полная версия

полная версияMaster Wace, His Chronicle of the Norman Conquest From the Roman De Rou

CHAPTER VII.

HOW WILLIAM PROSPERED, AND HOW HE WENT TO ENGLAND TO VISIT KING EDWARD; AND WHO GODWIN WAS

The story will be long ere it close, how William became a king, what honour he reached, and who held his lands after him. His acts, his sayings and adventures that we find written, are all worthy to be recounted; but we cannot tell the whole. In his land he set good laws; he maintained justice and peace firmly, wherever he could, for the poor people's sake, and he never loved the knave nor the company of the felon.

By advice of his baronage he took a wife99 of high lineage in Flanders, the daughter of count Baldwin, and the granddaughter of Robert king of France, being the daughter of his daughter Constance. Her name was Mahelt100, related to many a noble man, and very fair and graceful. The count gave her joyfully, with very rich appareillement, and brought her to the castle of Ou101, where the duke espoused her. From thence he took her to Roem, where she was greatly served and honoured.

At Caem the duke built two abbeys, endowing them richly. In the one, which was called SAINT STEPHEN, he placed monks; Mahelt his wife took charge of the other, which is that of THE HOLY TRINITY; she placed nuns there, and was buried in it as she had directed in her life, from the love which she had always used to bear towards it102.

And the duke did what, I believe, no one before or after did. He sent103 for all his bishops to assemble, with his earls, abbots, and priors, barons and rich vavassors, at Caem, there to hear his commandment; and caused the holy bodies, wherever he could find them, to be brought thither, whether from bishopric or abbey, over which he had seigniory. He had the body of St. Oain104 taken from Roem to Caem in a chest; and when the clergy, and the holy relics, and the barons, of whom there were many, were assembled on the appointed day, he made all swear on the relics to hold peace and maintain it from sunset on Wednesday to sunrise on Monday. This was called THE TRUCE, and the like of it I believe is not in any country. If any man should beat another meantime, or do him any mischief, or take any of his goods, he was to be excommunicated, and amerced nine livres to the bishop. This the duke established, and swore aloud to observe, and all the barons did the same; they swore to keep the peace and maintain the truce faithfully.

To commemorate this peace through all time, that it might endure for ever, they forthwith built a minster of hewed stone105 and mortar, on the spot where they swore upon the relics which had been brought to the council. Many who had assisted at founding the minster called it Toz-sainz106, on account of so many holy relics having been there; but it pleased many men to call it Sainte-paiz, on account of the peace sworn to when it was built: at least I have heard it called both Sainte-paiz and Toz-sainz. Close by they built a chapel called Saint-Oain's, on the spot where his bones had rested while the council sat.

William was generous, and the strangers who knew him, cherished him much. He was very gentle and courteous, therefore king Edward loved him well; great indeed was their love, each holding the other his lord. The duke went to see Edward and know his mind; and having crossed over into England107, Edward received him with great honour, and gave him many dogs and birds, and whatever other good and fair gifts he could find, that became a man of high degree. He did not tarry long, but returned into Normandy; for he was engaged with the Bretons, who were at that time disturbing him.

Godwin had great wealth in England; he was rich in lands, and carried himself proudly. Edward had his daughter to wife; but Godwin was fell and false, and brought many evils on the land; and Edward feared and hated him on account of his brother whom he had betrayed, and of the Normans whom he had decimated, and many other mischiefs plotted by him. And thus, both in words and deeds, great discord arose between them, which was never thoroughly healed. Edward feared Godwin much, and banished him from the land; swearing that he should never come back, or abide in his kingdom, unless he swore fealty to him, and delivered him hostages, and pledges for keeping the peace during his life. Godwin dared not refuse, and as well to satisfy the king, as for the sake of his relations, and the protection of his men, he delivered one of his nephews and one of his sons108 as hostages to the king. Edward sent them to Duke William in Normandy, as to one in whom he placed great trust, and desired him to keep them safe till he should himself demand them. This looked, people said, as if he wished William always to keep them, for the purpose of securing the kingdom to himself in case of Edward's death. On these terms the king suffered Godwin to remain at home in peace. I do not know how long this lasted, but I know that Godwin in the end choked himself, while eating at the king's table during a feast.

King Edward was debonaire; he neither wished nor did ill to any man; he was without pride or avarice, and desired strict justice to be done to all109. He endowed abbeys with fiefs, and divers goodly gifts, and Westminster in particular. Ye shall hear the reason why. On some occasion, whether of sickness or on the recovery of his kingdom, or on some escape from peril at sea, he had vowed a pilgrimage to Rome, there to say his prayers, and crave pardon for his sins; to speak with the apostle, and receive penance from him. So at the time he had appointed, he prepared for his journey; but the barons met together, and the bishops and the abbots conferred with each other, and they counselled him by no means to go. They said they feared he could not bear so great a labour; that the pilgrimage was too long, seeing his great age; that if he should go to Rome, and death or any other mischance should prevent his return, the loss of their king would be a great misfortune to them; and that they would send to the apostle110, and get him to grant absolution from the vow, so that he might be quit of it, even if some other penance should be imposed instead. Accordingly they sent to the apostle, and he absolved the king of his vow, but enjoined him by way of acquittance of it, to select some poor abbey dedicated to St. Peter, honoring and endowing it with so many goods and rents, that it might for all time to come be resorted to, and the name of St. Peter thereby exalted.

Edward received the injunction of the apostle in good part. On the western side of London, as still may be seen, there was an abbey of St. Peter, which had for a long time been greatly impoverished; it is situate on an island of the Thames called Zonee (Thorn-ee)111, so named because there were plenty of thorns upon it, and water around it; for the English call an island 'ee,' and what the French call 'espine' they call 'zon' (thorn); so that 'Zon-ee' (Thorn-ee) in English means 'isle d'espine' in French. The name of Westminster was given to it afterwards, when the minster was built King Edward perceived that there was much to improve at Westminster; he saw that the brotherhood were poor, and the minster decayed; and by counsel of clerks and laymen, while the country was in prosperity, he with great labour and attention, restored and amply endowed it with lands and other wealth. He gave indeed so much of his own, of fair villages, rich manors and lands, crosses and other goodly gifts, that the place will never know want, if things are managed honestly. But when each monk wants much service, is greedy of money, and makes a purse; the common stock soon wastes accordingly. Thus, however, the king restored Westminster, and held the spot dear, and loved it well. He also afterwards gave so much to St. Edmund (Bury), that the monks who dwell there are very rich.

King Edward was now of a good age; his reign had been long, and to his sorrow he had no child, and no near relation to take his kingdom after him, and maintain it. He considered with himself who should inherit it when he died; and often bethought him, and said he would give his inheritance to duke William his relation, as the best of his lineage. Robert his father had brought him up, and William himself had been of much service to him; and, in fact, all the good he had received had come from that line, and he had loved none so well, however kindly he might behave to any one else. For the honor thereof of his good kinsman, with whom he had been brought up, and on account of the great worth of William himself, he determined to make him heir to the realm.

CHAPTER VIII.

OF HAROLD'S JOURNEY TO NORMANDY, AND WHAT HE DID THERE

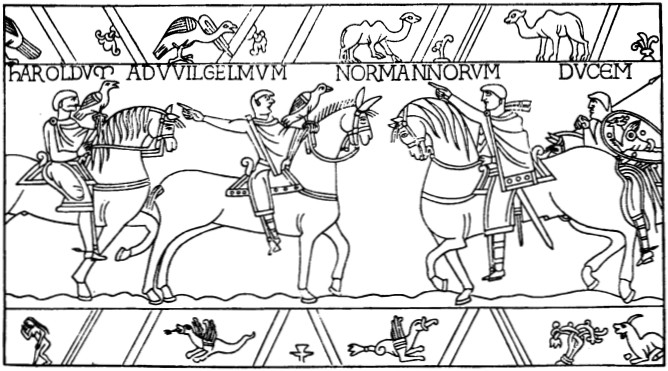

Now in that country of England there was a seneschal112, Heraut113 by name, a noble vassal, who on account of his worth and merits, had great influence, and was in truth the most powerful man in all the land. He was strong in his own men, and strong in his friends, and managed all England as a man does land of which he has the seneschalsy. On his father's side he was English, and on his mother's Danish; Gite114 his mother being a Danish woman, born and brought up in great wealth, a very gentle lady, the sister of King Kenut. She was wife to Godwin, mother to Harold, and her daughter Edif115 was queen. Harold himself was the favourite of his lord, who had his sister to wife. When his father had died (being choked at the feast), Harold, pitying the hostages, was desirous to cross over into Normandy, to bring them home. So he went to take leave116 of the king. But Edward strictly forbade him, and charged and conjured him not to go to Normandy, nor to speak with duke William; for he might soon be drawn into some snare, as the duke was very shrewd; and he told him, that if he wished to have the hostages home, he would choose some messenger for the purpose. So at least I have found the story written117. But another book tells me that the king ordered him to go, for the purpose of assuring duke William, his cousin, that he should have the realm after his death. How the matter really was I never knew, and I find it written both the one way and the other.

Whatever was the business he went upon, or whatever it was that he meant to do, Harold set out on his way, taking the risk of what might fall out. What is fated to happen no man can prevent, let him be who he will. What must be will come to pass, and no one can make it nought.

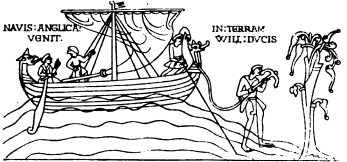

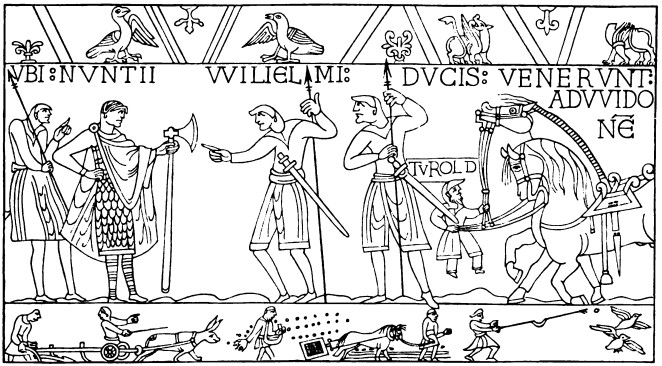

He made ready two ships, and took the sea at Bodeham118. I know not how the mischief was occasioned; whether the steersman erred, or whether it was that a storm arose; but this I know, that he missed the right course, and touched the coast of Pontif, where he could neither get away, nor conceal himself. A fisherman of that country, who had been in England and had often seen Harold, watched him; and knew him, both by his face and his speech; and went privily to Guy, the count of Pontif119, and would speak to no other; and he told the count how he could put a great prize in his way, if he would go with him; and that if he would give him only twenty livres, he should gain a hundred by it, for he would deliver him such a prisoner, as would pay a hundred livres or more for ranson. The count agreed to his terms, and then the fisherman showed him Harold. They seized and took him to Abbeville; but Harold contrived to send off a message privily to duke William in Normandy, and told him of his journey; how he had set out from England to visit him, but had missed the right port; and how the count of Pontif had seized him, and without any cause of offence had put him in prison: and he promised that if the duke would deliver him from his captivity, he would do whatever he wished in return.

Guy guarded Harold mean time with great care; fearing some mischance, he sent him to Belrem120, that he might be further from the duke. But William thought that if he could get Harold into his keeping, he might turn it to good account; so he made so many fair promises and offers to the earl, and so coaxed and flattered him, that he at last gave up his prisoner121; and the duke thus got possession of him, and gave in return to the count Guy a fair manor lying along the river Alne122.

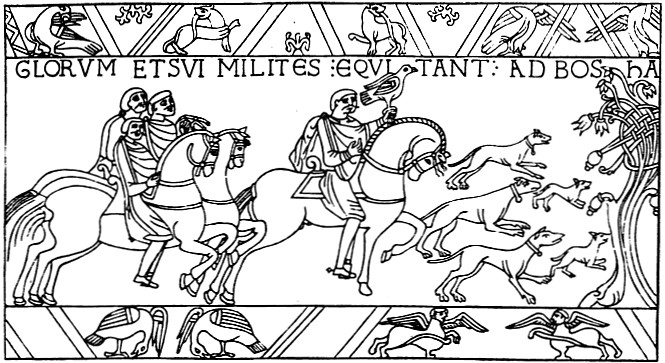

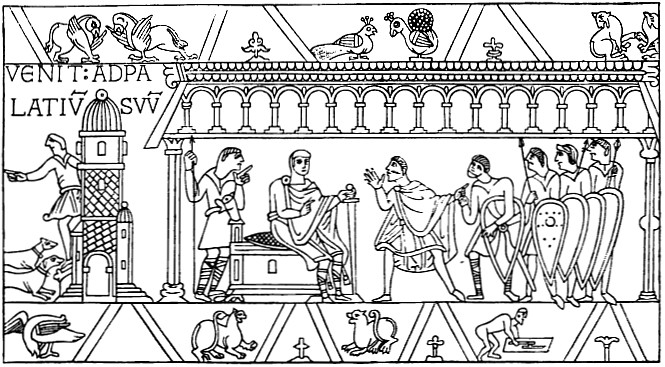

William entertained Harold many days in great honour, as was his due. He took him to many rich tournaments, arrayed him nobly, gave him horses and arms, and led him with him into Britanny—I am not certain whether three or four times—when he had to fight with the Bretons123. And in the meantime he bespoke Harold so fairly, that he agreed to deliver up England to him, as soon as king Edward should die; and he was to have Ele124, one of William's daughters, for his wife if he would; and to swear to all this if required, William also binding himself to those terms.

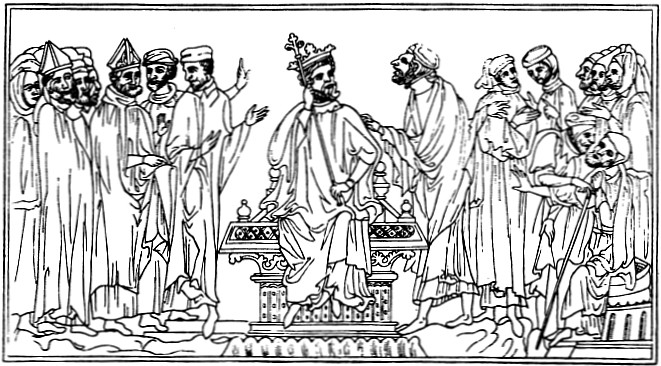

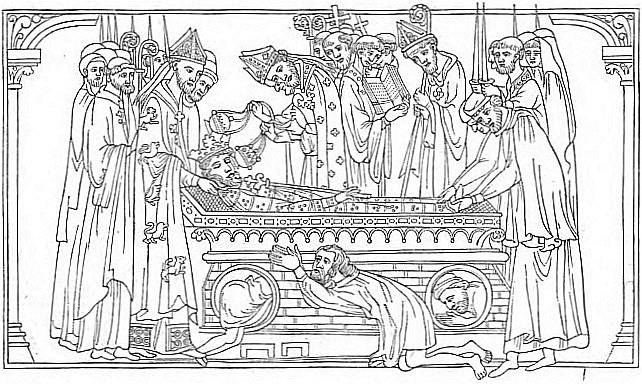

To receive the oath, he caused a parliament to be called. It is commonly said that it was at Bayeux125 that he had his great council assembled. He sent for all the holy bodies thither, and put so many of them together as to fill a whole chest, and then covered them with a pall; but Harold neither saw them, nor knew of their being there; for nought was shewn or told to him about it; and over all was a philactery, the best that he could select; OIL DE BŒF126, I have heard it called. When Harold placed his hand upon it, the hand trembled, and the flesh quivered; but he swore, and promised upon his oath, to take Ele to wife, and to deliver up England to the duke: and thereunto to do all in his power, according to his might and wit, after the death of Edward, if he should live, so help him God and the holy relics there! Many cried "God grant it127!" and when Harold had kissed the saints, and had risen upon his feet, the duke led him up to the chest, and made him stand near it; and took off the chest the pall that had covered it, and shewed Harold upon what holy relics he had sworn; and he was sorely alarmed at the sight.

Then when all was ready for his journey homeward, he took his leave; and William exhorted him to be true to his word, and kissed him in the name of good faith and friendship. And Harold passed freely homeward, and arrived safely in England.

CHAPTER IX.

HOW KING EDWARD DIED, AND HAROLD WAS CROWNED IN HIS STEAD; AND HOW DUKE WILLIAM TOOK COUNSEL AGAINST HIM

The day came that no man can escape, and king Edward drew near to die. He had it much at heart, that William should have his kingdom, if possible; but he was too far off, and it was too long to tarry for him, and Edward could not defer his hour. He lay in heavy sickness, in the illness whereof he was to die; and he was very weak, for death pressed hard upon him128.

Then Harold assembled his kindred, and sent for his friends and other people, and entered into the king's chamber, taking with him whomsoever he pleased. An Englishman began to speak first, as Harold had directed him, and said; "Sire, we sorrow greatly that we are about to lose thee; and we are much alarmed, and fear that great trouble may come upon us: yet we cannot lengthen thy life, nor alter thy fate. Each one must die for himself, and none for another; neither can we cure thee; so that thou canst not escape death; but dust must return to dust. No heir of thine remains who may comfort us after thy death. Thou hast lived long, and art now old, but thou hast had no child, son or daughter; nor hast thou other heir, who may remain instead of thee to protect and guard us, and to become king by lineage. On this account the people weep and cry aloud, and say they are ruined, and that they shall never have peace again if thou failest them. And in this, I trow, they say truly; for without a king they will have no peace, and a king they cannot have, save through thee. Give then thy kingdom in thy lifetime to some one who is strong enough to maintain us in peace. God grant that none other than such may be our king! Wretched is a realm, and little worth, when justice and peace fail; and he who doth not or cannot maintain them, has little right to the kingdom he hath. Well hast thou lived, well hast thou done, and well wilt thou do; thou hast ever served God, and wilt be rewarded of him. Behold the best of thy people, the noblest of thy friends; all are come to beseech thee, and thou must grant their prayer before thou goest hence, or thou wilt not see God. All come to implore thee that Harold may be king of this land. We can give thee no better advice, and no better canst thou do."

As soon as he had named Harold, all the English in the chamber cried out that he said well, and that the king ought to give heed to him. "Sire," they said," if thou dost it not, we shall never in our lives have peace."

Then the king sat up in his bed, and turned his face to the English there, and said, "Seignors, you well know, and have ofttimes heard, that I have given my realm at my death to the duke of Normandy; and as I have given it, so have some among you sworn that it shall go."

But Harold, who stood by, said, "Whatever thou hast heretofore done, sire, consent now that I shall be king, and that your land be mine; I wish for no other title, and want no one to do any thing more for me." "Harold," said the king, "thou shalt have it, but I know full well that it will cost thee thy life. If I know any thing of the duke, and the barons that are with him, and the multitude of people that he can command, none but God can avail to save thee."

Then Harold said that he would stand the hazard, and that if the king would do what he asked, he feared no one, be he Norman or other. So the king turned round and said,—whether of his own free will I know not,—"Let the English make either the duke or Harold king as they please, I consent." Thus he made Harold heir to his kingdom, as William could not have it. A kingdom must have a king; without one, in fact, it would be no kingdom; so he let his barons have their own will.

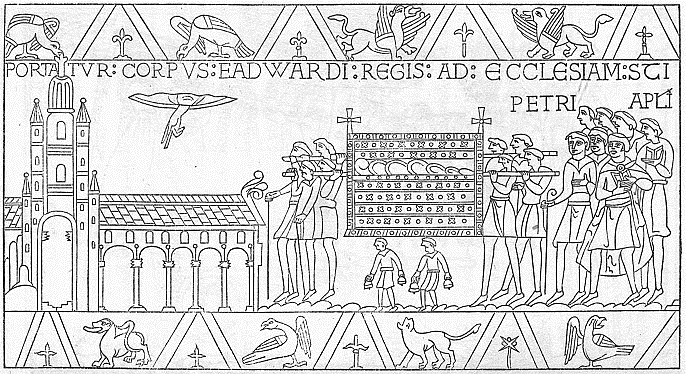

And now he could abide no longer. He died, and the English lamented much over him. His body was greatly honoured, and was buried at Westminster; and the tomb which was made for him was rich, and endureth still. As soon as king Edward was dead, Harold, who was rich and powerful, had himself anointed and crowned, and said nought of it to the duke, but took the homage and fealty of the richest, and best born of the land129.

The duke was in his park at Rouen130. He held in his hand a bow, which he had strung and bent, making it ready for the arrow; and he had given it into the hands of a page, for he was going forth, I believe, to the chace, and had with him many knights and pages131 and esquires, when behold! at the gate appeared a serjeant, who came journeying from England, and went straight to the duke and saluted him, and drew him on one side, and told him privily that king Edward was dead, and that Harold was raised to be king.

When the duke had listened to him, and learnt all the truth, how that Edward was dead, and Harold was made king, he became as a man enraged, and left the craft of the woods. Oft he tied his mantle, and oft he untied it again; and spoke to no man, neither dared any man speak to him. Then he crossed the Seine in his boat, and came to his hall, and entered therein; and sat down at the end of a bench, shifting his place from time to time, covering his face with his mantle, and resting his head against a pillar. Thus he remained long, in deep thought, for no one dared speak to him; but many asked aside, "What ails the duke, why makes he such bad cheer?" Then behold in came his seneschal132, who rode from the park on horseback; and he passed close by the duke, humming a tune as he went along the hall; and many came round him, asking how it came to pass that the duke was in such plight. And he said to them, "Ye will hear news, but press not for it out of season; news will always spread some time or another, and he who gets it not fresh, has it old."

Then the duke raised himself up, and the seneschal said to him, "Sire, sire, why do you conceal the news you have heard? If men hear it not at one time, they will at another; concealment will do you no good, nor will the telling of it do harm. What you keep so close, is by this time known all over the city; for men go through the streets telling, and all know, both great and small, that king Edward is dead, and that Harold is become king in his stead, and possesses the realm."

"That indeed is the cause of my sorrow," said the duke, "but I know no help for it. I sorrow for Edward, and for his death, and for the wrong that Harold has done me. He has wronged me in taking the kingdom that was granted and promised to me, as he himself had sworn."

To these words Fitz Osber, the bold of heart, replied, "Sire, do not vex yourself, but bestir yourself for your redress; that you may be revenged on Harold, who hath been so disloyal to you. If your courage fail not, the land shall not abide with him. Call together all that you can call; cross the sea, and take the kingdom from him. A bold man should begin nothing unless he pursue it to the end; what he begins he should carry through, or abandon it without more ado."

Thus the fame of king Harold's act went through the country. William sent to him often, and reminded him of his oath; and Harold replied injuriously, that he would do nought for him, neither take his daughter, nor yield up the land. Then William sent him his defiance, but Harold always answered that he feared him nought133. The Normans who dwelt in England, who had wives and children there, men whom Edward had invited and endowed with castles and fiefs, Harold chased out of the country, nor would he leave one there; he drove out fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters134.

Harold received the crown at Easter (Christmas – see note – mdh); but it would have been better for him if he had done otherwise, for he brought nought but evil on his heirs, and on all the land. He perjured himself for a kingdom, and that kingdom endured but little space; to him it was a great loss, and it brought all his lineage to sorrow. He refused to take the duke's daughter to wife, he would neither give nor take according to his covenant, and heavily will he suffer for it; he, and all he loves most.

When William found that Harold would do nothing towards performing his covenant, he considered and took counsel, how to cross the sea, and fight him, and by our Lord's leave, take vengeance for his perjury. He pondered much on the wrongs Harold had done him, and on his not deigning even to speak with him before he got himself crowned, and thus robbed him of what Edward had given him, and Harold himself had sworn to observe. If, he said, he could attack and punish him without crossing the sea, he would willingly have done so; but he would rather cross the sea than not revenge himself, and pursue his right. So he determined to go over sea, and take his revenge.