полная версия

полная версияThe Evolution of Photography

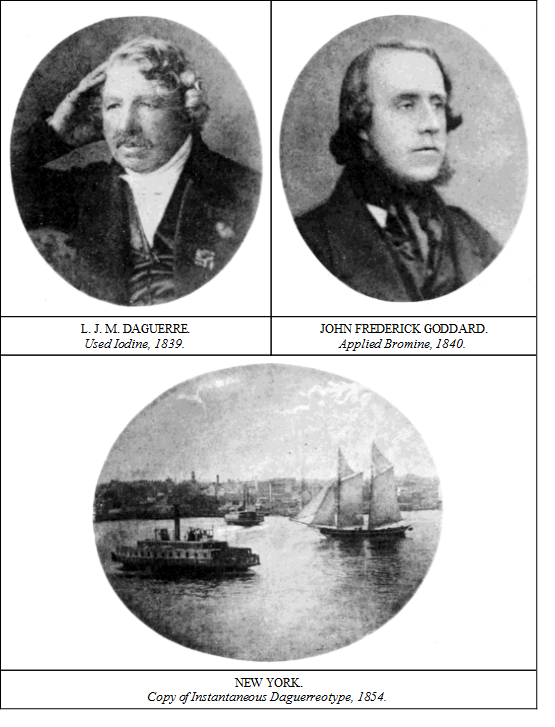

In July, 1839, M. Daguerre divulged his secret at the request and expense of the French Government, and the process which bore his name was found to be totally different, both in manipulation and effect, from any sun-pictures that had been obtained in England. The Daguerreotype was a latent image produced by light on an iodised silver plate, and developed, or made visible, by the fumes of mercury; but the resultant picture was one of the most shimmering and vapoury imaginable, wanting in solidity, colour, and firmness. In fact, photography as introduced by M. Daguerre was in every sense a wonderfully shadowy and all but invisible thing, and not many removes from the dark ages of its creation. The process was extremely delicate and difficult, slow and tedious to manipulate, and too insensitive to be applied to portraiture with any prospect of success, from fifteen to twenty minutes’ exposure in bright sunshine being necessary to obtain a picture. The mode of proceeding was as follows:—A copper plate with a coating of silver was carefully cleaned and polished on the silvered side, that was placed, silver side downwards, over a vessel containing iodine in crystals, until the silvered surface assumed a golden-yellow colour. The plate was then transferred to the camera-obscura, and submitted to the action of light. After the plate had received the requisite amount of exposure, it was placed over a box containing mercury, the fumes of which, on the application of a gentle heat, developed the latent image. The picture was then washed in salt and water, or a solution of hyposulphite of soda, to remove the iodide of silver, washed in clean water afterwards, and dried, and the Daguerreotype was finished according to Daguerre’s first published process.

The development of the latent image by mercury subliming was the most marvellous and unlooked-for part of the process, and it was for that all-important thing that Daguerre was entirely indebted to chance. Having put one of his apparently useless iodized and exposed silver plates into a cupboard containing a pot of mercury, Daguerre was greatly surprised, on visiting the cupboard some time afterwards, to find the blank looking plate converted into a visible picture. Other plates were iodized and exposed and placed in the cupboard, and the same mysterious process of development was repeated, and it was not until this thing and the other thing had been removed and replaced over and over again, that Daguerre became aware that quicksilver, an article that had been used for making mirrors and reflecting images for years, was the developer of the invisible image. It was indeed a most marvellous and unexpected result. Daguerre had devoted years of labour and made numberless experiments to obtain a transcript of nature drawn by her own hand, but all his studied efforts and weary hours of labour had only resulted in repeated failures and disappointments, and it appeared that Nature herself had grown weary of his bungling, and resolved to show him the way.

The realization of his hopes was more accidental than inferential. The compounds with which he worked, neither produced a visible nor a latent image capable of being developed with any of the chemicals with which he was experimenting. At last accident rendered him more service than reasoning, and occult properties produced the effect his mental and inductive faculties failed to accomplish; and here we observe the great difference between the two successful discoverers, Reade and Daguerre. At this stage of the discovery I ignore Talbot’s claim in toto. Reade arrived at his results by reasoning, experiment, observation, and judiciously weakening and controlling the re-agent he commenced his researches with. He had the infinite pleasure and disappointment of seeing his first picture flash into existence, and disappear again almost instantly, but in that instant he saw the cause of his success and failure, and his inductive reasoning reduced his failure to success; whereas Daguerre found his result, was puzzled, and utterly at a loss to account for it, and it was only by a process of blind-man’s bluff in his chemical cupboard that he laid his hands on the precious pot of mercury that produced the visible image.

That was a discovery, it is true; but a bungling one, at best. Daguerre only worked intelligently with one-half of the elements of success; the other was thrust in his way, and the most essential part of his achievement was a triumphant accident. Daguerre did half the work—or, rather, one-third—light did the second part, and chance performed the rest, so that Daguerre’s share of the honour was only one-third. Reade did two-thirds of the process, the first and third, intelligently; therefore to him alone is due the honour of discovering practical photography. His was a successful application of known properties, equal to an invention; Daguerre’s was an accidental result arising from unknown causes and effects, and consequently a discovery of the lowest order. To England, then, and not to France, is the world indebted for the discovery of photography, and in the order of its earliest, greatest, and most successful discoverers and advancers, I place the Rev. J. B. Reade first and highest.

SECOND PERIOD. DAGUERREOTYPE

SECOND PERIOD

PUBLICITY AND PROGRESS

1839 has generally been accepted as the year of the birth of Practical Photography, but that may now be considered an error. It was, however, the Year of Publicity, and the progress that followed with such marvellous rapidity may be freely received as an adversely eloquent comment on the principles of secrecy and restriction, in any art or science, like photography, which requires the varied suggestions of numerous minds and many years of experiment in different directions before it can be brought to a state of workable certainty and artistic and commercial applicability. Had Reade concealed his success and the nature of his accelerator, Talbot might have been bungling on with modifications of the experiments of Wedgwood and Davy to this day; and had Daguerre not sold the secret of his iodine vapour as a sensitiser, and his accidentally discovered property of mercury as a developer, he might never have got beyond the vapoury images he produced. As it was, Daguerre did little or nothing to improve his process and make it yield the extremely vigorous and beautiful results it did in after years. As in Mr. Reade’s case with the Calotype process, Daguerre threw the ball and others caught it. Daguerre’s advertised improvements of his process were lamentable failures and roundabout ways to obtain sensitive amalgams—exceedingly ingenious, but excessively bungling and impractical. To make the plates more sensitive to light, and, as Daguerre said, obtain pictures of objects in motion and animated scenes, he suggested that the silver plate should first be cleaned and polished in the usual way, then to deposit successively layers of mercury, and gold, and platinum. But the process was so tedious, unworkable, and unsatisfactory, no one ever attempted to employ it either commercially or scientifically. In publishing his first process, with its working details, Daguerre appears to have surrendered all that he knew, and to have been incapable of carrying his discovery to a higher degree of advancement. Without Mr. Goddard’s bromine accelerator and M. Fizeau’s chloride of gold fixer and invigorator, the Daguerreotype would never have been either a commercial success or a permanent production.

1840 was almost as important a period in the annals of photography as the year of its enunciation, and to the two valuable improvements and one interesting importation, the Daguerreotype process was indebted for its success all over the world; and photography, even as it is practised now, is probably indebted for its present state of advancement to Mr. John Frederick Goddard, who applied bromine, as an accelerator, to the Daguerreotype process this year. In the early part of the Daguerreotype period it was so insensitive there was very little prospect of being able to take portraits with it through a lens. To meet this difficulty Mr. Wolcott, an American optician, constructed a reflecting camera and brought it to London. It was an ingenious contrivance, but did not fully answer the expectations of the inventor. It certainly did not require such a long exposure with this camera as when the rays from the image or sitter passed through a lens; but, as the sensitised plate was placed between the sitter and the reflector, the picture was necessarily small, and neither very sharp nor satisfactory. This was a mechanical contrivance to shorten the time of exposure, which partially succeeded, but it was chemistry, and not mechanics, that effected the desirable result. Both Mr. Goddard and M. Antoine F. J. Claudet, of London, employed chlorine as a means of increasing the sensitiveness of the iodised silver plate, but it was not sufficiently accelerative to meet the requirements of the Daguerreotype process. Subsequently Mr. Goddard discovered that the vapour of bromine, added to that of iodine, imparted an extraordinary degree of sensitiveness to the prepared plate, and reduced the time of sitting from minutes to seconds. The addition of the fumes of bromine to those of iodine formed a compound of bromo-iodide of silver on the surface of the Daguerreotype plate, and not only increased the sensitiveness, but added to the strength and beauty of the resulting picture, and M. Fizeau’s method of precipitating a film of gold over the whole surface of the plate still further increased the brilliancy of the picture and ensured its permanency. I have many Daguerreotypes in my possession now that were made over forty years ago, and they are as brilliant and perfect as they were on the day they were taken. I fear no one can say the same for any of Fox Talbot’s early prints, or even more recent examples of silver printing.

Another important event of this year was the importation of the first photographic lens, camera, &c., into England. These articles were brought from Paris by Sir Hussey Vivian, present M.P. for Glamorganshire (1889). It was the first lot of such articles that the Custom House officers had seen, and they were at a loss to know how to classify it. Finally they passed it under the general head of Optical Instruments. Sir Hussey told me this, himself, several years before he was made a baronet. What changes fifty years have wrought even in the duties of Custom House officers, for the imports and exports of photographic apparatus and materials must now amount to many thousands per annum!

Having described the conditions and state of progress photography had attained at the time of my first contact with it, I think I may now enter into greater details, and relate my own personal experiences from this period right up to the end of its jubilee celebration.

I was just fourteen years old when photography was made practicable by the publication of the two processes, one by Daguerre, and the other by Fox Talbot, and when I heard or read of the wonderful discovery I was fired with a desire to obtain a sight of these “sun-pictures,” but the fire was kept smouldering for some time before my desire was gratified. Nothing travelled very fast in those days. Railroads had not long been started, and were not very extensively developed. Telegraphy, by electricity, was almost unknown, and I was a fixture, having just been apprenticed to an engraving firm hundreds of miles from London. But at last I caught sight of one of those marvellous drawings made by the sun in the window of the Post Office of my native town. It was a small Daguerreotype which had been sent there along with a notice that a licence to practise the “art” could be obtained of the patentee. I forget now what amount the patentee demanded for a licence, but I know that at the time referred to it was so far beyond my means and hopes that I never entertained the idea of becoming a licencee. I believe some one in the neighbourhood bought a licence, but either could not or did not make use of it commercially.

Some time after that, a Miss Wigley, from London, came to the town to practise Daguerreotyping, but she did not remain long, and could not, I think, have made a profitable visit. If so, it could scarcely be wondered at, for the sun-pictures of that period were such thin, shimmering reflections, and distortions of the human face divine, that very few people were impressed either by the process or the newest wonder of the world. At that early period of photography, the plates were so insensitive, the sittings so long, and the conditions so terrible, it was not easy to induce anyone either to undergo the ordeal of sitting, or to pay the sum of twenty-one shillings for a very small and unsatisfactory portrait. In the infancy of the Daguerreotype process, the sitters were all placed out-of-doors, in direct sunshine, which naturally made them screw up or shut their eyes, and every feature glistened, and was painfully revealed. Many amusing stories have been told about the trials, mishaps, and disappointments attending those long and painful sittings, but the best that ever came to my knowledge was the following. In the earliest of the forties, a young lady went a considerable distance, in Yorkshire, to sit to an itinerant Daguerreotypist for her portrait, and, being limited for time, could only give one sitting. She was placed before the camera, the slide drawn, lens uncapped, and requested to sit there until the Daguerreotypist returned. He went away, probably to put his “mercury box” in order, or to have a smoke, for it was irksome—both to sitter and operator—to sit or stand doing nothing during those necessarily long exposures. When the operator returned, after an absence of fifteen or twenty minutes, the lady was sitting where he left her, and appeared glad to be relieved from her constrained position. She departed, and he proceeded with the development of the picture. The plate was examined from time to time, in the usual way, but there was no appearance of the lady. The ground, the wall, and the chair whereon she sat, were all visible, but the image of the lady was not; and the operator was completely puzzled, if not alarmed. He left the lady sitting, and found her sitting when he returned, so he was quite unable to account for her mysterious non-appearance in the picture. The mystery was, however, explained in a few days, when the lady called for her portrait, for she admitted that she got up and walked about as soon as he left her, and only sat down again when she heard him returning. The necessity of remaining before the camera was not recognised by that sitter. I afterwards reversed that result myself by focussing the chair, drawing the slide, uncapping the lens, sitting down, and rising leisurely to cap the lens again, and obtained a good portrait without showing a ghost of the chair or anything else. The foregoing is evidence of the insensitiveness of the plates at that early period of the practice of photography; but that state of inertion did not continue long, for as soon as the accelerating properties of bromine became generally known, the time of sitting was greatly reduced, and good Daguerreotype views were obtained by simply uncapping the lens as quickly as possible. I have taken excellent views in that manner myself in England, and, when in America, I obtained instantaneous views of Niagara Falls and other places quite as rapidly and as perfect as any instantaneous views made on gelatine dry plates, one of which I have copied and enlarged to 12 by 10 inches, and may possibly reproduce the small copy in these pages.

In 1845 I came into direct contact with photography for the first time. It was in that year that an Irishman named McGhee came into the neighbourhood to practise the Daguerreotype process. He was not a licencee, but no one appeared to interfere with him, nor serve him with an injunction, for he carried on his little portrait business for a considerable time without molestation. The patentee was either very indifferent to his vested interests, or did not consider these intruders worth going to law with, for there were many raids across the borders by camera men in those early days. Several circumstances combined to facilitate the inroads of Scotch operators into the northern counties of England. Firstly, the patent laws of England did not extend to Scotland at that time, so there was a far greater number of Daguerreotypists in Edinburgh and other Scotch towns in the early days of photography than in any part of England, and many of them made frequent incursions into the forbidden land without troubling themselves about obtaining a licence, but somehow they never remained long at a time; they were either afraid of consequences, or did not meet with patronage sufficient to induce them to continue their sojourns beyond a few of the summer weeks. For many years most of the early Daguerreotypists were birds of passage, frequently on the wing. Among the earliest settlers in London, were Mr. Beard (patentee), Mr. Claudet, and Mr. J. E. Mayall—the latter is still alive, 1889—and in Edinburgh, Messrs. Ross and Thompson, Mr. Howie, Mr. Poppawitz, and Mr. Tunny—the latter was a Calotypist—with most of whom it was my good fortune to become personally acquainted in after years.

Secondly, a great deal of ill-feeling and annoyance were caused by the incomprehensible and somewhat underhanded way in which the English patent was obtained, and these feelings induced many to poach on photographic preserves, and even to defy injunctions; and, while lawsuits were pending, it was not uncommon for non-licencees to practise the new art with the impunity and feelings common to smugglers. Mr. Beard, the English patentee, brought many actions at law against infringers of his patent rights, the most memorable of which was that where Mr. Egerton, 1, Temple Street, Whitefriars, the first dealer in photographic materials, and agent for Voightlander’s lenses in London, was the defendant. During that trial it came out in evidence that the patentee had earned as much as forty thousand pounds in one year by taking portraits and fees from licencees. Though the judgment of the Court was adverse to Mr. Egerton, it did not improve the patentee’s moral right to his claim, for the trial only made it all the more public that the French Government had allowed M. Daguerre six thousand francs (£240), and M. Isidore Niépce four thousand francs (£160) per annum, on condition that their discoveries should be published, and made free to all the world. This trial did not in any way improve Mr. Beard’s financial position, for eventually he became a bankrupt, and his establishments in King William Street, London Bridge, and the Polytechnic Institute, in Regent Street, were extinguished. Mr. Beard, who was the first to practise Daguerreotyping commercially in this country, was originally a coal merchant. I think Mr. Claudet practised the process in London without becoming a licencee, either through previous knowledge, or some private arrangement made with Daguerre before the patent was granted to Mr. Beard. It was while photography was clouded with this atmosphere of dissatisfaction and litigation, that I made my first practical acquaintance with it in the following manner:—

Being anxious to obtain possession of one of those marvellous sun-pictures, and hoping to get an idea of the manner in which they were produced, I paid a visit, one sunny morning, to Mr. McGhee, the Daguerreotypist, dressed in my best, with clean shirt, and stiff stand-up collar, as worn in those days. I was a very young man then, and rather particular about the set of my shirt collar, so you may readily judge of my horror when, after making the financial arrangements to the satisfaction of Mr. McGhee, he requested me to put on a blue cotton quasi clean “dickey,” with a limp collar, that had evidently done similar duty many times before. You may be sure I protested, and inquired the reason why I should cover up my white shirt front with such an objectionable article. I was told if I did not put it on my shirt front would be solarized, and come out blue or dirty, whereas if I put on the blue “dickey” my shirt front would appear white and clean. What “solarized” meant, I did not know, nor was it further explained, but, as I very naturally wished to appear with a clean shirt front, I submitted to the indignity, and put on the limp and questionably clean “dickey.” While the Daguerreotypist was engaged with some mysterious manipulations in a cupboard or closet, I brushed my hair, and contemplated my singular appearance in the mirror somewhat ruefully. O, ye sitters and operators of to-day! congratulate yourselves on the changes and advantages that have been wrought in the practice of photography since then. When Mr. McGhee appeared again with something like two wooden books in his hand, he requested me to follow him into the garden; which was only a back yard. At the foot of the garden, and against a brick wall with a piece of grey cloth nailed over it, I was requested to sit down on an old chair; then he placed before me an instrument which looked like a very ugly theodolite on a tripod stand—that was my first sight of a camera—and, after putting his head under a black cloth, told me to look at a mark on the other side of the garden, without winking or moving till he said “done.” How long I sat I don’t know, but it seemed an awfully long time, and I have no doubt it was, for I know that I used to ask people to sit five and ten minutes, afterwards. The sittings over, I was requested to re-enter the house, and then I thought I would see something of the process; but no. Again Mr. McGhee went into the mysterious chamber, and shut the door quickly. In a little time he returned and told me that the sittings were satisfactory—he had taken two—and that he would finish and deliver them next day. Then I left without obtaining the ghost of an idea of the modus operandi of producing portraits by the sun, beyond the fact that a camera had been placed before me. Next day the portraits were delivered according to promise, but I confess I was somewhat disappointed at getting so little for my money. It was a very small picture that could not be seen in every light, and not particularly like myself, but a scowling-looking individual, with a limp collar, and rather dirty-looking face. Whatever would mashers have said or done, if they had gone to be photographed in those days of photographic darkness? I was, however, somewhat consoled by the thought that I, at last, possessed one of those wonderful sun-pictures, though I was ignorant of the means of production.

Soon after having my portrait taken, Mr. McGhee disappeared, and there was no one left in the neighbourhood who knew anything of the mysterious manipulations of Daguerreotyping. I had, nevertheless, resolved to possess an apparatus and obtain the necessary information, but there was no one to tell me what to buy, where to buy it, nor what to do with it. At last an old friend of mine who had been on a visit to Edinburgh, had purchased an apparatus and some materials with the view of taking Daguerreotypes himself, but finding that he could not, was willing to sell it to me, though he could not tell me how to use it, beyond showing me an image of the house opposite upon the ground glass of the camera. I believe my friend let me have the apparatus for what it cost him, which was about £15, and it consisted of a quarter-plate portrait lens by Slater, mahogany camera, tripod stand, buff sticks, coating and mercury boxes of the roughest description, a few chemicals and silvered plates, and a rather singular but portable dark room. Of the uses of the chemicals I knew very little, and of their nature nothing which led to very serious consequences, which I shall relate in the proper place. Having obtained possession of this marvellous apparatus, my next ardent aspiration was to make a successful use of it. I distinctly remember, even at this distant date, with what nervous curiosity I examined all the articles when I unpacked them in my father’s house, and with what wonder, not unmixed with apprehension, my father looked upon that display of unknown, and to him apparently nameless and useless toys. “More like a lot of conjuror’s traps than anything else,” he exclaimed, after I had set them all out. And a few days after he told one of my young friends that he thought I had gone out of my mind to take up with that “Daggertype” business; the name itself was a stumbling block in those days, for people called the process “dagtype, docktype, and daggertype” more frequently than by its proper name, Daguerreotype. What a contrast now-a-days, when almost every father is an amateur photographer, and encourages both his sons and daughters to become the same. My father was a very good parent, in his way, and encouraged me, to the fullest extent of his means, in the study of music and painting, and even sent me to the Government School of Design, where I studied drawing under W. B. Scott; but the new-fangled method of taking portraits did not harmonise with his conservative and practical notions. One cause of his disapprobation and dissatisfaction was, doubtless, my many failures; in fact, I may say, inability to show him any result. I had acquired an apparatus of the roughest and most primitive construction, but no knowledge of its use or the behaviour of the chemicals employed, beyond the bare numerical order in which they were to be used, and there was no one within a hundred miles of where I lived, that I knew of, who could give me lessons or the slightest hint respecting the process. I had worn out the patience of all my relations and friends in fruitless sittings. I had set fire to my singular dark room, and nearly set fire to the house, by attempting to refill the spirit lamp while alight, and I was ill and suffering from salivation through inhaling the fumes of mercury in my blind, anxious, and enthusiastic endeavours to obtain a sun-picture. It is not long since an eminent photographer told me that I was an enthusiast, but if he had seen me in those days he would, in all probability, have told me that I was mad. Though ill, I was not mad; I was only determined not to be beaten. I was resolved to keep pegging away until I obtained a satisfactory result. My friends laughed at me when I asked them to sit for a trial, and they either refused, or sat with a very bad grace, as if it really were a trial to them; but fancy, fair and kindly readers, what it must have been to me! Finding that my living models fought shy of me and my trials, I then thought of getting a lay figure, and borrowed a large doll—quite as big as a baby—of one of my lady friends. I stuck it up in a garden and pegged away at it for nearly six months. At the end of that time I was able to produce a portrait of the doll with tolerable certainty and success. Then I ventured to ask my friends to sit again, but my process was too slow for life studies, and my live sitters generally moved so much, their portraits were not recognisable. There were no head-rests in those days, at least I did not possess one, or it might have been pleasanter for my sitters and easier for myself. What surprised me very much—and I thought it a singular thing at the time—was my success in copying an engraving of Thorburn’s Miniature of the Queen. I made several good and beautiful copies of that engraving, and sent one to an artist-friend, then in Devonshire, who wrote to say that it was beautiful, and that if he could get a Daguerreotype portrait with the eyes as clear as that, he would sit at once; but all the “Dagtypes” he had hitherto seen had only black holes where the eyes should be. Unfortunately, that was my own experience. I could copy from the flat well enough, but when I went to the round I went wrong. Ultimately I discovered the cause of all that, and found a remedy, but oh! the weary labour and mental worry I underwent before I mastered the difficulties of the most troublesome and uncertain, yet most beautiful and permanent of all the photographic processes that ever was discovered or invented; and now it is a lost art. No one practises it, and I don’t think that there are half-a-dozen men living—myself included—that could at this day go through all the manipulations necessary to produce a good Daguerreotype portrait or picture; yet, when the process was at the height of its popularity, a great number of people pursued it as a profession in all parts of the civilized world, and in the United States of America alone it was estimated in 1854 that there were not less than thirty thousand people making their living as Daguerreans. Few, if any, of the photographers of to-day—whether amateur or professional—know anything of the forms or uses of plates, buffs, lathes, sensitising or developing boxes, gilding stands, or other Daguerreotype appliances; and I am quite certain that there is not a dealer in all England that can furnish at this date a complete set of Daguerreotype apparatus.