полная версия

полная версияTravels on the Amazon

The next morning, after breakfasting with the Commandante, we proceeded on our way. Above São Gabriel the rapids are perhaps more numerous than below. We twisted about the river, round islands and from rock to rock, in a most complicated manner. On a point where we stayed for the night I saw the first tree-fern I had yet met with, and looked on it with much pleasure, as an introduction to a new and interesting district: it was a small, thin-stemmed, elegant species, about eight or ten feet high. At night, on the 22nd, we passed the last rapid, and now had smooth water before us for the rest of our journey. We had thus been four days ascending these rapids, which are about thirty miles in length. The next morning we entered the great and unknown river "Uaupés," from which there is another branch into the Rio Negro, forming a delta at its mouth. During our voyage I had heard much of this river from Senhor L., who was an old trader up it, and well acquainted with the numerous tribes of uncivilised Indians which inhabit its banks, and with the countless cataracts and rapids which render its navigation so dangerous and toilsome. Above the Uaupés the Rio Negro was calm and placid, about a mile, or sometimes two to three miles wide, and its waters blacker than ever.

On the 24th of October, early in the morning, we reached the little village of Nossa Senhora da Guía, where Senhor L. resided, and where he invited me to remain with him as long as I felt disposed.

The village is situated on high ground sloping down suddenly to the river. It consists of a row of thatched mud-huts, some of them whitewashed, others the colour of the native earth. Immediately behind are some patches of low sandy ground, covered with a shrubby vegetation, and beyond is the virgin forest. Senhor L.'s house had wooden doors, and shutters to the windows, as had also one or two others. In fact, Guía was once a very populous and decent village, though now as poor and miserable as all the others of the Rio Negro. Going up to the house I was introduced to Senhor L.'s family, which consisted of two grown-up daughters, two young ones, and a little boy of eight years old. A good-looking "mamelúca," or half-breed woman, of about thirty, was introduced as the "mother of his younger children." Senhor L. had informed me during the voyage that he did not patronise marriage, and thought everybody a great fool who did. He had illustrated the advantages of keeping oneself free of such ties by informing me that the mother of his two elder daughters having grown old, and being unable to bring them up properly or teach them Portuguese, he had turned her out of doors, and got a younger and more civilised person in her place. The poor woman had since died of jealousy, or "passion," as he termed it. When young, she had nursed him during an eighteen months' illness and saved his life; but he seemed to think he had performed a duty in turning her away,—for, said he, "She was an Indian, and could only speak her own language, and, so long as she was with them, my children would never learn Portuguese."

The whole family welcomed him in a very cold and timid manner, coming up and asking his blessing as if they had parted from him the evening before, instead of three months since. We then had some coffee and breakfast; after which the canoe was unloaded, and a little house just opposite his, which happened to be unoccupied, was swept out for me. My boxes were placed in it, my hammock hung up, and I soon made myself comfortable in my new quarters, and then walked out to look about me.

In the village were about a dozen houses belonging to Indians, all of whom had their sitios, or country-houses, at from a few hours' to some days' distance up or down the river, or on some of the small tributary streams. They only inhabit the village at times of festas, or on the arrival of a merchant like Senhor L., when they bring any produce they may have to dispose of or, if they have none, get what goods they can on credit, with the promise of payment at some future time.

There were now several families in the village to welcome their sons and husbands, who had formed our crew; and for some days there was a general drinking and dancing from morning to night. During this time, I took my gun into the woods, in order to kill a few birds. Immediately behind the house were some fruit-trees, to which many chatterers and other pretty birds resorted, and I managed to shoot some every day. Insects were very scarce in the forest; but on the river-side there were often to be found rare butterflies, though not in sufficient abundance to give me much occupation. In a few days, Senhor L. got a couple of Indians to come and hunt for me, and I hoped then to have plenty of birds. They used the gravatána, or blow-pipe, a tube ten to fifteen feet in length, through which they blow small arrows with such force and precision, that they will kill birds or other game as far off, and with as much certainty, as with a gun. The arrows are all poisoned, so that a very small wound is sufficient to bring down a large bird. I soon found that my Indians had come at Senhor L.'s bidding, but did not much like their task; and they frequently returned without any birds, telling me they could not find any, when I had very good reason to believe they had spent the day at some neighbouring sitio. At other times, after a day in the forest, they would bring a little worthless bird, which can be found around every cottage. As they had to go a great distance in search of good birds, I had no hold upon them, and was obliged to take what they brought me, and be contented. It was a great annoyance here, that there were no good paths in the forest, so that I could not go far myself, and in the immediate vicinity of the village there is little to be obtained.

I found it more easy to procure fishes, and was much pleased by being frequently able to add to my collection of drawings. The smaller species I also preserved in spirits. The electrical eel is common in all the streams here; it is caught with a hook, or in weirs, and is eaten, though not much esteemed. When the water gets low, and leaves pools among the rocks, many fish are caught by poisoning the waters with a root called "timbo." The mouths of the small streams are also staked across, and large quantities of all kinds are obtained. The fish thus caught are very good when fresh, but putrefy sooner than those caught in weirs or hooked.

Not being able to do much here, I determined to take a trip up a small stream to a place where, on a lonely granite mountain, the "Cocks of the Rock" are found. An Indian, who could speak a little Portuguese, having come from a village near it, I agreed to return with him. Senhor L. lent me a small canoe; and my two hunters, one of whom lived there, accompanied me. I took with me plenty of ammunition, a great box for my birds, some salt, hooks, mirrors, knives, etc., for the Indians, and left Guía early one morning. Just below the village we turned into the river Isanna, a fine stream, about half a mile wide, and in the afternoon reached the mouth of the small river Cobati (fish), on the south side, which we entered. We had hitherto seen the banks clothed with thick virgin forest, and here and there were some low hills covered entirely with lofty trees. Now the country became very bushy and scrubby; in parts sandy and almost open; perfectly flat, and apparently inundated at the high floods. The water was of a more inky blackness; and the little stream, not more than fifty yards wide, flowed with a rapid current, and turned and doubled in a manner that made our progress both difficult and tedious. At night we stopped at a little piece of open sandy ground, where we drove stakes in the earth to hang our hammocks. The next morning at daybreak we continued our journey. The whole day long we wound about, the stream keeping up exactly the same bleak character as before;—not a tree of any size visible, and the vegetation of a most monotonous and dreary character. At night we stayed near a lake, where the Indians caught some fine fish, and we made a good supper. The next day we wound about more than ever; often, after an hour's hard rowing, returning to within fifty yards of a point we had started from. At length, however, early in the afternoon, the aspect of the country suddenly changed; lofty trees sprang up on the banks, the characteristic creepers hung in festoons over them; moss-covered rocks appeared; and from the river gradually rose up a slope of luxuriant virgin forest, whose varied shades of green and glistening foliage were most grateful to the eye and the imagination, after the dull, monotonous vegetation of the previous days.

In half an hour more we were at the village, which consisted of five or six miserable little huts imbedded in the forest. Here I was introduced to my conductor's house. It contained two rooms, with a floor of earth, and smoky thatch overhead. There were three doors, but no windows. Near one of these I placed my bird-box, to serve as a table, and on the other side swung my hammock. We then took a little walk to look about us. Paths led to the different cottages, in which were large families of naked children, and their almost naked parents. Most of the houses had no walls, but were mere thatched sheds supported on posts, and with sometimes a small room enclosed with a palm-leaf fence, to make a sleeping apartment. There were several young boys here of from ten to fifteen years of age, who were my constant attendants when I went into the forest. None of them could speak a single word of Portuguese, so I had to make use of my slender stock of Lingoa Geral. But Indian boys are not great talkers, and a few monosyllables would generally suffice for our communications. One or two of them had blow-pipes, and shot numbers of small birds for me, while others would creep along by my side and silently point out birds, or small animals, before I could catch sight of them. When I fired, and, as was often the case, the bird flew away wounded, and then fell far off in the forest, they would bound away after it, and seldom search in vain. Even a little humming-bird, falling in a dense thicket of creepers and dead leaves, which I should have given up looking for in despair, was always found by them.

One day I accompanied the Indian with whom I lived into the forest, to get stems for a blow-pipe. We went, about a mile off, to a place where numerous small palms were growing: they were the Iriartea setigera of Martius, from ten to fifteen feet high, and varying from the thickness of one's finger to two inches in diameter. They appear jointed outside, from the scars of the fallen leaves, but within have a soft pith, which, when cleared out, leaves a smooth, polished bore. My companion selected several of the straightest he could find, both of the smallest and largest diameter. These stems were carefully dried in the house, the pith cleared out with a long rod made of the wood of another palm, and the bore rubbed clean and polished with a little bunch of roots of a tree-fern, pulled backwards and forwards through it. Two stems are selected of such a size, that the smaller can be pushed inside the larger; this is done, so that any curve in the one may counteract that in the other; a conical wooden mouthpiece is then fitted on to one end, and sometimes the whole is spirally bound with the smooth, black, shining bark of a creeper. Arrows are made of the spinous processes of the Patawá (Œnocarpus Batawa) pointed, and anointed with poison, and with a little conical tuft of tree cotton (the silky covering of the seeds of a Bombax) at the other end, to fill up exactly, but not tightly, the bore of the tube: these arrows are carried in a wicker quiver, well covered with pitch at the lower part, so that it can be inverted in wet weather to keep the arrows dry. The blow-pipe, or gravatána, is the principal weapon here. Every Indian has one, and seldom goes into the forest, or on the rivers, without it.

I soon found that the Cocks of the Rock, to obtain which was my chief object in coming here, were not to be found near the village. Their principal resort was the Serra de Cobáti, or mountain before mentioned, situated some ten or twelve miles off in the forest, where I was informed they were very abundant. I accordingly made arrangements for a trip to the Serra, with the intention of staying there a week. By the promise of good payment for every "Gallo" they killed for me, I persuaded almost the whole male population of the village to accompany me. As our path was through a dense forest for ten miles, we could not load ourselves with much baggage: every man had to carry his gravatána, bow and arrows, rédé, and some farinha; which, with salt, was all the provisions we took, trusting to the forest for our meat; and I even gave up my daily and only luxury of coffee.

We started off, thirteen in number, along a tolerable path. In about an hour we came to a mandiocca-field and a house, the last on the road to the Serra. Here we waited a short time, took some "mingau," or gruel, made of green plantains, and got a volunteer to join our company. I was much struck with an old woman whose whole body was one mass of close deep wrinkles, and whose hair was white, a sure sign of very great age in an Indian; from information I obtained, I believe she was more than a hundred years old. There was also a young "mamelúca," very fair and handsome, and of a particularly intelligent expression of countenance, very rarely seen in that mixed race. The moment I saw her I had little doubt of her being a person of whom I had heard Senhor L. speak as the daughter of the celebrated German naturalist, Dr. Natterer, by an Indian woman. I afterwards saw her at Guía, and ascertained that my supposition was correct. She was about seventeen years of age, was married to an Indian, and had several children. She was a fine specimen of the noble race produced by the mixture of the Saxon and Indian blood.

Proceeding onwards, we came to another recently-cleared mandiocca-field. Here the path was quite obliterated, and we had to cross over it as we could. Imagine the trees of a virgin forest cut down so as to fall across each other in every conceivable direction. After lying a few months they are burnt; the fire, however, only consumes the leaves and fine twigs and branches; all the rest remains entire, but blackened and charred. The mandiocca is then planted without any further preparation; and it was across such a field that we, all heavily laden, had to find our way. Now climbing on the top of some huge trunk, now walking over a shaking branch or creeping among a confused thicket of charcoal, few journeys require more equanimity of temper than one across an Amazonian clearing.

Passing this, we got into the forest. At first the path was tolerable; soon, however, it was a mere track a few inches wide, winding among thorny creepers, and over deep beds of decaying leaves. Gigantic buttress trees, tall fluted stems, strange palms, and elegant tree-ferns were abundant on every side, and many persons may suppose that our walk must necessarily have been a delightful one; but there were many disagreeables. Hard roots rose up in ridges along our path, swamp and mud alternated with quartz pebbles and rotten leaves; and as I floundered along in the barefooted enjoyment of these, some overhanging bough would knock the cap from my head or the gun from my hand; or the hooked spines of the climbing palms would catch in my shirt-sleeves, and oblige me either to halt and deliberately unhook myself, or leave a portion of my unlucky garment behind. The Indians were all naked, or, if they had a shirt or trousers, carried them in a bundle on their heads, and I have no doubt looked upon me as a good illustration of the uselessness and bad consequences of wearing clothes upon a forest journey.

After four or five hours' hard walking, at a pace which would not have been bad upon clear level ground, we came to a small stream of clear water, which had its source in the Serra to which we were going. Here we waited a few moments to rest and drink, while doing which we heard a strange rush and distant grunt in the forest. The Indians started up, all excitement and animation: "Tyeassú!" (wild hogs) they cried, seizing their bows and arrows, tightening the strings, and grasping their long knives. I cocked my gun, dropped in a bullet, and hoped to get a shot at a "porco;" but being afraid, if I went with them, of losing myself in the forest, I waited with the boys in hopes the game would pass near me. After a little time we heard a rushing and fearful gnashing of teeth, which made me stand anxiously expecting the animals to appear; but the sound went further off, and died away at length in the distance.

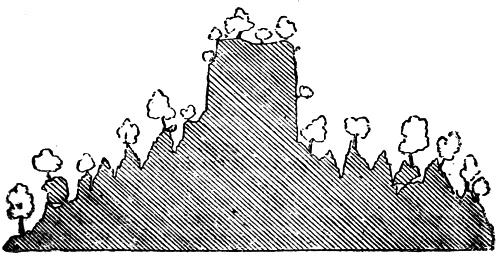

The party now appeared, and said that there was a large herd of fine pigs, but that they had got away. They, however, directed the boys to go on with me to the Serra, and they would go again after the herd. We went on accordingly over very rough, uneven ground, now climbing up steep ascents over rotting trunks of fallen trees, now descending into gullies, till at length we reached a curious rock—a huge table twenty or thirty feet in diameter, supported on two points only, and forming an excellent cave; round the outer edge we could stand upright under it, but towards the centre the roof was so low that one could only lie down. The top of this singular rock was nearly flat, and completely covered with forest-trees, and it at first seemed as if their weight must overbalance it from its two small supports; but the roots of the trees, not finding nourishment enough from the little earth on the top of the rock, ran along it to the edge, and there dropped down vertically and penetrated among the broken fragments below, thus forming a series of columns of various sizes supporting the table all round its outer edge. Here, the boys said, was to be our abode during our stay, though I did not perceive any water near it. Through the trees we could see the mountain a quarter or half a mile from us,—a bare, perpendicular mass of granite, rising abruptly from the forest to a height of several hundred feet.

We had hung up our rédés and waited about half an hour, when three Indians of our party made their appearance, staggering under the weight of a fine hog they had killed, and had slung on a strong pole. I then found the boys had mistaken our station, which was some distance further on, at the very foot of the Serra, and close to a running stream of water, where was a large roomy cave formed by an immense overhanging rock. Over our heads was growing a forest, and the roots again hung down over the edge, forming a sort of screen to our cave, and the stronger ones serving for posts to hang our rédés. Our luggage was soon unpacked, our rédés hung, a fire lighted, and the pig taken down to the brook, which ran at the lower end of the cave, to be skinned and prepared for cooking.

The animal was very like a domestic pig, but with a higher back, coarser and longer bristles, and a most penetrating odour. This I found proceeded from a gland situated on the back, about six inches above the root of the tail: it was a swelling, with a large pore in the centre, from which exuded an oily matter, producing a most intense and unbearable pigsty smell, of which the domestic animal can convey but a faint idea. The first operation of the Indians was to cut out this part completely, and the skin and flesh for some inches all round it, and throw the piece away. If this were not done, they say, the "pitiú" (catinga, Port.), or bad smell, would render all the meat uneatable. The animal was then skinned, cut up into pieces, some of which were put into an earthen pot to stew, while the legs and shoulders were kept to smoke over the fire till they were thoroughly dry, as they can thus be preserved several weeks without salt.

The greater number of the party had not yet arrived, so we ate our suppers, expecting to see them soon after sunset. However, as they did not appear, we made up our fires, put the meat on the "moqueen," or smoking stage, and turned comfortably into our rédés. The next morning, while we were preparing breakfast, they all arrived, with the produce of their hunting expedition. They had killed three hogs, but as it was late and they were a long way off, they encamped for the night, cut up the animals, and partially smoked all the prime pieces, which they now brought with them carefully packed up in palm-leaves. The party had no bows and arrows, but had killed the game with their blow-pipes, and little poisoned arrows about ten inches long.

After breakfast was over we prepared for an attack upon the "Gallos." We divided into three parties, going in different directions. The party which I accompanied went to ascend the Serra itself as far as practicable. We started out at the back of our cave, which was, as I have stated, formed by the base of the mountain itself. We immediately commenced the ascent up rocky gorges, over huge fragments, and through gloomy caverns, all mixed together in the most extraordinary confusion. Sometimes we had to climb up precipices by roots and creepers, then to crawl over a surface formed by angular rocks, varying from the size of a wheelbarrow to that of a house. I could not have imagined that what at a distance appeared so insignificant, could have presented such a gigantic and rugged scene. All the time we kept a sharp look-out, but saw no birds. At length, however, an old Indian caught hold of my arm, and whispering gently, "Gallo!" pointed into a dense thicket. After looking intently a little while, I caught a glimpse of the magnificent bird sitting amidst the gloom, shining out like a mass of brilliant flame. I took a step to get a clear view of it, and raised my gun, when it took alarm and flew off before I had time to fire. We followed, and soon it was again pointed out to me. This time I had better luck, fired with a steady aim, and brought it down. The Indians rushed forward, but it had fallen into a deep gully between steep rocks, and a considerable circuit had to be made to get it. In a few minutes, however, it was brought to me, and I was lost in admiration of the dazzling brilliancy of its soft downy feathers. Not a spot of blood was visible, not a feather was ruffled, and the soft, warm, flexible body set off the fresh swelling plumage in a manner which no stuffed specimen can approach. After some time, not finding any more gallos, most of the party set off on an excursion up a more impracticable portion of the rock, leaving two boys with me till they returned. We soon got tired of waiting, and as the boys made me understand that they knew the path back to our cave, I determined to return. We descended deep chasms in the rocks, climbed up steep precipices, descended again and again, and passed through caverns with huge masses of rocks piled above our heads. Still we seemed not to get out of the mountain, but fresh ridges rose before us, and more fearful fissures were to be passed. We toiled on, now climbing by roots and creepers up perpendicular walls, now creeping along a narrow ledge, with a yawning chasm on each side of us. I could not have imagined such serrated rocks to exist. It appeared as if a steep mountain-side had been cut and hacked by some gigantic force into fissures and ravines, from fifty to a hundred feet deep. My gun was a most inconvenient load when climbing up these steep and slippery places, and I did it much damage by striking its muzzle against the hard granite rock. At length we appeared to have got into the very heart of the mountain: no outlet was visible, and through the dense forest and matted underwood, with which every part of these rocks were covered, we could only see an interminable succession of ridges, and chasms, and gigantic blocks of stone, with no visible termination. As it was evident the boys had lost their way, I resolved to turn back. It was a weary task. I was already fatigued enough, and the prospect of another climb over these fearful ridges, and hazardous descent into those gloomy chasms, was by no means agreeable. However, we persevered, one boy taking my gun; and after about an hour's hard work we got back to the place whence we had started, and found the rest of the party expecting us. We then went down by the proper path, which they told me was the only known way of ascending and descending the mountain, and by which we soon arrived at our cave.

The accompanying sketch gives a section of this mountain, as near as I can make it out. The extraordinary jaggedness of the rocks is not at all exaggerated, and is the more surprising when you get into it, because from a distance it appears one smooth forest-covered hill, of very inconsiderable height, and of a gradual slope. Besides the great caverns and ridges shown above, the surfaces of each precipice are serrated in a most extraordinary manner, forming deep sloping gutters, cut out of the smooth face of the rock, or sometimes vertical channels, with angular edges, such as might be supposed to be formed were the granite in a plastic state forced up against hard angular masses.