend to fill up and level the deeper and more irregular depressions, forming those large tracts of alluvial deposits we now find in the midst of the granite districts. At the same time volcanic forces were in operation, as shown by the isolated granite peaks which in many places rise out of the flat forest district, like islands from a sea of verdure, because their lower slopes, and the valleys between them, have been covered and filled up by the sedimentary deposits. This simultaneous action of the aqueous and volcanic forces, of submarine earthquakes and marine currents, shaking up, as it were, and levelling the mass of sedimentary matter brought down from the now increasing surface of dry land, is what has produced that marvellous regularity of surface, that gradual and imperceptible slope, which exists over such an immense area.5

At the point where the mountains of Guiana approach nearest to the chain of the Andes, the volcanic action appears to have been continued in the interval between them, throwing up the serras of Curicuriarí, Tunuhy, and the numerous smaller granite mountains of the Uaupés; and it is here probably that dry land first appeared, connecting Guiana and New Granada, and forming that slightly elevated ridge which is now the watershed between the basins of the Amazon and Orinooko. The same thing occurs in the southern part of the continent, for it is where the mountains of Brazil, and the eastern range of the Bolivian Andes, stretch out to meet each other, that the sedimentary deposits in that part appear to have been first raised above the water, and thus to have determined the limits of the basin of the Amazon on the south. The Amazon valley would then have formed a great inland gulf or sea, about two thousand miles long and seven or eight hundred wide.

The rivers and mountain-torrents pouring into it on every side, would gradually fill up this great basin; and the volcanic action still visible in the scoriæ of the Tocantins and Tapajoz, and the shattered rocks of Montealegre, would all tend to the levelling of the vast area, and to determining the channels of the future rivers. This process, continuing for ages, would at length narrow this inland sea, almost within the limits of what is now gapó, or flooded land. Ridges, gradually elevated a few feet above the waters, would separate the tributary streams; and then the eddies and currents would throw up sandbanks as they do now, and gradually define the limits of the river, as we now see it. And changes are yet going on. New islands are yearly forming in the stream, large tracts of flooded land are being perceptibly raised by the deposits upon them, and the numerous great lakes are becoming choked with aquatic plants, and filled up with sediment.

The large extent of flat land on the banks of the river will still continue to be flooded, till some renewed earthquakes raise it gradually above the waters; during which time the stream will work for itself a wider and deeper bed, capable of containing its accumulated flood. In the course of ages perhaps this might be produced by the action of the river itself, for at every annual inundation a deposit of sediment is formed, and these lands must therefore be rising, and would in time become permanently elevated above the highest rise of the river. This, however, would take a very long time, for as the banks rose, the river, unable to spread its waters over the adjoining country, would swell higher, and flow more rapidly than before, and so overflow a country elevated above the level of its former inundations.