полная версия

полная версияHow to Make an Index

The following remarks will apply with equal force to a more general and universal index than that of the law:

"The preparation of a digest either of the whole or of any branch of the law is work of a very peculiar kind. It is one of the few literary undertakings in which a number of persons can really and effectively work together. Any given subject may, it is true, be dealt with in a variety of different ways; but when the general scheme, according to which it is to be treated, has been determined on, when the skeleton of the book has been drawn out, plenty of persons might be found to do the work of filling up the details, though that work is very far from being easy or matter of routine."

The value of analytical or index work is set in a very strong light by an observation of Sir James Stephen respecting the early digesters of the law. The origin of English law is to be found in the year-books and other series of old reports, which from the language used in them and the black-letter printing with its contractions, etc., are practically inaccessible. Lord Chief Justice Coke and others who reduced these books into form are in consequence treated as ultimate authorities, although the almost worshipped Coke is said by Sir James to be "one of the most confused, pedantic, and inaccurate of men."

A good index is that to the Works of Jeremy Bentham, published in 1843 under the dictation of Sir John Bowring. The Analytical Index to the Works of Jeremy Bentham and to the Memoirs and Correspondence was compiled by J. H. Burton, to whom it does great credit. The indexer prefixed a sensible note, where he writes:

"In some instances it would have been impossible to convey a notion of the train of reasoning followed by the author, without using his own words, and in these no attempt has been made to do more than indicate the place where the subject is discussed. In other cases where it has appeared to the compiler that an intelligible analysis has been made, he may have failed in his necessarily abbreviated sentences in embodying the meaning of the original, but defects of this description are indigenous to Indexes in general."

But here all is utility, and it is to the literary index that we turn for pleasure as well as instruction.

The index to Ruskin's Fors Clavigera, vols. 1-8 (1887), is a most interesting book, especially to Ruskin admirers. There are some specially delightful original and characteristic references under the heading of London, such as the following:

"London, Fifty square miles outside of, demoralised by upper classes

–– Its middle classes compare unfavourably with apes

–– Some blue sky in, still

–– Hospital named after Christ's native village in,

–– Honestest journal of, Punch.

–– crossings, what would they be without benevolent police?"

The index is well made and the references are full of life and charm, but the whole is spoilt by the bad arrangement. The entries are set out in single lines under the headings in the successive order of the pages. This looks unsystematic, as they ought to be arranged in alphabet. When the references are given in the order of the pages they should be printed in block.

There are several entries commencing with "'s"; thus, under

"St. George."

p. 386:

"'s war

"of Hanover Square."

p. 387:

"'s Square

's, Hanover Square"

p. 389:

"'s law

's school

's message

's Chapel at Venice."

In long headings that occupy separate pages these are repeated at the top of the page, but the headings are not sufficiently full: thus the saints are arranged in alphabet under S; George commences on page 386. On

p. 387:

"Saint—Saints continued

story of,"

p. 388:

"what of gold etc. he thinks good for people, they shall have"

p. 389:

"tenth part of fortunes for"

p. 390:

"his creed"

p. 391:

"loss of a good girl for his work"

In the case of all the references on these pages you have to go back to page 386 to find out to whom they refer.

There is a particularly bad block of references filling half a page under Lord.

"Lord, High Chancellor, 7.6; 's Prayer vital to a nation, 7.22; Mayor and Corporation, &c of Hosts."

It is a pity that an interesting index should be thus marred by bad arrangement.

Dr. Birkbeck Hill's complete index to his admirable edition of Boswell's Life of Johnson is a delightful companion to the work, and may be considered as a model of what an index should be; for compilation, arrangement, and printing all are good. Under the different headings are capital abstracts in blocks. There are sub-headings in alphabet under the main heading Johnson.

A charming appendix to the index consists of "Dicta Philosophi: A Concordance of Johnson's Sayings."

Dr. Hill writes in his preface:

"In my Index, which has cost me many months' heavy work, 'while I bore burdens with dull patience and beat the track of the alphabet with sluggish resolution,' I have, I hope, shown that I am not unmindful of all that I owe to men of letters. To the dead we cannot pay the debt of gratitude that is their due. Some relief is obtained from its burthen, if we in our turn make the men of our own generation debtors to us. The plan on which my Index is made, will I trust be found convenient. By the alphabetical arrangement in the separate entries of each article the reader, I venture to think, will be greatly facilitated in his researches. Certain subjects I have thought it best to form into groups. Under America, France, Ireland, London, Oxford, Paris and Scotland, are gathered together almost all the references to those subjects. The provincial towns of France, however, by some mistake I did not include in the general article. One important but intentional omission I must justify. In the case of the quotations in which my notes abound I have not thought it needful in the Index to refer to the book unless the eminence of the author required a separate and a second entry. My labour would have been increased beyond all endurance and my Index have been swollen almost into a monstrosity had I always referred to the book as well as to the matter which was contained in the passage that I extracted. Though in such a variety of subjects there must be many omissions, yet I shall be greatly disappointed if actual errors are discovered. Every entry I have made myself, and every entry I have verified in the proof sheets, not by comparing it with my manuscript, but by turning to the reference in the printed volumes. Some indulgence nevertheless may well be claimed and granted. If Homer at times nods, an index maker may be pardoned, should he in the fourth or fifth month of his task at the end of a day of eight hours' work grow drowsy. May I fondly hope that to the maker of so large an index will be extended the gratitude which Lord Bolingbroke says was once shown to lexicographers? 'I approve,' writes his lordship, 'the devotion of a studious man at Christ Church, who was overheard in his oratory entering into a detail with God, and acknowledging the divine goodness in furnishing the world with makers of dictionaries.'"

It is impossible to speak too highly of Dr. Hill's indexes to Boswell's Life of Johnson and Boswell's Letters and Johnson Miscellanies. Not only are they good indexes in themselves, but an indescribable literary air breathes over every page, and gives distinction to the whole. The index volume of the Life is by no means the least interesting of the set, and one instinctively thinks of the once celebrated Spaniard quoted by the great bibliographer Antonio—that the index of a book should be made by the author, even if the book itself were written by some one else.

The very excellence of this index has been used as a cause of complaint against its compiler. It has been said that everything that is known of Johnson can be found in the index, and therefore that the man who uses it is able to pose as a student, appearing to know as much as he who knows his Boswell by heart; but this is somewhat of a joke, for no useful information can be gained unless the book to which the index refers is searched, and he who honestly searches ceases to be a smatterer. It is absurd to deprive earnest readers of a useful help lest reviewers and smatterers misuse it.

Boswell himself made the original index to the Life of Johnson, which has several characteristic signs of its origin. Mr. Percy Fitzgerald, in his edition (1874), reprints the original "Table of Contents to the Life of Johnson," with this note:

"This is Mr. Boswell's own Index, the paging being altered to suit the present edition; and the reader will see that it bears signs of having been prepared by Mr. Boswell himself. In the second edition he made various additions, as well as alterations, which are characteristic in their way. Thus, 'Lord Bute' is changed into 'the Earl of Bute,' and 'Francis Barber' into 'Mr. Francis Barber.' After Mrs. Macaulay's name he added, 'Johnson's acute and unanswerable refutation of her levelling reveries'; and after that of Hawkins he put 'contradicted and corrected.' There are also various little compliments introduced where previously he had merely given the name. Such as 'Temple, Mr., the author's old and most intimate friend'; 'Vilette, Reverend Mr., his just claims on the publick'; 'Smith, Captain, his attention to Johnson at Warley Camp'; 'Somerville, Mr., the authour's warm and grateful remembrance of him'; 'Hall, General, his politeness to Johnson at Warley Camp'; 'Heberden, Dr., his kind attendance on Johnson.' On the other hand, Lord Eliot's 'politeness to Johnson' which stands in the first edition, is cut down in the second to the bald 'Eliot, Lord'; while 'Loughborough, Lord, his talents and great good fortune,' may have seemed a little offensive, and was expunged. The Literary Club was reverentially put in capitals. There are also such odd entries as 'Brutus, a ruffian,' &c."

One wishes that there were more indexes like Dr. Hill's in the world; and since I made an index to Shelley's works, I have often thought that a series of indexes of great authors would be of inestimable value.

First, all the author's works should be indexed, then his biographies, and lastly the anecdotes and notices in reviews and other books. How valuable would such books be in the study of our greatest poets! The plan is quite possible of attainment, and the indexes would be entertaining in themselves if made fairly full.

It is not possible to refer to all the good indexes that have been produced, for they are too numerous. A very remarkable index is that of the publications of the Parker Society by Henry Gough, which contains a great mass of valuable information presented in a handy form. It is the only volume issued by the society which is sought after, as the books themselves are a drug in the market. Mr. Gough was employed to make an index to the publications of the Camden Society, which would have been of still more value on account of the much greater interest of the books indexed; but the expense of printing the index was too great for the funds of the society, and it had to be abandoned, to the great loss of the literary world. Most of the archæological societies, commencing with the Society of Antiquaries, have issued excellent indexes, and the scientific societies also have produced indexes of varying merit.

The esteem in which the indexes of Notes and Queries are held is evidenced by the high prices they realise when they occur for sale. Mr. Tedder's full indexes to the Reports of the Conference of Librarians and the Library Association may also be mentioned.

A very striking instance of the great value which a general index of a book may possess as a distinct work can be seen in the "Index to the first ten volumes of Book Prices Current (1887-1896), constituting a reference list of subjects and incidentally a key to Anonymous and Pseudonymous Literature, London, 1901."

Here, in one alphabet, is a brief bibliography of the books sold in ten years well set out, and the dates of the distinctive editions clearly indicated. The compilation of this index must have been a specially laborious work, and does great credit to William Jaggard, of Liverpool, the compiler.

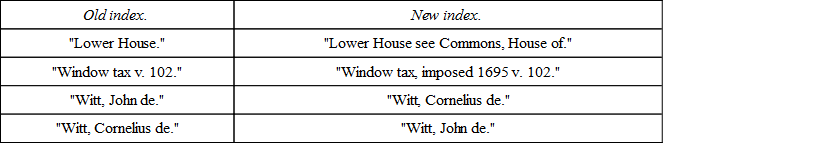

The authorities of the Clarendon Press, Oxford, are to be highly commended for their conduct in respect to the index to Ranke's History of England. This was attached to the sixth volume of the work published in 1875. It is by no means a bad index in itself; but a revised index was issued in 1897, which is a greatly improved edition by the addition of dates and fuller descriptions and Christian names and titles to the persons mentioned. The new index is substantially the same as the old one, but the reviser has gone carefully through it, improving it at all points, by which means it was extended over an additional twenty-three pages. It is instructive to compare the two editions. Four references as they appear in the two will show the improvement:

Miss Hetherington has very justly explained the cause of bad indexing. She says that it has been stated in the Review of Reviews that the indexer is born, not made, and that the present writer said: "An ideal indexer needs many qualifications; but unlike the poet he is not born, but made!" She then adds to these differing opinions: "More truly he is born and made."

I agree to the correction and forswear my former heresy. Certainly the indexer requires to be born with some of the necessary qualities innate in him, and then he requires to have those qualities turned to a practical point by the study of good examples, so as to know what to follow and what to avoid. Miss Hetherington goes on to say:

"As a matter of fact, people without the first necessary qualifications, or any aptitude whatever for the work are set to compile indexes, and the work is regarded as nothing more than purely mechanical copying that any hack may do. So long as indexing and cataloguing are treated with contempt rather than as arts not to be acquired in a day, or perhaps a year, and so long as authors and their readers are indifferent to good work, will worthless indexing continue."16

What, then, are the chief characteristics that are required to form a good indexer? I think they may be stated under five headings:

1. Common-sense.

2. Insight into the meaning of the author.

3. Power of analysis.

4. Common feeling with the consulter and insight into his mind, so that the indexer may put the references he has drawn from the book under headings where they are most likely to be sought.

5. General knowledge, with the power of overcoming difficulties.

The ignorant man cannot make a good index. The indexer will find that his miscellaneous knowledge is sure to come in useful, and that which he might doubt would ever be used by him will be found to be helpful when least expected. It may seem absurd to make out that the good indexer should be a sort of Admirable Crichton. There can be no doubt, however, that he requires a certain amount of knowledge; and the good cataloguer and indexer, without knowing everything, will be found to possess a keen sense of knowledge.

As I owe all my interest in bibliography and indexing to him, I may perhaps be allowed to introduce the name of my elder brother, the late Mr. B. R. Wheatley, a Vice-President of the Library Association, as that of a good indexer. He devoted his best efforts to the advancement of bibliography. When fresh from school he commenced his career by making the catalogue of one of the parts of the great Heber Catalogue. He planned and made one of the earliest of indexes to a library catalogue—that of the Athenæum Club. He made one of the best of indexes to the transactions of a society in that of the Statistical Society, which he followed by indexes of the Transactions of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society, Clinical, and other societies. He also made an admirable index to Tooke's History of Prices—a work of great labour, which met with the high approval of the authors, Thomas Tooke and William Newmarch.

CHAPTER V.

Different Classes of Indexes

"Of all your talents you are a most amazing man at Indexes. What a flag too, do you hang out at the stern! You must certainly persuade people that the book overflows with matter, which (to speak the truth) is but thinly spread. But I know all this is fair in trade, and you have a right to expect that the publick should purchase freely when you reduce the whole book into an epitome for their benefit; I shall read the index with pleasure."—William Clarke to William Bowyer, Nichols's Literary Anecdotes, vol. 3, p. 46.

IN dealing with the art of the indexer it is most important to consider the different classes of indexes. There are simple indexes, such as those of names and places, which only require care and proper alphabetical arrangement. The makers of these often plume themselves upon their work; but they must remember that the making of these indexes can only be ranked as belonging to the lowest rung of the index ladder.

The easiest books to index are those coming within the classes of History, Travel, Topography, and generally those that deal almost entirely with facts. The indexing of these is largely a mechanical operation, and only requires care and judgment. Verbal indexes and concordances are fairly easy when the plan is settled; but they are often works of great labour, and the compilers deserve great credit for their perseverance. John Marbeck stands at the head of this body of indefatigable workers who have placed the world under the greatest obligations. He was the first to publish a concordance of the Bible,17 to be followed nearly two centuries later by the work of Alexander Cruden, whose name has almost become a synonym for a concordance. After the Bible come the works of Shakespeare, indexed by Samuel Ayscough (1790), Francis Twiss (1805), Mrs. Cowden Clarke (1845), and Mr. John Bartlett, who published in 1894 a still fuller concordance than that of Mrs. Clarke. It is a vast quarto volume of 1,910 pages in double columns, and represents an enormous amount of self-denying labour. Dr. Alexander Schmidt's Shakespeare Lexicon (1874) is something more than a concordance, for it is a dictionary as well.

A dictionary is an index of words. We do not mention dictionaries in this connection to insist on the fact that they are indexes of words, but rather to point out that a dictionary such as those of Liddell and Scott, Littré, Murray, and Bradley, reaches the high watermark of index work, and so the ordinary indexer is able to claim that he belongs to the same class as the producers of such masterpieces as these.

Scientific books are the most difficult to index; but here there is a difference between the science of fact and the science of thought, the latter being the most difficult to deal with. The indexing of books of logic and ethics will call forth all the powers of the indexer and show his capabilities; but what we call the science of fact contains opinions as well as facts, and some branches of political economy are subjects by no means easy to index.

Some authors indicate their line of reasoning by the compilation of headings. This is a great help to the indexer; but if the author does not present such headings, the indexer has to make them himself, and he therefore needs the abilities of the précis-writer.

There are indexes of Books, of Transactions, Periodicals, etc., and indexes of Catalogues. Each of these classes demands a different method. A book must be thoroughly indexed; but the index of Journals and Transactions may be confined to the titles of the papers and articles. It is, however, better to index the contents of the essays as well as their titles.

Before the indexer commences his work he must consider whether his index is to be full or short. Sometimes it is not necessary to adopt the full index—frequently it is too expensive a luxury for publisher or author; but the short index can be done well if necessary.

Whatever plan is followed, the indexer must use his judgment. This ought to be the marked characteristic of the good indexer. The bad indexer is entirely without this great gift.

While trying to be complete, the indexer must reject the trivial; and this is not always easy. He must not follow in the steps of the lady who confessed that she only indexed those points which specially interested her. We have fair warning of incompleteness in The Register of Corpus Christi Guild, York, published by the Surtees Society in 1872, where we read, on page 321:

"This Index contains the names of all persons mentioned in the appendix and foot-notes, but a selection only is given of those who were admitted into the Guild or enrolled in the Obituary."

The plan here adopted is not to be commended, for it is clear that so important a name-list as this is should be thoroughly indexed. However learned and judicious an editor may be, we do not choose to submit to his judgment in the offhand decision of what is and what is not important.

There is a considerable difference in the choice of headings for a general or special index—say, for instance, in indexing electrical subjects the headings would differ greatly in the indexes of the Institution of Civil Engineers or of the Institution of Electrical Engineers. In the former, dynamos, transformers, secondary or storage batteries, alternate and continuous currents would probably be grouped under the general heading of Electricity, while in the latter we shall find Dynamos under D, Transformers under T, Batteries under B, Alternate under A, and Continuous under C.

The indexes to catalogues of libraries, etc., are among the most difficult of indexes to compile. It was not usual to attach an index of subjects to a catalogue of authors until late years, and that to the Catalogue of the Athenæum Club Library (1851) is an early specimen. The New York State Library Catalogue (1856) has an index, as have those of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society (1860) and the London Library (1865 and 1875). That appended to the Catalogue of the Manchester Free Library (1864) is more a short list of titles than an index.

There are special difficulties attendant on the indexing of catalogues. Books are written in many languages, and there is considerable trouble in bringing together the books on a given subject produced in many countries. The titles of books are not drawn up on the same system or with any wish to help the indexer. Titles are seldom straightforward, for they are largely concocted to attract the readers, without any honest wish to express correctly the nature of the contents of the book. They are usually either too short or too enigmatical. The titles of pamphlets, again, are often too long; and it may be taken as an axiom that the longer the title the less important the book.

The indexer, however, has a great advantage over the cataloguer, because the latter is bound by bibliographical etiquette not to alter the title of a book, while the indexer is at liberty to alter the title as he likes, so as to bring together books on the same subject, however different the titles may be. Herein consists the great objection to the index composed of short titles, as in Dr. Crestadoro's Index to the Manchester Free Library Catalogue. Books almost entirely alike in subject are separated by reason of the different wording of the titles. It is much more convenient to gather together under one entry books identical in subject, and there is no utility in separating an "elementary treatise" on electricity from "the elements" of electricity. One important point connected with indexes to catalogues is to add the date of the book after the name of the author, so that the seeker may know whether the book is old or new.

An index ought not to supersede the table of contents, as this is often useful for those who cannot find what they want in the index, from having forgotten the point of the heading under which it would most likely appear in the alphabet.

In the year 1900 there was a controversy in The Times on a proposed subject index to the catalogue of the library of the British Museum. It was commenced on October 15th by a letter signed "A Scholar," and closed on November 19th by the same writer, who summed up the whole controversy. "A Scholar" expressed himself strongly against the proposal, and as he himself confesses he used very arrogant language. In consequence of which, most readers must have desired to find him proved to be in the wrong. This desire was satisfied when Mr. Fortescue, the keeper of the printed books at the British Museum, delivered his address as President of the Library Association on August 27th last.