полная версия

полная версияSpain

But we must hurry on. With the downfall of Granada, the discovery of America, the consolidation of the kingdoms of the Peninsula into one nation, real historical study began in Spain. Thus we have in quick succession many works of considerable merit, such as the "Annals of Aragon," by Zurita (1512-80); the "Comunidades of Castille," by Mejia (1549); the great "History of Spain," by the Jesuit Mariana (1536-1632); Herrera's "General History of the Indies" (1549-1625); the "Commentaries on Peru," by the Inca, Garcilasso de la Vega (1540-1616); the monographs of Hurtado de Mendoza on the "Wars of Granada" (1610); the "Expedition of the Catalans," by Moncada (1623); the "Wars of Catalonia," by Melo (1645); and, in literary form superior to all these, the "Conquest of Mexico," by Solis (1685).

Of poetry, apart from the stage and from the romances, there is not much of real value to engage our attention. The grandest verses of early Spain are undoubtedly the "Coplas" of Manrique (1476), which have been often translated into English, and which form one of the finest elegies extant in any language. After Garcilassa de la Vega (1503-36), Spanish poets fell into an unworthy imitation of the Italian; and subsequently Gongora (1561-1627) set the example of a still more debased and stilted style, full of affected conceits and mistaken classicalism. The only tolerable epic poem which Spain has yet produced is the "Araucana" of Ercilla, which tells the story of the wars with Indians of that name in Chili, and in which the author had personally taken part.

From the close of the seventeenth and through the greater part of the eighteenth century, literature partook of the progressive decadence of all things in Spain. It withered and declined under the double censure and oppression of the king and of the inquisition. The theatre, which had striven hard in Spain to become the ally, or even the handmaid, of the Church, was contemptuously thrust aside by the latter, and within a century of Calderon's death, not even an Infanta could procure permission from the inquisition for a comedy in time of carnaval. No history of any value could be written under such conditions; the only outlet for literary skill lay in religious and mystic writings, which are of singular beauty. The classical and grammatical movement of the Renaissance which had begun so well under the patronage of Juan de Cisneros, Cardinal Ximenes, the great minister of Charles V., and the chief monument of which is the Complutensian Polyglot Bible of 1514-17, and its greatest scholar, Antonio de Nebrija, soon died away, and the Spanish universities, which for a while had been the admiration, became, in the eighteenth century, the laughing-stock of Europe. Of the earlier period we may mention among the religious writers Luis de Granada (1505-68), Santa Teresa (1515-82), the Jesuit, Ribadeneyra (1527-1611), Juan de la Cruz (1542-91); but even this literature degenerated into casuistry and mere technical scholasticism. Spanish religious poetry is, however, far more copious and of greater excellence than is generally supposed. It has been studied and collected in our own day by the opposite schools of the Spanish Protestants, and by the champion of orthodoxy, Menendez Pelayo.

There is little to notice in Spanish literature from this time until the rise of the doctrinaire and economical writers of the reign of Carlos III., who for the most part closely followed the contemporary school of French publicists and encyclopædists. Among these are Padre Benito Feyjoo, who was the first to protest against the absence of science and true learning in Spain; the Padre Isla (1703-81), decidedly one of the wittiest of Spanish writers and satirists; Jovellanos (1744-1811), the best statesman and political writer of his time, and in the purer walks of literature the two Moratins (1737-1828). One or two philological works, far in advance of their age, made now their appearance, such as the tracts of Padre Sarmiento (1692-1770) on the Spanish language; the works of the Jesuits Larramendi (1728-45) on the Basque, and of Hervas (1735-1805) on general philology. To this period also belongs the magnificent collection entitled, "La España Sagrada," commenced by Florez (1754-1801), and, after many interruptions, completed only in 1880.

Towards the close of the eighteenth century, however, a reaction set in against the French and so-called classical school, and the attention of Spanish writers was recalled to the masterpieces of their own earlier literature. The movement was accelerated by the course of political events, and the successes of the war of independence against the French. One of the earliest defenders of the romantic against the classical school was Bohl de Faber, a Hamburg merchant settled in Cadiz. He published in 1820-3, in his native town, selections from works of the early poets and dramatists of Spain; and his daughter, Cecilia, under the name of Fernan Caballero, has attained the highest rank among the lady novelists of Spain. The admission of Bohl de Faber into the ranks of the Spanish Academy, under Martinez de la Rosa, marks the definite triumph of the national school. At first it seemed as if the movement would produce simply a change of French for English and German models. Fiction became a stiff imitation of Sir Walter Scott. In poetry the influence of Byron reigned supreme. Espronceda (1810-42) has equalled his master in his cynical odes. "The Beggar," "The Executioner," "The last day of the Condemned," and "The Pirate," might almost have been penned by Byron; and "El Mundo Diablo" will long live in Spanish literature. Zorilla, born in 1817, still living, has been more successful in his dramas than Espronceda, especially in "Don Juan Tenorio," but his poems are inferior in force, though rich in colouring and in the melody of his verse. Gustavo Becquer (1836-70) is another poet who fed his genius with the legends of the past, but his models were Edgar Poe and Hoffmann; some of his weird fantastic tales and poems are excellent examples of their kind. Of an opposite character are the realistic novels of Fernan Caballero above mentioned (1797-1877). These are exquisite rose-tinted photographs of Spanish life and character taken by one who sees everything Spanish with a favourable eye. Her writings are distinguished by a delicate aristocratic grace and tenderness which she throws over all subjects which she handles, whether of high or lowly life. As an artist her plots are inferior to those of many worse novelists; her descriptions of scenery are beautiful and exact; as a delineator of individual character she fails, but as a painter of type and class she is unrivalled. Her sketches abound in humour and in gentle melancholy; a deep and true religious feeling pervades every line, but she fails in strength and passion. Thus she can be classed only in the second rank of female novelists, and does not approach the genius of Georges Sand or of George Elliot. Trueba, in the north, essays to imitate her, but he often sinks into puerility, nor are his studies marked by the conscientious regard for fact which distinguishes those of the lady writer. Pereda, who delineates the peasants of Santander, is a less prolific writer but of higher literary merit. Of living novelists we should place in the first rank Juan Valera with his powerful novels, "Pepita Jimenez," "El Doctor Faustino," and "Doña Luz." Next to him is, perhaps, Perez Galdos, who, in the series entitled "Episodios Nacionales," rivals the national romances of Erckmann-Chatrian in French. Pedro Alarcon has a greater fund of wit and humour, and his "Sombrero de tres picos" is a most mirth-provoking tale. Fernandez y Gonzalez, in the number, if not in the quality of his works, may almost compete with the elder Alexandre Dumas, whose semi-historical style he repeats. Feliz Pizcueta, a Valencian writer, has also written many novels, whose scenes are laid in his native province. Among dramatists now living, or lately dead, we may mention Hartzenbusch (1806-80), whose "Amantes de Teruel" is one of the most successful tragedies of the romantic school; Breton de los Herreros (1800-70); Gertrudis de Avellaneda, the first Spanish female dramatist, born in Cuba in 1816; Gutierrez, who, born in 1813, sought refuge, like Zorilla, in Spanish America; Lopez de Ayala; and lastly, J. Estebanez, whose best work is entitled "Un Drama Nuevo," and who reaches a high level of dramatic art. Of more extravagant style, inferior to these, and already marking a decadence, is José Echegaray, a man of most versatile and opposite talents, and one of the first mathematicians of Spain, the best of whose plays is "Locura o Santidad." Of lyric poets we may mention Campoamor, an original but languid and graceful writer of minor verse, and Selgas, whose grace is seasoned with wit and satire, but whose prose is much superior to his verse. But by far the greatest of living Spanish poets, though like Tennyson he has failed comparatively on the stage, is Gaspar Nuñez de Arce. His "Gritos del Combate," and "La Ultima Lamentacion de Lord Byron," contain some noble verses. He writes in the spirit of purest patriotism, with a stern morality, and with severe and chastened art.

But more important than in the movement of fiction and poetry has been the influence of the romantic school in history. The attention of Spaniards has been at length turned to the study of their original records, and especially to that of the early Arabic writers. The first to attempt this, but with insufficient means, was J. A. Condé (1757-1820) in his "Historia de la Dominacion de los Arabes en España." This has since been superseded by the exacter learning of Don Pascual Gayangos, in the "Mohammedan Dynasties of Spain," by many foreign writers, and by the labours of Fernandez y Gonzalez in "Los Mudejares de Castilla" (1866) and others. The labours of Don Modeste and Don Vicente Lafuente, the one in ecclesiastical, the other in civil history, must be mentioned with approval, and the works of Amador de los Rios, on the literature of Spain and on the history of the Jews in Spain, do honour to his country. Among other historians, we may mention F. Castro and Sales y Ferrer, whose works are the popular manuals in education. Fernandez Guerra in the ancient, and Coello in the modern, Geography of Spain, are authors of the highest class; nor must we omit the Englishman Bowles, who wrote on the Natural History of Spain in 1775. In Geology another English name, Macpherson, attains the highest rank, together with the surveyors employed on the "Comision de la Mapa Geologica" of Spain. On the history of property in Spain and Europe, are two remarkable essays by Cárdenas and de Azcárate. In theology, on the Roman Catholic side, are the writings of Balmés (1810-48); of Doñoso Cortes (1809-53), of the present Bishop of Cordova, Ceferino Gonzalez; and, still publishing, the remarkable production of Menendez Pelayo, "Historia de los Heterodoxos in España;" while in the Protestant theology, Usoz, assisted by B. Wiffen in England and Boehmer in Germany, has rescued from oblivion the works of the Spanish reformers. In philology the Jesuit, Padre Fita y Colomé, worthily continues the traditions of Larramendi and of Hervas. Fernandez Guerra, and F. Tubino, and the Barcelona school pursue archæological studies with success. The influence of outside European thought is every day more evident in Spain. Ardent disciples of the school of Comte, of Darwin, and of Schopenhauer, are to be found among her publicists. In political economy Figuerola, G. Rodriguez, Colmeiro, Azcárate, and others, follow keenly the teaching of the English liberal school. Face to face in parliamentary eloquence and in politics stand Cánovas del Castello and Emilio Castelar; the latter distinguished by a florid oratory which is unsurpassed in Europe, but whose style is far more effective when spoken than when read; the former, with greater learning and a more cultivated taste, would undoubtedly be known as a writer but for his devotion to political life. The periodical and daily press of Spain, though not to compare with that of England, or of the United States, is almost on a par with that of most continental countries; the scientific and literary reviews and magazines are yearly increasing both in numbers and in value.

This sketch, however brief, would be incomplete without a glance at what may be called the provincial literature of Spain. The publishers of Barcelona, especially in illustrated works, vie with those of Madrid. It is not in the Castilian tongue alone that the awakening is apparent. In Catalonia and in Valencia the study of the native idiom and of their ancient authors has been taken up with zeal, and with happiest results in history and philology. Victor Balaguer, the Catalan poet and dramatist is equal to all contemporary Spanish poets save Nuñez de Arce. The dramas of Pablo Soler (Serafi Petarra) are received with an enthusiasm unknown to audiences in Madrid. Mila y Fontanals, Bofarull, and Sanpére y Miquel are investigating with success the language, history, and archæology of their country. A like, though necessarily a less important, movement is taking place in Andalusia, in the Basque Provinces, in the Asturias, and in Galicia; everywhere what is worth preserving in these dialects is being sought out, edited, and given to the press. The archives of Simancas are at length thrown open to the world, and guides and catalogues are being industriously prepared. Sevillian scholars are also studying the archives of the Indies, and the treasures of Hebrew and Arabian lore.

Thus, if Spain can at present boast no writer whom we can place undoubtedly and unreservedly in the very first rank, she shows an intellectual movement which, though confined at present to a comparatively small portion of her inhabitants, may, if it spread and continue, place her again in her proud position of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as one of the first of European nations, not perhaps in arms and power, but in literature, if not in science.

CHAPTER IX.

EPILOGUE

A FEW words in conclusion. Spain is far from being a worn-out country. On the contrary, both in the character and capacities of its varied populations, in the mineral riches of its soil, in its agricultural wealth, in industrial resources, and in the artistic taste of its workmen, it is capable of vast development.

Two things hinder this, and will probably hinder it for some time. These are the political separation of Spain and Portugal, so ill-adapted to the geographical conformation of the Peninsula. The great rivers of Spain run westward, but the benefit of these fluvial highways is entirely lost to the country through the intercalation of Portugal into the western sea-board, thus making useless to Spain her natural system of river transport, and cutting her off from her best and most direct Atlantic ports. It is Lisbon, and not Madrid, which should be the capital of the whole Peninsula. Scarcely less an evil to Spain is the possession of Gibraltar by the English, which, besides the expense of watching the fortress, and the loss to Spain of the advantage of the possession of the great port of call for the whole maritime traffic of the East, is a school of smuggling and contraband, and a focus of corruption for the whole of South-western Spain. Were the whole Atlantic and Mediterranean sea-board in sole possession of one nation, the expenses of the custom-house would be greatly lessened, while the smuggling on the Portuguese and British frontiers would wholly disappear. In no point was the effect of the narrow and jealous policy of Philip II. more disastrous, than in his failure even to attempt to attach the Portuguese to his rule when the kingdoms were temporarily united under his crown.

The second evil, and one of still graver proportions, is that of the exceedingly corrupt administration of the central government, and of almost every branch of public employment. It is difficult to exaggerate this mischief. It is not bad external political government, it is not a faulty constitution, but it is an administration in which corruption has become a tradition and the rule, that is the real evil in Spain. It is this which baffles every ministry that tries to do real good. Only a ministry, or succession of ministries, composed of men of thorough honesty, of iron will, and of competence in financial administration, supported by strong majorities, can hope to deal with this gigantic growth. Even then it must be a work of time. With an honest administration, and prudent and sagacious development of her resources, Spain would soon regain financial soundness and recover her place among the nations.

The contest between the opposite commercial systems of protection and free trade is not yet concluded, nor is likely to be, in Spain. As long as England, which has the greatest interest of any foreign power in the establishment of the latter system, maintains a tariff which unduly favours the wines of France in comparison with those of Spain free trade is not likely to be popular. From the varied character of her products, Spain is of all European countries naturally the most self-sufficing. Her north-western provinces furnish her with cattle in abundance; no finer wheat is grown than that on the central plateau, and it could easily be produced in quantity more than sufficient for her wants; wine, oil, and fruits she possesses in superfluity; even sugar is not wanting in the south; cotton, indeed, she has not; but wool of excellent quality is the produce of her numerous flocks, and it needs only the establishment of efficient manufactories for Spanish cloth and woollen stuffs to regain their ancient renown. All the most useful minerals abound, and are of the finest quality, especially the iron, and the development of the working of the Asturian and Andalusian coal-fields renders Spain yearly more and more independent of England in this respect. True it is that foreign capital is, and will for some time be necessary to assist in extracting this hidden wealth; but if the ordinary Spaniard of the educated classes, instead of seeking a bare, and too often a base, subsistence in petty government employment or in ill-paid professions—instead of seeking the barren honour of a university degree—would apply himself to scientific, industrial, or agricultural enterprise, he might soon obtain his legitimate share of the profits which now go mainly into the hands of foreign speculators and shareholders.

Spaniards are commonly said to be cruel and bloodthirsty, with little regard for the sufferings of others or respect for human life; and undoubtedly there is some truth in this charge, but it does not apply to the whole Peninsula. Many of Spain's best writers deplore it, and inveigh strongly against it and against the bull-fights, which, in their present form, are not more than a century old. As a national sport, the modern bull-ring, with its professional torreadors and its hideous horse-slaughtering, differs from the pastime in which Charles V. and his nobles used to take part as much as a prizefight from a tournament. The appeals of Fernan Caballero to the clergy, the efforts of Tubino, Lastre, and others to arouse the public against this wanton cruelty have hitherto been of no avail. We can only hope in the future. On the other hand, it is unjust to shut our eyes to the noble charities of Spain. She was the first to care for lunatics. Many of her hospitals and asylums for the aged were conducted with a tenderness and consideration unknown in other lands. Even a beggar is treated with respect, and is relieved without contumely. The treatment of her prisoners and the condition of her prisons, which was long so foul a blot, is now being efficiently removed; she is at least making an earnest effort to attain the level of European civilization in this respect.

Intellectually, in science, and especially in literature, Spain is advancing rapidly. The historical treasures long buried in the archives of Simancas, and those of the Indies at Seville, are now thrown open to the world, and are eagerly consulted by native historians. Her literary and scientific men, though comparatively few in number, are full of zeal and intelligence. There needs only a larger and more appreciative audience to encourage them in their labours in order to bring the literature of Spain to a level with that of any European country of equal population.

APPENDIX I

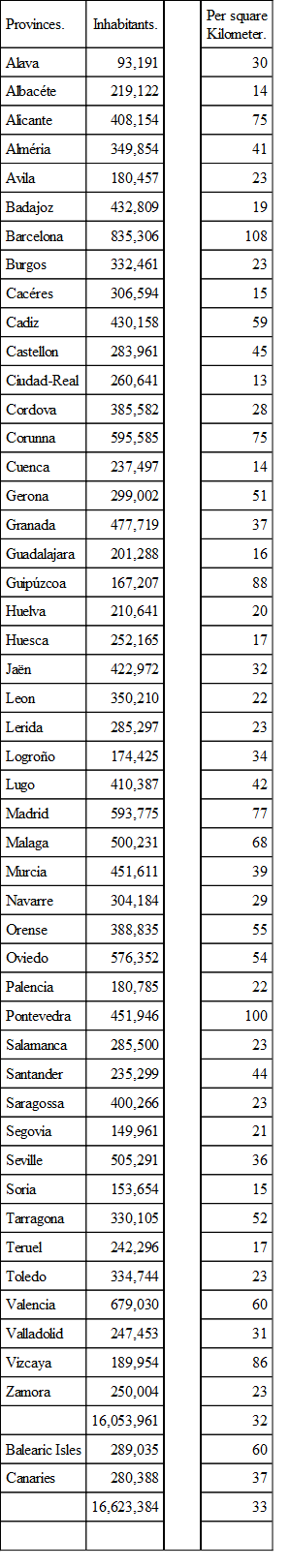

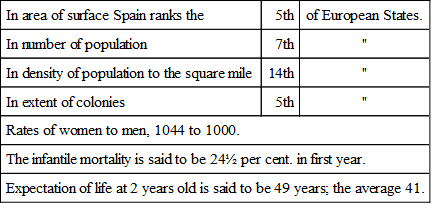

PROVINCES OF SPAIN AND THEIR POPULATION IN 1877.

APPENDIX II

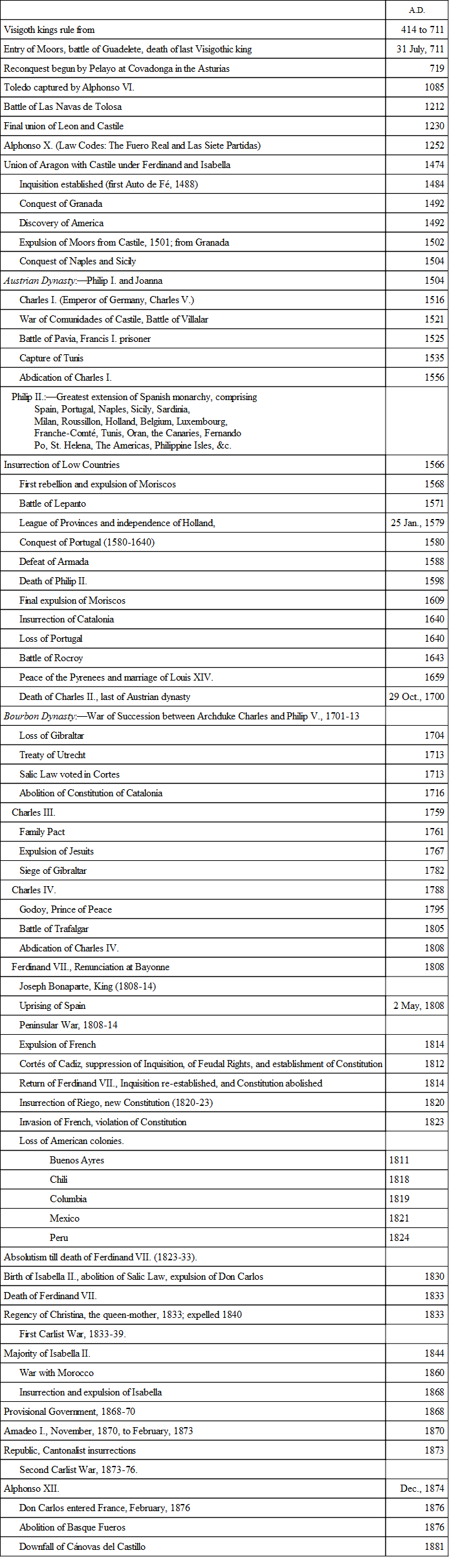

PRINCIPAL EVENTS OF SPANISH HISTORY.

APPENDIX III

LIST OF BOOKS CHIEFLY MADE USE OF IN THE FOREGOING PAGESGeography:—

La Nouvelle Géographie Universelle, par Elisée Reclus, series 5 and 6. Hachette, Paris, 1876.

Spanien und die Balearen. Willkomm, Berlin, 1879.

The Balearic Isles, by T. Bidwell. London.

Boletin de la Sociedad Geográfica de Madrid, various years.

Introduccion à la Historia Natural y à la Geográfica Fisica de España, por Don Guillermo Bowles. Madrid, 1775.

Espagne, Algerie, et Tunisie, par P. de Tchikatchef. Paris, 1880.

Libro de Agricultura, por Abu Zaccaria. Spanish translation Seville, 1878.

Meteorology:—

Reports of the Meteorological Society of Madrid, various years.

Revista Contemporanea, tomo xxx. 4. December, 1880.

Philology:—

Grammaire des Langues Romaines, par F. Diez, 2nd German edition. French translation, Paris.

Études sur les Idiomes Pyrénéenes, par A. Luchaire. Paris, 1879.

Various articles in Spanish Literary and Provincial Journals.

History, General:—

Dunham's History of Spain and Portugal, 5 vols. Lardner's Cabinet Encyclopaedia.

Resúmen de Historia de España, por F. de Castro, 12th edition. Madrid, 1878.

Compendio Razonado de História General, por Sales y Ferré, last edition, 4 vols. Madrid, 1880.

History of Civilization, by Buckle, 3 vols. London.

Particular Histories:—

Investigaciones sobre la História de España, por Dozy, Spanish translation, 2 vols. Seville, 1877.

Los Mudejares de Castillo, por Fernandez Gonzalez. Madrid, 1866.

Vida de la Princesa Eboli, by G. Muro, with introductory letter by Cánovas del Castillo. Madrid, 1877.

Text of various Fueros, and of the Constitutions since 1812.

Espagne Contemporaine, par F. Garrido. Bruxelles, 1865.

Ecclesiastical History:—

Die Kirchengeschichte von Spanien, von P. B. Gams, 5 vols. Berlin, 1879.

Historia de los Heterodoxos Españoles, por M. Menendez Pelayo, tomos i. and ii. (Tomo iii. not yet published.) Madrid, 1880.

History of Property, &c.:—

Ensayo sobre la História del derecho de Propiedad y su Estado actual en Europa, por G. de Azcárate. Tomos i. and ii. (Tomo iii. not yet published.) Madrid, 1879-80.

Estudios filosóficos y politicos, por G. de Azcárate. Madrid, 1877.

La Constitucion Inglesa y la politica del Continente, por G. de Azcárate. Madrid, 1878.

Ensayo sobre la Propiedad Territorial en España, per Cardénas, 2 vols. Madrid, 1875.

Art:—

Street's Gothic Architecture in Spain. Murray, 1865.

The Industrial Arts of Spain, by Juan F. Riaño. London 1879.

Discurso de Recepcion, by Juan F. Riaño. Madrid, 1880.

Numerous articles in Spanish Periodicals.

Literature:—

Ticknor's History of Spanish Literature, 4 vols. London, 1845.

Sismondi's Literature of the South of Europe. Bohn, London, 1846.

Hubbard's Littérature Contemporaine en Espagne. Paris, 1876.

Guide-Books:—

Ford's last edition, and O'Shea's Guide to Spain, with numerous Spanish general and local guides, and particular descriptions of towns, provinces, &c.

Tourist Books in Spanish, German, French, and English. The only ones needing mention, as going out of the common round are—

Untrodden Spain, by J. H. Rose. Bentley, 1875.

Among the Spanish People, by J. H. Rose. Bentley, 1877.

Government and Consular reports too numerous to specify; but we must except Phipps' masterly Report on Spanish Finance to the close of 1876.

1