полная версия

полная версияTen Thousand a-Year. Volume 1

The next morning, which proved as fine as the preceding, Mr. Aubrey was detained in-doors with his letters, and one or two other little matters of business in his library, till luncheon time. "What say you, Kate, to a ride round the country?" said he, on taking his seat. Kate was delighted; and forthwith the horses were ordered to be got ready as soon as possible.

"You must not mind a little rough riding, Kate, by the way," said Aubrey; "for we shall have to get over some ugly places!—I'm going to meet Waters at the end of the avenue, about that old sycamore—we must have it down at last."

"Oh no, Charles, no; I thought we had settled that last year!" replied Kate, earnestly.

"Pho! if it had not been for you, Kate, it would have been down two years ago at least. Its hour is come at last; 'tis indeed, so no pouting! It is injuring the other trees; and, besides, it spoils the prospect from the left wing of the house."

"'Tis only Waters that puts all these things into your head, Charles, and I shall let him know my opinion on the subject when I see him! Mamma, haven't you a word to say for the old"–

But Mr. Aubrey, not deeming it discreet to await the new force which was being brought against him, started off to inspect a newly purchased horse, just brought to the stables.

Kate, who really became everything, looked charming in her blue riding-habit and hat, sitting on her horse with infinite ease and grace; in fact, a capital horsewoman. The exercise soon brought a rich bloom upon her cheek; and as she cantered along the road by the side of her brother, no one could have met them without being almost startled at her beauty. Just as they had dropped into an easy walk—

"Charles," said she, observing two horsemen approaching them, "who can these be? Heavens! did you ever see such figures? And how they ride!"

"Why, certainly," replied her brother, smiling, "they look a brace of arrant Cockneys! Ah, ha!—what can they be doing in these parts?"

"Dear me, what puppies!" exclaimed Miss Aubrey, lowering her voice as they neared the persons she spoke of.

"They are certainly a most extraordinary couple! Who can they be?" said Mr. Aubrey, a smile forcing itself into his features. One of the gentlemen thus referred to, was dressed in a light blue surtout, with the tip of a white pocket-handkerchief seen peeping out of a pocket in the front of it. His hat, with scarce any brim to it, was stuck aslant on the top of a bushy head of queer-colored hair. His shirt-collar was turned down completely over his stock, displaying a great quantity of dirt-colored hair under his chin; while a pair of mustaches, of the same color, were sprouting upon his upper lip, and a perpendicular tuft depended from his under lip. A quizzing-glass was stuck in his right eye, and in his hand he carried a whip with a shining silver head. The other was almost equally distinguished by the elegance of his appearance. He had a glossy hat, a purple-colored velvet waistcoat, two pins connected by little chains in his stock, a bottle-green surtout, sky-blue trousers, and a most splendid riding-whip. In short, who should these be but our old friends, Messrs. Titmouse and Snap? Whoever they might be—and whatever their other accomplishments, it was plain that they were perfect novices on horseback; and their horses had every appearance of having been much fretted and worried by their riders. To the surprise of Mr. Aubrey and his sister, these two personages attempted to rein in as they neared, and evidently intended to speak to them.

"Pray—a—sir, will you, sir, tell us," commenced Titmouse, with a desperate attempt to appear at his ease, as he tried to make his horse stand still for a moment—"isn't there a place called—called"—here his horse, whose sides were constantly being galled by the spurs of its unconscious rider, began to back a little; then to go on one side, and, in Titmouse's fright, his glass dropped from his eye, and he seized hold of the pommel. Nevertheless, to show the lady how completely he was at his ease all the while, he levelled a great many oaths and curses at the unfortunate eyes and soul of his wayward brute; who, however, not in the least moved by them, but infinitely disliking the spurs of its rider and the twisting round of its mouth by the reins, seemed more and more inclined for mischief, and backed close up to the edge of the ditch.

"I'm afraid, sir," said Mr. Aubrey, kindly and very earnestly, "you are not much accustomed to riding. Will you permit me"–

"Oh, yes—ye—ye—s, sir, I am though,—uncommon—whee-o-uy! whuoy!"—(then a fresh volley of oaths.) "Oh, dear, 'pon my soul—ho! my eyes!—what—what is he going to do! Snap! Snap!"—'T was, however, quite in vain to call on that gentleman for assistance; for he had grown as pale as death, on finding that his own brute seemed strongly disposed to follow the infernal example (or rather, as it were, the converse of it) of the other, and was particularly inclined to rear up on its hind-legs. The very first motion of that sort brought Snap's heart (not large enough, perhaps, to choke him) into his mouth. Titmouse's beast, in the mean while, suddenly wheeled round; and throwing its hind feet into the air, sent its terrified rider flying head over heels into the very middle of the hedge, from which he dropped into the soft wet ditch on the road-side. Both Mr. Aubrey and his groom immediately dismounted, and secured the horse, who, having got rid of its ridiculous rider, stood perfectly quiet. Titmouse proved to be more frightened than hurt. His hat was crushed flat on his head, and half the left side of his face covered with mud—as, indeed, were his clothes all the way down. The groom (almost splitting with laughter) helped him on his horse again; and as Mr. and Miss Aubrey were setting off—"I think, sir," said the former, politely, "you were inquiring for some place?"

"Yes, sir," quoth Snap. "Isn't there a place called Ya—Yat—Yat—(be quiet, you brute!)—Yatton about here?"

"Yes, sir—straight on," replied Mr. Aubrey. Miss Aubrey hastily threw her veil over her face, to conceal her laughter, urging on her horse; and she and her brother were soon out of sight of the strangers.

"I say, Snap," quoth Titmouse, when he had in a measure cleansed himself, and they had both got a little composed, "see that lovely gal?"

"Fine gal—devilish fine!" replied Snap.

"I'm blessed if I don't think—'pon my life, I believe we've met before!"

"Didn't seem to know you though!"– quoth Snap, somewhat dryly.

"Ah! you don't know—How uncommon infernal unfortunate to happen just at the moment when"– Titmouse became silent; for all of a sudden he recollected when and where, and under what circumstances he had seen Miss Aubrey before, and which his vanity would not allow of his telling Snap. The fact was, that she had once accompanied her sister-in-law to Messrs. Tag-rag and Company's, to purchase some small matter of mercery. Titmouse had served them; and his absurdity of manner and personal appearance had provoked a smile, which Titmouse a little misconstrued; for when, a Sunday or two afterwards, he met her in the Park, the little fool actually had the presumption to nod to her—she having not the slightest notion who the little wretch might be—and of course not having, on the present occasion, the least recollection of him. The reader will recollect that this incident made a deep impression on the mind of Mr. Titmouse.

The coincidence was really not a little singular—but to return to Mr. Aubrey and his sister. After riding a mile or two farther up the road, they leaped over a very low mound or fence, which formed the extreme boundary of that part of the estate, and having passed through a couple of fields, they entered the eastern extremity of that fine avenue of elms, at the higher end of which stood Kate's favorite tree, and also Waters and his under-bailiff—who looked to her like a couple of executioners, only awaiting the fiat of her brother. The sun shone brightly upon the doomed sycamore—"the axe was laid at its root." As they rode up the avenue, Kate begged very hard for mercy; but for once her brother seemed obdurate—the tree, he said, must come down—'t was all nonsense to think of leaving it standing any longer!—

"Remember, Charles," said she, passionately, as they drew up, "how we've all of us romped and sported under it! Poor papa also"–

"See, Kate, how rotten it is," said her brother; and riding close to it, with his whip he snapped off two or three of its feeble silvery-gray branches—"it's high time for it to come down."

"It fills the grass all round with little branches, sir, whenever there's the least breath of wind," said Waters.

"It won't hardly hold a crow's weight on the topmost branches, sir," added Dickons, the under-bailiff, very modestly.

"Had it any leaves last summer?" inquired Mr. Aubrey.

"I don't think, sir," replied Waters, "it had a hundred all over it!"

"Really, Kate," said her brother, "'t is such a melancholy, unsightly object, when seen from any part of the Hall"—turning round on his horse to look at the rear of the Hall, which was at about two hundred yards' distance. "It looks such an old withered thing among the fresh green trees around it—'t is quite a painful contrast." Kate had gently urged on her horse while her brother was speaking, till she was close beside him. "Charles," said she, in a low whisper, "does not it remind you a little of poor old mamma, with her gray hairs, among her children and grandchildren? She is not out of place among us—is she?" Her eyes filled with tears. So did her brother's.

"Dearest Kate," said he, with emotion, affectionately grasping her little hand, "you have triumphed! The old tree shall never be cut down in my time! Waters, let the tree stand; and if anything is to be done to it—let the greatest possible care be taken of it." Miss Aubrey turned her head aside to conceal her emotion. Had they been alone, she would have flung her arms round her brother's neck.

"If I were to speak my mind, sir," said the compliant Waters, seeing the turn things were taking, "I should say, with our young lady, the old tree's quite a kind of ornament in this here situation, and (as one might say) it sets off the rest." [It was he who had been worrying Mr. Aubrey for these last three years to have it cut down!]

"Well," replied Mr. Aubrey, "however that may be, let me hear no more of cutting it down—Ah! what does old Jolter want here?" said he, observing an old tenant of that name, almost bent double with age, hobbling towards them. He was wrapped up in a coarse thick blue coat; his hair was long and white; his eyes dim and glassy with age.

"I don't know, sir—I'll go and see," said Waters.

"What's the matter, Jolter?" he inquired, stepping forward to meet him.

"Nothing much, sir," replied the old man, feebly, and panting, taking off his hat, and bowing very low towards Mr. and Miss Aubrey.

"Put your hat on, my old friend," said Mr. Aubrey, kindly.

"I only come to bring you this bit of paper, sir, if you please," said the old man, addressing Waters. "You said, a while ago, as how I was always to bring you papers that were left with me; and this"—taking one out of his pocket—"was left with me only about an hour ago. It's seemingly a lawyer's paper, and was left by an uncommon gay young chap. He asked me my name, and then he looked at the paper, and read it all over to me, but I couldn't make anything of it."

"What is it?" inquired Mr. Aubrey, as Waters cast his eye over a sheet of paper, partly printed and partly written.

"Why, it seems the old story, sir—that slip of waste land, sir. Mr. Tomkins is at it again, sir."

"Well, if he chooses to spend his money in that way, I can't help it," said Mr. Aubrey, with a smile. "Let me look at the paper." He did so. "Yes, it seems the same kind of thing as before. Well," handing it back, "send it to Mr. Parkinson, and tell him to look to it; and, at all events, take care that poor old Jolter comes to no trouble by the business. How's the old wife, Jacob?"

"She's dreadful bad with rheumatis, sir; but the stuff that Madam sends her does her a woundy deal of good, sir, in her inside."

"Well, we must try if we can't send you some more; and, harkee, if the goodwife doesn't get better soon, send us up word to the Hall, and we'll have the doctor call on her. Now, Kate, let us away homeward." And they were soon out of sight.

I do not intend to deal so unceremoniously or summarily as Mr. Aubrey did, with the document which had been brought to his notice by Jolter, then handed over to Waters, and by him, according to orders, transmitted the next day to Mr. Parkinson, Mr. Aubrey's attorney. It was what is called a "Declaration in Ejectment;" touching which, in order to throw a ray or two of light upon a document which will make no small figure in this history, I shall try to give the reader a little information on the point; and hope that a little attention to what now follows, will be repaid in due time. Here beginneth a little lecture on law.

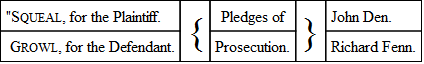

If Jones claim a debt, or goods, or damages, from Smith, one should think that, if he went to law, the action would be entitled "Jones versus Smith;" and so it is. But behold, if it be land which is claimed by Jones from Smith, the style and name of the cause stand thus:—"Doe, on the demise of Jones, versus Roe." Instead, therefore, of Jones and Smith fighting out the matter in their own proper names, they set up a couple of puppets, (called "John Doe" and "Richard Roe,") who fall upon one another in a very quaint fashion, after the manner of Punch and Judy. John Doe pretends to be the real plaintiff, and Richard Roe the real defendant. John Doe says that the land which Richard Roe has, is his, (the said John Doe's,) because Jones (the real plaintiff) gave him a lease of it; and Jones is then called "the lessor of the plaintiff." John Doe further says that one Richard Roe, (who calls himself by the very significant and expressive name of a "Casual Ejector,") came and turned him out, and so John Doe brings his action against Richard Roe. 'Tis a fact, that whenever land is sought to be recovered in England, this anomalous and farcical proceeding must be adopted.[15] It is the duty of the real plaintiff (Jones) to serve on the real defendant (Smith) a copy of the queer document which I shall proceed to lay before the reader; and also to append to it an affectionate note, intimating the serious consequences which will ensue upon inattention or contumacy. The "Declaration," then, which had been served upon old Jolter, was in the words, letters, and figures following—that is to say:—

"In the King's Bench.

"Michaelmas Term, the– of King–."Yorkshire, to-wit—Richard Roe was attached to answer John Doe of a plea wherefore the said Richard Roe, with force and arms, &c., entered into two messuages, two dwelling-houses, two cottages, two stables, two out-houses, two yards, two gardens, two orchards, twenty acres of land covered with water, twenty acres of arable land, twenty acres of pasture land, and twenty acres of other land, with the appurtenances, situated in Yatton, in the county of York, which Tittlebat Titmouse, Esquire, had demised to the said John Doe for a term which is not yet expired, and ejected him from his said farm, and other wrongs to the said John Doe there did, to the great damage of the said John Doe, and against the peace of our Lord the King, &c.; and Thereupon the said John Doe, by Oily Gammon, his attorney, complains,—

"That whereas the said Tittlebat Titmouse, on the —th day of August, in the year of our Lord 18—, at Yatton aforesaid, in the county aforesaid, had demised the same tenements, with the appurtenances, to the said John Doe, to have and to hold the same to the said John Doe and his assigns thenceforth, for and during, and unto the full end and term of twenty years thence next ensuing, and fully to be completed and ended: By virtue of which said demise, the said John Doe entered into the said tenements, with the appurtenances, and became and was thereof possessed for the said term, so to him thereof granted as aforesaid. And the said John Doe being so thereof possessed, the said Richard Roe afterwards, to-wit, on the day and year aforesaid, at the parish aforesaid, in the county aforesaid, with force and arms, that is to say with swords, staves, and knives, &c., entered into the said tenements, with the appurtenances, which the said Tittlebat Titmouse had demised to the said John Doe in manner and for the term aforesaid, which is not yet expired, and ejected the said John Doe out of his said farm; and other wrongs to the said John Doe then and there did, to the great damage of the said John Doe, and against the peace of our said Lord the now King. Wherefore the said John Doe saith that he is injured, and hath sustained damage to the value of £50, and therefore he brings his suit, &c.

"Mr. Jacob Jolter,

"I am informed that you are in possession of, or claim title to, the premises in this Declaration of Ejectment mentioned, or to some part thereof: And I, being sued in this action as a casual ejector only, and having no claim or title to the same, do advise you to appear, next Hilary term, in His Majesty's Court of King's Bench at Westminster, by some attorney of that Court; and then and there, by a rule to be made of the same Court, to cause yourself to be made defendant in my stead; otherwise, I shall suffer judgment to be entered against me by default, and you will be turned out of possession.

"Your loving friend,

Richard Roe."Dated this 8th day of December 18—."[16]

You may regard the above document in the light of a deadly and destructive missile, thrown by an unperceived enemy into a peaceful citadel; attracting no particular notice from the innocent unsuspecting inhabitants—among whom, nevertheless, it presently explodes, and all is terror, death, and ruin.

Mr. Parkinson, Mr. Aubrey's solicitor, who resided at Grilston, the post-town nearest to Yatton, from which it was distant about six or seven miles, was sitting on the evening of Tuesday the 28th December 18—, in his office, nearly finishing a letter to his London agents, Messrs. Runnington and Company—one of the most eminent firms in the profession—and which he was desirous of despatching by that night's mail. Among other papers which have come into my hands in connection with this history, I have happened to light on the letter which he was writing; and as it is not long, and affords a specimen of the way in which business is carried on between town and country attorneys and solicitors, here followeth a copy of it:—

"Grilston, 28th Dec. 18—."Dear Sirs,

"Re Middleton"Have you got the marriage-settlements between these parties ready? If so, please send them as soon as possible; for both the lady's and gentleman's friends are (as usual in such cases) very pressing for them.

"Puddinghead v. Quickwit"Plaintiff bought a horse of defendant in November last, 'warranted sound,' and paid for it on the spot £64. A week afterwards, his attention was accidentally drawn to the animal's head; and to his infinite surprise, he discovered that the left eye was a glass eye, so closely resembling the other in color, that the difference could not be discovered except on a very close examination. I have seen it myself, and it is indeed wonderfully well done. My countrymen are certainly pretty sharp hands in such matters—but this beats everything I ever heard of. Surely this is a breach of the warranty? Or is it to be considered a patent defect, which would not be within the warranty?[17]—Please take pleader's opinion, and particularly as to whether the horse could be brought into court to be viewed by the court and jury, which would have a great effect. If your pleader thinks the action will lie, let him draw declaration, venue—Lancashire (for my client would have no chance with a Yorkshire jury,) if you think the venue is transitory, and that defendant would not be successful on a motion to change it. Qu.—Is the man who sold the horse to defendant a competent[18] witness for the plaintiff, to prove that, when he sold it to defendant, it had but one eye, and that on this account the horse was sold for less?

"Mule v. Stott"I cannot get these parties to come to an amicable settlement. You may remember, from the two former actions, that it is for damages on account of two geese of defendant having been found trespassing on a few yards of a field belonging to the plaintiff. Defendant now contends that he is entitled to common, pour cause de vicinage. Qu.—Can this be shown under Not Guilty, or must it be pleaded specially?—About two years ago, by the way, a pig belonging to plaintiff got into defendant's flower-garden, and did at least £3 worth of damage—Can this be in any way set off against the present action? There is no hope of avoiding a third trial, as the parties are now more exasperated against each other than ever, and the expense (as at least fifteen witnesses will be called on each side) will amount to upwards of £250. You had better retain Mr. Cacklegander.

"Re Lords Oldacre and De la Zouch"Are the deeds herein engrossed? As it is a matter of magnitude, and the foundation of extensive and permanent family arrangements, pray let the greatest care be taken to secure accuracy. Please take special care of the stamps"–

Thus far had the worthy writer proceeded with his letter, when Waters made his appearance, delivering to him the declaration in ejectment which had been served upon old Jolter, and also the instructions concerning it which had been given by Mr. Aubrey. After Mr. Parkinson had asked particularly concerning Mr. Aubrey's health, and what had brought him so suddenly to Yatton, he cast his eye hastily over the "Declaration"—and at once and contemptuously came to the same conclusion concerning it which had been arrived at by Waters and Mr. Aubrey, viz. that it was another little arrow out of the quiver of the litigious Mr. Tomkins. As soon as Waters had left, Mr. Parkinson thus proceeded to conclude his letter:—

"Doe dem. Titmouse v. Roe.

"I enclose you Declaration herein, served yesterday. No doubt it is the disputed slip of waste land adjoining the cottage of old Jacob Jolter, a tenant of Mr. Aubrey of Yatton, that is sought to be recovered. I am quite sick of this petty annoyance, as also is Mr. Aubrey, who is now down here. Please call on Messrs. Quirk, Gammon, and Snap, of Saffron Hill, and settle the matter finally, on the best terms you can; it being Mr. Aubrey's wish that old Jolter (who is very feeble and timid) should suffer no inconvenience. I observe a new lessor of the plaintiff, with a very singular name. I suppose it is the name of some prior holder of the acre or two of property at present held by Mr. Tomkins.

"Hoping soon to hear from you, (particularly about the marriage-settlement,) I am,

"Dear Sirs,

"(With all the compliments of the season,)

"Yours truly,

"James Parkinson."Messrs. Runnington & Co.

"P. S.—The oysters and codfish came to hand in excellent order, for which please accept my best thanks.

"I shall remit you in a day or two £100 on account."

This letter, lying among some twenty or thirty similar ones on Mr. Runnington's table, on the morning of its arrival in town, was opened in its turn; and then, in like manner, with most of the others, handed over to the managing clerk, in order that he might inquire into and report upon the state of the various matters of business referred to. As to the last item (Doe dem. Titmouse v. Roe) in Mr. Parkinson's letter, there seemed no particular reason for hurrying; so two or three days had elapsed before Mr. Runnington, having some little casual business to transact with Messrs. Quirk, Gammon, and Snap, bethought himself of looking at his Diary, to see if there were not something else that he had to do with that very sharp "house." Putting, therefore, the Declaration in Doe d. Titmouse v. Roe into his pocket, it was not long before he was to be seen at the office in Saffron Hill—and in the very room in it which had been the scene of several memorable interviews between Mr. Tittlebat Titmouse and Messrs. Quirk, Gammon, and Snap. I shall not detail what transpired on that occasion between Mr. Runnington, and Messrs. Quirk and Gammon, with whom he was closeted for nearly an hour. On quitting the office his cheek was flushed, and his manner somewhat excited. After walking a little way in a moody manner and with slow step, he suddenly jumped into a hackney-coach, and within a quarter of an hour's time had secured an inside place in the Tally-ho coach, which started for York at two o'clock that afternoon—much doubting within himself, the while, whether he ought not to have set off at once in a post-chaise and four. He then made one or two calls in the Temple; and, hurrying home to the office, made hasty arrangements for his sudden journey into Yorkshire. He was a calm and experienced man—in fact, a first-rate man of business; and you may be assured that this rapid and decisive movement of his had been the result of some very startling disclosure made to him by Messrs. Quirk and Gammon.