полная версия

полная версияThe Evolution of Photography

“Mr. Warren De la Rue exhibited to the Astronomical Society, November, 1857, photographs of the moon and Jupiter, taken by the collodion process in five seconds, of which the Astronomer-Royal said, ‘that a step of very great importance had been made, and that, either as regards the self-delineation of clusters of stars, nebulæ, and planets, or the self-registration of observations, it is impossible at present to estimate the value.’ When admiring the magnificent photographic prints which are now to be seen in almost every part of the civilized world, an involuntary sense of gratitude towards the discoverer of the collodion process must be experienced, and it cannot but be felt how much the world is indebted to Mr. Archer for having placed at its command the means by which such beautiful objects are presented. How many thousands amongst those who owe their means of subsistence to this process must have experienced such a feeling of gratitude? It is upon such considerations that the public have been, and still are, invited to assist in securing for the orphan children of the late Mr. Archer some fitting appreciation of the service which he rendered to science, art, his country—nay, to the whole world.

“M. Digby Wyatt, Chairman,“Jabez Hogg, Secretary to Committee.“Society of Arts, July, 1858.”

After reading that report, and especially Mr. Hunt’s remarks, it will appear evident to all that even that act of charity, gratitude, and justice could not be carried through without someone raising objections and questioning the claims of Frederick Scott Archer as the original inventor of the Collodion process. Nearly all the biographers and historians of photography have coupled other names with Archer’s, either as assistants or co-inventors, but I have evidence in my possession that will prove that neither Fry nor Diamond afforded Archer any assistance whatever, and that Archer preceded all the other claimants in his application of collodion. In support of the first part of this statement, I shall give extracts from Mrs. Archer’s letter, now in my possession, which, I think, will set that matter at rest for ever. Mrs. Archer, writing from Bishop Stortford on December 7th, 1857, says, “When Mr. A. prepared pupils for India he always taught the paper process as well as the Collodion, for fear the chemicals should cause disappointment in a hot climate, as I believe that the negative paper he prepared differed from that in general use. I enclosed a specimen made in our glass house.

“In Mr. Hunt’s book, as well as Mr. Horne’s, Mr. Fry’s name is joined with Mr. Archer’s as the originators of the Collodion process.

“Should Mr. Hunt seem to require any corroboration of what I have stated respecting Mr. Fry, I can send you many of Mr. Fry’s notes of invitation, when Mr. A. merely gave him lessons in the application of collodion, and Mr. Brown gave me the correspondence which passed between him and Mr. Fry on the subject at the time Mr. Home’s book was published. I did not send up those papers, for, unless required, it is useless to dwell on old grievances, but I should like such a man as Mr. Hunt to understand how the association of the two names originated.”

As to priority of application, the following letter ought to settle that point:—

“Alma Cottage, Bishop Stortford.“9th December, 1857.“Sir,—My hunting has at length proved successful. In the enclosed book you will find notes respecting the paper pulp, albumen, tanno-gelatine, and collodion. You will therein see Mr. Archer’s notes of iod-collodion in 1849. You may wonder that I could not find this note-book before, but the numbers of papers that there are, and the extreme disorder, defy description. My head was in such a deplorable state before I left that I could arrange nothing. Those around me were most anxious to destroy all the papers, and I had great trouble to keep all with Mr. Archer’s handwriting upon them, however dirty and rubbishing they might appear, so they were huddled together, a complete chaos. I look back with the greatest thankfulness that my brain did not completely lose its balance, for I had not a single relative who entered into Mr. Archer’s pursuits, so that they could not possibly assist me.

“Mr. Archer being of so reserved a character, I had to find out where everything was, and my search has been amongst different things. I need not tell you that I hope this dirty enclosure will be taken care of.

“The paper pulp occupied much time; in fact, notes were only made of articles which had been much tried, which might probably be brought into use.—I am, sir, yours faithfully,

“J. Hogg, Esq.

F. G. Archer.”If the foregoing is not evidence sufficient, I have by me a very good glass positive of Hever Castle, Kent, which was taken in the spring of 1849, and two collodion negatives made by Mr. Archer in the autumn of 1848; and these dates are all vouched for by Mr. Jabez Hogg, who was Mr. Archer’s medical attendant and friend, and knew him long before he began his experiments with collodion—whereas I cannot find a trace even of the suggestion of the application of collodion in the practice of photography either by Gustave Le Gray or J. R. Bingham prior to 1849; while Mr. Archer’s note-book proves that he was not only iodizing collodion at that date, but making experiments with paper pulp and gelatine; so that Mr. Archer was not only the inventor of the collodion process, but was on the track of its destroyer even at that early date. He also published his method of bleaching positives and intensifying negatives with bichloride of mercury.

Frederick Scott Archer was born at Bishop Stortford in 1813, but there is little known of his early life, and what little there is I will allow Mrs. Archer to tell in her own way.

“Dear Sir,—I do not know whether the enclosed is what you require; if not, be kind enough to let me know, and I must try to supply you with something better. I thought you merely required particulars relating to photography. Otherwise Mr. Archer’s career was a singular one: Losing his parents in childhood, he lived in a world of his own; I think you know he was apprenticed to a bullion dealer in the city, where the most beautiful antique gems and coins of all nations being constantly before him, gave him the desire to model the figures, and led him to the study of numismatics. He worked so hard at nights at these pursuits that his master gave up the last two years of his time to save his life. He only requested him to be on the premises, on account of his extreme confidence in him.

“Many other peculiarities I could mention, but I dare say you know them already.

“I will send a small case to you, containing some early specimens and gutta-percha negatives, with a copy of Mr. A.’s portrait, which I found on leaving Great Russell Street, and have had several printed from it. It is not a good photograph, but I think you will consider it a likeness. I am, yours faithfully,

“J. Hogg, Esq.

F. G. Archer.”Frederick Scott Archer pursued the double occupation of sculptor and photographer at 105, Great Russell Street. It was there he so persistently persevered in his photographic experiments, and there he died in May, 1857, and was interred in Kensal Green Cemetery. A reference to the report of the Committee will show what was done for his bereaved family—a widow and three children. Mrs. Archer followed her husband in March, 1858, and two of the children died early; but one, Alice (unmarried), is still alive and in receipt of the Crown pension of fifty pounds per annum.

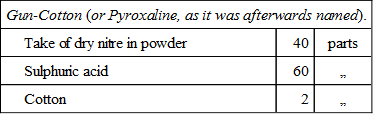

While the collodion episode in the history of photography is before my readers, and especially as the process is rapidly becoming extinct, I think this will be a suitable place to insert Archer’s instructions for making a soluble gun-cotton, iodizing collodion, developing, and fixing the photographic image.

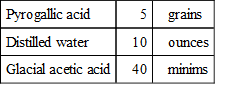

The sulphuric acid and the nitre were mixed together, and immediately the latter was all dissolved, the gun-cotton was added and well stirred with a glass rod for about two minutes; then the cotton was plunged into a large bowl of water and well washed with repeated changes of water until the acid and nitre were washed away. The cotton was then pressed and dried, and converted into collodion by dissolving 30 grains of gun-cotton in 18 fluid ounces of ether and 2 ounces of alcohol—putting the cotton into the ether first, and then adding the alcohol; the collodion allowed to settle and decanted prior to iodizing. The latter operation was performed by adding a sufficient quantity of iodide of silver to each ounce of the plain collodion. Mr. Archer tells how to make the iodide of silver, but the quantity is regulated by the quantity of alcohol in the collodion. When the iodized collodion was ready for use, a glass plate was cleaned and coated with it, and then sensitised by immersion in a bath of nitrate of silver solution—30 grains of nitrate of silver to each ounce of distilled water. From three to five minutes’ immersion in the silver bath was generally sufficient to sensitise the plate. This, of course, had to be done in what is commonly called a dark room. After exposure in the camera, the picture was developed by pouring over the surface of the plate a solution of pyrogallic acid of the following proportions:—

After the development of the picture it was washed and fixed in a solution of hyposulphite of soda, 4 ounces to 1 pint of water. The plate was then washed and dried. This is an epitome of the whole of Archer’s process for making either negatives or positives on glass, the difference being effected by varying the time of exposure and development. Of course the process was somewhat modified and simplified by experience and commercial enterprise. Later on bromides were added to the collodion, an iron developer employed, and cyanide of potassium as a fixing agent; but the principle remained the same from first to last.

When pyrogallic acid was first employed in photography, it was quoted at 21s. per oz., and, if I remember rightly, I paid 3s. for the first drachm that I purchased. On referring to an old price list I find Daguerreotype plates, 21⁄2 by 2 inches, quoted at 12s. per dozen; nitrate of silver, 5s. 6d. per oz.; chloride of gold, 5s. 6d. for 15 grains; hyposulphite of soda at 5s. per lb.; and a half-plate rapid portrait lens by Voightlander, of Vienna, at £60. Those were the days when photography might well be considered expensive, and none but the wealthy could indulge in its pleasures and fascinations.

While I lived in Glasgow, competition was tolerably keen, even then, and amongst the best “glass positive men” were Messrs. Bibo, Bowman, J. Urie, and Young and Sun, as the latter styled himself; and in photographic portraiture, plain and coloured, by the collodion process, were Messrs. Macnab and J. Stuart. From the time that I relinquished the Daguerreotype process, in 1857, I devoted my attention to the production of high-class collodion negatives. I never took kindly to glass positives, though I had done some as early as 1852. They were never equal in beauty and delicacy to a good Daguerreotype, and their low tone was to me very objectionable. I considered the Ferrotype the best form of collodion positive, and did several of them, but my chief work was plain and coloured prints from collodion negatives, also small portraits on visiting cards.

Early in January, 1860, my home and business were destroyed by fire, and I lost all my old and new specimens of Daguerreotypes and photographs, all my Daguerreotype and other apparatus, and nearly everything I possessed. As I was only partially insured, I suffered considerable loss. After settling my affairs I decided on going to America again and trying my luck in New York. Family ties influenced this decision considerably, or I should not have left Glasgow, where I was both prosperous and respected. To obtain an idea of the latest and best aspects of photography, I visited London and Paris.

The carte-de-visite form of photography had not exhibited much vitality at that period in London, but in Paris it was beginning to be popular. While in London I accompanied Mr. Jabez Hughes to the meeting of the Photographic Society, Feb. 7th, 1860, the Right Honorable the Lord Chief Baron Pollock in the chair, when the report of the Collodion Committee was delivered. The committee, consisting of F. Bedford, P. Delamotte, Dr. Diamond, Roger Fenton, Jabez Hughes, T. A. Malone, J. H. Morgan, H. P. Robinson, Alfred Rosling, W. Russell Sedgefield, J. Spencer, and T. R. Williams, strongly recommended Mr. Hardwich’s formula. That was my first visit to the Society, and I certainly did not think then that I should ever see it again, or become and be a member for twenty-two years.

I sailed from Liverpool in the ss. City of Baltimore in March, and reached New York safely in April, 1860. I took time to look about me, and visited all the “galleries” on Broadway, and other places, before deciding where I should locate myself. Many changes had taken place during the six years I had been absent. Nearly all the old Daguerreotypists were still in existence, but all of them, with the exception of Mr. Brady, had abandoned the Daguerreotype process, and Mr. Brady only retained it for small work. Most of the chief galleries had been moved higher up Broadway, and a mania of magnificence had taken possession of most of the photographers. Mr. Anson was the first to make a move in that direction by opening a “superb gallery” on the ground floor in Broadway right opposite the Metropolitan Hotel, filling his windows with life-sized photographs coloured in oil at the back, which he called Diaphanotypes. He did a large business in that class of work, especially among visitors from the Southern States; but that was soon to end, for already there were rumours of war, but few then gave it any serious consideration.

Messrs. Gurney and Sons’ gallery was also a very fine one, but not on the ground floor. Their “saloon” was upstairs, This house was one of the oldest in New York in connection with photography. In the very early days, Mr. Gurney, senr., was one of the most eminent “professors” of the Daguerreotype process, and was one of the committee appointed to wait upon the Rev. Wm. Hill, a preacher in the Catskills, to negotiate with the reverend gentlemen (?) for his vaunted secret of photography in natural colours. As the art progressed, or the necessity for change arose, Mr. Gurney was ready to introduce every novelty, and, in later years, in conjunction with Mr. Fredericks, then in partnership with Mr. Gurney, he introduced the “Hallotype,” not Hillotype, and the “Ivorytype.” Both these processes had their day. The former was photography spoiled by the application of Canada balsam and very little art; the latter was the application of a great deal of art to spoil a photograph. The largest of all the large galleries on Broadway was that of Messrs. Fredericks and Co. The whole of the ground and first floor were thrown into one “crystal front,” and made a very attractive appearance. The windows were filled with life-sized portraits painted in oil, crayons, and other styles, and the walls of the interior were covered with life-sized portraits of eminent men and beautiful women. The floor was richly carpeted, and the furnishing superb. A gallery ran round the walls to enable the visitors to view the upper pictures, and obtain a general view of the “saloon,” the tout ensemble of which was magnificent. From the ground floor an elegant staircase led to the galleries, toilet and waiting rooms, and thence to the operating rooms or studios. Some of the Parisian galleries were fine, but nothing to be compared with Fredericks’, and the finest establishment in London did not bear the slightest comparison.

Mr. Brady was another of the early workers of the Daguerreotype process, and probably the last of his confrères to abandon it. He commenced business in the early forties in Fulton Street, a long way down Broadway, but as the sea of commerce pressed on and rolled over the strand of fashion, he was obliged to move higher and higher up Broadway, until he reached the corner of Tenth Street, nearly opposite Grace Church. Mr. Brady appeared to set the Franklin maxim, “Three removes as bad as a fire,” at defiance, for he had made three or four moves to my knowledge—each one higher and higher to more elegant and expensive premises, each remove entailing the cost of more and more expensive furnishing, until his latest effort in upholstery culminated in a superb suite of black walnut and green silk velvet; in short, Longfellow’s “Excelsior” appeared to be the motto of Mr. Brady.

Messrs. Mead Brothers, Samuel Root, James Cady, and George Adams ought to receive “honourable mention” in connection with the art in New York, for they were excellent operators in the Daguerreotype days, and all were equally good manipulators of the collodion process and silver printing.

After casting and sounding about, like a mariner seeking a haven on a strange coast, I finally decided on buying a half interest in the gallery of Mead Brothers, 805, Broadway; Harry Mead retaining his, or his wife’s share of the business, but leaving me to manage the “uptown” branch. This turned out to be an unfortunate speculation, which involved me in a lawsuit with one of Mead’s creditors, and compelled me to get rid of a very unsatisfactory partner in the best way and at any cost that I could. Mead’s creditor, by some process of law that I could never understand, stripped the gallery of all that belonged to my partner, and even put in a claim for half of the fixtures. Over this I lost my temper, and had to pay, not the piper, but the lawyer. I also found that Mrs. Henry Mead had a bill of sale on her husband’s interest in the business, which I ended by buying her out. Husband and wife are very seldom one in America. Soon after getting the gallery into my own hands, refurnishing and rearranging, the Prince of Wales’s visit to New York was arranged, and as the windows of my gallery commanded a good view of Broadway, I let most of them very advantageously, retaining the use of one only for myself and family. There were so many delays, however, at the City Hall and other places on the day of the procession, that it was almost dark when the Prince reached 805, Broadway, and all my guests were both weary of waiting so long, and disappointed at seeing so little of England’s future King.

When I recommenced business on Broadway on my own account there was only one firm taking cartes-de-visite, and I introduced that form of portrait to my customers, but they did not take very kindly to it, though a house not far from me was doing a very good business in that style at three dollars a dozen, and Messrs. Rockwood and Co. appeared to be monopolising all the carte-de-visite business that was being done in New York; but eventually I got in the thin edge of the wedge by exhibiting four for one dollar. This ruse brought in sitters, and I began to do very well until Abraham Lincoln issued his proclamation calling for one hundred thousand men to stamp out the Southern rebellion. I remember that morning most distinctly. It was a miserably wet morning in April, 1861, and all kinds of business received a shock. People looked bewildered, and thought of nothing but saving their money and reducing their expenses. It had a blighting effect on my business, and I, not knowing, like others, where it might land me, determined to get rid of my responsibilities at any cost, so I sold my business for a great deal less than it was worth, and at a very serious loss. The outbreak of that gigantic civil war and a severe family bereavement combined, induced me to return to England as soon as possible. Before leaving America, in all probability for ever, I went to Washington to bid some friends farewell, and while there I went into Virginia with a friend on Sunday morning, July 21st, and in the afternoon saw the smoke and heard the cannonading of the first battle of Bull Run, and witnessed, next morning, the rout and rush into Washington of the demoralised fragments of the Federal army. I wrote and sent a description of the stampede to a friend in Glasgow, which he handed over to the Glasgow Herald for publication, and I have reason to believe that my description of that memorable rout was the first that was published in Great Britain.

As soon as I could settle my affairs I left New York with my family, and arrived in London on the 15th of September, 1861. It was a beautiful sunny day when I landed, and, after all the trouble and excitement I had so recently seen and experienced, London, despite its business and bustle, appeared like a heaven of peace.

Mr. Jabez Hughes was about the last to wish me “God speed” when I left England, so he was the first I went to see when I returned. I found, to my disappointment, that he was in Paris, but Mrs. Hughes gave me a hearty welcome. After a few days’ sojourn in London I went to Glasgow with the view of recommencing in that city, where I had many friends; but while there, and on the very day that I was about to sign for the lease of a house, Mr. Hughes wrote to offer me the management of his business in Oxford Street. It did not take me long to decide, and by return post that same night I wrote accepting the offer. I concluded all other arrangements as quickly as possible, returned to London, and entered upon my managerial duties on the 1st November, 1861. I had long wished and looked out for an opportunity to settle in London and enlarge my circle of photographic acquaintance and experience, so I put on my new harness with alacrity and pleasure.

Among the earliest of my new acquaintances was George Wharton Simpson, Editor of the Photographic News. He called at Oxford Street one evening while I was the guest of Mr. Hughes, by whom we were introduced, and we spent a long, chatty, and pleasant evening together, talking over my American experience and matters photographic; but, to my surprise, much of our conversation appeared in the next issue of his journal (vide Photographic News, October 11th, 1861, pp. 480-1). But that was a power, I afterwards ascertained, which he possessed to an eminent degree, and which he utilized most successfully at his “Wednesday evenings at home,” when he entertained his photographic friends at Canonbury Road, N. Very delightful and enjoyable those evenings were, and he never failed to cull paragraphs for the Photographic News from the busy brains of his numerous visitors. He was a genial host, and his wife was a charming hostess; and his daughter Eva, now the wife of William Black the novelist, often increased the charm of those evenings by the exhibition of her musical abilities. It is often a wonder to me that other editors of photographic journals don’t pursue a similar plan, for those social re-unions were not only pleasant, but profitable to old friend Simpson. Through Mr. Simpson’s “at homes,” and my connection with Mr. Hughes, I made the acquaintance of nearly all the eminent photographers of the time, amongst whom may be mentioned W. G. Lacy, of Ryde, I.W. The latter was a very sad and brief acquaintanceship, for he died in Mr. Hughes’s sitting-room on the 21st November, 1861, in the presence of G. Wharton Simpson, Jabez Hughes, and myself, and, strangely enough, it was entirely through this death that Mr. Hughes went to Ryde, and became photographer to the Queen. Mr. Lacy made his will in Mr. Hughes’s sitting-room, and Mr. Simpson sole executor, who sold Mr. Lacy’s business in the Arcade, Ryde, I.W., to Mr. Hughes, and in the March following he took possession, leaving me solely in charge of his business in Oxford Street, London.

About this time Mr. Skaife introduced his ingenious pistolgraph, but it was rather in advance of the times, for the dry plates then in the market were not quite quick enough for “snap shots,” though I have seen some fairly good pictures taken with the apparatus.

At this period a fierce controversy was raging about lunar photography, but it was all unnecessary, as the moon had photographed herself under the guidance of Mr. Whipple, of Boston, U.S., as early as 1853, and all that was required to obtain a lunar picture was sufficient exposure.

On December 3rd, 1861, Thomas Ross read a paper and exhibited a panoramic lens and camera at a meeting of the Photographic Society, and on the 15th October, 1889, I saw the same apparatus, in perfect condition, exhibited as a curiosity at the Photographic Society’s Exhibition. No wonder the apparatus was in such good condition, for I should think it had never been used but once. The plates were 10 inches long, and curved like the crescent of a new moon. Cleaning board, dark slide, and printing-frame, were all curved. Fancy the expense and trouble attending the use of such an apparatus; I should think it had few buyers. Certainly I never sold one, and I never met with any person who had bought one.